The 3 disciplines of Stoicism: A guide for living a life of meaning and intention

- Stoicism has become incredibly popular in the last decade.

- The three disciplines of Stoicism teach us how to step back, act with intention, and improve our relationship with the world.

- For Stoicism to be a philosophy of life, it’s not enough to make one’s life better; a Stoic must make the world a better place for others, too.

How does a person live a good, meaningful life? Many schools of philosophy and religion have attempted to answer this important question. The result of their efforts is a long history of diverse beliefs and etiquettes — some of which have aged incredibly well, others of which not so much. Stoicism is one such school of philosophy, and while its heyday appeared to have ended 2,000 years ago, it may in fact just be getting started.

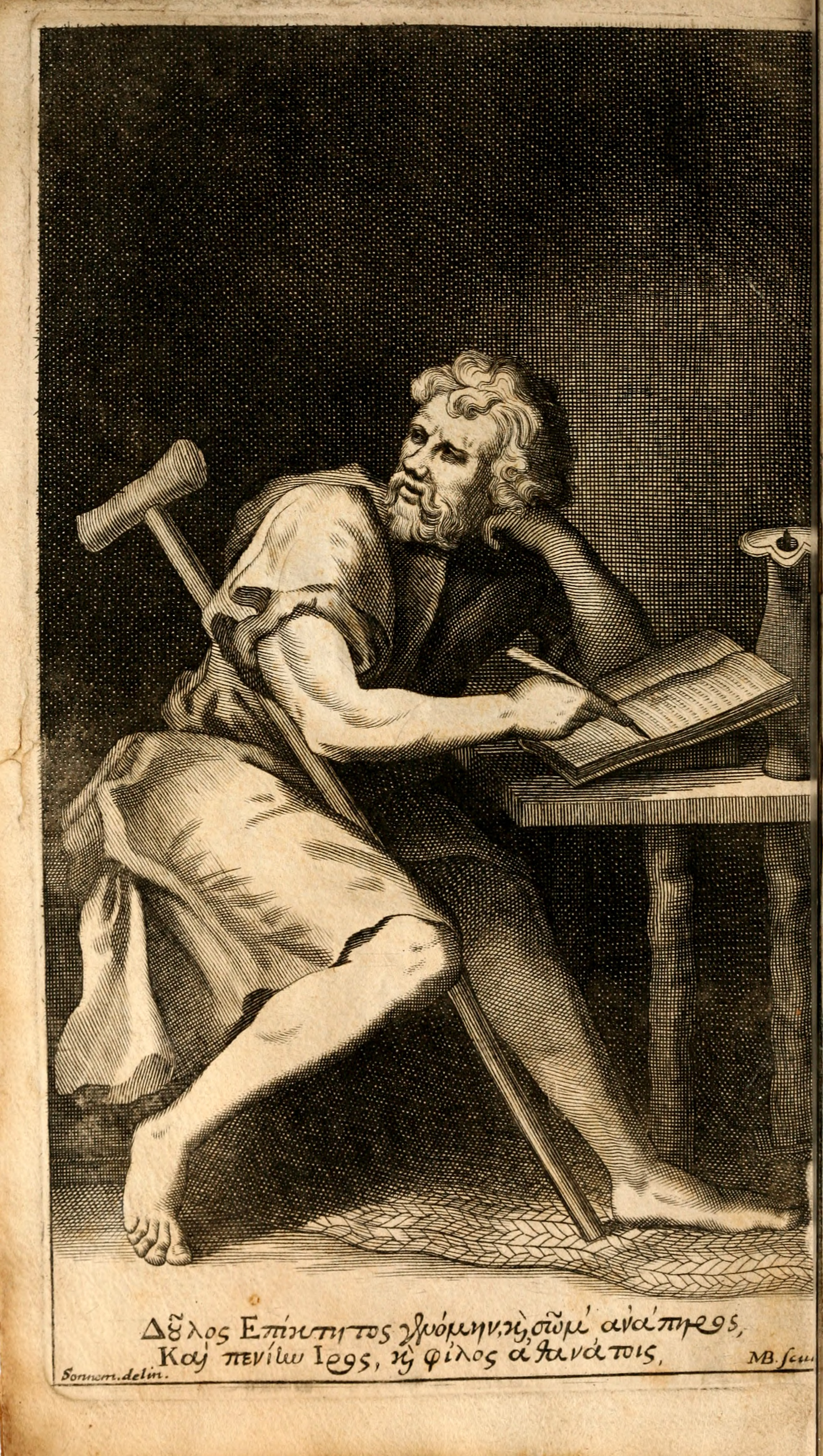

Founded by Zeno of Citium in the 3rd century BC, Stoicism unified logic, ethics, and metaphysics into a coherent philosophy of life. The school would evolve throughout the Hellenistic period and, like so much of Greek culture, would eventually migrate to the Roman Empire. There, it found some of its most well-known and influential voices: the former-slave Epictetus, the statesman Seneca, and the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius. Stoicism would decline around the time Christianity became the Empire’s state religion — though it would continue to influence thinkers such as Justus Lipsius, Baruch Spinoza, and Immanuel Kant — but its lengthy hibernation would lead to a surprising awakening around the middle of the 20th century.

Today, Stoicism is booming. Print sales of Aurelius’ Meditations, Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic, and all-things Epictetus’ are way up. The philosophy has become the subject du jour of newsletters, podcasts, Instagram feeds, self-help blogs, and quote devotionals proliferating the internet.

But what’s different about this modern Stoicism from its ancient counterpart? How can we separate the philosophy of life from the life hacks and quickie pop-Stoicism? And what, if anything, can Stoicism say about living a meaningful life in the modern world? I recently spoke* with Gregory Lopez, the founder of the New York City Stoics Meetup and cofounder of the Stoic Fellowship, and Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy at the City College of New York and author of How to Be a Stoic, to discuss these questions as well as explore the three disciplines of Stoicism.

