Treasures of Egypt: stunning photos from National Geographic’s archive

- The 2022 book Treasures of Egypt: A Legacy in Photographs From the Pyramids to Cleopatra features stunning photos of ancient Egyptian monuments and artifacts.

- This excerpt of the book offers a glimpse of those images, which come from National Geographic’s archive.

- As time moves on, our knowledge of ancient Egypt changes—as does the way in which we gain it.

The year 2022 marks two key anniversaries in the world of Egyptology: A century ago, on November 4, 1922, the crew working for archaeologist Howard Carter in the Valley of the Kings uncovered the top step of the stairway that led to the tomb of King Tutankhamun. More than 5,000 artifacts filled four modest underground chambers. Meant to be accessible to Tut in the next life, their sheer quantity and stunning craftsmanship have made the young king a legend.

A century before that, in September 1822, an equally important milestone was announced. French linguist Jean-François Champollion had deciphered the ancient hieroglyphic code, unlocking the secrets of ancient Egyptian texts.

The rules that governed the script had been lost for many centuries; until Champollion, explorers and scholars had been unable to make much sense of the signs that covered temples and tombs, soaring stone obelisks, and delicate sheets of papyrus.

“Hieroglyphic writing is a complex system, a script all at once figurative, symbolic, and phonetic, in one and the same text, in one and the same sentence—and, I might even venture, in one and the same word,” Champollion later explained.

For starters, a hieroglyphic sign can represent exactly what it looks like. A bull is a bull, for example. But that same sign can also represent the idea of a herd of cattle. And it can stand for the sound “ka” in a compound word, in the same way bull is used to form the word bullfinch. Context is everything in figuring out exactly what an ancient scribe meant to say.

Cracking the code opened a wide new window into ancient Egyptian lives. Suddenly, people from the past were communicating in their own words to modern readers. Kings bragged of conquests and made their commands known. Well-connected officials were buried with detailed instructions for how to get to the afterworld. A farmer named Khun-Anup, nicknamed the Eloquent Peasant, pleaded for justice after a landowner stole his donkey and the goods it was carrying.

As experts have pieced together the details of Egypt’s 3,000-year pharaonic history—the dynasties that rose and fell, the battles won and lost—a fascinating picture of this ancient civilization has come into view. We now know the names of kings, their queens, and their children. Of courtiers and priests. Of cities and towns. Of the many gods and goddesses who oversaw every aspect of Egyptian life. We see the clever inventions—the plow, a calendar, majestic pyramids, and stationery made from the fibers of papyrus plants, the origin of the English word paper. Stretching across time and space, the story grows with every new discovery. Those of us hooked on this great, sweeping saga eagerly await the start of the dig season around October every year—and the news of what artifacts archaeologists are turning up.

Here are just a few of the extraordinary sites and artifacts that archaeologists have investigated over the years, and are now featured in the new National Geographic book Treasures of Egypt:

In early 1939, French archaeologist Pierre Montet made one of the greatest discoveries in Egyptology: a royal burial complex that included the intact tombs of three ancient kings. Montet was working at the site of Tanis, the home base of kings in the 21st and 22nd dynasties (about 1075 to 715 B.C). By then, the country’s power had diminished greatly, and the country was divided, with kings controlling the north and religious officials holding court in the south in Waset (modern Luxor). Judging from what Montet found, though, the royals were still fabulously wealthy. In the tomb of King Psusennes I, for example, this gold-trimmed coffin of silver held the king’s remains. A mask of gold covered his head and shoulders, and gold sandals enveloped his feet. In death a king became a deity, so it was fitting for his mummy to wear gold, believed to be the skin of the gods. Sadly, Montet’s discovery never got the recognition it deserved. World War II soon dominated the news, and people had little interest in archaeology, no matter how big a treasure it might have unearthed.

