Alan Watts was overzealous in his basic income prediction — but he wasn’t wrong

Image: Big Think

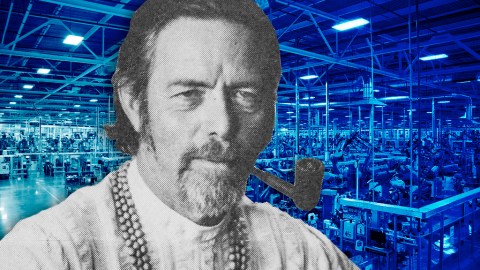

- Economist Robert Theobald coined the team ‘basic living guarantee’ in the 1960s.

- He believed that we were going to suffer problems because of an overabundance of resources.

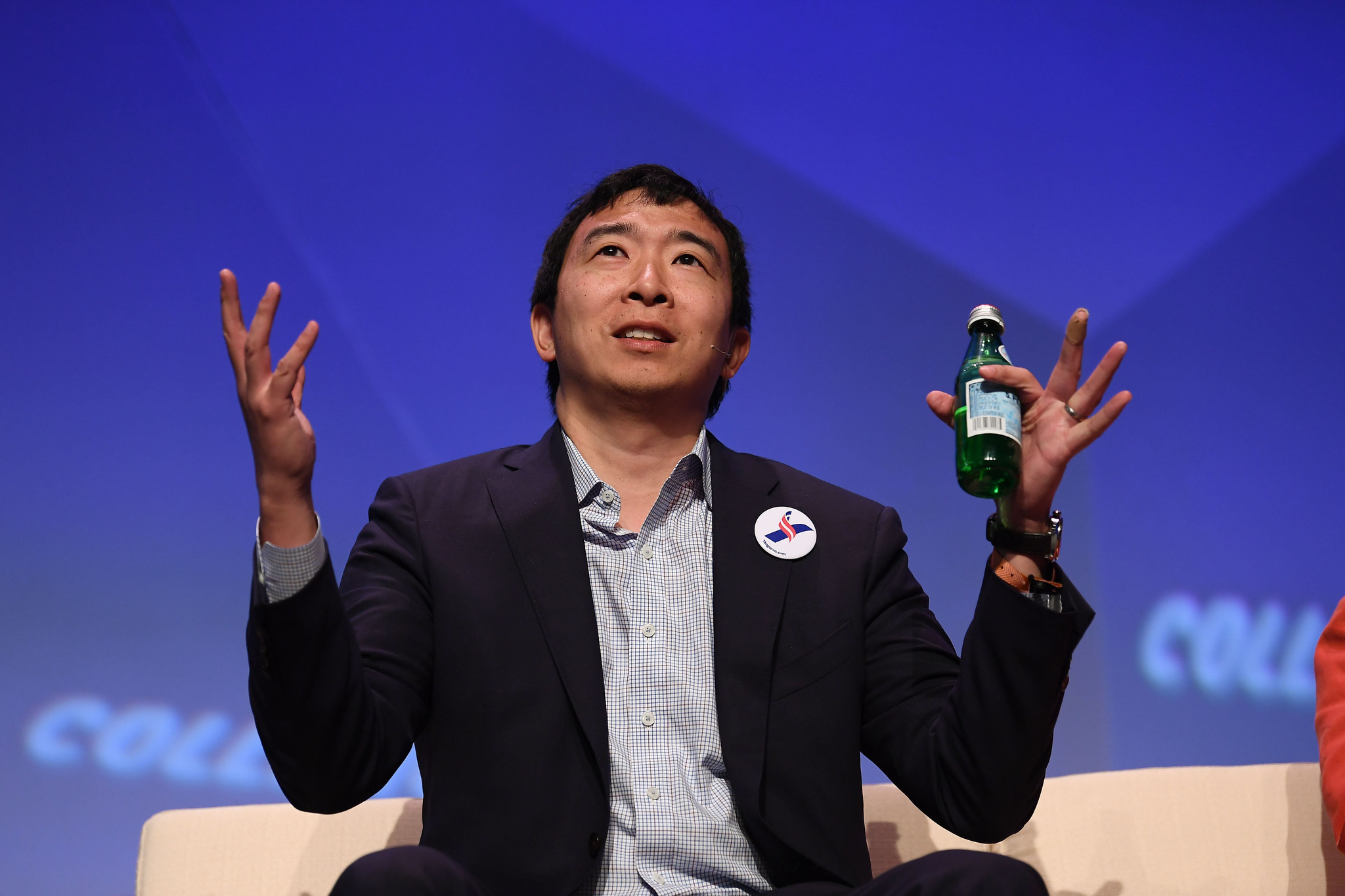

- Philosopher Alan Watts spoke about the possibility of an economic utopia through a universal basic income.

