5 philosophy books that shaped Chinese thought

- China boasts over 4,000 years of continuous history and a rich philosophical tradition.

- These five texts provided the foundation for some of the most interesting developments in philosophy.

- From Sun Tzu's Art of War to Confucius' Analects, the ideas in these texts have over time managed to resonate with a global audience.

China is the cradle of the world’s most ancient continuous civilization. Boasting over 4,000 years of documented history, Chinese thought and philosophy offer a wealth of insights. Luckily for us, as in Western philosophy, a few key texts have exerted influence over the rest. Here, we spotlight five texts that have shaped Chinese thought, and more recently gained an international audience.

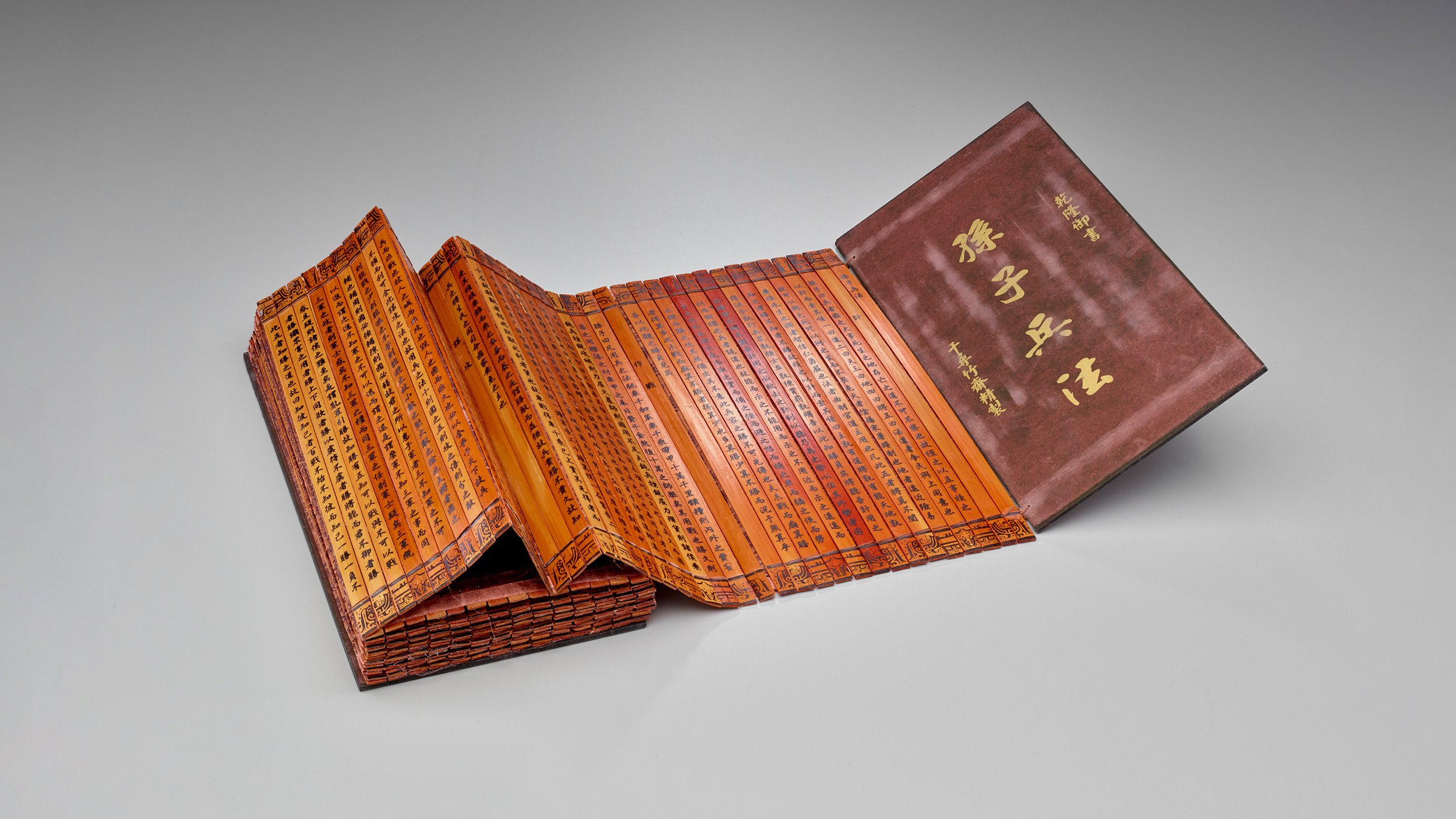

I Ching — Traditional

The I Ching, also known as The Book of Changes, dates back to the 10th century BCE. The author is unknown. However, some traditions name Fu Xi as the author of the first section and the Duke of Zhou as the author of the second. The author of the commentaries known as the Ten Wings is traditionally listed as Confucius.

