Fear of scams drives your behavior in nefarious ways

- Fear of being played for a fool is an underappreciated driver of human behavior.

- To prevent being labeled a sucker, people often make decisions that go against their best interests and core values.

- One way to lessen this influence on your decision-making is to be explicit about your goals and intentions in social interactions.

At the turn of the 20th century, George C. Parker sold the Brooklyn Bridge for a few hundred dollars. It would be the most boneheaded deal in the history of deals if not for the fact that Parker did not own the East River-straddling monument. He did, however, have many forged deeds that he would sell to anyone foolish enough to buy. By some accounts, the police had to escort Parker’s victims from the bridge when they tried to erect toll barriers.

Parker was hardly alone. William McCloundy, Reed C. Waddle, and Charles and Fred Gondorf claimed to have run the Brooklyn Bridge scam. Now, there is some question as to whether these stories are true or popular folklore spurred by self-made myths of retired criminals. (They were, after all, con artists.)

Nonetheless, history is full of similar warnings to would-be suckers. From Ponzi schemes to welfare queens, actual conspiracies to imagined criminal cabals, the lesson is clear: Always be on the lookout for the next scam, or you’ll be the sucker.

But is it possible that we’ve learned the wrong lesson? Has our hyper-vigilance for the next con distorted our decision-making and thinking over social issues? I spoke* with Tess Wilkinson-Ryan, law professor and the author of the new book Fool Proof, to discuss these questions as well as how we might contend with such fears in a world seemingly filled with exploitation.

Kevin: In your new book, you posit that fear of playing the fool, sucker, mark, rube, nitwit, jabroni, or nincompoop is not only a universal psychological phenomenon — as perhaps evidenced by the many names we’ve devised for it — but that it’s also an underappreciated driver of human behavior.

What led you to explore that question?

Wilkinson-Ryan: I was in graduate school, and I had finished my law degree and was studying how people reason through moral problems. I was especially interested in places where their moral intuitions were in tension with the legal rule. So, I started asking people about contract cases, and I got a lot of great insights.

But I also got information that struck me as intense. Some responses to these fictional breach-of-contract situations were along the lines of, “I can’t believe what’s happening to America today.” Imagine you got your floors refinished but the work wasn’t done on time, and people responded with, “That’s what I’m saying. Everything is terrible!”

That was the tenor, and it felt to me that they were responding to something that wasn’t overtly in the situation I was posing. I thought that what they were responding to was the idea that when someone breaches a contract, they make a sucker of the other person.

At the same time, I researched various economics games and read an article that influenced me quite a bit titled “Feeling Duped.” And I thought that, in a lot of these cases, what’s actually happening isn’t that people are trying to be selfish. They’re just trying to make sure they don’t end up looking like a fool. That seemed like an under-explored explanation for a range of behaviors showing up in these economics games and in my own research.

The fear of playing the fool

Kevin: Let’s continue laying the groundwork. What is “sugrophobia”?

Wilkinson-Ryan: The term was coined in “Feeling Duped,” and it translates to something like “fear of sucking.” [Laughs.] The idea is essentially the fear of playing the fool.

What was so clever was how the authors [Kathleen Vohs, Roy Baumeister, and Jason Chin] invoked the idea of a phobia. I think that’s a helpful framing because we’re familiar with phobias in other contexts as being something that triggers an outsized response. You perceive an amorphous threat out there, and all of a sudden your heart starts racing.

In fact, I’m afraid of snakes. I’m genuinely phobic when it comes to them.

Kevin: As in, can’t be in the same room with one in a terrarium?

Wilkinson-Ryan: Absolutely not! I’m in California right now, and we just went on a low-key family hike, and I just kept my eyes straight on the trail in case there was a California snake out there. [Laughs.]

Sugrophobia captures that same vigilance for the sucker enterprise, and the main argument I’m making is that we are often overreacting.