Kevin: What brought you both to Stoicism? Considering how many schools of philosophy there are, why this one?

Greg: I would say luck played a role. I was practicing Buddhism in the early aughts, and it led me to volunteer for an organization that taught cognitive behavioral therapy to people with addictive behaviors. The cognitive therapy that they trained us in as group facilitators was called rational emotive behavior therapy. I learned that the founder of that therapy, Albert Ellis, was heavily influenced through Stoicism.

When I saw that philosophy could be practical for something, first of all, my mind was blown. I took a metaphysics class, and I thought philosophy was for constructing trilemmas about ontological issues. That you could actually use philosophy was crazy. That they were doing it 2,500 years ago, even crazier.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Greg: I looked around the internet and found very small groups of people trying to practice Stoicism, and so I decided to found New York City Stoics in 2013 as essentially a reading group. Then one day, Massimo came to the group, and our paths collided.

Massimo: I went through a pretty standard midlife crisis, both in terms of my life and academic career. I switched from biology to the philosophy of science, and since I was studying philosophy as a PhD student at the time, I thought that if there’s an answer available to life’s questions other than religious ones — which I had abandoned when I was a teenager — that has to come from philosophy.

So, I studied in a more-or-less systematic way. I began with Buddhism, but didn’t get very far because it just wasn’t speaking to me. From there, I zoomed into virtue ethics. I started with Aristotle; he didn’t speak to me. I moved on to Epicurius, and he did speak to me on several levels, but there were major things that I couldn’t go along with.

I was in this process of exploration when I saw a tweet that said, “Help us celebrate Stoic Week!” I thought, “What the hell is Stoic Week, and why would anybody want to celebrate it?” [Laughs.] Because at the time, I thought it meant the stiff-upper-lip, Mr. Spock type. Why would anybody want to do that? Then I realized the Stoics meant Marcus Aurelius, and I read The Meditations in college. The Stoics meant Seneca, and I had translated Seneca from the Latin in high school. I never thought they were actually talking about the same thing. So I gave it a try, and here we are a few years later.

