Man unable to “see” numbers after suffering rare brain disease

Schuberta et al.

- When a man who was diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease corticobasal syndrome looked at the numbers 2 through 9, he saw unintelligible squiggly lines.

- The disability appears to be a peculiar type of metamorphopsia, a visual defect that causes linear objects, like the lines on a grid, to look curvy or rounded.

- The study has some interesting implications on theories of consciousness.

Someone writes the number 8 on a piece of paper. You look at it, see a shape, but you can’t identify what number it is, or whether it’s a number at all. The markings just look like “spaghetti.”

It sounds strange, but that’s exactly what happened to a man who suffers from a rare neurodegenerative disease called corticobasal syndrome, and now can’t recognize the digits 2 through 9. This disease, caused by damage to the cortex and basal ganglia, often leads to memory problems and difficulty moving, but the inability to identify numbers seems to be a very rare symptom.

In a 2020 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team of researchers describe how the unique disability sheds light on how the brain processes visual awareness.

The inability to identify numbers posed an immediate puzzle for researchers. If the man (named “RFS” in the paper) can read letters and words, but not numbers, that means his brain must be identifying the numbers — and then selectively discriminating against them.

The disability appears to be a peculiar type of metamorphopsia, a visual defect that causes linear objects, like the lines on a grid, to look curvy or rounded.

“When he looks at a digit, his brain has to ‘see’ that it is a digit before he can not see it — it’s a real paradox,” said senior author and cognitive scientist, Michael McCloskey, in a news release. “In this paper what we did was to try to investigate what processing went on outside his awareness.”

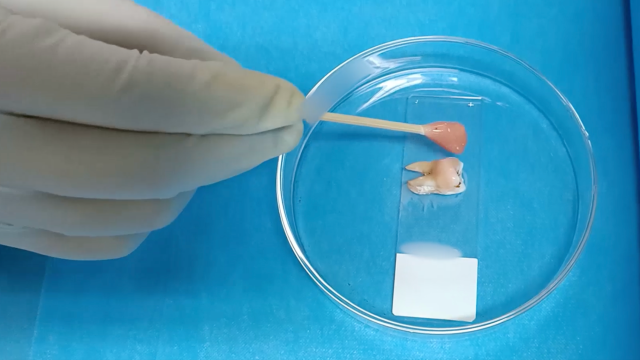

RFS was also unable to see words or drawings placed inside or near the numbers 2 through 9. For example, he wasn’t able to see an image of a violin drawn inside the number 3. But when the violin was placed far enough away from the number, he was able to see it.

In an electroencephalography (EEG) experiment, the team found that even though RFS said he didn’t see images placed near numbers, his brain was registering that words were there.

“He was completely unaware that a word was there, yet his brain was not only detecting the presence of a word, but identifying which particular word it was, such as ‘tuba’,” Harvard University cognitive scientist Teresa Schubert said in a press release.

Is it possible that RFS’ disability can be explained by a psychological issue?

“Given the rare form of RFS’ metamorphopsia, how can we be sure that his deficit is genuine? With any unusual deficit, there is the possibility that the underlying dysfunction is psychiatric, psychogenic, or ‘functional’, rather than an impairment of basic perceptual/cognitive processes,” the team wrote in the paper.

“We believe this unlikely in the present case for multiple reasons … At the time of our study RFS was seeing a psychiatrist for help in adjusting to his condition, and the psychiatrist had no suspicion that any of his perceptual, cognitive, or physical symptoms reflected a functional disorder. In addition, RFS’ performance in two-choice discrimination was not below chance, as is often found in cases of malingered deficits.”

The research has some interesting implications for theories of consciousness. As the paper states, some theories propose that humans are able to perform “certain types of complex cognitive processes” because our consciousness interacts with deeper-level processes in the brain. But the results suggest consciousness may play less of a role, because RFS seems to be “computing complex, task-sensitive representations in the absence of awareness.”

This article was originally published on Big Think in June 2020. It was updated in August 2022.