Most times, when you see a snake, the snake is just going to keep on and not bother you. Similarly, oftentimes you see something that could be a threat, some kind of scam, something you could frame as exploitative, but actually, it won’t cause any kind of loss that you’ll ultimately care about.

And so, the overreaction isn’t that helpful for your ultimate goal — whether that’s making a productive workplace, investing your money, contributing to a charitable cause, or whatever.

Kevin: So, I’m not afraid of snakes, but I would be wary if I saw one on a trail. I’d want to observe it from a distance, assess what kind of snake it is, and pass by safely. I’d like to believe I have a similar approach when it comes to cons and fraudsters. I pay attention, keep my distance, and don’t do anything foolish.

But in the book, you discuss how our fears and aversions to being fooled can distort our perceptions and constrain our moral imaginations without us realizing it. Could you explain how they do that?

Wilkinson-Ryan: Sure. I’m coming to most of my work from a social science perspective. Particularly, I’m in the subfield of psychology that — when we’re not calling it “behavioral economics” — we call judgment and decision-making. And there’s a lot of literature on the idea of heuristics and biases.

Heuristics and biases are basically shortcuts in judgment and decision-making, and we take a ton of shortcuts because it’s the sensible thing to do. You have to navigate this world, and you can’t be bringing the maximum cognitive effort to every single decision. Otherwise, you would literally never get out of your room in the morning.

The interesting thing about heuristics is that they are basically over-extensions of sensible shortcuts. You’re following a sensible rule, but you’re following it to the wrong place. I describe this as being the same type of phenomenon.

In all kinds of cases, it’s totally sensible that you don’t want to be exploited, right? Exploitation is, for sure, a bad thing. I’m not suggesting that it’s something we want to be embracing. If you want to invest for retirement, obviously the better choice is to put it in a well-known retirement fund than a friend who has a great new idea for a business. Because I’m less likely to lose the money I need to retire. Another way in which exploitation matters is it creates dramatic inequalities in society.

The concern I’m raising is that this sensibility — which usually directs us toward things that matter — may reorient us toward actions that don’t reflect our core values and goals.

I use interactions with university students as examples in my book. Not because it comes up in my day-to-day so much, but because there is a real discourse around how to think about students and problems like cheating — especially now with ChatGPT, right?

“Sugrophobia captures that same vigilance for the sucker enterprise, and the main argument I’m making is that we are often overreacting.”

– Tess Wilkinson-Ryan

Kevin: And before that, there was the Chegg cheating scandal.

Wilkinson-Ryan: That’s right. Imagine that a student asks for an extension for a family emergency, and for some reason, their story raises your hackles. You think, “This doesn’t seem quite right.”

It’s easy to start planning how to protect yourself against potential exploitation in this situation without doing a gut check. You need to consider, “What exactly am I worried about here? What exactly are my goals?”

Sure, it’s not totally clear that the extension is for a bona fide reason, but I would be horrified if I was treating a student with suspicion in a situation where they had a genuine problem. That mistake, to me, would be a much bigger deal than the mistake of letting something slide.

Kevin: That makes sense. If a student ends up cheating you, you’re going to feel exploited and lose some time fretting over being taken advantage of. But in the reverse case, you’ll lose a lot more time worrying that you didn’t help someone when they needed your support.

Wilkinson-Ryan: Exactly. If you asked me which of my core values is at stake, they would be compassion, empathy, and some sort of graciousness — modeling what it looks like to be a professional in a humane way. That matters a ton to me.

A kick down the social ladder?

Kevin: And it’s not just fear of losing money or time. As you point out in the book, these fears are closely tied to things like status and reputation. Why is that?

Wilkinson-Ryan: People feel that being taken advantage of is being demeaned or brought down a peg. Do you know the expression “to put one over on someone”?

Kevin: Mm-hmm.

Wilkinson-Ryan: I think it’s more literal than you would think. The sucker is canonically low status. Intuitively, the dynamic of someone taking advantage feels like they are putting you beneath them in some implicit sense.

