How plague reshaped colonial New England before the Mayflower even arrived

The Europeans who began colonising North America in the early 17th century steadfastly believed that God communicated his wrath through plague. They brought this conviction with them – as well as deadly disease itself.

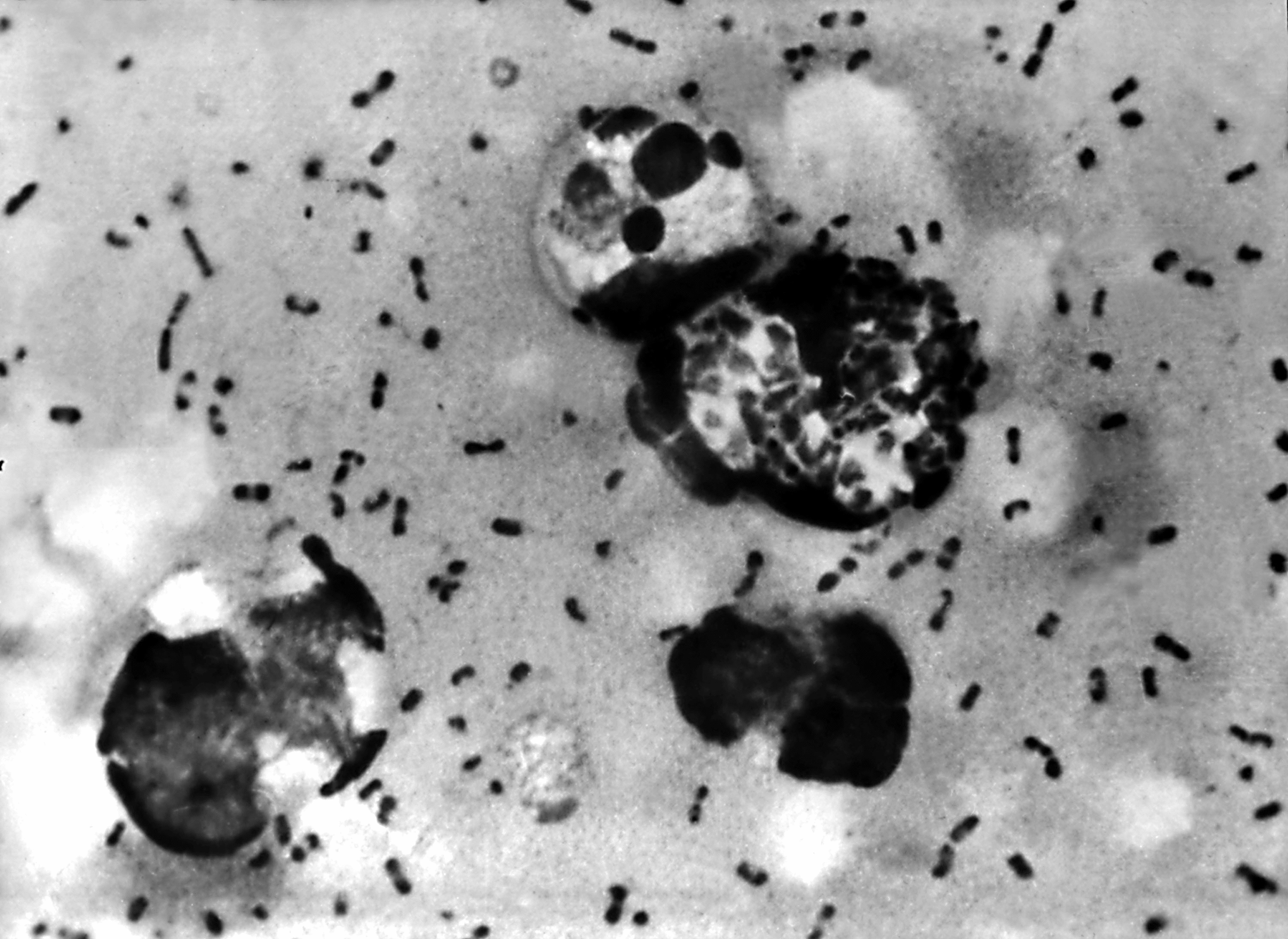

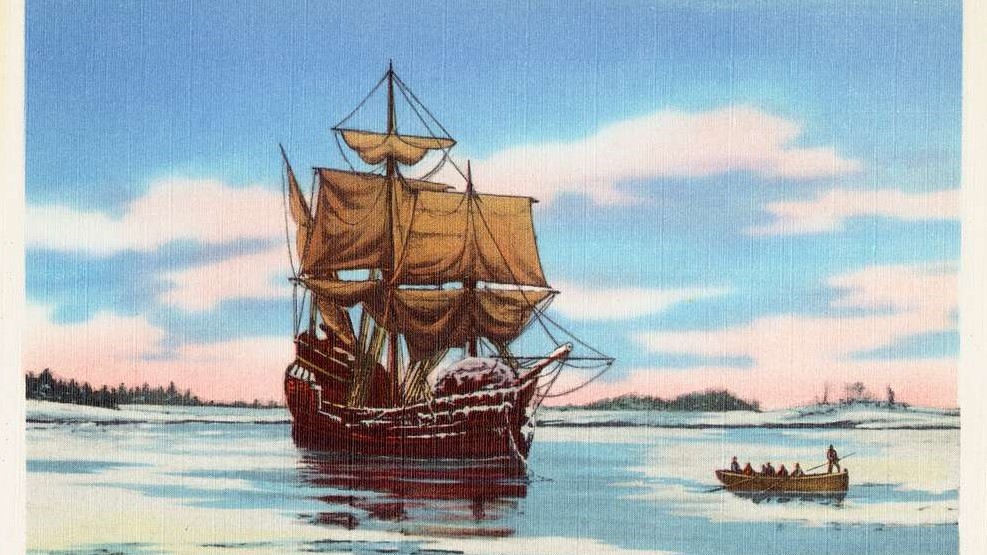

Plague brought by early European settlers decimated Indigenous populations during an epidemic in 1616-19 in what is now southern New England. Upwards of 90% of the Indigenous population died in the years leading up to the arrival of the Mayflower in November 1620.

It’s still unclear what the disease behind the epidemic actually was. But this was the first of many plagues that swept through Algonquian territory – Algonquian being the linguistic term used to describe an array of Indigenous peoples stretching, among other places, along the northeastern seaboard of what is now the US.

The 1620 Charter of New England, given by King James I, mentioned this epidemic as a reason why God “in his great goodness and bountie towards us and our people gave the land to Englishmen”. Plague supported property rights – it informed the back story of Plymouth Colony that was founded after the arrival of the Mayflower.

The English believed God communicated through plague. But my research argues that declaring “God willed the plague” simply opened, rather than closed, the debate. Rulers, explorers and colonists in the 17th century had an interest in pinpointing the cause of disease. This was partly because plague was used to procure land deemed as empty, and even clear it of inhabitants.

Justification for entering the land

