Humility: Why modern leaders need to resurrect this ancient virtue

- The U.S. is suffering an epidemic of narcissism, fueling a rise in loneliness and despair.

- Empirical evidence supports what ancient wisdom declared — that humility is transformational and beneficial.

- To cultivate humility in your life, pursue honest feedback and develop your empathy.

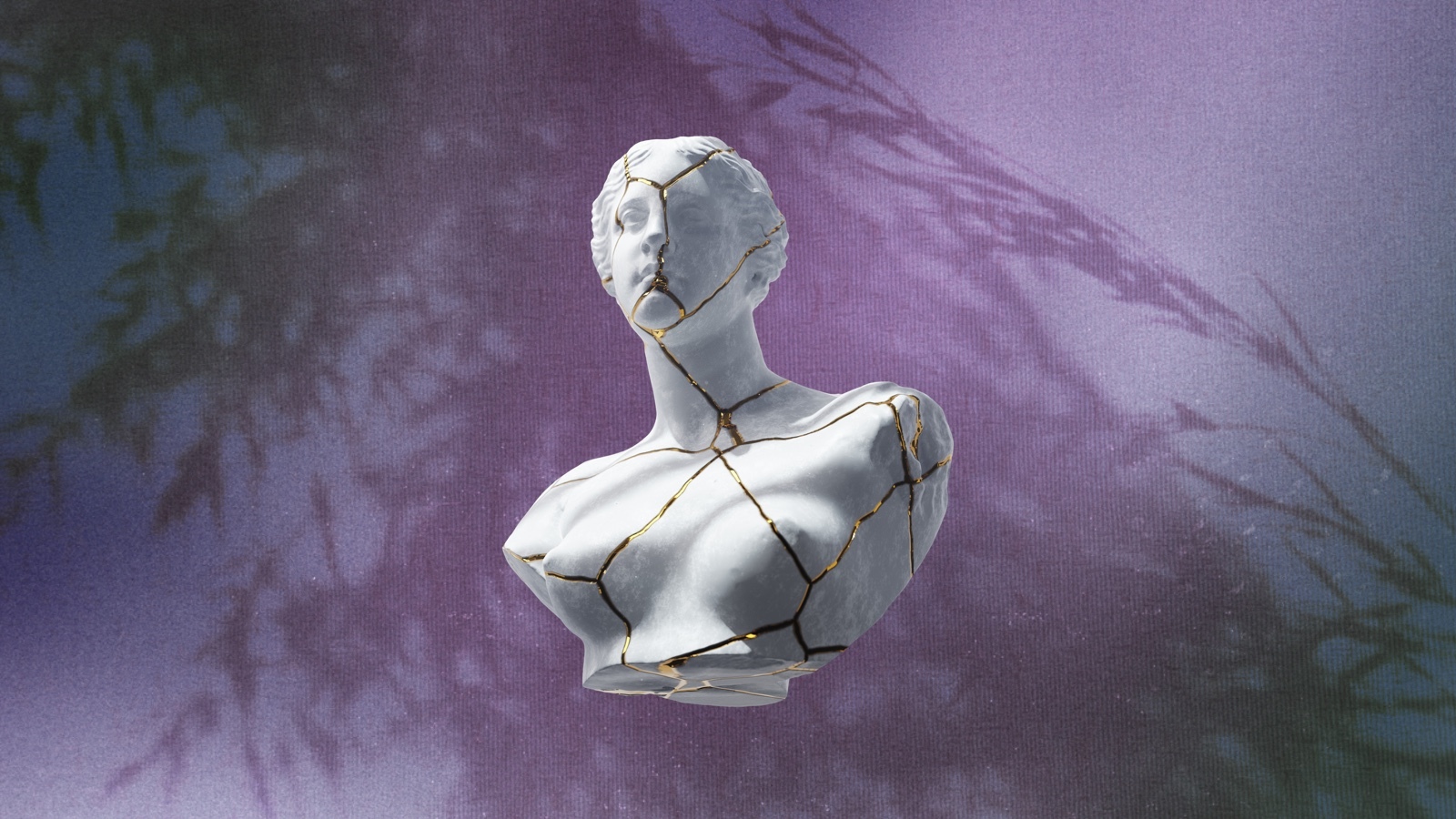

Many ancient thinkers have written about the dangers of arrogance. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius warned against losing one’s modesty in The Meditations. Saint Augustine called pride the “origin of evil” in The City of God. Confucius said, “A superior man is modest in his speech but exceeds in his actions” in The Analects. Finally, the classic: “Pride goeth before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall.” Proverbs 16:18.

