Balkanatolia: Discovery of ancient continent resolves long-standing biological paradox

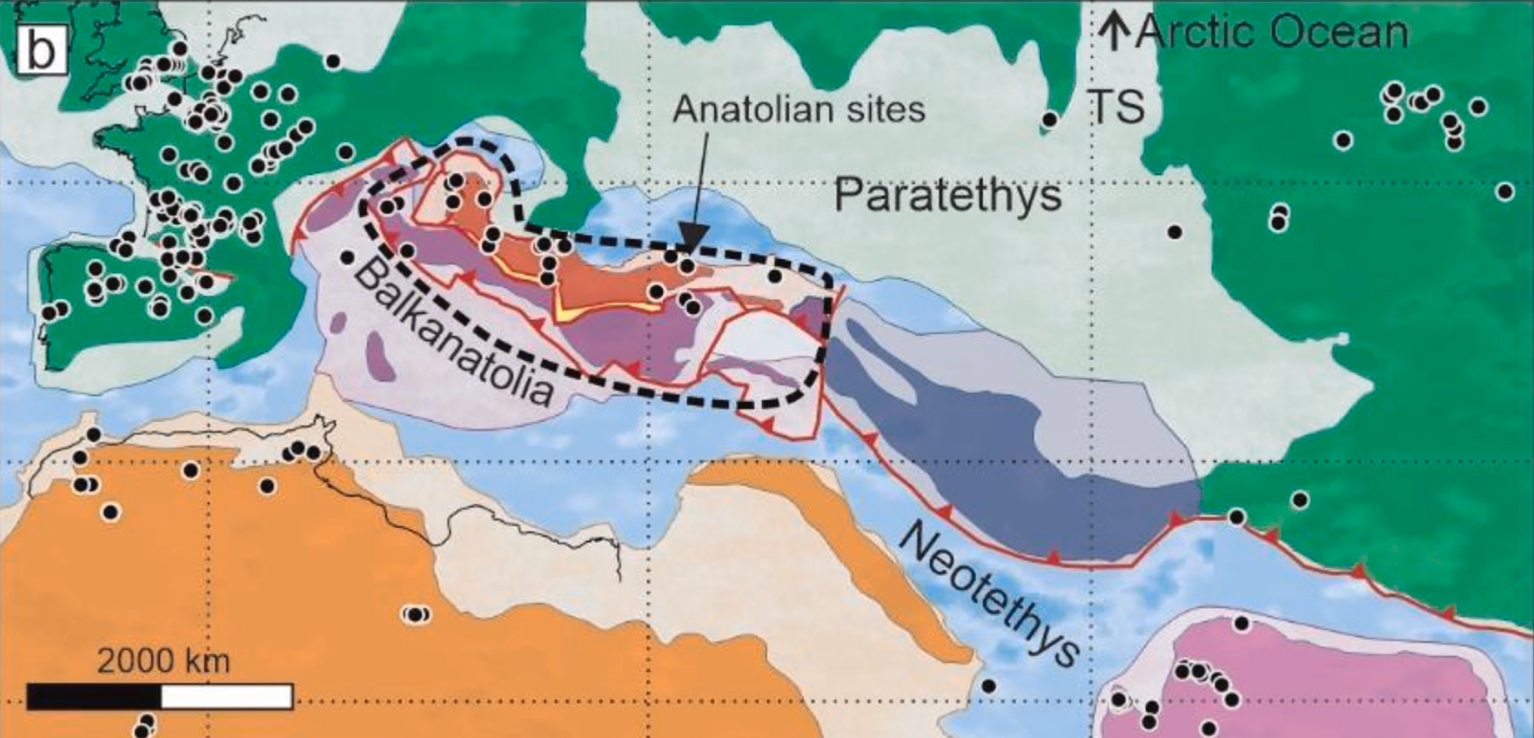

- A group of international researchers proposed the existence of an ancient continent between western Europe and eastern Asia, terming the landmass “Balkanatolia.”

- This forgotten continent, which includes parts of the present-day Balkans and Turkey, may have formed a southern passageway for Asian mammals to colonize western Europe.

- Balkanatolia biodiversity was rich with exotic mammals that were eventually outcompeted by Asian mammals migrating toward Europe.

