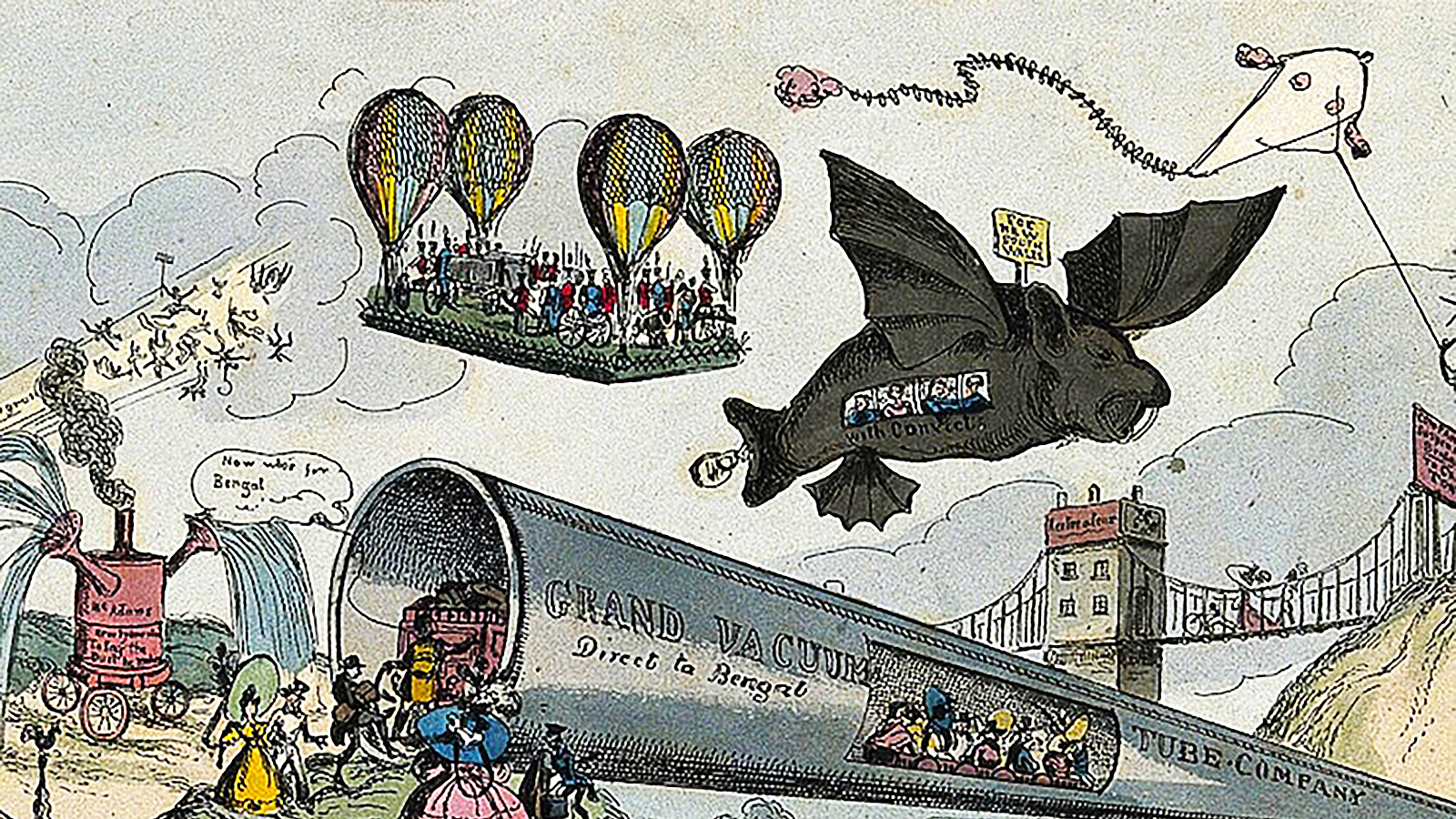

Does science fiction shape the future?

