What socialism is — according to Michael Harrington

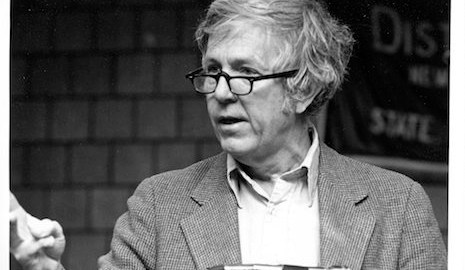

- Michael Harrington was a public intellectual who strove to help the poor. In doing so, he inspired a generation of socialists.

- He was the first chairman of the Democratic Socialists of America, and nearly ran for president in 1980.

- While he is far from the only influential thinker on the American left, his ideas have had an outsized influence over the last sixty years.

The United States is seeing a renewed interest in left-wing ideas. Chicago might have five socialists on its city council by April, a democratic socialist is considered a frontrunner for the Democratic nomination for president, and many Americans like the idea of “socialism” more than the concept of capitalism.

What gives?

A great deal of the credit for this has to go to Bernie Sanders, who campaigned as a democratic socialist, despite not really being one, in the 2016 Democratic primaries. Some of the credit should also go to the members of the Democratic Socialists of America, who have been very successful over the last two years not only in growing their organization but as activists working to make socialist ideas mainstream.

What exactly they say socialism is has a lot to do with the thought of their founding chairman, a public intellectual named Michael Harrington.

Who?

Michael Harrington was an American intellectual known for the book The Other America, which is often credited with inspiring the War on Poverty. A leading socialist, he was involved with several left-wing organizations. He was so well known as a public intellectual that he considered running for president in 1980. His ideas continue to influence the Democratic Socialists of America, who cite him on their history page.

What does he say socialism is?

He talks about what socialism actually is in his book Socialism Past and Future, which he finished writing shortly before his death. After a few chapters of introduction to basic theory and history, he attempts to answer the question directly by looking to what he calls “socialization“:

“Socialization means the democratization of decision making in the everyday economy, of micro as well as macro choices. It looks primarily but not exclusively to the decentralized, face to face participation of the direct producers and their communities in determining the matters that shape their social lives. It is not a formula or a specific legal mode of ownership, but a principle of empowering people at the base, which can animate a whole range of measures, some of which we do not even yet imagine.“

In this case, socialization means democratizing workplaces and economic decisions. This can take many forms, such as giving workers a say on corporate boards as they have in Germany, having enterprises organized as worker-owned cooperatives such as Mondragon, or forcing companies to issue shares of stock to the workers as was proposed in Sweden. At the civic level it can also include participatory budgeting.

His dedication to socialization means that he was able to critique government programs that he found otherwise agreeable. In one case, he praised the work of the government owned Tennessee Valley Authority but pointed out how the people who worked for it or lived in areas it operated in had little more influence over its operations than they would have if it were privately owned.

This doesn’t mean he was utterly opposed to public enterprises or nationalizations, since he understood that in the modern world some things would be hard to manage for the public benefit otherwise, but rather that nationalization also needed socialization to fully realize the goals of the socialist movement.

What did he have to say about the USSR?

As a socialist in the 20th century, he had an opinion on the USSR and often had to compare his vision of utopia with the Soviet model.

Harrington believed that Karl Marx was a democrat in the sense that his political ideology supports democracy. However, he did blame Marx for excessive vagueness and making it too easy to justify dictatorships with his theory. This, he argues, allowed Lenin and Stalin to claim they were following Marx to the letter as they sent vast numbers of working people to Gulags.

He also argued that the Russians, realizing that they could hardly implement socialism in a semi-feudalistic society, hoped to use state control of the economy to modernize rapidly. Using “socialism” to do this was never planned for in Marxist theory and had more in common with the Prussian route to modernization than anything else.

In the Russian model, the state controlled the economy with little or no input from the workers. The state was, in turn, controlled by the communist party with little or no input from the majority of the population who were non-members. He argued that these points made the Russian model “Authoritarian Collectivism” rather than “socialism.”

He then argues that this analysis can be applied to any non-industrialized, impoverished, unstable country that adopts “socialism” as an ideology and then uses it to try and modernize rapidly. He gives the examples of Russia, China, and Cuba as case studies in what not to do when making a successful democratic socialist society. The utter lack of democracy either in the workplace or in the political system being two fundamental problems.

This guy died in 1989, what do his ideas have to do with our problems today?

Harrington’s ideas on what could happen to capitalism in the early 21st century were frighteningly accurate. In his final book, he considers the problem of automation leaving vast armies of the unemployed in the midst of greater economic output than ever seen before. He discusses how this automated unemployment might affect consumer demand and how that would alter the entire economy.

He also considers ecological problems that were only just coming onto the radar in the late ’80s that we are now grappling with. At several points, he discusses the greenhouse effect and posits that capitalism will be unable to fix the problem. Instead, he argues that there must be an international movement dedicated to fixing the issue at the expense of the countries that put most of the pollutants into the air.

His solution to both of these issues is — you guessed it — socialism. In the first case, to assure that in a world where fewer workers are actually needed to produce the goods and services we need can share in what will be the incredible productivity gains automation promises to bring us all. In the second, to help keep us from destroying the planet we live on in the name of a quick buck.

As America continues to consider democratic socialism as a cure for its social ills, the insights of Professor Harrington will be of great use. His ideas continue to influence some of the most prominent voices on the left today and his work continues to inspire those who want to make the world a little more just.