What role does beauty play in evolution? How does Darwin’s idea of natural selection apply to how we choose mates? Richard O. Prum, professor of Ornithology at Yale University, explains that to truly understand the answers, we need to divorce evolutionary biology from eugenic ideas, which were there from the science’s early days, and get back to the original theories by Darwin.

Richard Prum: A fundamental question in evolutionary biology is the evolution of ornament, especially sexual ornament.

And one way to look at that—how that evolves—is to ask, “Why are certain traits preferred?” The peacock’s tail, or the song of a wood thrush?

In The Origin of Species Charles Darwin proposed that organisms evolved by natural selection to become more and more adapted to their environment.

In proposing this mechanism Darwin articulated the concept of “fitness,” which was an aspect of the individual that allowed it to further its own survival or fecundity. It was like physical fitness: it was something the individual could do in order to further its survival.

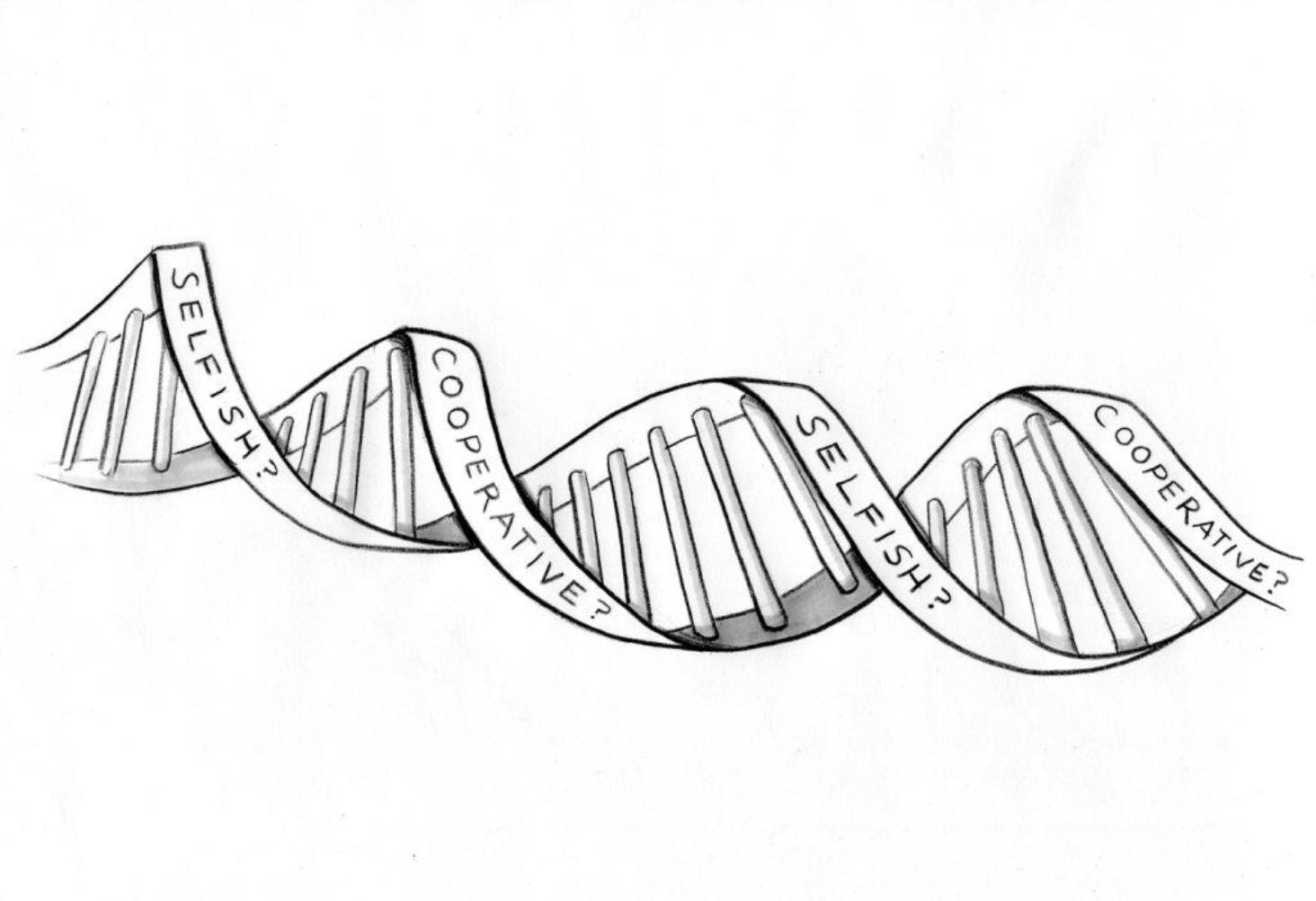

However, later during the early 20th century with the development of modern population genetics, the idea of fitness, the concept of fitness was redefined in an abstract, mathematical way to mean “one’s relative contribution of one’s genes to subsequent populations.”

In this case fitness incorporated both survival and fecundity AND a differential reproductive success—or natural selection AND sexual selection.