Behind most every tech billionaire is a sci-fi novel they read as a teenager. For Bill Gates it was Stranger in a Strange Land, the 1960s epic detailing the culture clashes that arise when a Martian visits Earth. Google’s Sergey Brin has said it was Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash, the cyberpunk classic about hackers and computer viruses set in an Orwellian Los Angeles. Jeff Bezos cites Iain M. Banks’ Culture series, which unreel in an utopian society of humanoids and artificial intelligences, often orchestrated by “Minds,” a powerful AI. Elon Musk named three of SpaceX’s landing drones after starships from Banks’ books, a tribute to the role they played in turning his eyes to the stars.

Part of this makes sense. Science fiction widens the frontiers of our aspirations. It introduces us to new technologies that could shape the world, and new ideas and political systems that could organize it. It’s difficult to be an architect of the future without a pioneer’s vision of what that future might look like. For many, science fiction blasts that vision open.

Yet these tech titans seem to skip over the allegories at the heart of their favorite sci-fi books. Musk has tweeted, “If you must know, I am a utopian anarchist of the kind best described by Iain Banks.” Yet in Banks’ post-scarcity utopia, billionaires and their colossal influence are banished to the most backward corners of the galaxy.

Recently, I interviewed six of today’s foremost science-fiction authors. I asked them to weigh in on how much impact they think science fiction has had, or can have, on society and the future.

N.K. Jemisin is renowned for her groundbreaking works like The Fifth Season and The City We Became. She crafts narratives that explore themes of power, oppression, and resilience against the backdrop of intricate world-building, earning her global acclaim as a master of speculative fiction.

Andy Weir is best known for his debut novel The Martian, which was adapted into a hit movie in 2015. Weir’s works live firmly in the realm of hard science fiction, fusing meticulous scientific accuracy with gripping storytelling as he explores the ingenuity and resourcefulness of individuals facing extraordinary challenges in space.

Lois McMaster Bujold is celebrated for her Vorkosigan Saga and having won four Hugo and two Nebula awards. She is a master of character-driven storytelling, weaving together themes of identity and the nature of leadership within richly imagined worlds that blend elements of science fiction and fantasy.

David Brin is famed for his works like The Postman and the Uplift series. His narratives often revolve around themes of societal evolution, transparency, and the complexities of human nature, offering insightful examinations of civilizations grappling with technological advancement and their corresponding ethical dilemmas.

Cory Doctorow’s most recent novels are The Bezzle and The Lost Cause, the latter of which he describes as “a solarpunk science-fiction novel of hope amidst the climate emergency.” Both his novels and acclaimed nonfiction delve into themes of privacy and digital rights, offering provocative insights into the intersection of technology and society.

Charles Stross’ notable novels include Accelerando and the Merchant Princes series. Stross explores the implications of technological singularity, alternate realities, and post-humanism, crafting narratives that deftly blend speculative futurism with political intrigue and social commentary.

Does science fiction wind up serving as a blueprint for the future we ought to build?

N.K. Jemisin: It shouldn’t. Science fiction prides itself on being visionary, but like any literary genre, it just ends up examining whatever issues the author is working through in the present. We just do it more allegorically. If you look back at science fiction from 50 years ago, very few writers land on anything close to our present. Lots of those old books accurately predicted certain technologies, but that was all—they didn’t peg how we’d apply them, how we’d break them, how they’d break us. Some of those authors could barely comprehend the idea of women—half of humanity!—as complex beings with their own agendas. Is it a “visionary” prediction of the future when you get one small thing right and flub everything else? Maybe if technology is the only thing you care about. Until pretty recently, science fiction hasn’t been very interested in the bigger picture.

Cory Doctorow: There’s no denying that a lot of people who actually create things are inspired by science fiction. There’s a lot of tangible examples of this. The one everyone cites is the flip phones that were designed by people who were inspired by Gene Roddenberry’s props on Star Trek. Definitely when we think about space travel, all the stuff that people want to do comes from science fiction. So it’s definitely the case that this steers people’s vision of it. But don’t mistake the analogy for a real thing. It’s like people who say what we need to do is all go find Plato’s cave. “Why don’t we track down that goddamn cave?” And so to treat the allegory as real is to miss the fact that it’s an allegory.

Some authors could barely comprehend the idea of women as complex beings with their own agendas.