Feeling like a new Stoic

Kevin: The title of your co-authored book is A Handbook for New Stoics. What is new about new Stoicism compared to the Stoicism of, say, Zeno, Seneca, and Epictetus?

Massimo: There is disagreement about what new Stoicism means perhaps predictably. Just like there was disagreement among the early Stoics. This is not a religion, and even if it were a religion, religious people disagree how to interpret their texts. Let alone philosophers.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Massimo: One of the authors that influenced me in recent years is Larry Becker, who wrote a book titled The New Stoicism. And Larry proposed a thought experiment: Let’s suppose that Stoicism continued past the 2nd century and responded to developments in philosophy and science throughout the centuries. What would that look like today?

My answer is that from the ethical perspective, it wouldn’t look very different. We would have essentially the same ethics (with some caveats). From the point of view of metaphysics, it would look somewhat differently. The early Stoics were materialists. They believed everything was made of stuff. But they also believed that the universe was a sentient being endowed with something called the logos, and that wouldn’t stand with our modern understanding of what the universe is like. So the Stoics would have updated that.

In fact, they were very open to change as long as new information came about. One example is that the early Stoics thought the control center of what we’d call the mind was the heart. Then later on, anatomists discovered it was probably the brain. So, the Stoics said, “Okay, it’s the brain. We’ll go with the facts and not a priori knowledge.”

Finally, there is logic. The Stoics were good logicians, very practical. And I think they would take on board everything that’s coming out of cognitive and behavioral science. Things like cognitive biases research. All of that could easily be incorporated into the system and updated. I’m curious to hear Greg’s answer.

Man is disturbed not by things, but by the views he takes of them.

Epictetus

Greg: I would point out that the book’s title is also a double entendre. It’s new Stoicism for people who are not currently practicing and to answer the question of what a modern kind of Stoicism would be.

Kevin: I see.

Greg: Overall, I believe that the modern Stoics can and should update their core ethics from the facts of how the world seems to work to us now. And the Stoics had several metaphors for how the three parts of theoretical philosophy interrelate.

My favorite is that of a field where logic is the fence to keep the animals out. Physics is the soil from which ethics, the crop, actually grows. So, you want to harvest the ethics, but what to do with one’s life depends on the kind of world we live in and the kind of beings we are. How we figure that out best is through the protection of good reasoning and logic.

I think that leads to some different conclusions from the ancient Stoics. We don’t believe the soul is a mix of fire and air, nor should we. We’ve moved on from that. But we can keep the spirit of Stoicism alive while adjusting beliefs and facts based on a modern understanding.

Massimo: One more thing: This isn’t just about the Stoics. Every other philosophy or religion has updated itself over the centuries. It’s just that normally if you’re talking about Buddhism or Christianity, the process has been so slow and so piecemeal that you almost don’t realize it. But it’s not like somebody is a Christian today in the same way they were 2,000 years ago. No matter what they profess, they don’t actually believe the same things. And rightly so. In the case of Stoicism, it’s a little more jarring only because there is no analogous continuity. Otherwise, it’s pretty much the same scenario.

The fundamental rule of life

Kevin: Good point. One more question to lay the groundwork: What is the dichotomy of control? You call it the central concept in Stoicism, and the book’s subtitle — Thriving in a World Out of Your Control — points to its importance. What do our readers need to know about it to better understand Stoicism?

Greg: The biggest thing is that it’s easily misunderstood and misapplied.

Massimo: [Laughs.] Yep.

Greg: The Greek is not saying things are in your control and things aren’t. It’s actually what’s up to you and what’s not. What can you actually choose to do as opposed to what’s happening or what’s the outcome? That’s the most important thing.

I would also add a couple of ways of misunderstanding it or abusing it. If people simply focus on the dichotomy of control as the be-all-end-all of Stoicism, they’re cutting Stoicism short because it falls firmly within the first discipline of Epictetus, which is the discipline of desire. That’s only the first step. You then move on to the discipline of action, which is how to become a good person. If you don’t add that second step, then you’re losing half or even more of Stoicism.