During the Eocene Epoch (55 to 34 million years ago), hippo-like mammals the size of elephants roamed small islands between present-day eastern Asia and southeastern Europe. This unique mammal had other exotic fauna, like giant marsupials, for company. Eventually, we found their fossilized remains in Anatolia, a peninsula that makes up much of modern-day Turkey.

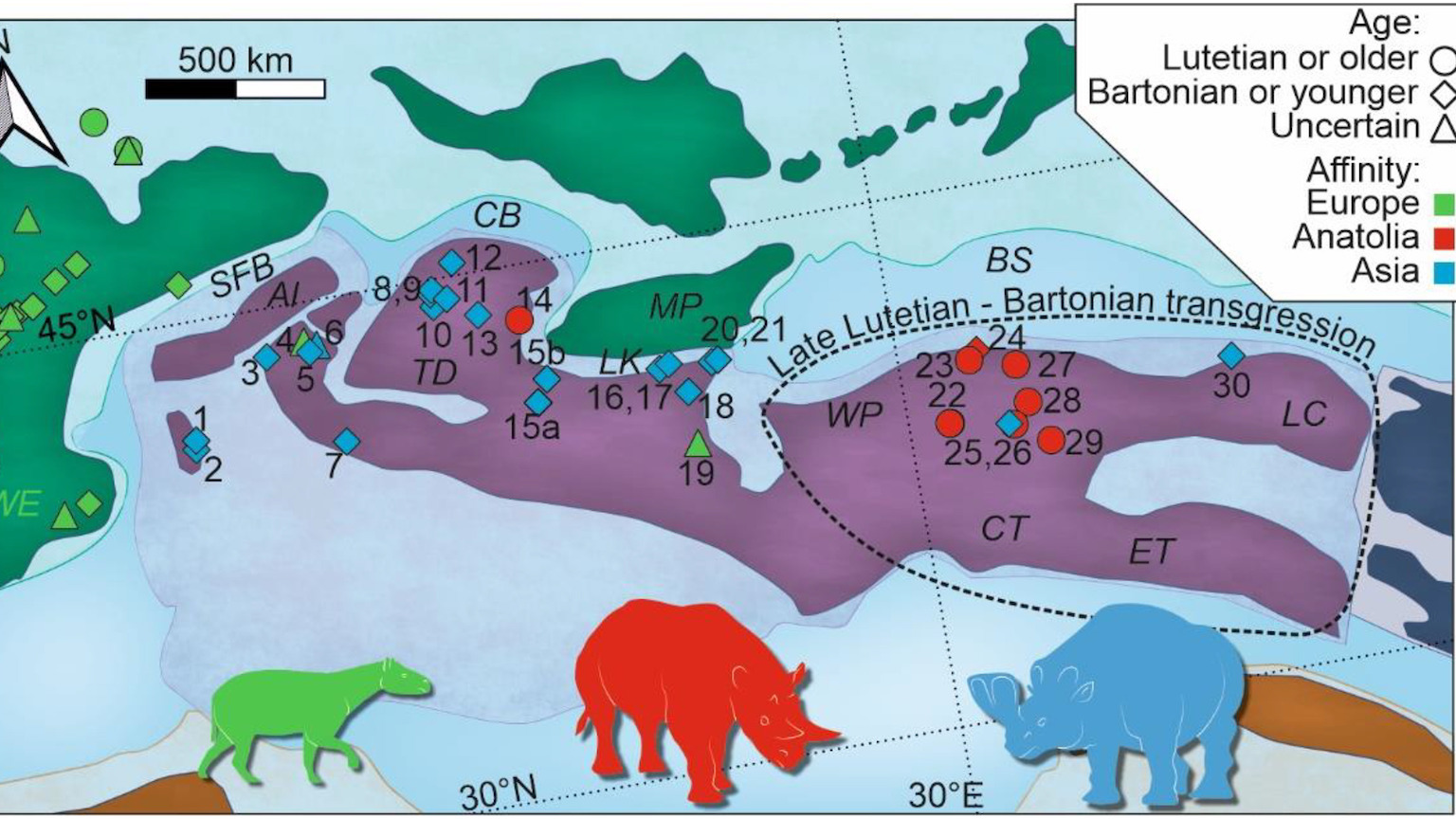

When researchers from France, Turkey, and the U.S. traveled to Anatolia to examine these bizarre fossils, they hoped to explain how these animals — which were unlike any others found in Europe and Asia — wound up in the region. After reviewing existing research and uncovering additional fossils, the team was surprised by the most logical explanation: the existence of a distinct, isolated continent between western Europe, Africa, and eastern Asia. The group of researchers dubbed this forgotten continent “Balkanatolia.”