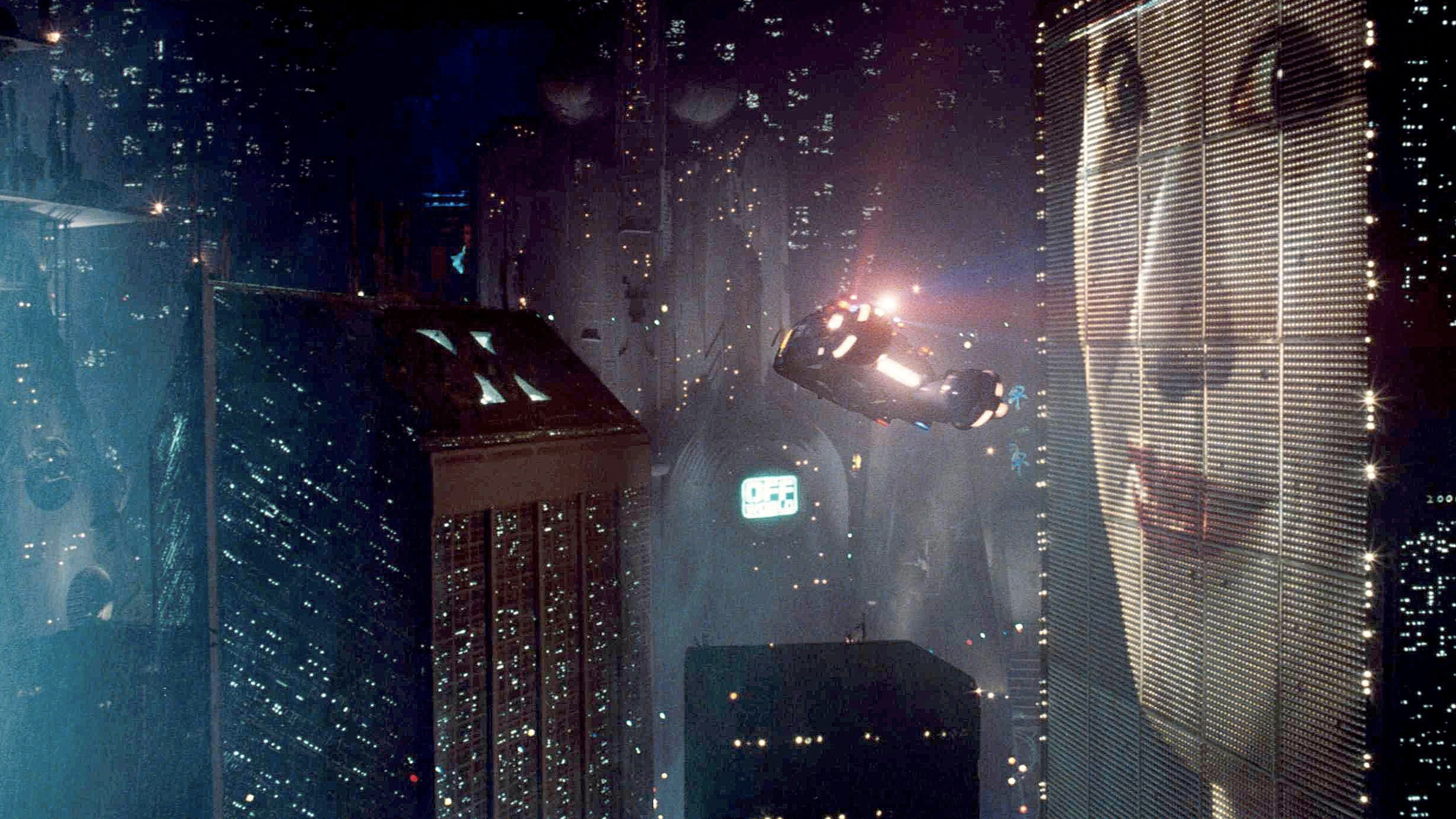

Charles Stross: Once you weed out anything that relies on what I call “magic wand technology”—stuff that ignores the laws of physics—you end up with a very limited subset of science fiction that can serve such a purpose. The trouble is, it’s more often intended as a horrible cautionary warning than as a desirable destination. The futures depicted in dystopian cyberpunk works such as Snow Crash or just plain horrible dystopias like The Handmaid’s Tale are certainly achievable but absolutely shouldn’t be built!

