Anti-aging isn’t a scam, but immortality almost certainly is

- Altos Labs, a new biotechnology firm, has recruited some of the leading scientists on age-related disorders.

- Age-related disorders occur when one system (such as the neurological system) begins to fail due to cellular stress. This rarely kills the individual, but it reduces the individual’s capacity to live a healthy life.

- Rejuvenating stressed and aged cells has the potential to prevent age-related disorders and improve the human healthy span.

Aging is a particularly troublesome affair, and until recently it was considered to be an inescapable fact of life. Over the past few decades, however, scientists have discovered that aging follows a predictable path. Unsurprisingly, there is great interest in avoiding that path.

As we age, we experience a gradual decline of physiological function. Over time, our cells accumulate damage and their performance suffers. When the damage reaches a threshold, cells die. Fortunately, there is a system for replacing the dying cells — stem cells. Unfortunately, stem cells also age. Consequently, their performance suffers, and they lose their capacity to create healthy new cells.

The new biotechnology firm Altos Labs has recently announced it was taking on aging. At first glance, it is hard to get excited about this. After all, a half-dozen biotech firms have made similar statements over the past decade or so. Altos Labs, which has already secured $3 billion in funding, hasn’t released much information about their strategy, only that they are “focused on cellular rejuvenation programming to restore cell health and resilience, with the goal of reversing disease to transform medicine.” Catchy sales pitch, but not a lot of substance.

Altos Labs has, however, released a lot of information about the scientists they’ve recruited, and it is an impressive list, comprising some of the superstars in aging-related disorder research. These scientists’ backgrounds would suggest Altos Labs has a two-pronged research strategy: 1) reverse the damage that occurs as we age and 2) rejuvenate stem cells’ capacity to create healthy new cells. A spa day and a cocktail, basically.

Cells need a spa day, too

Stress ages us. Thus, one of the keys to living a long and healthy life is to relax. We can’t escape stress, but if we relax after a stressful event, we can escape many of the consequences of stress.

Stress also ages our cells. Admittedly, they aren’t dealing with psychological stress from poverty or global pandemics, but they have their own problems, such as nutrient deprivation and viral infection. These cellular stressors can damage a cell’s proteins, and if there is a lot of damaged protein, a cell can’t function well. Cells cannot escape stress. They may not become infected, but they will suffer some form of stress eventually. Luckily, cells have a mechanism for escaping the consequences of stress: the integrated stress-response (ISR) pathway.

When cellular stressors are detected, the ISR initiates spa mode. However, instead of relaxing while a masseuse rubs away muscle knots, cellular spa mode involves shutting down non-essential cellular operations and cleansing the cell of damaged proteins. If the cleansing is successful, the cell is rejuvenated. If not, then ISR presses the “termination” button. The cell dies, but ideally, a stem cell quickly creates a healthy new cell to replace it.

ISR is more active as we get older, which means cells spend more time in spa mode. A comparison of adult and older male mice demonstrated an increase of ISR activity levels in all tested tissues, including kidney, liver, colon, brain, testes, pancreas, lung, and heart.

However, it is not clear if the increase in ISR activity is a good thing. On one hand, it might promote health in old animals by rejuvenating cells. On the other hand, it might instead contribute to destroying cells unnecessarily.

Destroying a damaged cell can be a good thing, as long as it is quickly replaced with a healthy new cell. However, adult stem cells appear to age with the person. As stem cells age, their ability to create healthy new cells deteriorates. Consequently, a cell might die because ISR has determined it was too damaged, only to be replaced with a cell that is almost equally as damaged.

Essentially, this is like terminating an overstressed employee whose performance has dropped. Then, you wait six months to hire a new employee who is slightly less stressed. A couple months later, you lay off the new employee. During that six-month period, other employees will have to shoulder extra responsibility. Their stress will grow, their performance will drop, and next thing you know, you’ve laid off the whole department. Catastrophic organ failure is the main cause of age-related disorders.

It is tempting to speculate that inhibiting ISR in adults could solve a lot of problems. Sure, there’d be no more spa day, but there’d also be no more mass layoffs. But it’s not that simple. ISR inhibition does enhance memory and lifespan. However, ISR activation reduces the severity of Huntington’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and multiple sclerosis. Thus, the ISR appears to play a beneficial and detrimental role in health depending on the context. Altos Labs scientists will have to gain a better understanding of ISR’s context-dependent effects before they can create new anti-aging therapeutics.

If a spa day doesn’t do it, maybe a cocktail will

No matter how efficient the body is at rejuvenating cells, cells will die and need to be replaced. As we age, however, replacing cells takes more time. For example, healing of a fractured bone takes much longer in older individuals than in younger individuals.

