We need an “orbital perspective” to solve Earth’s problems

- The world faces many problems that seem like they have no solution.

- According to retired astronaut Ron Garan, the root of these problems is that we don’t see ourselves as planetary beings.

- By adopting an orbital perspective and recognizing how inextricably linked we are, we can better operate as one toward solving those problems.

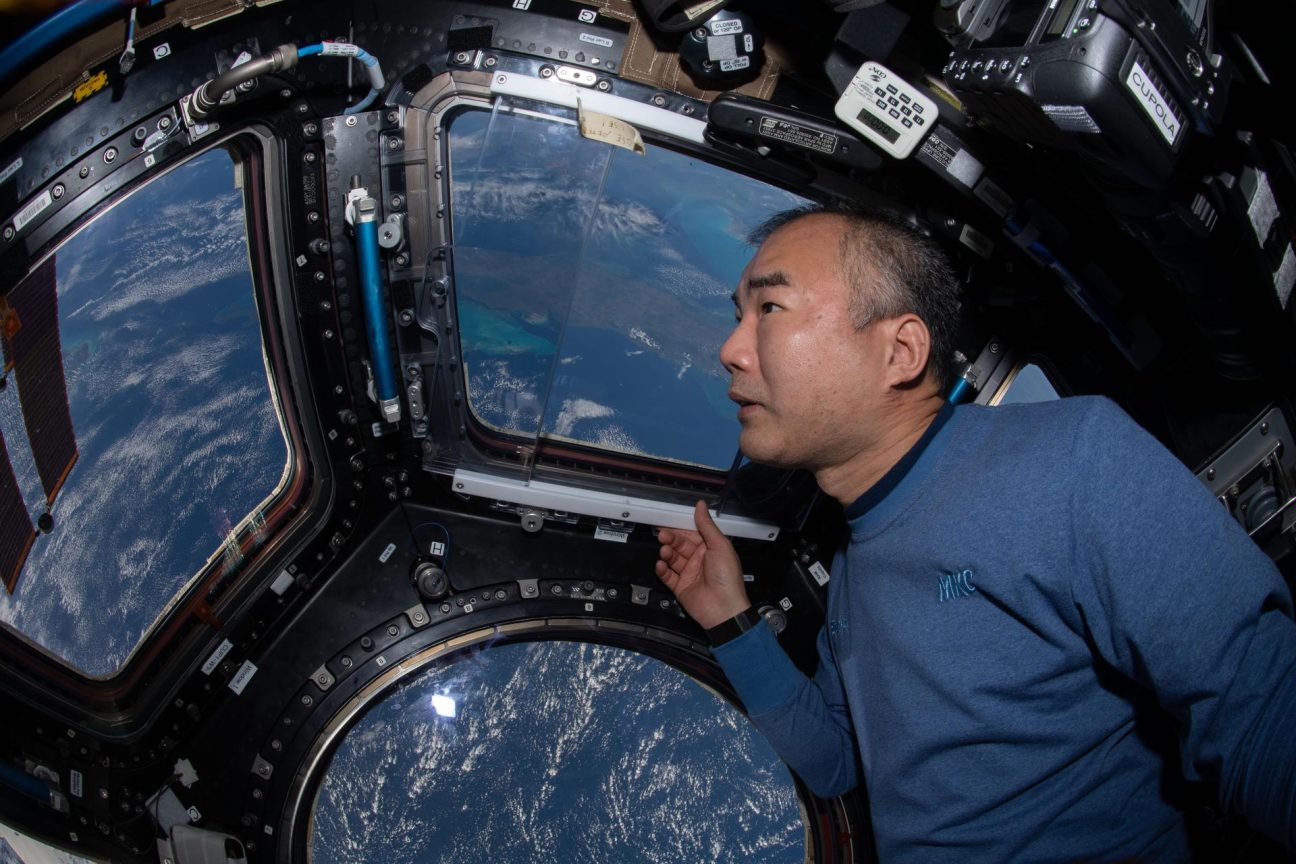

While aboard the International Space Station (ISS), Ron Garan was tasked with consolidating the contents of two toolboxes into one. From a terrestrial perspective, that may seem simple enough. But nothing is simple in space. Every procedure must be meticulously planned and accounted for.

Garan read through the “long, complex, and highly-choreographed” procedure and discovered that the tools weren’t in the starting positions assumed by its writers. Because of this, the task couldn’t be executed as planned, so he contacted the ground to request a change. (Everything must be accounted for in space).

As he spoke with the CapCom — a member of mission control who communicates with the astronauts in space as is typically an astronaut themselves — he found they were resentful of his request because so much effort and care had gone into drafting the procedure. Although he was ultimately given permission to revise the steps, it was clear from their “stern and somewhat disgusted tone” that they were unhappy with the compromise.