I should say that I don’t spend a lot of time in my day-to-day life thinking about status, and I don’t think a lot of people do either. Not explicitly. As in: “Listen up, guys, what I’m really trying to do here is make sure you all see how high status I am.” That would be an incredibly embarrassing goal. It feels so shallow.

Kevin: Right.

Wilkinson-Ryan: But humans are super sensitive to status. Even if we’re not talking about it, we’re often thinking about it. Your social radar for status has been well-honed over time. Your ability to go to a party and make out the status of people in the room is way better than you’d want to admit. I’m sorry. Not you personally.

Kevin: [Laughs.] No, I get it. My son started middle school this year, and I can see that radar developing.

Wilkinson-Ryan: Yes. My daughter is in middle school, and my son is in high school, and they have a hyper-local antenna for what things mean in ways that are utterly unclear to the adults. My husband and I will ask, “Why don’t you be friends with those kids? And they’re like, “Oh my god! Can’t you tell those are literally the most popular kids in school? I can’t just go over there and chat! That’s not how it works.” [Laughs.]

So, the sucker stuff is attached to status. It’s a threat to status because being taken advantage of means you aren’t, for example, savvy.

I’m making an empirical claim there, and I lay out evidence for it in the book. For example, there’s a bit of research from studies in criminal law that suggests that people feel this way about victims of certain crimes. They feel they have been taken down a peg essentially by their victimization.

But I’m resting on my intuitions, too. Part of my argument is that it flows logically that if what a scam does is threaten to kick the sucker down the social hierarchy, below the operator or con artist, then the worst scams are the ones that come from people who you view as already lower than you. It means you’re falling further down the social ladder.

Kevin: I think everyone has been on the receiving end of a scam or two in their lives. I’ve never been swept up in, say, a pyramid scheme before, but I think of several times I’ve been taken advantage of.

Wilkinson-Ryan: It’s unavoidable. It’s not something you can avoid a hundred percent of the time.

Kevin: Even so, when I find out that my dad has fallen for something, I’m like, “Come on, dad, what were you thinking?” I certainly have less empathy than I should.

Why do you think we act that way when we find out someone else has been scammed given that we’ve all played the sucker at some point?

Wilkinson-Ryan: That’s a good question, and I don’t think I’ve even answered it in the book in a satisfying way. One thing is that most people think they have a good BS detector — in part for the straightforward reason that we think that we’re better at all kinds of things than others.

Over-optimism is a well-documented phenomenon. For example, there’s a statistic that — something like — 93% of American drivers believe they’re better than the average driver. Obviously, the math does not bear that out. And I think that this is a bit the same.

Unless we’re always being taken advantage of, it becomes a narrative we have about ourselves. We don’t quite realize the extent to which being scammed is in some ways unavoidable.

About your parents getting scammed — and both myself and my husband have this exact same worry — I think that’s because, in part, our parents might be targeted in ways that are different than we would be targeted. Their body of knowledge is a little bit different. If you started on email when you were 10 versus when you were 55, that changes things.

So, I think it really has to do with the self-serving stories we’re telling ourselves because it feels terrible to think that you’re just wandering around totally vulnerable in some way.

Revenge is sweet (and costly)

Kevin: But sometimes, you just know you got scammed.

In the book, you point to research showing that we’re not only driven to make scammers pay. We’re so driven that we’ll do it even if we incur greater losses ourselves. Can you speak about that?