Lois McMaster Bujold: Science fiction does serve as cultural brainstorming, increasing the ambit of the possible. But the fiction part rewards maximizing drama, not sensible, prudent problem solving. These are two different skill sets, not often found in the same persons. So, brainstorming, yes; product development, no. You need Legal, HR, researchers, the shareholders, and the public in on the latter. As they will be financing it all and suffering the consequences of any mistakes.

Beyond inspiring specific technologies, does science fiction ever catalyze real future trends?

David Brin: I’ve spoken to many who avow that science fiction helped—and helps—them to anticipate the future. Science fiction notions have inspired positive tech trends from computers to cell phones and many advances in medicine. But it is the mistakes we manage to avoid, sometimes just in time, that qualify some sci-fi tales as world-changers. Retired military officers testify that works like Doctor Strangelove, Fail-Safe, On the Beach, and War Games provoked changes and helped prevent accidental war. Citizens know little about how many bad things these protectors have averted. While optimism is much harder to dramatize than apocalypse, sci-fi has also encouraged millions to lift their gaze, contemplating how we might get better, incrementally, or else raise grandchildren worthy of the stars.

Andy Weir: I don’t believe that fiction should be considered a tool to steer the real world. I write solely to entertain and for no other purpose. I find morals and agendas in stories to be annoying and they detract from my immersion.

Cory Doctorow: The present is the standing wave, where the past is becoming the future. So if you can change the way people think about the present, you can alter the future. One of the ways to do that is with futuristic allegory. One of the things that science fiction can do that is quite beneficial in terms of how it influences how people think about technology—and this is the thing that cyberpunk did that was so great—is it contests not what the gadget does, but who it does it for and who it does it to. It becomes a question of the social arrangements of the technology more than the underlying technology itself. One of the great lies of capitalism is Margaret Thatcher’s aphorism that there is no alternative. That things have to go a certain way. And at its best, science fiction has people go, “Well, what if we had this gadget that is around us—or that people are predicting will come soon—but it wasn’t controlled by the people who insist that it’s their destiny to control it?”

While optimism is harder to dramatize than apocalypse, sci-fi has encouraged millions to lift their gaze.

N.K. Jemisin: Understanding how society—people—work is key to predicting how the future will develop. That’s how you get Ursula Le Guin exploring nonbinary gender in the 1970s, and Octavia Butler predicting America’s current slide into Christian nationalist fascism 30 years ago. That’s why Star Trek’s best episodes were written by people who understood that you can’t get to that shiny happy hi-tech future until we change first and prioritize things like making sure everyone eats and gets a decent education. I think this is why some of the best predictive science fiction has been written by writers from marginalized groups, and by anyone else who’s had lived experience of society’s uglier paradoxes.

Are there times when science fiction is taken too literally?

Lois McMaster Bujold: I want to answer “all the damn time,” but that is probably an exaggeration. The thing is that the same is true of all fiction. Writers can only control their words-in-a-row; they can’t control how people read them. Each person brings their own experiences, obsessions, traumas, tics, triggers, and limitations to their unique internal construction of what they read, and what comes out the other end of this mental mixer can sometimes have very little relation to what the writer thought they were putting in.