Recounting this experience on his podcast, Garan sees that it conferred a valuable lesson: “As I finished reconfiguring and consolidating the toolboxes, I realized that sometimes the common ground that is missing is a common starting position.”

Garan had one starting position: the tools as they were. Those at mission control had another: the tools as envisioned. When the facts didn’t match that perceived reality, rather than move to a new starting position, those on the ground altered the facts to fit their original perception.

For Garan, this lesson extends beyond the challenges of consolidating toolboxes in space. It stands at the heart of the global problems humanity faces today. The impasses impeding progress on poverty, refugee rights, deforestation, political strife, climate change, and the like arise because humanity lacks the proper starting position to recognize the facts on the ground.

“In reality, [these issues] are just symptoms of the underlying root problem,” Garan said in an interview, “and the problem is that we don’t see ourselves as planetary.”

The orbital perspetive

Orbiting the Earth, Garan witnessed massive thunderstorms, the Aurora Borealis, and the protective glow of Earth’s atmosphere. He didn’t see an economy, national borders, political divides, or other human-made phenomena that seem so omnipresent on the ground but are imperceivable from space.

Garan isn’t alone. Many astronauts have reported that when seeing Earth from space, a profound sense of awe and transcendence overtook them. They felt their personal boundaries break down and a swelling sense of interconnectedness to their home and the people living there. This perceptive change is popularly known as the “overview effect.”

As retired astronaut Leland Melvin described the sensation: “I got this cognitive shift that I felt — looking at the planet with no borders and one race, the human race. When I got home, it made me feel so much more connected with everyone around me. Whether it’s someone in this tribe or that tribe, I felt that we had a common purpose to help keep our humanity going forward.”

But experiencing the overview effect would be more than a kumbaya moment for Garan. It became a call to action that he calls the “orbital perspective.” Once people see the “interrelated structure of all reality,” he contends, then we can put aside our differences and reach a common starting position where the facts align, and we can see the problems for what they really are.

We are not from Earth; we are of Earth.