Much of the I Ching is oriented toward divination. In traditional practices, diviners used a specific method involving yarrow stalks, where a series of selections and divisions of the stalks led to the determination of either a broken or unbroken line; a broken line signifies yin, while an unbroken line represents yang. Through this ritual, a sequence of six lines is generated, forming a hexagram. With 64 possible hexagrams in total, each conveys a distinct meaning and insight. (In contemporary practices, coin flips have become a more common alternative to the yarrow stalks for generating these lines.) The commentaries within the book posit that these hexagrams mirror the shifts in the cosmological cycles of the Universe.

It may seem strange to include a book on divination on a list of the most influential works in philosophy, but Chinese intellectuals have long considered the I Ching to be an important text. Han Dynasty scholars tried to sync their system of government to the cosmological system outlined in the text. Confucius referred to his copy so often it required regular upkeep. Zhu Xi argued that it could be used to give depth to moral questions that Confucian ethics could then answer. Its importance in political philosophy only ended with the 1911 revolution, which overthrew the dynastic system of government.

Its influence in the West is perhaps more interesting. The German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz argued it proved the universality of binary number systems and God’s existence. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel disagreed with him and argued against binary systems being able to express much of anything. More recently, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr borrowed from it when devising the principle of complementarity in quantum mechanics.

Tao Te Ching — Laozi

The Tao Te Ching is a foundational text in Taoism. It is traditionally credited to the semi-legendary Laozi. However, modern scholars increasingly believe it compiles existing ideas from early Taoism into a single text. A series of short, often seemingly paradoxical statements, it is an introduction to the Tao and a system of virtues.

While the Tao that can be spoken (or written) about is not the true Tao, I will still attempt to explain what the book describes here. The Tao is the fundamental nature underpinning all of reality. As Laozi puts it:

“Since before time and space were, the Tao is. It is beyond is and is not. How do I know this is true? I look inside myself and see.”

Laozi repeatedly praises emptiness as the source of creative power. This gives some meaning to his tendency to describe the Tao by what it is not. The book’s first half explores Tao, while the second focuses more on virtue. Both sections contain advice for rulers of ancient Chinese states.

Highly poetic, the text can be difficult to decipher and seems to purposefully encourage differing interpretations and understandings. Several points are generally agreed upon, however. Laozi praises the virtue of naturalness and encourages the reader to live in harmony with Tao. He also praises “Wu-Wei,” often translated as “effortless action.” At the individual level, it can be considered “not-forcing” and allows a person to understand the world more deeply.

China produced many schools of thought and Taoism is grouped with Buddhism and Confucianism as the three most influential. The key Taoist works were included on official lists of “classics” to be studied by anyone hoping to become a government official in imperial China. This was the case even when the other two schools were enjoying much more favor among the literati. As a religion, it boasts millions of self-identifying followers and nearly a billion more who practice some elements of the religion.

Beyond its influence on Taoism and other Chinese philosophical movements, it has affected Western thought. Most interestingly, anarchists and libertarians of all colors admire the book. Murray Rothbard called Laozi the first libertarian. Ursula Le Guin, a fan of left-wing anarchist thought, produced a new edition of the text and incorporated its ideas into her utopian fiction. Leo Tolstoy, an anarchist pacifist, also enjoyed Laozi’s work and expanded on it.

The Art of War — Sun Tzu

The Art of War is a treatise on military strategy attributed to the Chinese military general Sun Tzu. While his existence is still debated, he is reported to have been a general during the Spring and Autumn period, which lasted from about 770 to 481 BCE. The book attributed to him is undeniably one of the most important military texts ever composed.