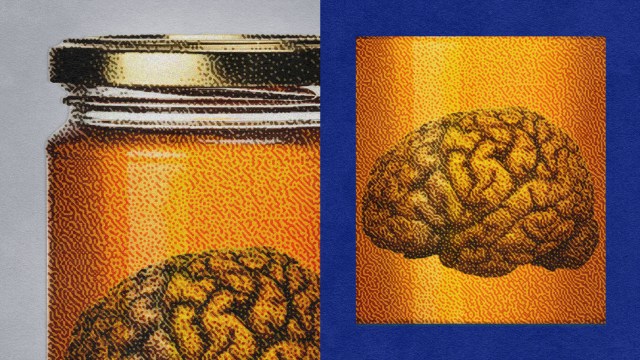

Charles Stross: Yes, the entire current AI bubble is exactly that. The whole idea of AI has been turned into the centerpiece of a secular apocalyptic religion in which we can create superhumanly intelligent slaves that will solve all our knottily human intellectual problems, then work out how to liberate our pure soul-stuff from these clumsy rotting meatbags and upload us into a virtual heaven. And right now, some of the biggest tech companies out there are run by zealots who believe this stuff, even though we have no clear understanding of the mechanisms underlying consciousness. It’s an unsupported mass of speculation, but it’s threatening to derail efforts to reduce our carbon footprint and mitigate the climate crisis by encouraging vast energy expenditure.

Cory Doctorow: I’d say that VR and cyberspace is the big one. It’s a bunch of allegories that are taken for product roadmaps. And the other big one would be AI. These are allegories that are meant to ask us what we mean when we say “consciousness,” what we mean when we say “intelligence,” what we mean when we create a space for moral consideration of something that’s not human, and how the shifting line of moral consideration changes our own relationship to our world—the AI gets turned into a kind of godhead. Then it becomes “let’s go make the godhead.”

Andy Weir: I think sci-fi has been kind of hijacked by dark, dismal technophobia. Shows like Black Mirror are all basically the same thing: “Tech is bad because humanity is bad.” But I think it’s not true. It’s hard to name a technology that has done more harm than good. Humanity is better than people give it credit for.

N.K. Jemisin: A reader’s interpretation is rarely just about the text. What the author writes is only half the story, and what the reader brings to that story—their preexisting fears, prejudices, and understanding of the world or lack thereof—is the other half. I do think it’s fascinating, however, that quite a few of the works cited by billionaires and technocrats who claim inspiration from sci-fi are cautionary tales … about what happens if billionaires and technocrats take over.

As the world becomes more secular, could science fiction give people a sense of meaning by imagining these stories as possible futures?

Lois McMaster Bujold: I have said that science fiction’s sense-of-wonder is the secular version of the numinous awe sometimes sought in fantasy literature. But really, I think people would do better to look to real science, and the stories it tells, for that wonder in real life. There is no ideology or religion yet devised that cannot or has not been used as a vehicle for humans to be horrible to one another. I don’t think just eliminating belief in the supernatural will change that, because the root problem lies in the humans—ultimately, our biology, so perhaps we are back to real science, minus the fiction, after all.

These people are saying “we finally created the utopia of Neuromancer.” And I go, “I don’t think you read Neuromancer.”

Charles Stross: It already has. There’s Russian Cosmism, which started as a Russian Orthodox Christian theologian’s weird-ass speculation in the late 19th century before it mutated and infected the global rocketry community. “Space colonization! It’s our job to be fruitful, multiply, colonize space, and fill the entire cosmos. And then Silicon Valley!” It follows the same structures as apocalyptic Christianity, except it discarded the inconvenient God/Jesus duo in favor of a spurious belief in its own rationality.

Andy Weir: I think the void has already been filled with other things. Notably environmentalism. I think a desire to believe in something greater than ourselves is inherent in human psychology, and we’re not really capable of going for long without something to look up to. And so we are returning to the place all religions begin: nature worship. That’s not to denigrate environmentalism at all, nor am I saying we should ignore the environmental issues we have caused with emissions. I’m just saying that the psychology at play is very similar to religion, and I think it’s scratching that itch that people have to be virtuous. It’s not so bad for people to feel a moral desire to cut emissions. Just like it wasn’t that bad for people to have a religious aversion to murder.

David Brin: Science fiction has already played a major role in the most theologically significant event in history. And it has very little to do with the existence of God. Nearly all prior cultures had mythologies of a Golden Age in the past, when everything and everyone had been much better. Ours is the first major culture to transpose that better world into a possible future that might be built by our descendants. I’m unbothered by the prospect that some of those heirs may be made largely of metal and silicon, breathing hard vacuum as they explore planets and stars on my behalf. What I do care about is doing my job—teaching them, and our regular/organic-style children, too, how to be decent people.

What do you think when you hear Musk, Bezos, or Mark Zuckerberg talk about being influenced by science fiction?