Massimo: I agree. Recently, I have made a point of not using the phrase “dichotomy of control” because it is open to people saying, “It’s not just the things I control and can’t control, but there are also things I can influence.” Yes, yes, I know. That is why it’s not about control. Pierre Hardot, the French scholar that arguably did the most in the 1990s to bring back the whole notion of a practical philosophy of life, actually refers to it as “the fundamental rule of life.”

Another thing, as Greg pointed out, is that too many people focus on the fundamental rule as though it were encapsulating Stoicism. But too much focus on the fundamental rule is what separates a philosophy of life from what I — derisively, I admit — refer to as life hackery. Stoicism is used to some extent as a set of life hacks. You want to make money and have a successful business? Use Stoic techniques. You want to be famous? You want people to fall in love with you? Stoic techniques.

That’s not what it is. In fact, it’s kind of the opposite. Stoicism teaches you that being successful, making money, having people fall in love with you, and stuff like that is not really what life is about. Those are preferred things if they come, and if they don’t, it’s okay.

It’s like saying that you are a Buddhist just because you meditate to calm yourself down. You’re not. You are a Buddhist if you accept the Four Noble Truths and follow the Eightfold Path. [Similarly], just because you repeat the dichotomy of control as a mantra, that doesn’t make you a Stoic.

If people simply focus on the dichotomy of control as the be-all-end-all of Stoicism, they’re cutting Stoicism short.

Greg Lopez

Greg: A quick example: Let’s say we live in a world where a manchild bought a social media company for some reason. I know it’s crazy, but let’s roll with it. Then he wants to fire a whole bunch of his staff at like three in the morning, and he gets a little worried. He thinks, “They could yell at me. They could cry. Then again, their reactions aren’t up to me, so I’m going to fire them all anyway.” That would be an abuse of the dichotomy of control.

The dichotomy of control would show that what’s actually up to him is being a good person. He can reconsider the effect he’s having on his employees and their lives. He can show compassion and find a balance where everybody is better off.

Massimo: [Laughs.] You picked a really crazy example.

Greg: I know. I’m sorry for being so out there.

Kevin: [Laughs.] I like a good thought experiment, but let’s keep it in the realm of reality.

Massimo: [Laughs.] That’s right!

Kevin: You tackled one criticism of the dichotomy of control: the misconception that it ignores the things we can influence but not control. Another one I often hear is that it makes us passive and indifferent to the world — a small S “stoic.” Greg, your out-of-left-field example touched on that one, but could we dig a little deeper?

Massimo: That is a common misunderstanding — like Stoicism essentially turns you into a doormat. In fact, a friend of mine refers to this as Doormatism instead of Stoicism.

And it doesn’t. The reason should be clear if one pays attention to what the dichotomy of control actually tells them. The notion is to focus where your agency lies, which is in making decisions. At the same time, because most people are adults — except for that hypothetical billionaire perhaps — we don’t throw tantrums if things don’t go our way. We make the best effort if we think it is the ethical thing to do, but we are ready to accept that sometimes we win and sometimes we lose. Sometimes our actions will achieve the effect we want and sometimes they won’t. We have to be okay with that because there is nothing else that anyone can do about it.

The discipline of desire

Kevin: [Laughs.] Speaking of tantrums, I think that lines up nicely with the discipline of desire — or, rather, it’s opposite. How should we understand “desire” from a Stoic perspective?

Greg: In short, a desire is just something you want positively in your life, and an aversion is something you want out of your life. They are your goals, what you want to achieve and avoid. That’s all. According to Epictitus, those are one of the few things that are completely up to us.

Kevin: Gotcha.

Massimo: Unfortunately, the misunderstanding often arises from the fact that the word desire in English has a number of meanings. For instance, some people come to me and say, “Well, I don’t control my desires. If I feel like having an ice cream, I don’t control that.”

But that’s not what we’re talking about. Having an ice cream is not your goal. It’s just a drive that you have. Your judgment can come in and say, “Wait a minute. It’s almost dinnertime. If I have an ice cream now, I’m going to spoil my appetite.” That means that you’re capable through the discipline of your desires to override that feeling and realize it’s not in line with your goals.

