Cave paintings reveal what extinct animals may have looked like

- Cave paintings can tell us a surprising amount about the appearance of animals that no longer exist today.

- In Arnhem Land, rock art helps us distinguish Tasmanian tigers from marsupial lions, and even uncover the locomotion of a giant kangaroo.

- But Australia isn’t the only place where you’ll find extinct species immortalized by human artwork.

Australia has more prehistoric cave paintings than any other country in the world. Most of these paintings can be found in Arnhem Land. Located on the northern edge of the so-called Northern Territory, this region is thought to have been the place Australia’s first settlers entered The Land Down Under around 60,000 years ago.

The rock art itself may well be just as ancient, though it is difficult to know for sure. Because cave paintings usually lack the amount of organic material required for carbon dating, they are notoriously difficult to study. That said, ochre crayons discovered near the paintings were found to be at least 50,000 years old, giving researchers an estimate for the art itself.

Like the Lascaux cave in France or the Bhimbetka Rock Shelters in India, the cave paintings of northern Australia mainly depict creatures. Some paintings clearly represent koalas, dingoes, and other Australian staples. Other paintings are a bit more difficult to decipher. They could depict chimeras: creatures dreamt up by the imagination of Aboriginal artists.

A more exciting theory, however, is that they depict animals that have since gone extinct. It’s certainly possible. Though we have a vague idea of what most of Australia’s megafauna looked like, many of our reconstructions are based on incomplete skeletons, and skeletons can be misleading since they give us no impression of things like fur, fat, or sexual dimorphism.

This puts researchers in a unique position. While technological advances are constantly improving our ability to peek into the past, we may — in this case — be able to learn more about the appearance and distribution of Australia’s extinct megafauna by taking a closer look at the crude but deliberate crayon sketches left by long-dead humans.

Tasmanian tiger or marsupial lion?

One of the animals that pops up regularly in Australian cave art is a medium-sized, dog-like quadruped. Sketches of this animal have been found in Arnhem Land, at the Djulirri rock art complex, and the Kimberly, west of Arnhem Land. At first glance, the paintings seem to resemble Tasmanian tigers: a marsupial predator that was hunted to extinction in 1982.

However, closer inspection would suggest the paintings show the features of a far more ancient species called thylacoleo, also known as the marsupial lion. The jaws of thylacoleo were broader and shorter than those of the smaller and more delicately built Tasmanian tiger. True to its name, the marsupial lion also had large, heavy forelimbs with long claws.

The painting in Kimberly is an admittedly closer match than the one in Arnhem Land, which seemingly combines features of both thylacoleo and the Tasmanian tiger. The front legs of the creature in the painting are thinner and smaller, like a Tasmanian tiger. At the same time, the creature is painted without stripes on its rear half — the tiger’s most distinct characteristic.

Virtually all other cave paintings depict Tasmanian tigers with stripes. As such, archaeologists Paul S.C. Taçon and Steve Webb propose the Arnhem Land ART originally depicted a thylacoleo, but that the original image was painted over after thylacoleo had gone extinct (c. 30.000 years ago) by an artist looking to represent the animal that had taken over its niche: the Tasmanian tiger.