Cory Doctorow: Sometimes I listen to these guys talk and I think, “I don’t know what science fiction you read because it doesn’t sound like any science fiction I read or write.” Which is weird because I think that the first positive review Bezos ever left on Amazon was for my first novel. There’s a scene in A Fish Called Wanda where Kevin Kline’s character keeps misquoting philosophy to his girlfriend, Jamie Lee Curtis, and eventually she turns to him and says, “The central message of Buddhism is not ‘every man for himself.’” These people are saying “we finally created the utopia of Neuromancer.” And I look at them and I go, “I don’t think you read Neuromancer. Maybe you just played Cyberpunk 2077.”

Charles Stross: The thing is, billionaires are not critical readers. They don’t seem to have noticed the subtext of the science fiction they read as kids, much less noticed where there’s a worrying absence of subtext. Noteworthy exception: Steve Jobs. He’s dead now so we can’t ask him, but I suspect his vision for the future of computing was, “I want to build the black monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey.” I can just see teenage Steve getting stoned or dropping acid and seeing 2001 in the cinema and being struck by the vision of a plain back featureless thing that reaches inside the ape-men’s brains and makes them fundamentally smarter. Every device he produced, from the Macintosh onward, had some aspect of the Monolith to it. The only problem is, Jobs’ implementation of the Monolith seems to principally be used to make us angry and stupid, instead of spreading enlightenment.

The whole idea of AI has been turned into the centerpiece of a secular apocalyptic religion.

Andy Weir: I think anything that leads to innovation and funding for research is good. If it’s a cult of personality like Musk, or immense wealth on a man-baby like Zuckerberg, it doesn’t matter so long as the research gets done. That knowledge remains with humanity long after the people who funded it are gone.

David Brin: Depends on which science fiction tales influence them. Those who donate to causes—like saving the planet—because they read novels like Earth or watched Soylent Green may help us avoid dire fates. Alas, some now wallow in prepper fantasies of riding out an apocalypse or “Event” as in some cheap Mad Max flick.

N.K. Jemisin: I don’t think they’re influenced by any science fiction. I think they claim to be because they think it makes them seem smart. Frankly I suspect some of those guys can’t read.

Do you ever think that somebody would read your work and go on to build technologies or make decisions that could impact the future of our species?

N.K. Jemisin: No. For one, I don’t particularly romanticize technology or accord it more power than it actually has. Tech is a tool. Tools do not have the power to change basic human nature; the person you are with a hammer is the same person you are without it. You want to blame the person that first thought up a hammer for what you do with that hammer? Does that make sense? Language is a tool, too—a more complex one, more powerful, but it does not have the ability to control you. So this whole notion that fiction causes people to do things is just so infantilizing and strange to me. Human beings get exposed to new ideas and tech all the time. Our whole lives, from birth till death, we’re adapting to new materials, new methods, new anxieties. How do we adapt/react to those anxieties? That’s the choice. That’s what matters. Anyone who chooses to destroy democracy or wreck the environment was going to do that anyway. A book didn’t “make them do it.” You wouldn’t buy that excuse from a 3-year-old. They made a choice, then blamed a book in order to dodge or dilute their own accountability. We should probably stop buying that excuse from billionaires, too.

Sci-fi has been hijacked by dark, dismal technophobia. Tech is bad because humanity is bad. It’s not true.

Cory Doctorow: It doesn’t matter what you put on the page. There are people who take completely the wrong lesson from it. My first novel is about how horrific reputation economies are and how they produce these winner-take-all economies where you think that you have a meritocracy, but really the people who lucked into a bit of an advantage managed to maintain that advantage over long timescales. And so many people have read that book and sent me well-meaning emails saying “I read your book and I was so excited. Now I’m going to go and build this technology from your book.”

Charles Stross: For the past decade I’ve been writing critical political satire disguised as Lovecraftian horror stories. I’m reasonably confident that Cthulhu isn’t real, so no risk there! I am, however, regretting the lack of emphasis in Accelerando on how terrible the outcome of singularity is for humanity.

What’s the worst technology or idea from science fiction that you’re afraid Silicon Valley might turn into a reality?