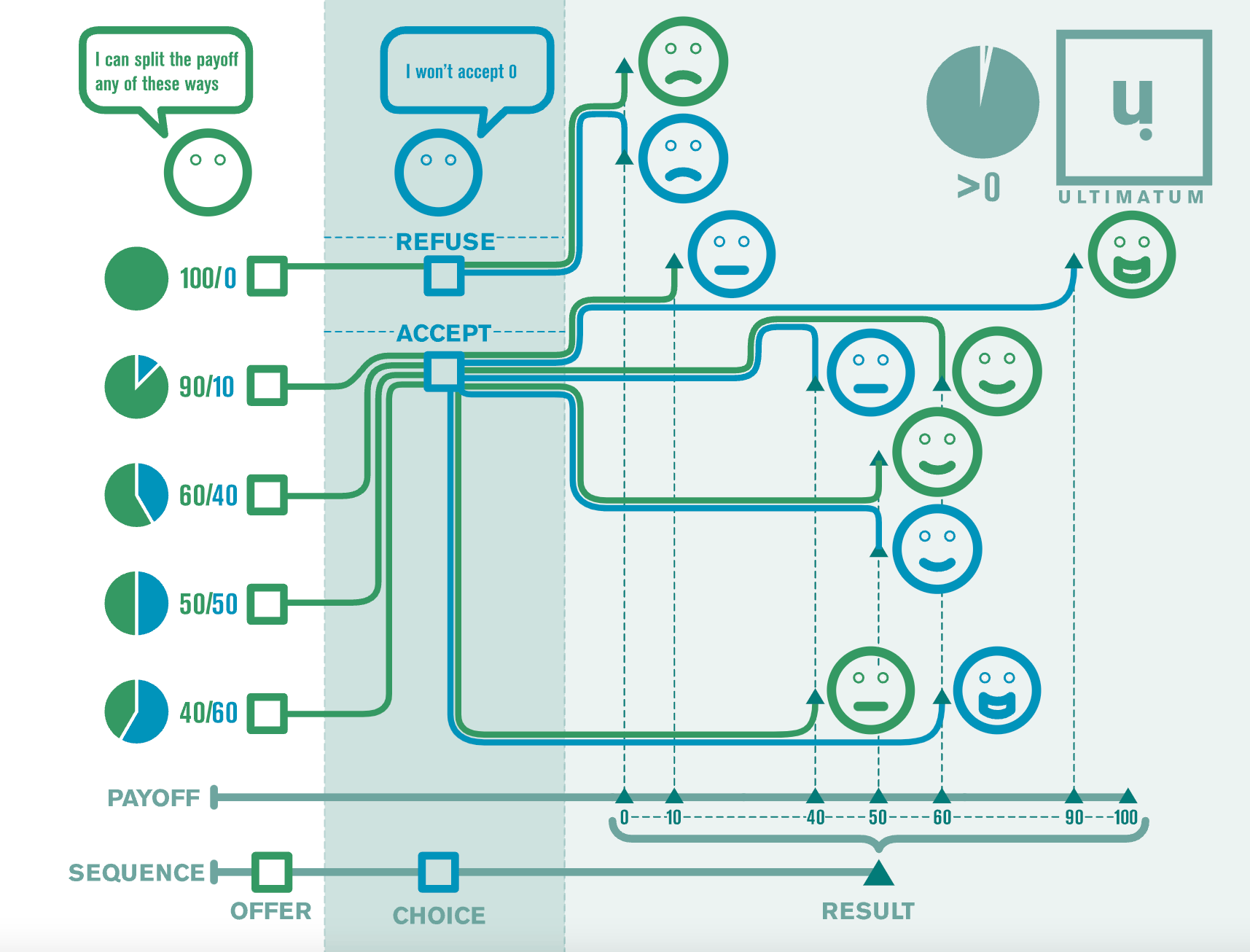

Wilkinson-Ryan: Some of the research that got me thinking about these questions is a set of studies around what’s called the ultimatum game. The rules are very straightforward.

There are two players: One player, the proposer, is given $10; the other player, the responder, isn’t. The proposer then says, “How about if we split the money this way?” You know: “I keep $6, and you get $4” or “I keep $5, and you get $5” or “I keep $9, and you get $1.” And the responder can say yes or no.

