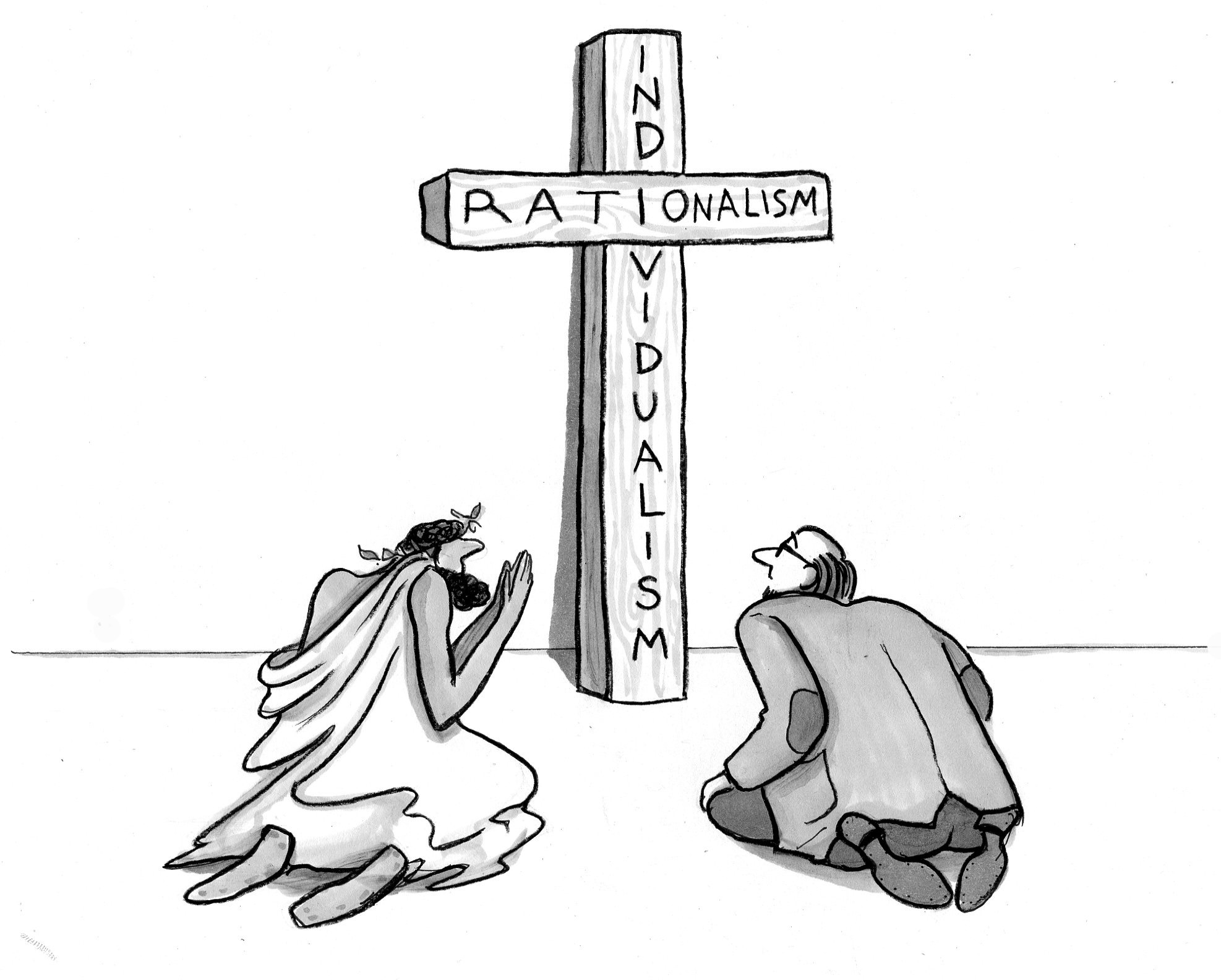

Plato on why debates are stupid and dangerous

- There is a difference between dialectic and debate. When you meet someone with a different view from you, you probably will revert to debate.

- But debate is a kind of sport, with winners and losers. Debates are not about getting closer to the truth, but about who comes out looking the best.

- In Plato’s Greece, the Sophists were professional debaters. Today, we can learn their tricks to see through their hollow arguments.

Few people actually care about the truth. We might say we do, but when it comes down to it, humans are all too susceptible to that age-old foible: pride.