The 13 chapters of the book cover different areas of military strategy, including preparing for battle, attacking, using spies, and the specific use cases of fire in combat. Of course, not every tidbit in the text is purely military strategy. Many of its ideas are applicable in other fields. For example, one of the most widely referenced bits is:

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

This has obvious applications in many other areas of life, from business to sports. The Taoist influence on Sun Tzu is highly evident here: He often uses Laozi’s style and seems to imply that a great general will have much in common with a well-practiced Taoist.

In addition to being a widely studied classic and a test subject for those taking military service tests in imperial China, the book is still considered a primer on strategic thought. Despite its age, it continues to influence modern warfare. American General Douglas McArthur kept a copy on his desk. General Võ Nguyên Giáp of the People’s Army of Vietnam applied its teachings in his victories over the French and Americans. The book is also allegedly a favorite of intelligence agents.

Analects — Confucius

Confucius is by far the most important philosopher in Chinese history and, by extension, one of the most influential philosophers in world history. Analects is a collection of his sayings and teachings gathered by his students, providing one of the best looks at the teaching style and wisdom of one of the greatest minds in the history of philosophy.

Like the Tao Te Ching, Analects consists of many short passages. Famously, many begin with the phrase “Confucius said” or “The master said,” depending on the translation. Much like Laozi’s work, Analects does not entirely consist of direct statements on what Confucius thinks is right or wrong but often includes short stories giving insights into his system of thought. For example, one section on the value of human life is phrased:

“The stable being burned down, when he (Confucius) was at court, on his return he said, ‘Has any man been hurt?’ He did not ask about the horses.”

His system of ethics centers around building up virtue (Ren) and becoming a “superior person” (Junzi). (Big Think has covered these ideas before.)

The influence of Confucius’ teachings cannot be overstated. While he claimed to be promoting existing ideas, the ideas he advanced eventually became canon. Anyone hoping to get a government job had to pass a civil service exam, an idea he refined, centered around his teachings and other related texts. Each book on this list was included at some point or another. Confucian thought, often viewed as a religious system named “Confucianism,” eventually became China’s leading system of thought. Some commentators have gone so far as to suggest that even modern Chinese communism is best viewed as Confucian thought with a red coat of paint.

In the West, his ideas first arrived during the early years of the Enlightenment. Both Voltaire and Leibniz were fans of his work. Voltaire considered his ideas on meritocratic government particularly revolutionary. The idea that civil servants should have to pass civics tests before taking office existed before Confucian thought arrived in Europe, but modern civil service systems were often directly inspired by the Chinese system.

Mencius — Mencius

The self-titled work of the second greatest Confucian thinker, Mencius — also known as Mengzi — was the Plato to Confucius’ Socrates. Born roughly a century after Confucius’ death, Mengzi was raised by his widowed mother. Her efforts to provide him with the environment needed to be a great scholar made her noteworthy among women in ancient China.

In his book, commonly called Mencius, he expands on the ideas of Confucius and introduces new concepts that became influential in their own right. Unlike the short, choppy nature of the Analects, Mencius’ work often takes the form of dialogues in which ideas are debated and explained.

He introduced the idea that human nature is good to Confucian thought. However, he maintained that we are all born with these “sprouts” of virtue that must be cultivated through a proper environment and education to be fully actualized. These sprouts correspond to what we might call the cardinal virtues of his system: benevolence (rén), righteousness (yì), wisdom (zhì), and propriety (lĭ). For example, while all people have an innate sense of compassion, only through proper education, reflection, and a proper environment will a person develop the virtue of benevolence. In this way, education is used to express innate traits. As he puts it:

“He who exerts his mind to the utmost knows his nature.”

In this, we can see an interesting overlap between the Confucian ideal of self-development through education and the Taoist notion of returning to the original self. Mengzi also argued it was important to take a critical stance on every text, going so far as to argue:

“It would be better not to have the books than to believe everything in them.”

While Confucius could not impact policy after leaving office and taking up philosophy, Mencius is thought to have had some influence. Mencius’ views on Confucius would become something akin to the gospel.

When Neo-Confucianism developed in the Song Dynasty, his ideas would be codified and placed alongside the works of Confucius as classics. However, Western translators initially dismissed his works in favor of the original works of Confucius, limiting his impact elsewhere. Today, with the revival of Confucian thought, his ideas on virtue ethics are being reconsidered, especially as an alternative to Aristotle. His ideas on moral development are also being reconsidered.