Many colonists described New England as an “Eden”. But in 1632 the early colonist Thomas Morton said the epidemic of 1616-19 had rendered it “a new found Golgotha” – the skull-shaped hill in Jerusalem described in the Bible as the place of Christ’s death. Most pilgrims and puritans viewed plague as a confirmation of divine favour toward the English, in part because few of the colonists died in comparison to the Algonquians of New England. Colonists often referred to Indigenous peoples’ bodies as more healthy and fit than European ones, and this sense of physical disparity made the subsequent decline of Algonquians seem all the more striking.

John Winthrop, the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, argued in 1629 that God providentially removed most of the original inhabitants before the colony was planted. A few years later, in 1634, he wrote that God continued to “drive out the natives” and that God was “deminishinge them as we increase”. The right to possess a previously occupied land rested in part on the belief that God had personally removed the original inhabitants. Arguments similar to Winthrop’s litter the landscape of early colonial reflections.

Yet, reactions to the epidemic are far more complex than a simple narrative of land acquisition. Some thought God plagued Algonquians and that it was their duty to try to save their lives and souls. In one 1633 account, compassionate acts for the afflicted coexisted with thankfulness that God was clearing the land – however mutually exclusive those two emotions seem.

Some Algonquians connected the plague with the English and their God. According to Edward Winslow’s Good Newes from New-England in 1624, some thought the English had buried the plague in their storehouses and could use it against them at will. The English tried to dispel the notion that the plague was a weapon they wielded.

Shifting attitudes

Over the 17th century, additional plagues swept through different Algonquian regions at different times. These waves of disease upset indigenous power relations and contributed to the Pequot War of 1636–38 – a conflict between the English and their Mohegan allies and the Pequot which resulted in the massacre and enslavement of the Pequot.