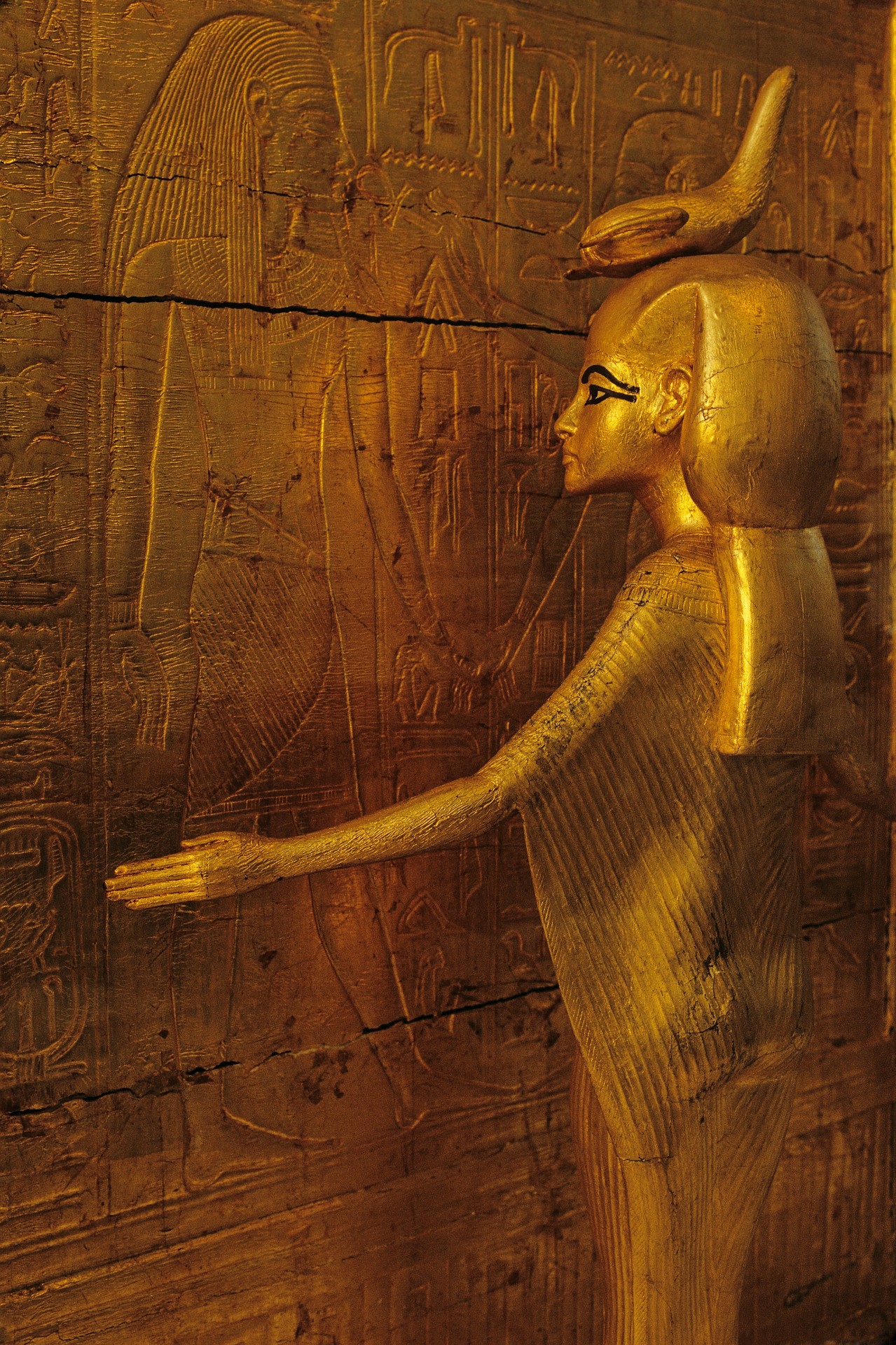

Spreading her arms in protection, a gilded wooden statue of the goddess Selket guards a shrine from King Tutankhamun’s tomb. On her head is a scorpion, her identifying feature. Inside the shrine stood a calcite chest containing the jars that held the king’s viscera.

Yuya and Tuyu, the father- and mother-in-law of King Amenhotep III (1390-1353 B.C.), were laid to rest wearing masks made of linen and plaster. At the time of burial, a dark, gauzy veil was draped over Tuyu’s mask. Parts of it are now stuck to the gilded surface, as seen in this photo.

The couple seems to have benefited from their royal connections even after death. Wonderfully skilled embalmers prepared their remains for the afterlife. Their mummies are still surprisingly well preserved, some 3,400 years after their burial in the Valley of the Kings.

The teenage King Tutankhamun was laid to rest in about 1322 B.C. with unimaginable wealth. His mummified remains were interred in this solid gold coffin weighing more than 243 pounds (110 kg). Inlaid semiprecious stones and glass add details.

The glory of King Ramses II endures in stone at his Abu Simbel temple. By the time of his death in about 1213 B.C., he had come to embody imperial Egypt so strongly that nine later kings adopted his name.

In the 1960s, one of the greatest engineering feats in the history of cultural heritage preservation took place here. As the Aswan High Dam was built to tame the wild annual flooding of the Nile, this temple was disassembled and moved to higher ground, away from the impending waters of Lake Nasser.

In her spectacular tomb near Luxor, Nefertari, the principal wife of Ramses II, wears a headdress in the shape of the protective vulture goddess, Nekhbet. The same artisans who created royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings must have prepared Nefertari’s final resting place, carving rock chambers, plastering walls, and painting every available surface.

As time moves on, our knowledge of ancient Egypt changes—as does the way in which we gain it. Gone are wealthy patrons like Lord Carnarvon, who sponsored the search for King Tut’s tomb over a period of six years. Today, far fewer Egyptian digs are run by foreigners, who once had a virtual monopoly on the thrill of discovery. Egypt is training its own specialists, who increasingly are the ones making the newsworthy finds.

Change is afoot in museums, too. One artifact after another has been leaving the antiquated galleries of the beloved Egyptian Museum, near Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo, for state-of-the-art venues elsewhere. Many items have moved to the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), a spacious, billion-dollar facility of galleries, conservation labs, and conference halls on a grand plaza full of palm trees in sight of the Giza pyramids.

However much change rocks our world, though, there are always some steadying certainties. With almost every shovel of sand shifted in Egypt, another artifact comes to light. These precious traces of the past are reminders of the creativity, inventiveness, and resilience that carried the ancient Egyptians through good times and bad for millennia. These same qualities will continue to serve us all for as long as the human mind produces new ideas in flashes of brilliance.