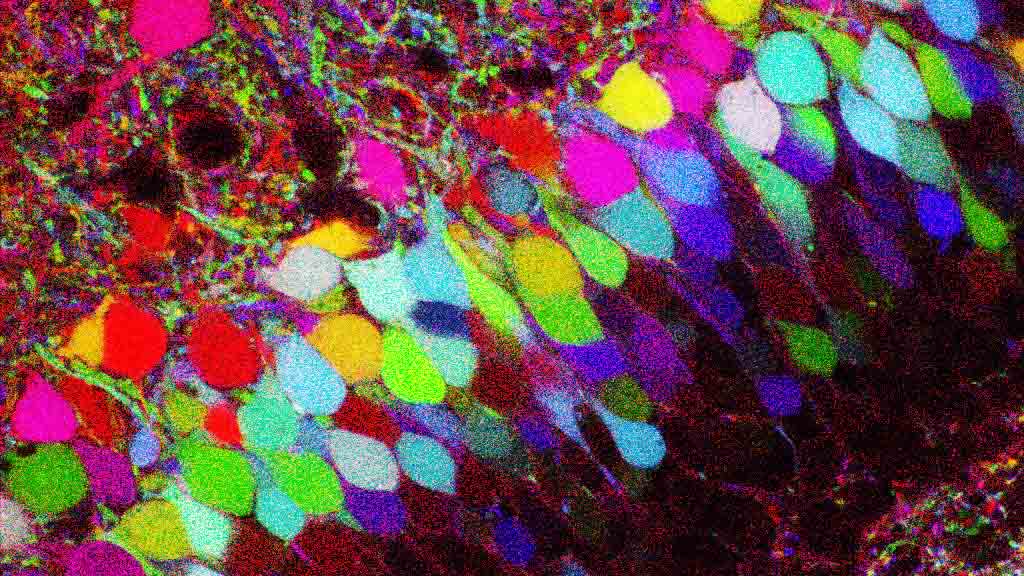

Stem cells are responsible for replacing damaged cells. Like any other cell, stem cells are vulnerable to cellular stressors. This likely contributes to their own aging, but there is also evidence that stem cells’ DNA changes as during physiological aging. More specifically, the DNA’s structure is changed (called an epigenetic change), but not the DNA’s sequence. In other words, regardless of their age, stem cells keep the same genes; however, as stem cells age, some genes are tightly packaged up and no longer accessible.

Epigenetic changes are often helpful. For example, a liver-replenishing stem cell will package up all of its neuron genes. When that stem cell creates a new liver cell, the new cell can’t accidentally express those neuron genes.

But in the case of aging, the epigenetic changes can be harmful. For example, in addition to packaging the neuron genes, an old liver-replenishing stem cell might package up two other genes:

- a cleansing gene, which helps remove damaged proteins during ISR activation.

- a replication gene, which helps the stem cell quickly produce new liver cells.

When a new liver cell is created, it won’t be able to access the cleansing gene. As a result, that cell will have a harder time cleansing itself of damaged proteins. Thus, it will die more quickly and need to be replaced again. Unfortunately, that replacement will be slow to arrive because the stem cell can’t access the replication gene.

It is unclear why a stem cell would gradually package up helpful and important genes. One hypothesis is that this process ensures we will die. When old organisms die, it frees up resources for young, sexually reproductive organisms. Thus, there is an evolutionary advantage to death.

Regardless of why stem cells do this, it would be helpful to discover a way to liberate some of the genes packaged during aging. Scientists have suspected that this could reverse a stem cell’s aging-associated functional decline. In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka discovered the tools necessary to do this.

Yamanaka and his team showed that activating four gene regulators (now referred to as the “Yamanaka factors”) can reset a cell’s epigenetic changes, essentially turning it into a young stem cell. (Yamanaka won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for this discovery, and he is a consultant for Altos Labs.)

However, it’s not as simple as giving cells an endless supply of Yamanaka factor cocktails. When a stem cell is stimulated with all the Yamanaka factors at once, all the genes are unpackaged, resulting in an unspecialized stem cell. This is analogous to resetting your brain to what it was as a baby; your potential would be incredible, but you would need guidance to harness that potential. In the same way, unspecialized stem cells have the potential to become any type of cell, but they will need lots of guidance. And scientists have only begun to scratch the surface on how to guide cells in their development.

However, they might not need to know how to guide development if they want to treat age-related diseases. Researchers recently discovered that moderation is the key to avoiding the problem of unspecialization.

Essentially, stimulating cells with just the right Yamanaka factors at just the right time partially resets the stem cells. These partially reset cells retain their ability to create new cells without extra guidance. Experiments on mice have shown how a partial reset can stop the progression of progeria (a mutation-induced syndrome that mimics rapid aging), can promote the healing of injured muscles, and can protect the liver against medication-mediated damage.

Altos Labs: Improved health span, not life span

Age-related disorders — dementia, arthritis, cancers — don’t significantly shorten our life span. They are often more cruel than that. Instead, they shorten our health span. They steal our memories, our independence, and our tranquility. From what I can tell, Altos Labs isn’t looking for the secret to immortality or even the secret to increasing the human lifespan. They (and all the other anti-aging biotech firms) seem to be searching for a way to make aging less cruel.

So, don’t expect an elixir of life that grants immortality anytime soon. Perhaps in a few decades, we’ll know enough about aging to entertain a discussion about extending the human lifespan. But until then, I suspect spas and moderate cocktails are the best path for aging gracefully.