– Ron Garan

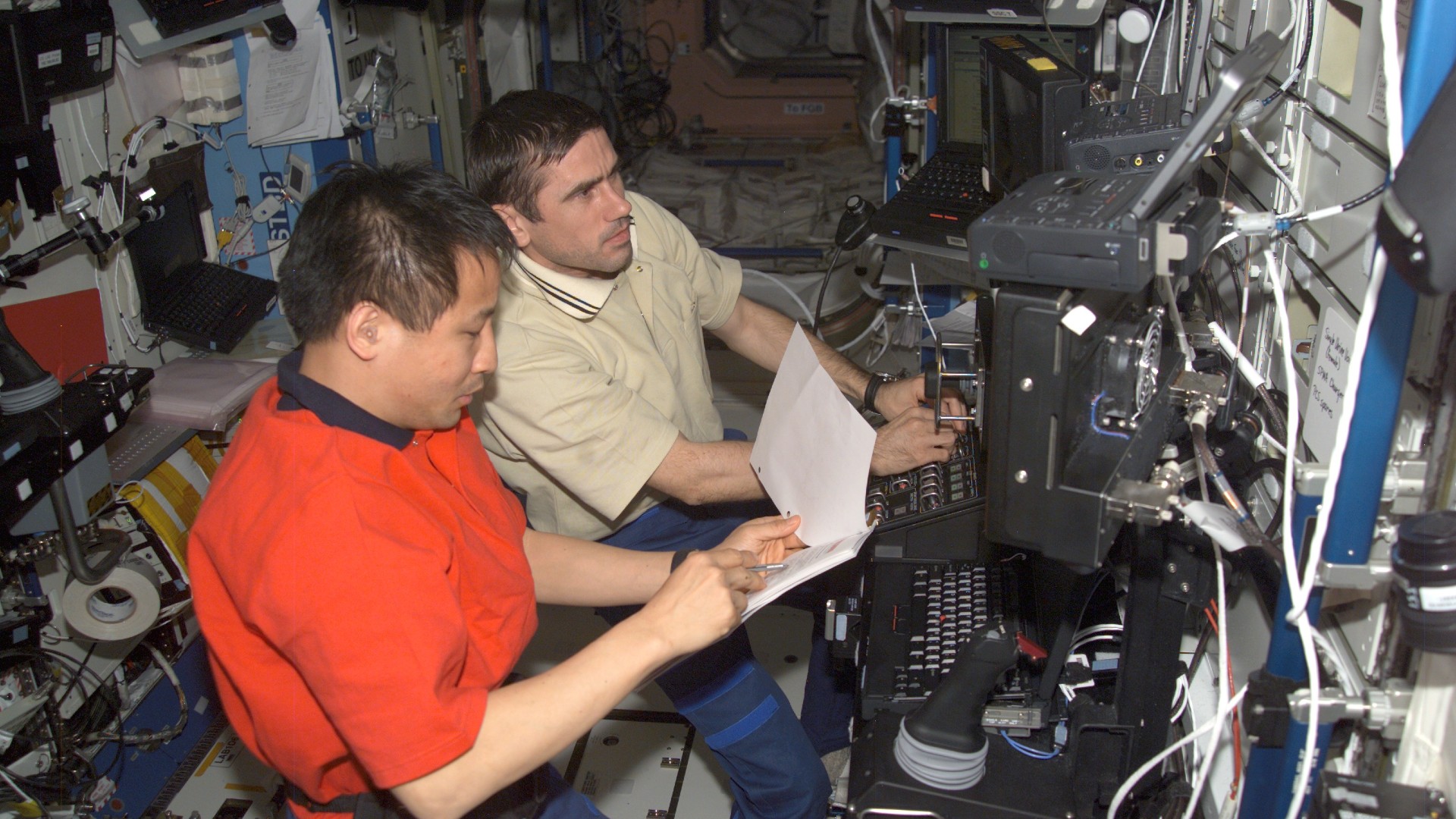

ISS: An exercise in international cooperation

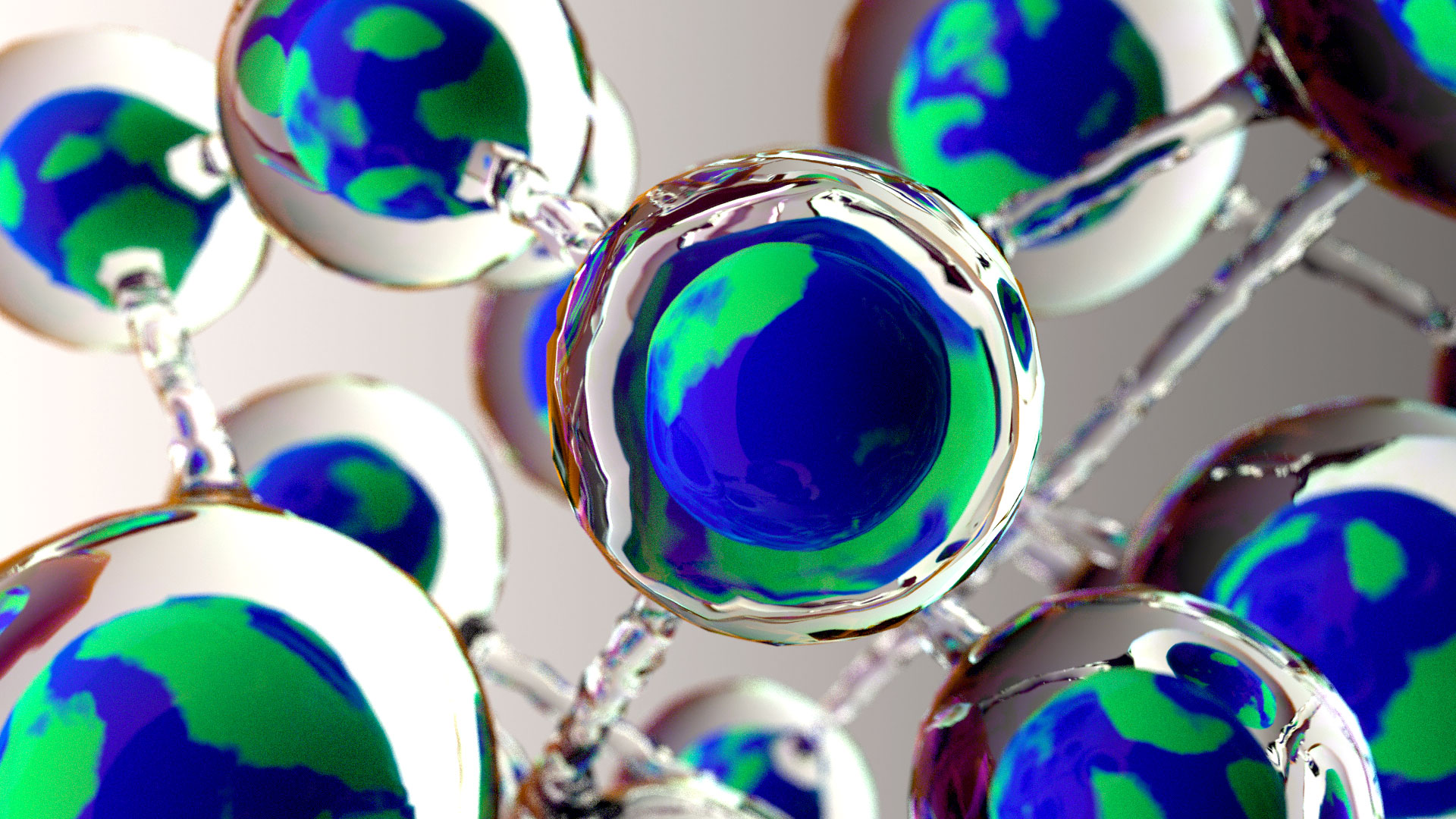

To see the orbital perspective in action, we need only consider the ISS itself. Today, the station has become an icon for international cooperation and humanity’s enterprising spirit. But that almost wasn’t the case.

In 1984, President Ronal Reagan directed NASA to develop a permanently crewed space station to reestablish America’s superiority in space and over the Soviet Union. While the Soviet Union beat NASA to the punch by launching the space station Mir in 1986, NASA pushed ahead with its plans to launch a space station called Freedom. Japan, Canada, and several European countries would also sign on to help design, construct, and operate within Freedom.

The stage was set for an extended space schism. Then the Soviet Union collapsed. Recognizing the opportunity, President Bill Clinton extended an invitation to Russia to join the international space station venture — and Freedom became a project of truly international scope.

Russia brought years of experience operating a space station in low orbit to the partnership. It also added modules originally planned for Mir-2 and trained U.S. astronauts aboard the original Mir before its deorbit in 2001. In return, Roscosmos received the funding and support the space agency desperately needed amid the country’s devastating post-Soviet depression.

Now, more than 20 years after the first crew boarded, the ISS has housed more than 200 people from 19 different countries. Its facilities have run thousands of investigations in fields such as biology, physical science, technology development, and human research for more than 100 countries. Those endeavors have expanded our scientific knowledge and produced research that will be key in solving medical and social challenges on Earth — insights that are the patrimony for all of humanity.

Thanks to the relationships and trust built through those experiences, Garan notes on his podcast, the ISS has continued its planetary mission. Onboard, there isn’t a Russian crew and an American crew trying to outcompete each other. There’s a single crew working toward their goals together.

“Following that example, we need to operate as one international, unified crew here on the surface of spaceship Earth,” Garan said. “The very ingenuity and cooperative nature of humanity should give us hope that we can build this future.”

Finding an orbital perspective from the ground