In a paper published in Earth Science Reviews, the international team led by Dr. Alexis Licht, affiliated with the University of Washington and Marseille University, provides a synthesis of the biogeographic history of Balkanatolia and explains how this landmass may resolve the chronology of mammalian dispersal from Asia to western Europe.

Balkanatolia sets the stage for mammalian battle

During the Eocene, western Europe and eastern Asia were separated by sea barriers that blocked the movement of large animals between the two regions. However, in the early Oligocene, 33.9 to 33.4 million years ago, mammals from the two areas suddenly met, thanks to glaciation and sea-level drop. The animals clashed, with Asian mammals replacing western species via predation and competition. Researchers pieced together this history using fossils of Asian taxa-like ungulates and rhino-like mammals found in Europe. Evolutionary biologists term this period the Grande Coupure (the “big cut”), which refers to the extirpation of western mammals by Asian competitors.

However, there are gaps in our understanding of this massive mammalian migration. In fact, fossils of Asian mammals in the Balkans discovered decades ago suggest that some Asian fauna began to colonize southeastern Europe as much as 10 million years before the Grande Coupure. Since then, a critical question has lingered unanswered: How did the Asian mammals gain access to the European continent?

Researchers have long wondered whether a group of fragmented islands between eastern Asia and western Europe, the area now identified as Balkanatolia, could have formed a passageway for these mammals to reach Europe by island hopping or crossing emergent land during episodes of low sea level. Though this theory would neatly explain the emergence of Asian fossils in Europe before the Grande Coupure, it was unclear whether fragmented islands were ever connected. Since Balkanatolia fauna was made up of unique, endemic mammals, it seemed more likely that the area was physically isolated from the rest of the world. These Balkanatolian mammals included embrithopods, the enormous hippo-like mammals originally from Africa.

Thus, though the idea of Asian mammals traversing Balkanatolia makes sense, it has been hotly debated among researchers who posit that Asian mammals must have found another way into Europe; otherwise, we would see more of their fossils in Balkanatolia in the periods leading up to the Grande Coupure. When Licht and his team traveled to Anatolia and southeastern Europe, however, they found evidence that these fragmented islands became connected into one large continent at one point.

Key fossils in Turkey resolve the debate

Licht and his colleagues were able to settle the debate with the discovery of a new site in Turkey that contained fossilized remains of Asian odd-toed ungulates and rodents from 38 to 35 million years ago — at least 1.5 million years before the Grande Coupure. These records have provided us with the missing biological link to show a dispersal event of Asian mammals across Balkanatolia.

The fossil record also suggests that these Asian immigrants rapidly replaced the endemic Balkanatolian mammals, which mirrors the extinction events of the Grande Coupure in western Europe. In fact, the hypothesis that Asian species caused the extinction of Balkanatolinan mammals via predation and competition aligns with our understanding of island ecosystems, whose endemic taxa are very susceptible to competition by invaders.