Charles Stross: Data mining. And it’s been here for decades and is getting worse. As an editor of mine put it, “the biggest threat to humanity in the 21st century is too much information.” It makes the sort of intrusive police state 20th-century dictatorships wanted almost trivially easy to implement—and the United States is wide open and vulnerable, in the absence of a constitutional-level right to privacy and courts with teeth willing to enforce it in the face of government opposition.

Lois McMaster Bujold: I’m pretty sure Silicon Valley is capable of coming up with all sorts of things I neither want nor need all on their own.

Cory Doctorow: In an era where you can add blockchain to the name of your iced tea company, and increase your share price by $10 million, or add AI to the name of any product, it is all just a way to just make an unfalsifiable claim to being on the cutting edge and having a share in these eventually very large returns that the investor community has assured us are absolutely coming for these technologies. Morgan Stanley keeps saying that AI is a $13 trillion market. And so if AI is a $13 trillion market, then your AI-enabled mascara or fertilizer has some claim on that $13 trillion in value. And so do we need to build AI? And do we need these products to be in a position where they’re making decisions at high speed that are incredibly consequential for actual human beings? Absolutely not.

People would do better to look to real science, and the stories it tells, for that wonder in real life.

David Brin: There are many clichés about AI, like Skynet or The Blob. If these geniuses in the Valley make new entities that are super smart feudal lords or despots of unaccountable blobs, then we might be screwed. But if these new beings have boundaries, individual differences, and some rivalry, then we might use incentives to get some of them to protect us from the worst of them. Isn’t that already what we do with super-smart, predatory entities called lawyers.

Do you see science fiction’s influence on Silicon Valley and its leadership as a net positive, net negative, or entirely negligible?

Cory Doctorow: It’s neither negligible nor is it measurable in a way that would allow you to make an easy characterization of net negative or net positive. I think that it’s very hard to extract the meaning of and the significance of science fiction to technology without also thinking about the relationship of technology to science fiction, right? A lot of the science fiction was written by people who worked in tech and were really excited about it. Personal computers and modems are absolutely coterminal with me going to the science-fiction bookstore in downtown Toronto and buying everything on their 25-cent rack and reading it all. Those two things are influencing people at the same time. So I think it’s a mistake to think, oh, well, science fiction is the literary inspiration for technology without understanding that technology is the inspiration for science fiction as well.

Charles Stross: I think that at this point, Silicon Valley’s culture is self-selecting for people who are compatible with the world view it embodies. It grew out of an industrial revolution initially driven by engineers—and mainly appeals to white STEM-educated males who have been trained to view themselves as the intellectual elite and to believe that all human problems can be solved by the correct application of technology, which is itself the buried theme of Gernsbackian science fiction from the 1900s. The damage is already done.

Can science fiction sway the direction of society?

Andy Weir: Honestly? No. We’re entertainers. When writers forget that’s their main job, their work suffers. No one likes to be preached at. If I can inspire some kids of today to be the scientists of tomorrow, then great. But I don’t think there’s any specific ideas I’ve had that would lead to a scientific breakthrough. I think there’s a very good chance that my profession is going to vanish in my lifetime. If not mine then in my son’s because, like, how long will it be before an AI can just read a million books? Find out what people like about them and what they don’t, and then be able to make a story.

David Brin: We should be treated as the sage visionaries that we are! Seriously, we’ve been at this warning-biz for a long time. The last 100 years of sci-fi is a trove that should be remembered and tapped, whenever anything really strange looms on the horizon; it’s likely some crackpot wrote about something like it in the past.

Lois McMaster Bujold: Brainstorming is science fiction’s proper job. Winnowing the results is a different and weightier task. People don’t, in general, die from reading a bad novel, which is why writing can be one of the most unregulated professions in the world. You can spot the professions that can kill people by all the tests, certifications, and laws that hedge them—engineering, medicine, piloting both air and water, even accounting and law itself. Do not get these two categories mixed up.

Cory Doctorow: Have you met science fiction writers? I mean, they are completely daffy about technology half the time. I don’t have any grip on technology.

This article originally appeared on Nautilus, a science and culture magazine for curious readers. Sign up for the Nautilus newsletter.