What are we really doing here? 10 quotes from Yuval Noah Harari

- In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari investigated the last half-million years to understand how we’ve arrived here.

- In Homo Deus, he speculated on how our present course will influence the future of humanity.

- Harari’s insights are strongly influenced by his thoughts on religion, sexuality, and animal rights.

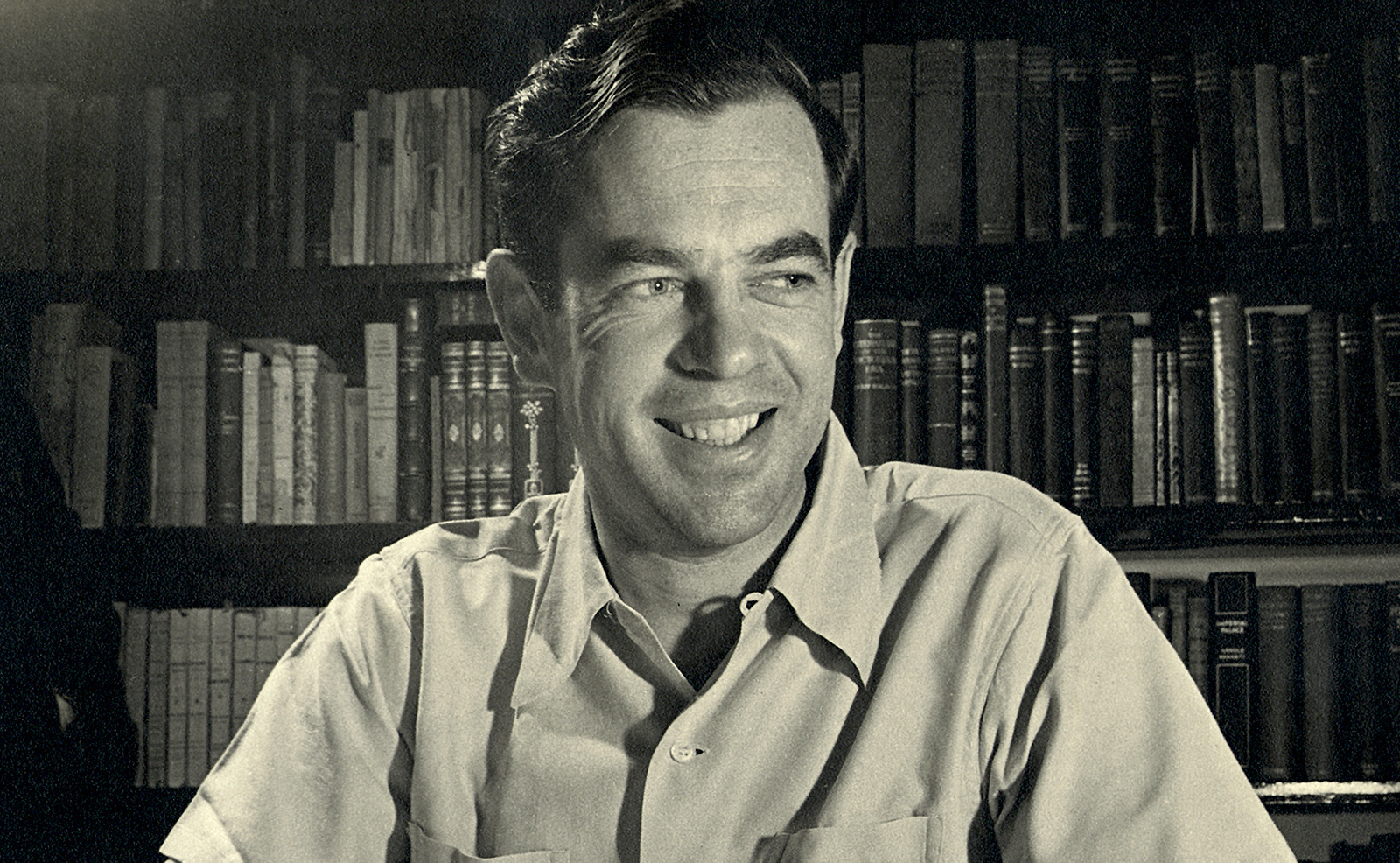

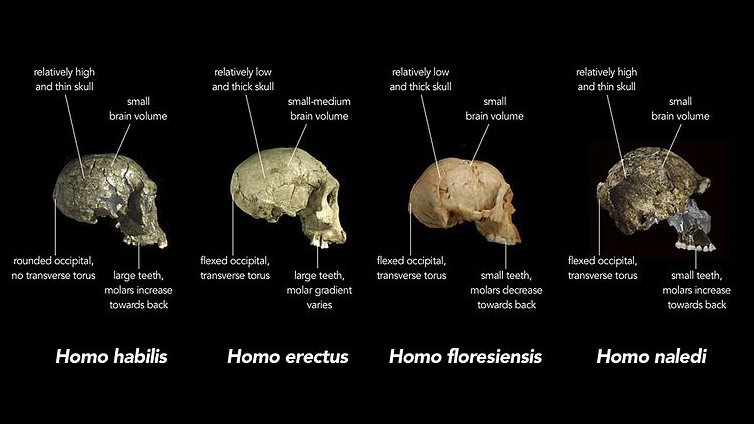

Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari made his mark investigating the transition from Neanderthals to Homo sapiens. His 2014 book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, is that rare history book that made a global impact; the bestseller has been translated into twenty-six languages.

Whereas his debut traced how we got here, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (2016) is a cautionary tale about what “dataism” is doing to our societies and bodies. He takes AI to task, not as a curmudgeonly opponent but more so in the role of a big brother that sees the track you’re heading on and wants to lead you in the right direction.

Throughout his works Harari dissects capitalism, religion, and basic social mores that we’ve overlooked. An ardent practitioner of vipassana meditation and a hardcore animal rights activist, Harari is one of the most reflective and self-introspective historians in existence. Below are ten quotes from his first two books; as I’ve recently ordered his latest, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (2018), I’ll check back in in a few weeks after I’ve finished what he calls his book “about the present.”

Sapiens

The body of Homo sapiens had not evolved for such tasks. It was adapted to climbing apple trees and running after gazelles, not to clearing rocks and carrying water buckets. Human spines, knees, necks and arches paid the price. Studies of ancient skeletons indicate that the transition to agriculture brought about a plethora of ailments, such as slipped discs, arthritis and hernias.

Harari has serious misgivings about modern agriculture. He’s not alone: Jarred Diamond, James C Scott, Daniel Lieberman, and Colin Tudge have all been critical about the move from hunting and gathering to farming. While we can debate the validity of these arguments—city-states and, eventually, nations would not have bound together without food supplies that serviced the necessary scale—agriculture has changed our physical movements for the worse.

It is an iron rule of history that every imagined hierarchy disavows its fictional origins and claims to be natural and inevitable.