If the responder says yes, they take the money in line with the proposed allocation, and everybody goes home. If the responder says no, nobody gets anything. That’s the whole game.

Kevin: Okay.

Wilkinson-Ryan: I think this game is clever because the responder is stuck with two choices: They can go along or ruin it for everybody. And every time a responder says to ruin it, he or she is literally refusing to take money to make sure that they’re not the one getting the short end of the stick.

As an aside, I tried to explain this game to my daughter — she was 9 or 10 at the time — and she said she would accept even if it was a 10-0 split. I was like, “Really?” And she said, “Yeah, let them have their money. What do I care?” It was such a funny moment. I felt a surge of pride and then also a bit of concern. [Laughs.] It’s an interesting intuition.

But in the lab, as you would imagine, the acceptance rates really start to drop off at roughly the 7-3 and 8-2 splits. Barely any of the responders are saying yes then.

One of my favorite versions of this experiment let some of the responders send back notes, and the notes really spoke to the question you asked earlier about status. They were like, “What? You think you’re better than me?” or “See what’s going to happen? You’re going to get nothing!”

Kevin: Did any of these games have someone on the inside working for the researchers?

Wilkinson-Ryan: You mean like a confederate?

Kevin: Yeah.

Wilkinson-Ryan: In most economics games, there are really strict rules about deception.

Kevin: Gotcha.

Wilkinson-Ryan: Which makes them incredibly expensive to run because you have to wait. If you’re trying to discover how people respond to low offers, you have to run through a lot of people that divide the cash evenly. Everyone goes home happy, and you’re like, “Well, great.”

Kevin: [Laughs.] It’s nice to hear that most proposers go with 50-50 splits, though.

Wilkinson-Ryan: I think most people track the intuition. They understand that if they offer a smaller number the other person is probably going to say no. You can also just imagine that the task is kind of funny. Take $10 and divide it between two people. Seems like the normal thing would be $5 and $5, right?

Kevin: It all goes back to grade-school math. So, how do these behaviors begin to scale up once we start looking at them at the societal level?

Wilkinson-Ryan: When I first started researching this project in earnest, I was thinking about it on an individual level. But as I was going, I started to take notice of what I thought were ways that tropes of suckers inflected a broader narrative about winners and losers in society. I revisited a set of articles that I had read about sex and gender stereotyping.

So, one way you can think about prejudice is as animus. That’s for sure a thing, but stereotypes also have content to them. There are particular ways in which different groups are accused of or believed to share common traits.

One of the things that caught my attention was the ways that suckers and schemers kept popping up in different narratives about what we would otherwise think of as being traditional social hierarchies in the United States [patriarchy, racial hierarchy, etc.].

One of the ways that the sucker construct is operationalized in society is by giving some groups in the social order very little space between being a sucker and being a conniver. As such, they are either they’re going to be stereotyped as fools — for example, the historical view of women as being childlike and naive — or, if they start to insist that the deal they’ve been offered isn’t acceptable, then they get pigeon-holed as being a scammer. Others claim their desire for equal rights is actually an attempt to milk the system, dominate other groups, or something like that.

In the book, I talk about it as a tightrope. One way of keeping people in their place is by insisting that they walk a very narrow path between being accused of being either a fool or of taking advantage.

“One of the ways that the sucker construct is operationalized in society is by giving some groups in the social order very little space between being a sucker and being a conniver.”

The upper-crust con

Kevin: Connecting that with our discussion of status and reputation, you mentioned that people worry a lot about being taken advantage of by those lower in the social hierarchy.

But can’t schemes come from the above you in the social hierarchy, too? I’m thinking here of upper-crust fraudsters like Elizabeth Holmes, Sam Bankman-Fried, and, of course, Bernie Madoff.

Wilkinson-Ryan: For sure. There’s no question that Madoff was running a Ponzi scheme. That was a person with more wealth and social status than most of us running a scam. We should call it what it is.