Of course, few people have jobs aboard the ISS. Fewer still can ask Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk to hitch a ride on their next launch so they can try the overview effect for themselves. Thankfully, neither is required to nurture the orbital perspective in your life.

“You don’t have to go to orbit to have the orbital perspective,” Garan says.

One tool we have for cultivating an orbital perspective is awe. While the research into awe is fairly new, it suggests that awe-inspiring experiences boost our mood, decrease materialism, increase humility, and help people better integrate into social collectives.

For an experience to be awe-inspiring, it must have two features: first, a sense of vastness, and second, it must lead a person to reevaluate their ideas and beliefs in light of that experience. Such experiences are readily available on Earth. We can find them in natural wonders, masterworks of art, human achievements, or by simply noticing the intricate, yet often overlooked, beauty and detail in the world around us.

Another tool is what Garan calls the “dolly zoom,” a term he borrowed from cinematography.

When preparing a dolly-zoom shot, a cinematographer will fix their camera with a wide-angle lens — allowing them to capture as much of the scene as possible — and attach it to a dolly — basically, a wheeled camera cart. As the camera is pulled back on the dolly, the cinematographer zooms in on the subject. This method creates a field-of-view illusion where the foregrounded subject stays the same size while the background squeezes to reveal more within the frame.

By dolly zooming on a problem — whether that’s an international concern, a local issue, or a challenge in our lives — we widen our perspective to encompass the widest possible framing of time and space while also keeping the individual details in focus. This approach taps into the orbital perspective by keeping the big picture in mind and maintaining a human connection with the people whose lives will be affected. This prevents us from seeing either as impersonal abstractions.

When people with different perspectives agree to engage with that scope as their starting position, together, they can make better decisions, develop more accurate opinions, and begin working toward more holistic resolutions to the problems they face.

As Garan said: “In the long term, I’m very optimistic because I do see a blossoming unity spreading across our planet. A blossoming awareness of our interdependent nature. That awareness will eventually hit critical mass, and when it reaches critical mass, then we’ll be able to solve the problems facing our planet.”

(And consolidate toolboxes with a little less bickering.)

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.