You might have heard this one recently: “I alone can fix it.” Trump isn’t the first to claim such; it’s a hallmark of authoritarianism (and wannabe authoritarians).

Most of the laws, norms, rights and obligations that define manhood and womanhood reflect human imagination more than biological reality.

Check out this overview on women and math and science skills. Turns out that if you tell a gender that they’re bad at something, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. But if you don’t prime them in such a manner, the playing field is wide open. Confidence matters.

Monotheism explains order, but is mystified by evil. Dualism explains evil, but is puzzled by order. There is one logical way of solving the riddle: to argue that there is a single omnipotent God who created the entire universe—and He’s evil. But nobody in history has had the stomach for such a belief.

Religion can certainly use a bit more religion. Harari repeatedly reminds his readers of this fact.

If you have a why to live, you can bear almost any how. A meaningful life can be extremely satisfying even in the midst of hardship, whereas a meaningless life is a terrible ordeal no matter how comfortable it is.

See: Simon Sinek, Start With Why.

Homo Deus

Sugar is now more dangerous than gunpowder.

Our imagined enemies are not nearly as dangerous as the ones we pretend aren’t there.

The most common reaction of the human mind to achievement is not satisfaction, but craving for more.

It’s good to constantly up the ante, but at the same time an incessant desire for more is unhealthy. Harari surveys Buddhism in both books, reminding us that Siddhartha Gautama’s great perception is that life is dukkha. Usually translated as “suffering,” a more accurate definition is “unsatisfactory.” The reason we suffer is because we think reality should be what we want, which usually means “more,” instead of facing reality for what it is. This distinction lies at the heart of Buddhism.

Science and religion are like a husband and wife who after 500 years of marriage counseling still don’t know each other.

Maybe science and religion really just need a session with Esther Perel.

We always believe in ‘the truth’; only other people believe in superstitions.

A good reminder on the relativity of “truth.”

Never in history did a government know so much about what’s going on in the world—yet few empires have botched things up as clumsily as the contemporary United States. It’s like a poker player who knows what cards his opponents hold, yet somehow still manages to lose round after round.

Just think of how much truer this statement is than when it was written in 2016.

—

Stay in touch with Derek on Twitter and Facebook.