The perceived threat of labor-ending automation, a stratified elite class, and increasingly complex occupations have left some worried about the fate of their livelihoods and jobs. It’s feared that a seemingly useless class may be the end sum of this unfettered march of technological and economic progress.

The answer to this problem, from some corners of academia and governments, has been an enthusiastic call for a basic income – also referred to as Universal Basic Income (UBI) or Guaranteed Basic Income (GBI). This solution to a potential economic catastrophe has actually been floating around for quite some time. In the 1960s, a few philosophers and economists foresaw in the tea leaves this far-off solution for a still growing problem.

Early proponents of a guaranteed income

Economist and futurist Robert Theobald first rang the alarm bells on this economic threat, which at the time didn’t have a name to it. Theobald believed that the threat to the American and subsequently world economy wasn’t one of scarcity but abundance. His views were in direct contrast to the traditional strain of economics worrying more about scarcity. Theobald looked at the technology of the time and realized that the promise of future development would lead to even greater automated abundance in the future.

In his essay, Free Men and Free Markets, Theobald argued that technological progress would free surplus labor and capital in such a way that it would eventually prove detrimental to the society if this excess human capital wasn’t fully utilized. He predicted that the mass of wealth would be transferred largely to the rich, which would fuel dissent and resentment among the lower classes. To avoid the looming disaster, he called for a “basic living guarantee“. Theobald states:

“Unemployment rates must…be expected to rise. This unemployment will be concentrated among the unskilled, the older worker and the youngster entering the labor force. Minority groups will also be hard hit. No conceivable rate of economic growth will avoid this result.”

Philosopher Alan Watts, who at the time called Theobald “an avant-garde economist,”took the idea one step further and tried to imagine what sort of psychological and sociological issues a basic income would rile up. Not only did he imagine what the after effects of this radical change would bring, but what kind of psychic change would be needed to also bring about a new way we think about money.

Automation and basic income

Alan Watts believed that we still place an unjustified fixation on the notion of a job or employment, which he said predates back to our pre-technological days.

“Isn’t it obvious that the whole purpose of machines is to get rid of work? When you get rid of the work required for producing basic necessities, you have leisure – time for fun or new and creative explorations and adventures.”

The problem is we don’t see that as the case. If you follow the outcome of automation to its logical end, you’ll realize that the whole purpose is to eventually eliminate any human interference in rote menial tasks. But if the casualties of this instead creates a new invalid serfdom class, our entire capitalistic structure will become severely strained.

“… we increasingly abolish human slavery; but in penalizing the displaced slaves, in depriving them of purchasing power, the manufacturers in turn deprive themselves of outlets and markets for their products,” writes Watts in Does It Matter?: Essays on Man’s Relation to Materiality.

Those that lose their jobs will live in a more diminished and impoverished state. All the while, there is a surplus of cheap consumer goods being created by the automated factories. On the subject of who should pay for the basic income, Watts said that the machine should – something echoed by Bill Gates in recent years, who suggested a robot tax.

Theoretical outcomes for a universal basic income

Watts was a bit premature on his basic income prediction, but the picture he paints is still one that proponents of UBI look to as the future. Watts said:

“I predict by AD 2000, or sooner, no one will pay taxes, no one will carry cash, utilities will be free, and everyone will carry a general credit card.”

“This card will be valid up to each individual’s share in a guaranteed basic income or national dividend, issued free, beyond which he may still earn anything more that he desires by an art or craft, profession or trade that has not been displaced by automation.”

Inflation arguments abound when talking about basic income. Watts understood at the time that the way people thought about money would prove most of these arguments true.

“The difficulty is that, with our present superstitions about money, the issue of a guaranteed basic income of, say $10,000 per annum per person would result in wild inflation. Prices would go sky-high to “catch” the vast amounts of new money in circulation…”

Watts found inflation arguments to be null if people would simply realize the symbolic nature of currency instead of confusing it with true wealth.

“The hapless dollar-hypnotized sellers do not realize that whenever they raise prices, the money so gained has less and less purchasing power, which is the reason that as material wealth grows and grows, the value of the monetary unit goes down and down.”

While this idea has gained both supporters and detractors in the years since, the main point still stands: Automated abundance is at risk of disrupting the status quo of the past few hundred years.

Later on in his life, Theobald looked back on the foresight he had and its unnerving validity.

“What’s startling to me is that when I started talking about ideas like these 30 years ago, they were so new and strange that people looked at me as if I had two heads. In retrospect, I think I was looked on as something of a cultural clown – a “crazy” who was fun to listen to. The reaction I get now worries me a lot more, because what most people say is, “Bob, today you’re right, but we’re not going to do anything about it.”‘