Kevin: I think another place where different meanings can muck up the message is in the word passions. What are we talking about when we use the word passion as a Stoic sense versus just using it in everyday life?

Greg: This gets back to the idea that Stoics should be completely flat emotionally and should be doormats. That’s not what the Stoics are talking about when they say passion. It’s not a history of people just sitting around until they die. A passion [in the Stoic sense] is a subset of emotions that are extremely unhealthy, and they are unhealthy for two reasons.

The first is they set reason aside; they rationalize for us. For instance, if you are angry at somebody, you’ll make up an excuse to get back at that person. Whether those excuses are valid or not, that passion takes over reason. Well, one of the core things that makes us human is reasoning, so anything that puts reason to the side literally makes us less human.

The second thing is that humans do better when we work together. We are hairless apes with crappy claws and barely any fur. Put a person in a forest on their own, they’ll probably die. So, we’ve developed social networks to help us thrive. But our passions put that to the side as well. An example is greed. If you want something material from someone else and you’re willing to hurt others to get it, that is anti-social. Again, it literally makes you less human.

Massimo: Unfortunately, the word passion tends to have a positive connotation in modern society. You’re passionate about something, and that’s a good thing. It’s another place where the Stoics run into a PR problem.

The flip side of that is, as Greg mentioned, that there are some emotions the Stoics see as healthy and therefore in need of cultivation. That gets you out of the stereotype of the unemotional Stoic. Yes, anger is an unhealthy emotion, and you should learn to deal with it. But love for your partner, your children, your friends, that’s a positive emotion. Why? Because it’s aligned with reason. Reason tells you that because you are a social being, you need positive relationships with other people. It’s good for you; it’s good for other people.

Kevin: I recently interviewed Dacher Keltner, and we talked about emotions. He mentioned how an emotion is a cognitive state that pushes you to behavior to bring about a change. To bring that into what you said, the state is still there. It’s the behavior that makes a practicing Stoic.

Massimo: Yeah. It is perfectly in line with what we know from modern cognitive science. Cognitive science tells you that you don’t have a choice about feeling this craving or that. What you do have a choice is where you act or not. You can exercise your willpower — not at the level of the craving but at prioritizing how you act on it.

Kevin: One thing I love about the book is that it has exercises to help readers practice these Stoic principles. As Epictetus wrote: “If you didn’t learn these things in order to demonstrate them in practice, what did you learn them for?” In that spirit, I’d like to ask a practical question about the discipline of desire, and I’ll draw on an example from my own life — one I’m sure you’ll recognize as writers.

When I’m drafting, my writing is never as good as the Platonic version of the article that lives in my head. What actually gets on the page is frustratingly lacking. That can lead to feelings of frustration and even anger. What would a Stoic do in this situation to produce a better outcome?

Massimo: I don’t know what you’re talking about. My drafts are always Platonic.

Greg: [Laughs.] Mine too. There must be something wrong with you, Kevin.

Kevin: [Laughs.] Guess it’s time to polish up the resume.

Greg: There are lots of possible exercises, but one is to premeditate on it so you get used to it. When you sit down, just take 30 seconds to visualize that after several hours, the draft will likely be terrible. The worst possible draft. Make it crystal clear in your mind and sit with that feeling. Then go draft anyway. It either will not be as bad as you visualized, in which case you’ll be pleasantly surprised, or it is and you knew it could happen.

The outcome wasn’t up to you. You put in the effort. Now think about what you can do going forward.

Massimo: Another way is going back to the fundamental rule. I know from the beginning that I want to produce a great draft that will be published as is. I also understand that it’s exceedingly unlikely. I’m probably going to fail at that.

The next question is, “What is up to me here, and what is not up to me?” Well, I can work on a good outline. It’s still up to me to go back and modify it. Maybe I can send it to some friends or colleagues and accept their suggestions with an open mind. However, the quality of the final draft is the result of my abilities, and I don’t control my abilities. All I control is my effort to make it better. At some point, I have to say, “Okay, this is the best I can do. This is the reality of things. I’m not the best writer in the world, but I’m good enough to get published.”