And yet, history remembers the greats and the conquerors, not the meek or the mild. CEOs and celebrities become icons for their charisma and grand lifestyles. Even ordinary people have become locked in a spiral of one-upmanship — endlessly outdoing each other with larger houses, sportier cars, and more luxurious vacation photos clogging up social media feeds.

Is humility truly a virtue, or were the ancients as wrong about it as they were witches and dragons living on the edges of the map?

To find out, we spoke with Daryl Van Tongeren, an associate professor of psychology at Hope College and the author of Humble. During our conversation, we discussed why humility seems in short supply, the value it brings, and how we can better cultivate it in our lives.

Big Think: Why write a book on humility now?

Van Tongeren: I’m certainly not the first person to think that humility is a good idea, but two things have happened.

First, we’ve accumulated enough psychological research to have a clear sense of what ancient wisdom has suggested for a long time. The empirical data support that humility really is transformational.

Second, our culture — particularly in the United States but also worldwide — needs it more than ever. The U.S. is in the midst of what scholars have called a narcissism epidemic. Our overinflated sense of self is growing at astronomical rates. We’re seeing this lack of humility in political, religious, and other cultural conflicts that are creating a sense of despair, loneliness, and mental disease that we perhaps haven’t seen in quite some time.

Big Think: The word epidemic suggests that things have worsened from the past. How do we know that change has taken place?

Van Tongeren: Jean Twenge, Keith Campbell, and others have tracked Narcissistic Personality Inventory scores over the past 40 years. What they’ve seen is those scores increasing. People are self-reporting greater levels of narcissism relative to what they did in the past. The researchers have also looked at other measures — like the size of houses — that might indicate people demonstrating superiority or a sense of entitlement.

What I think we’re experiencing now is a society where our self-worth and self-value are linked to external contingencies. We don’t think we’re enough unless our bank account is enough or we have enough followers or we take enough interesting vacations. A lot of people are blaming social media for this, but it might just be putting a magnifying glass on a social comparison that has been accelerating for some time.

How should we define humility?

Big Think: Humility is a word with a lot of associations attached to it. What are we talking about when we talk of humility?

Van Tongeren: I think about humility in two ways. One way is being the right size in a given situation — not too big, not too small. Many of us are aware of the problems of arrogance and being too big. You’re not listening, not valuing other people’s perspectives, and so on. But the other side is being too small. For example, I don’t want a brain surgeon to ask me what surgical techniques I recommend. No way! I’m paying for a brain surgeon who is appropriately confident in that situation.

The other way of thinking about humility is our ability to know ourselves, check ourselves, and go beyond ourselves. This way starts with self-awareness and an accurate assessment of one’s strengths and weaknesses. Then it requires restraining those selfish impulses while also considering other people’s needs and well-being as equal to your own.

The state of humility

Big Think: How can we better know ourselves? If you ask yourself, “How humble am I?” and your answer is, “Super humble,” then are you really all that humble?

Van Tongeren: You’re highlighting two things. First, how do we figure out how humble we are? I think that asking a trusted source is probably a good way of getting an initial assessment. I have studied humility for years, and I thought I was humble. Then I asked my wife to rate my humility, and she disabused me of that delusion pretty quickly, which I’m grateful for. [Laughs.]

Then the second point: How do we assess humility? In the beginning, researchers were stymied because we thought you couldn’t just ask someone. A really humble person may give you a high score but a really arrogant person might too.