And there is a robust discourse about exploitation. Think about political disagreement. On the left, there’s the view of exploitation by Fox News, right? On the right, there’s a view of exploitation from mainstream media. Those are serious conversations about exploitation and exploitative relationships.

Where I think there’s a bias is that there’s more slack for exploitative behavior from above than below. It’s easier to call out scams from individuals than from, say, large wealthy institutions. It’s also wrapped up in a kind of compliment sometimes, right? This person is a really savvy business person. You’re less likely to give that kind of credit when part of the narrative is about reinforcing a traditional hierarchy.

Kevin: Okay.

Wilkinson-Ryan: There’s the content of sexist stereotypes. Like, a woman is trying to convince a man of her interest in him because she wants his money, right? People think she is some sort of “gold digger” — an expression I would not normally use, but that gets to the idea that this kind of scheming or line-jumping as being particularly problematic.

It’s not that we don’t perceive exploitation everywhere. It’s that, in some cases, people can reach for easier answers and feel better not thinking the whole system’s a scam. Is this a scam or just business as usual? Is this a scam or just capitalism?

Whereas if someone is in a weaker bargaining position compared to me, and I think that they might be trying to take advantage, that’s something I can act on. I can do something about that.

Kevin: I see. So, even if someone recognized Madoff’s Ponzi scheme for what it was, most people couldn’t do anything about it. He’s too high up on the social ladder. But when someone is lower on the social ladder, then people feel as though they can do something about it?

Wilkinson-Ryan: You can think about it in terms of the regular world. How often do people lose their tempers with employees who are, essentially, just low-paid agents of a larger business? People screaming at airport assistants or giving a cashier a hard time. And for what?

Those are cases where you might be able to bring your emotional energy and social capital to bear and get some kind of relief.

The cool out

Kevin: Can you explain what the “cool-out” is, and how it plays into what we’ve discussed so far?

Wilkinson-Ryan: I originally wanted to title the book Cooling Out the Mark, but that was obviously a terrible idea because not everybody is a hardcore Erving Goffman fan. [Laughs.]

So, Goffman is a founding figure in social psychology, even though he was a sociologist, and he wrote a lot about the way people live their lives as though they’re on a stage and they’re trying not to mess up. His thing is basically that what’s driving a ton of behavior is people’s incredible resistance to being embarrassed.

He has this whole riff where he says to imagine you’re a gangster. It’s not super relatable, okay, but you’re a gangster, and you’re running an extortion scheme. The victim finally realizes they’ve been scammed and is now furious. What do you do? Well, in the crime world, one person’s role is to play the cooler. The cooler’s job is to persuade the victim not to lose it, not to go public, and not to call the police.

Goffman says there are all kinds of things in your regular life that act like a cool out. One example might be someone who has been overlooked at work and starts to get mad. And so, the company gives them a consolation prize, like a fancier title. You’re going to be the vice president of nothing and nothing. It’s conciliatory; it’s a cool out.

Those cool-outs are external, but I think a lot of the time, the cooler is yourself. You don’t want to feel terrible about something that’s happened, and there are things you can do to explain away the situation.

Part of what I’m considering is what motivates self-cooling. In some cases, we’re motivated to feel like we have a good BS detector or are good judges of character. But in others, the right thing to do is to say, “This situation isn’t right. This isn’t right for people. This exploitation, taking my goodwill and causing me and others harm that matters.”

“We don’t quite realize the extent to which being scammed is in some ways unavoidable.”

Kevin: Would you say the self-cool-out is a blessing or a curse in our psychological makeup?

Wilkinson-Ryan: It’s a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing because no one wants to feel bad all of the time. But it’s a curse because it encourages people to not share knowledge with each other or keep quiet about something bad.

Speaking about parents getting scammed, one of the concerns in cases of elder fraud is the failure to report it. In part, that’s because it’s embarrassing. No one wants to admit that they’ve been duped in some way. The problem is that it means the exploitative practice gets to keep going on.