Kevin: That’s an interesting way to look at it. I get that the effort is up to me, but not the quality of the final draft? That feels very counterintuitive.

Massimo: From a Stoic perspective, it is the same criteria you attach to an analysis of every situation. If you are a soccer player, you realize that the outcome of the game is not up to you. What is up to you is to play the best game you can. If you are a musician — an example that Epictetus uses in The Discourses — it’s up to you to try your best to play well. Whether the audience is going to be pleased or not is for them to decide. It doesn’t fall under your preview.

Greg: The fact that you called it counterintuitive is what the Stoics would call an impression. You can do what Epictetus advises and say, “Stop. You’re just an impression and may not be what you claim. Let’s analyze that.”

A possible exercise would be listing out the reasons why it feels counterintuitive. Make them explicit and then challenge them with an open mind. Force some counterexamples. Ask why that would be the case? Maybe the impression is correct, maybe it’s not. Laying it all out on paper could be a useful way to tune your intuition.

The discipline of action

Kevin: I’ll try that.

Let’s move on to the discipline of action. I think this goes back to what we were discussing earlier — both in the sense that we need to take these actions into our lives but also how they are socially bound. Can you talk about that?

Greg: I would say the discipline of action has two goals. The first is to act intentionally and not have knee-jerk reactions to the things around you. Then if something warrants action, try not to harm others. Do it prosocially. Take others’ viewpoints and wellbeing into account. That’s it in a nutshell.

Massimo: Ethically, the discipline of action is, to some extent, informed by the historic notion of cosmopolitanism. You want to act prosocially with everybody. Whether they are your friends, relationships, or live on the other side of the world, it doesn’t matter. I think one of the things people underestimate, even those who practice Stoicism, is cosmopolitanism. It’s a fundamental idea in Stoicism that informs the entire story. (It’s not originally from the Stoics, it probably comes from the Cynics, but it’s very explicit in the Stoics.)

In fact, I would argue even that at some level, this is the step that transforms Stoicism from life hackery into a philosophy of life. If you have the techniques, that’s life hackery. But what are you using your techniques for? To make the human cosmopolis a better place for everybody? That is where you get to the ethics. That’s where you get a philosophy of life.

Kevin: I think social media is perhaps a good place to consider putting the discipline of action into action. Say you came across a social media post that upsets you. Maybe it’s factually inaccurate or the person’s tone is rude or he is making light of a serious situation. Whatever the reason, how can we respond to such a situation like a Stoic?

Massimo: Yeah, that happens to me all the time. In fact, last year, I did take the step of abscinding myself from social media for nine months. I just left Twitter and Facebook because I had to reflect on what the hell I was doing there. Then I came back essentially to try to renew my Stoic vows (so to speak).

What I do is, first of all, pick my battles. There is all sorts of stuff I can and should ignore because it’s clear it’s coming from somebody who is not ready to listen and actually engage. I just leave those alone. Then it’s an effort of self-control. One of the four cardinal virtues of Stoicism is temperance. So, trying to figure out when it is that I need to act and when not. That’s part of Stoic practice.

When I do engage, I try my best. So instead of calling somebody an idiot, which sometimes comes right to my fingertips, I’ll instead ask a question. Why exactly do you believe that? Where does that come from? That again comes from the fundamental rule, convincing somebody else is not up to you. What is up to me is to put out the best arguments, the best sources, and the best approach I can think of in terms of having a conversation with others.

If you have the techniques, that’s life hackery. But what are you using your techniques for? To make the human cosmopolis a better place for everybody? That is where you get to the ethics. That’s where you get a philosophy of life.

Massimo Pigliucci

Greg: A couple things to underpin what Massimo mentioned: First, do it with intention. If you feel a knee-jerk reaction, perhaps park it in a tab and walk away for an hour. The world’s not going to end within that hour.