This is okay, except that the new, revised concept of fitness kept its romantic association with the idea of adaptation by natural selection, even though it was being applied to both survival and mate choice, which Darwin saw as essentially an aesthetic process.

So what that means is in the early 20th century evolutionary biology and selection became synonymous with natural selection.

This had a number of problems, which, for example, it built right into the machinery of evolutionary biology the idea that mate choice is ALWAYS adaptive, or is (or should be) about adaptation.

100 percent of evolutionary biologists from about 1890 to 1938 were either ardent eugenicists or happy fellow travelers—Full stop.

And that unfortunate past is really part of our history as a discipline. And I think evolutionary biology has a special responsibility to scrutinize the intellectual developments during that period in the way in which those concepts influence the way we think about evolution today.

Animals have an opportunity for sensory perception, cognitive evaluation, and choice, and based on their choices certain kinds of ornament will evolve.

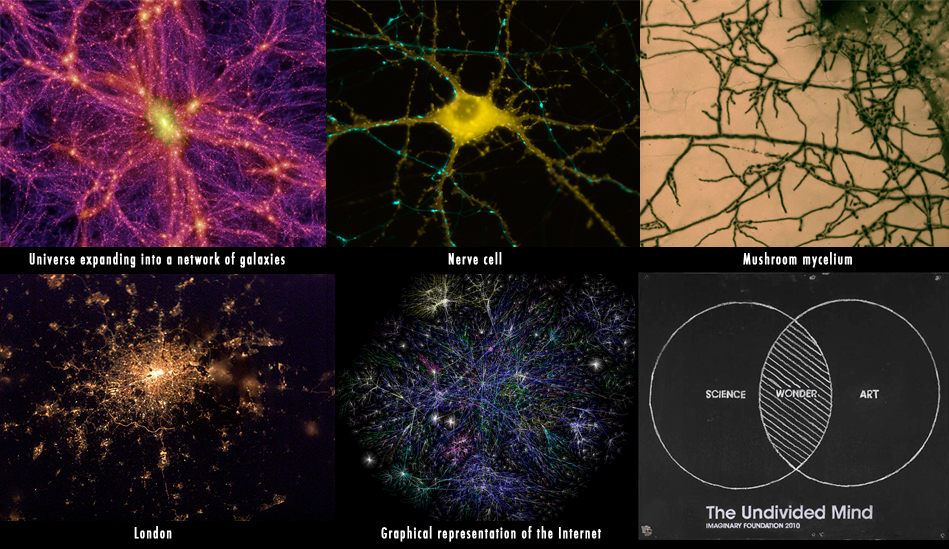

According to the beauty happens theory, beauty evolves merely because it’s preferred. And what that means is that in a population mate choice will create some norm, some standard that is preferred within the population. But also that standard is unstable over time; it can change.

Now, this theory “Beauty Happens” goes back to Charles Darwin, who proposed after The Origin of Species an alternative or new theory for the evolution of ornament through mate choice or sexual selection.

When Darwin proposed that mate choice was a force in evolution—back in the Victorian era—the idea was a big loser among his colleagues. They were very skeptical that animals could be even capable of choice, let alone the kind of aesthetic judgments that Darwin proposed.

Under the Wallacian view, all beauty is merely another kind of practical utility. That beauty, like the peacock’s tail, is preferred because it indicates something about that individual: either that he has good genes, or a good diet, or no sexually transmitted diseases—all sorts of things that mates need to know. The challenge, of course, is to try to figure out what’s actually happening in nature.

Modern evolutionary biologists are quite comfortable with the idea that animals are making choices, yet they are still by and large confident that the kinds of choices that animals make will ALWAYS be controlled by or determined by natural selection, that is, that mate choice will ultimately lead to the evolution of adaptive—or “honest”—ornaments.

This flattening or oversimplification of the Darwinian worldview directly contributed to the eugenic history of evolutionary biology. That is, during the late 19th and early 20th century, 100 percent of evolutionary biologists believed that human diversity had evolved as a result of adaptation to diversity of environments—and this meant that human populations, ethnic groups and races were actually adapted to different environments in a “hierarchy of quality”.

This of course was—this eugenic theory actually failed to be supported and has been scientifically rejected, and yet aspects of the “logic” of eugenics were built into the early or fundamental concepts of modern evolutionary biology through the concept of fitness.

So, how do we proceed forward? I think the best way is to define natural selection and sexual selection as distinct mechanisms, sometimes interacting.

This is a return to the Darwinian structure of evolutionary biology, and I think it’s one that actually will inoculate evolutionary biology from its eugenic roots by essentially uncoupling mate choice from the definition of adaptation.

I think of this like a spinning top, mate choice creates the forces that allows the top to spin and stand on its own in one place, but over time with small disruptions the top can skitter from one place or one direction or another.

So what that means is as species form they tend to evolve new and different varieties of beauty, each more complex than the last. Like a spinning top, if you spin it 10,000 times each time it will arrive at a different place. And that’s one way in which I think the beauty happens theory looks a lot like nature itself, where different species all have different ideas about what’s beautiful.