Kevin: I can see that.

Wilkinson-Ryan: And there are cases where you need to cool yourself out on purpose. You need to say to yourself, “What am I doing right now?” You need to step back and really consider what you are trying to do or what you want.

I give an example in the book. My sister was biking a long, long mountain road in Vermont, and she got super thirsty. But she almost refused to buy a Gatorade because she thought the store was charging too much. She’s out in the middle of nowhere and super thirsty. There’s almost nothing that would be more valuable to her at that moment than a Gatorade. So, what are you doing? Pay the six bucks, drink the Gatorade, and move on.

Kevin: [Laughs.] When I read that, I remember thinking that there must be a lot of thirsty bikers along that stretch of road.

Wilkinson-Ryan: It’s just not worth asking yourself, “Is this store charging too much? Is its price in line with some Platonic ideal of Gatorade pricing?” All that matters to you should be what it is worth to have a sports beverage.

Kevin: I’ve definitely done that myself.

Wilkinson-Ryan: Who hasn’t?

Better a wise fool

Kevin: Final question: How can we better manage sugrophobia so it doesn’t have such a strong distorting effect on our decision-making? What are some practices we can use?

Wilkinson-Ryan: First, keep your eye on the actual goal. When you are in a difficult situation — with moral, ethical, or material stakes — try to articulate for yourself what your goal is. What is the outcome that matters most to you, or what are the values that you’re vindicating in this situation?

If you’re buying a used car from the used-car lot, and your only goal is to get a reasonably functional car that’s as inexpensive as possible, then go ahead and have your scam radar turned up to the maximum extent.

But in most situations, that’s not the only goal. In most situations, the goal will have a couple layers to it.

One goal that I try to apply to a lot of areas of my life is integrity. I think that often means showing some grace, some compassion, and letting stuff that doesn’t matter slide. I don’t need to make other people’s lives harder for no reason.

Now, if your explicit goal is to never be the sucker, that’s a whole different value system. [Laughs.] In this case, you would want to have an active radar. But for most people, I think the goal is not to make sure you don’t let anyone get any little thing over on you. The goal is going to be something like integrity or human connection.

And one of the things about accusing people of being schemers is that it really is a way of severing human ties. It’s a way of distancing people from each other. It means that how you were thinking of yourself as being compassionate or living gets turned into something nefarious. I think it’s very alienating.

For most people, I think the goal is not to make sure you don’t let anyone get any little thing over on you. The goal is going to be something like integrity or human connection.

The second sort of touchstone is being explicit about those goals. In the book, I talk about this like accounting, which is a bit silly, but the idea is that people often don’t think about their fears in a deep way. Instead, they just warn you away from a whole set of choices.

In the case of being suckered, of course, that’s a real threat in all kinds of situations. It’s a real possibility that if you loan someone money, you’re not going to get it back. I think it’s totally sensible to factor that into your decision-making. But be as explicit as possible about it and functionally weigh it against any other goals.

Let’s say my sister asks me to borrow money for a car payment. Now, my real sister’s car is so much nicer than mine, so this is an incredible scenario for me to even be thinking about, but let’s go with it. [Laughs.]

One of the things I’m thinking about is whether or not I will get repaid. Right? Is this a situation where I lend this money, and I never see it again? That’s one thing that matters to me. But it also matters to me whether my sister is happy and whether she can afford her car payment.

Yes, I’m going out on a limb. I may not get my money back, but that’s also not my most important goal. And the more I can be explicit about my goals, the more I can act according to my values. The less contaminated my decision matrix will be in ways that distort it.

Kevin: Where can our readers find you online to learn more?

Wilkinson-Ryan: My website is tesswilkinsonryan.com. The book is available on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and independent booksellers. It has an audiobook version, too. And if anyone wants to, they are welcome to look up my Penn Law homepage and get a lot of practice problems for contracts.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

* This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.