There is also a question of how effective you’re being. Epictetus’s nuanced version of the discipline of action involves role ethics and taking into account who you are in relation to the situation. Two different people within certain groups can be in the same situation, and it would be the correct answer for one of them to respond to the tweet and the other to not. For instance, [during the COVID-19 pandemic], I saw virologists and epidemiologists chime in on misinformation because they are well-informed. So, we have somebody who knows what they’re talking about. Should a Stoic philosopher chime in? Probably not, if that’s not their area of expertise.

So, who are you in relation to the thing that’s going on? It’s a complicated thing to think about, but will give you pause and allow you to act intentionally.

The discipline of assent

Kevin: Okay, let’s wrap up with the discipline of assent. I’ll be honest: This one was trickier for me to wrap my head around. It felt like it was more of the previous two disciplines. What separates the discipline of assent from the other two?

Greg: The discipline of assent is doing the previous two disciplines, acting well and taming your desires. It is about looking at your thoughts as they come up and acting quickly and a lot more consistently — cutting things close to the root. That’s all it is. It’s the same as the previous two, just more rigorous.

Massimo: I agree. I would say Epictetus is concerned with two things: realigning our desires and acting in the world in ways that are in agreement with reason. Then the third discipline is how to do those two things better. Ideally, he says, automatically.

An analogy I often use is learning to drive a car. Initially, it’s kind of nerve-wracking because you have to pay attention to everything. There are the pedals and shifting gears and the pedestrians in front of you and the other cars around you. You’re slower to react because you’re not confident in what to do. It requires effort and time.

But if you keep practicing, it all becomes second nature. You are going to get to the point where you can have a conversation with somebody else in the car and keep track of everything else. You don’t even realize it. I think that is what the discipline of assent is trying to do, which is why Epictetus says it’s the most difficult one.

It takes effort, and you might not get there by the end of your life. It’s continuous, but it gets better and better and better.

Kevin: That’s a great analogy.

Final question: You both came to Stoicism. You’ve learned from it, and practiced it. How do you feel it has changed your life for the better?

Greg: The main thing that I got out of Stoicism, and why I kind of combined it with Buddhist practice, is because of the discipline of action. I’m naturally an introvert and don’t want to go out into the world a whole lot. But I’ve become politically active in a certain cause, and I think I can have an impact. I attribute that to actively practicing Stoicism.

I also co-founded a nonprofit Stoic fellowship to try to grow local Stoic groups around the world, and I may not have done that had it not been for Stoicism. It does make my mental life harder, but that is also classically Stoic.

Massimo: In my case, my practice has been largely focused on what people describe as Epictetus’s “role ethics.” So, I am much more cognizant, and hopefully thoughtful, about my roles in life: the role of a father, the role of a husband, of a teacher, a colleague, and so on. I pay much more attention to what these roles entail and how to best play them. I’ve certainly not perfected it, but I’ve improved. It’s far more focused and present in my mind.

I also have received incredible feedback from people. I regularly get people writing to me to say they read How to be a Stoic or A Handbook for New Stoics and how much it helped or, in some cases, even changed their life. I’ve been writing and teaching for most of my life at this point, but it’s only after I got into Stoicism that I got that kind of feedback. And it feels good to be able to do something that you feel is important. It reinforces my commitment to keep doing it.

Kevin: Thank you both for your time and for speaking with me. I learned a lot and found your book full of useful information and practices. I appreciate getting the opportunity to engage with it.

Massimo: You’re welcome. It was a pleasure, and good luck working through the rest of the book.

Greg: Yes, thank you, Kevin.

Kevin: Where can people find you online to learn more about Stoicism and your next projects?

Greg: I would plug the Stoic Fellowship (@StoicFellowship) if people want to start their own Stoic groups. I have a personal website, greglopez.me. If people want to contact me for any reason, they could reach out there. I’m also slowly making practical Stoic courses, and people can sign up for those when they’re available … within the next decade. [Laughs.] They can find those at stoicmissingpieces.com. The goal is to fill the holes in Stoic practice beyond the introductory material.

Massimo: People can find pretty much everything I do at massimopigliucci.org. Other than that, I am on Twitter @mpigliucci.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

* This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.