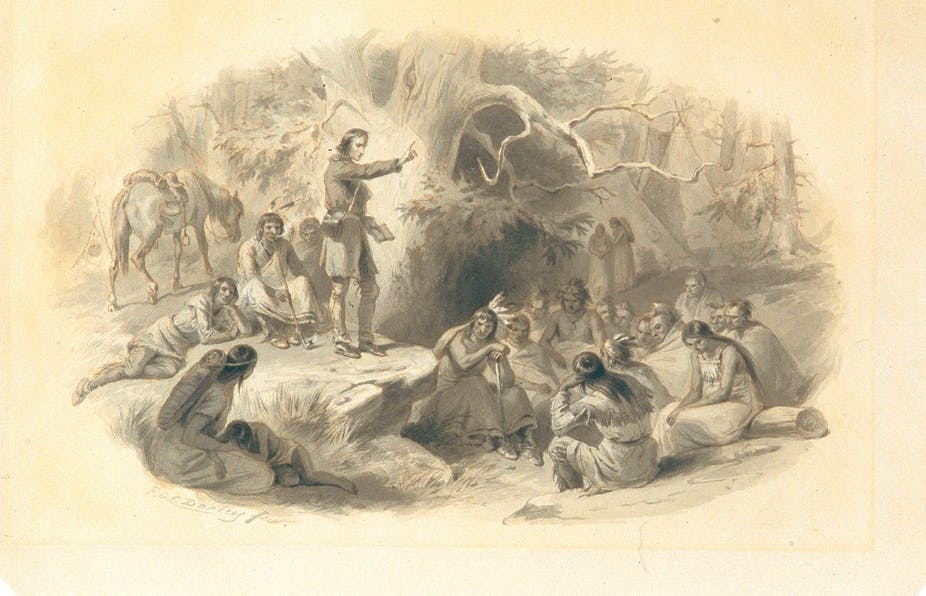

After the war, the English took a more active role in “civilising” and evangelising Algonquians, for example founding an Indian College at Harvard in the mid-1650s. The inclusion of Algonquians into Christianity seemed to contradict the colonists’ earlier view that God had evicted them from the land through epidemic. Some now argued American Indians descended from Israel and their conversion would usher in God’s kingdom on earth.

Decades of disease also influenced Native American spirituality. The trauma of the previous decades – plague being only one factor – made some Algonquians receptive to evangelistic efforts. Some shifted loyalty (at least in part) to the English and their God and their split allegiance undermined traditional authority structures and exacerbated tensions with the English.

Justification for clearing the land

English attitudes towards land acquisition ranged from contract to conquest. Most Englishmen thought taking land from Algonquians was wrong, but over time land transactions gave way to conquests.

It was the emptiness of the land due to plague that justified initial settlements – and over the decades the English purchased additional lands that were occupied. But this arrangement proved insufficient as the decades wore on and tens of thousands of immigrants from Europe wanted more and more land. Roger Williams – a defender of Indigenous people and founder of Rhode Island – critiqued what he called the growing worship of “God Land” .

The early colonists mainly viewed themselves as passively being pulled by God into a void left by plague. Over time they transitioned to viewing themselves as more actively involved in repelling Algonquians, clearing the land of inhabitants with God’s help.

King Philip’s War in 1675-78, a conflict that involved almost all of the European and Indigenous inhabitants of New England, was disastrous for the English victors and much worse for the defeated Algonquians. After the earlier Pequot War, many colonists had come to believe their destiny was tied to the well-being of Indigenous Americans. But after King Philip’s War, destiny seemed to pull them apart.

The growth of racial theories coupled with the recent conflict fed the belief that the English and Algonquian could not coexist. This belief, in turn, led to the myth of the “vanishing Indian” – Indigenous populations declined through plague and war as God strengthened the English. Evangelism receded. Slavery increased.

Expulsion of Indigenous Americans from their lands became more widely accepted after the mid-1670s. The English increasingly saw themselves as pushing American Indians out, with divine approval. This shift would have profound implications for the long and deadly history of white expansion in North America.

Throughout the 17th century, plague invisibly reshuffled the relationship between colonisation, “civilisation”, evangelisation and racism behind the scenes. In doing so it played an important role in altering the political and religious landscape of America.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.