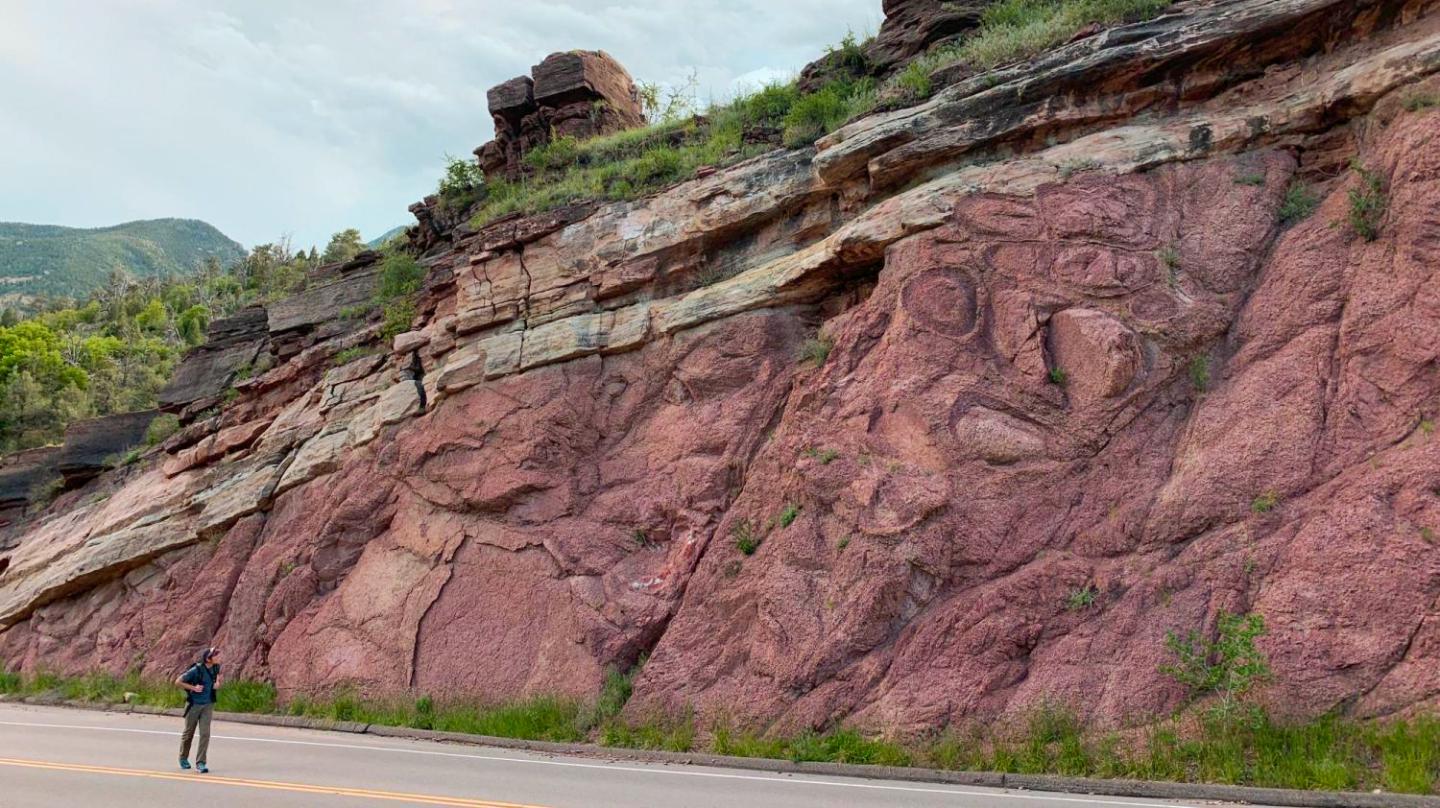

However, the associated climatic and geological changes that coincided with this takeover are less well understood. For example, we still do not know precisely when the fragmented islands of Balkanatolia linked together. The current data suggest that many of the shallow seaways separating Balkanatolian islands retreated somewhere between 47 and 41 million years ago, uncovering an area of roughly 1.6 times the size of Madagascar. Though this area experienced many further drowning and emergence events, it likely served as a southern bridge that connected Asia to western Europe.

Once the landmasses were connected, mammals were suddenly free to migrate between the three areas and expand their ranges.

The rise and fall of Balkanatolia

Today, large parts of Balkanatolia are again under the sea, mainly beneath the waters of the eastern Mediterranean. Though its discovery has helped researchers fill in the gaps of mammalian evolution, finding a once-lush independent continent has prompted new curiosities and questions.

Undoubtedly, Balkanatolia contains many secrets awaiting to be uncovered, not only in terms of cataloguing a rich endemic fauna but also in documenting the history of the rise and eventual fall of rich island biota. To learn more about the continent, researchers will have to keep digging.