Let’s suppose you’re having drinks with some friends, and you’re having a friendly debate about some controversial topic. You have your opinion, you have your arguments, and you’re up against someone else. Suppose, now, that they deliver a brilliant counterexample and utterly dismantle your position. How do you react? Do you say, “Good point, you might be right,” or do you double down? For Plato, it is a rare person indeed who cares about truth. Most people care only about winning.

There’s a philosophical difference between dialectic and debate. Dialectic is where two people with opposing views discuss which position is the best. Their concern is what’s right, and a dialectic usually resolves with some kind of compromise or synergy that’s an improvement on either position, alone. Debate, though, is a kind of sport. And, as with most sports, there has to be a winner or loser. Like other sports, you can train to become better at debating. You can learn the tricks of the trade to make your opponent look silly or their arguments seem weak.

This is exactly why Plato thought debates were very stupid, dangerous things.

Sophistry and vanity

If you call someone a sophist, you’re calling them a charlatan. A sophist is someone who talks a good talk, can whip up a crowd, and can make a wisecrack at your expense, but has no concern whatsoever with truth. If you call a politician a sophist, you’re saying they care only about getting a vote and lack any notable principles whatsoever. And the reason “sophist” has become such a derogatory term is all because of Plato.

In Plato’s Greece, the Sophists were philosophers of a sort, but they were most concerned with the art of rhetoric and persuasion. They were about debate and not dialectic. Sophists made sometimes oodles of money by teaching others the great art of winning a debate. They would teach aspiring politicians, children from noble families, or anyone with a big enough money pouch how to make your opponent look like an ass. They taught how to get the crowd on your side, and they taught how to look confident while doing it.

Plato argued, then, that Sophists (and the art of debate more generally) were concerned only with popular opinion. They said what they knew would make the crowd happy, and their “principles” always, conspicuously, aligned with whoever was listening. They will flap whichever way the wind blows. For Sophists, right and wrong do not matter so much as getting a cheer or a laugh.

Eristic powers

Sophists are not only the masters of rhetoric (persuasive speaking) but of eristic. Eristic is the willingness a person has to use whatever tricks they can to win a debate. As the philosopher John Gilbert puts it, “[The] eristic speaker exploits ambiguities and fallacies and is willing to wander into lengthy irrelevance if he believes it will serve his cause.” In short, eristic means treating debate as a sport, and not a philosophical pursuit. Here are three examples of eristic:

The use of false dilemmas. A good debater will try to box in an opponent by defining the range of acceptable positions. To do this, they will often present two or a few options as the only options. For instance, in a debate on climate change, a sophist might claim, “We have to stop all industrial activities now or face certain extinction.” This eliminates a whole spectrum of nuance and mitigative measures.

Ad hominem attacks. Sometimes, attacking a person actually might be philosophically justified, but often it is used to distract or demean an opponent’s arguments. More often, still, it’s used to get a cheap laugh. For example, in a debate about economic policy, the eristic might say, “Well, I for one wouldn’t accept economic advice from someone who buys his suit from Walmart.”

The misdirection. This is a long favorite of the slippery politician. When asked an awkward question or presented with a good argument, the sophist will answer a related or subtly different question altogether. Let’s say a politician is asked about a decline in school results. The eristic misdirection would be to reply, “We have invested more than anyone else in schools and have hired 30% more teachers.” This does nothing to address the problem of declining school results.

Debate night smackdown

The issue of sophistry has taken on fresh importance in an age of social media, online videos, and podcasts. For instance, in June of this year, Joe Rogan offered $100,000 to the physician and vaccine scientist, Peter Hotez, if he would appear on his podcast to debate the famously vocal vaccine denier, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Hotez turned the offer down and social media went into a frenzy. Hotez was a coward, a fraud, or unsure of his own arguments. What’s more likely, though, is that Hotez knows his Plato.

When you host a podcast with ten million listeners, you are likely not concerned with the best arguments or discerning the truth. You are concerned with entertainment. Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is a talented and experienced sophist. He will never be wrong, and he’ll never lose, because he knows all the tricks of the eristic trade. He can duck, weave, and slip his way past all the science and facts Hotez can present. He will swim in a great pool of ad hominem attacks, false dilemmas, and misdirection. And most listeners will be none the wiser. Few people actually care about the truth; they’re here for the spectacle.