The mystery of the giant kangaroo

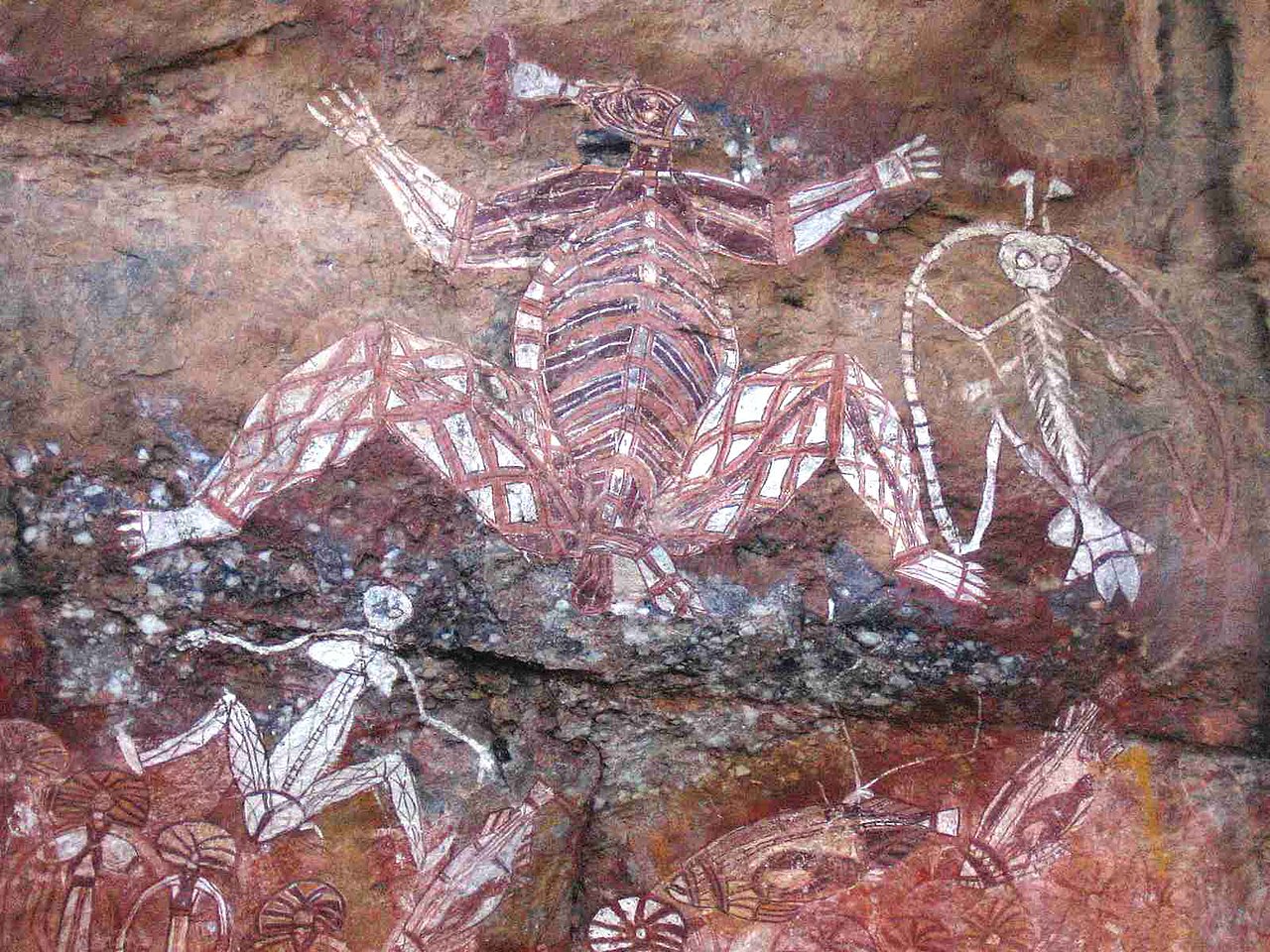

With conservation being a modern concept, it’s not uncommon to find rock art painted atop older rock art. Another example of this practice can be found at the Ubirr rock complex in Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory. Here, obscured underneath a number of smaller paintings, researchers discovered the image of a giant kangaroo.

This kangaroo, as PBS Eons pointed out in one of their videos, does not resemble kangaroos as we know them. It’s got a thick body with a long neck. Instead of standing upright, it is hunched over — a position Australia’s red and gray kangaroos rarely assume. Its tail is thick from beginning to end rather than tapered, and — most curious of all — it has a short rather than deer-like muzzle.

In order to identify the creature in the painting, Taçon and Webb lined up seven of the 23 species of short-faced kangaroo known to have lived in Australia after humans first set foot on the continent. Next, they simply worked out which of these seven species shared the highest number of features described above.

One of the strongest contestants turned out to be Procoptodon goliah. Showing up in the fossil record as early as 46,000 years ago, it was twice as large as modern-day kangaroos. It was also too heavy to hop, leading researchers to suggest that it may have had to stride instead, while partially supporting itself with its forelimbs, thus explaining its position in the rock art.

Side note: One of the smaller images drawn atop the Ubirr kangaroo depicts a bulky bird covered in feathers but without wings. Its neck is painted with a different crayon, suggesting distinct plumage types or colors. The painting could depict the extant emu or another extinct form of flightless bird, like Genyornis newtoni, which had a broader and flatter beak than emus.

Elephants in the Amazon

Australia isn’t the only place where rock art preserves encounters between people and extinct megafauna. Hidden in the Amazon lies an 8-mile-long stone canvas left by the rainforest’s very first inhabitants. Thousands of paintings, all created between 11,800 and 12,600 years ago, depict animals that were last seen in the area during the end of the most recent ice age.

These include the mastodon, prehistoric elephant relatives that belonged to the same family as mammoths. Such creatures might seem out of place in the Amazon today, but as researcher Mark Robinson explained to the BBC, “they moved into the region at a time of extreme climate change, which was leading to changes in vegetation and the make-up of the forest.”

On the other side of the globe, in a cave in western Madagascar, researchers discovered a cave painting that is thought to depict Megaladapis. Also known as the giant lemur, these primates were able to grow to the same size as gorillas, and would have occupied the island alongside other now-extinct megafauna, like the equally massive elephant birds.

How the giant lemur went extinct is up for debate. Elsewhere, rock art depicts humans hunting a contemporary, the sloth lemur, with dogs and weapons, suggesting the giant lemur might have met a similar fate. According to Julian Hume, a researcher at London’s Natural History Museum specializing in the Indian Ocean, this cave painting is the only image of the giant lemur ever found.