So some colleagues and I developed this other report measure. What we do is assess a person across relationships. How do most people view this person’s [humility]? Over time, we got a good assessment by triangulating these reports with self-reports.

This is also a good reminder that relationship to relationship, sometimes even moment to moment, our humility can change. We might even consider humility as a kind of state or experience. Maybe you’re very humble at home but at work you’re a total jerk. The most humble people are the ones who can cultivate these states and experiences over time and across relationships.

The research shows that humble leaders are much more effective. They are more likely to make suggestions, and their teams are more creative, healthier, and have higher productivity.

The benefits of humility

Big Think: What are the advantages of being humble in our lives — especially when it seems like the least humble among us are getting the attention, the money, and the likes?

Van Tongeren: Being arrogant or narcissistic may pay off in the short term, but that’s certainly not the case in the middle-to-long term.

What we find is that humility has significant benefits relationally. People are more likely to be satisfied, committed, and forgiving in a relationship with a humble partner.

We also see a lot of benefits at work. A lot of people think that only narcissistic, hard-driving leaders get things done. But the research shows that humble leaders are much more effective. They are more likely to make suggestions, and their teams are more creative, healthier, and have higher productivity. In fact, those teams are likely to be humble as well, so humility is a bit contagious.

The third place is in areas of conflict or where there are ideological differences. A truly humble person will acknowledge that their way of life or of seeing the world is not the only way. They take a posture of learning and curiosity. They want to learn from people who view the world differently.

Big Think: You write in your book: “Humility is a way of approaching ourselves, other people, and the world around us with a sense of enoughness — an unconditional worth and value — that opens us to the world as it is.”

How do we balance that sense of unconditional worth with the need to improve and learn?

Van Tongeren: The desire to grow and learn should be intrinsically motivated. It shouldn’t come from a sense that you have to improve because you’re deficient in some way.

That’s a kind of freedom I think that humility can offer people. I took up running 12 years ago, and I’m not fast. I’m a plodder who is never going to qualify for Boston. But I love it. It’s therapeutic for me. I also make hot sauce. I’m never going to have my own brand or make money at it, but it’s something I enjoy.

Humility helps us disentangle from approval, acceptance, and status and just enjoy the pure luxuriousness of doing something that we enjoy.

4 ways to cultivate humility

Big Think: What are some things we can do to cultivate more humility in our lives?

Van Tongeren: One thing you can do is get feedback. You need to ask a trusted source, someone who knows you in different capacities and whose opinion you trust. It also shouldn’t be someone who will be ingratiating towards you or someone who will be spiteful. A good friend, a family member, or a romantic partner is usually in a good position to assess your humility.

Then try hard to not be defensive. That’s what I did [when I asked my wife]. I got super defensive because that’s kind of our default as human beings. But there’s often an opportunity to pause and ask yourself, “How could I be wrong? If this person is right, what would that mean?”

I also recommend cultivating a sense of empathy. Empathy is both the cognitive appreciation of someone else’s perspective as well as the emotional attunement to what they are feeling. If you can make that head-to-heart connection, it might be the single most important thing we can do to cultivate humility.

Finally, it takes practice. Every day, we wake up, and we get on the moving walkway toward narcissism. Our culture is pushing us towards self-aggrandizement, and if we’re not walking against that, we’ll naturally end up there. But over time, that practice becomes a little more routine, and we start seeing the benefits of humility in our lives.

Humility is just one virtue in our toolkit, and we need to develop the wisdom to figure out when to use it.

Big Think: How can we look at humility in the context of other virtues?

Van Tongeren: I think that humility is one of many virtues that we can develop, and while I think humility is important for our cultural moment, I don’t think that it will solve all of our problems in isolation. There are times when courage or justice might be better virtues to call on. They may be more likely to bring about change and defend the rights of people who are facing harm. Humility is just one virtue in our toolkit, and we need to develop the wisdom to figure out when to use it.

Big Think: Where can people find you if they want to learn more about humility and the work you’re doing?

Van Tongeren: My website is darylvantongeren.com. On X, I’m @drvantongeren, and on Instagram, I’m @darylvantongeren.