The 8 wonders of life — and how they can transform yours

- Awe occurs when we experience the vast and the mysterious.

- While we tend to conceive of awe on a grand scale, research by psychologist Dacher Keltner suggests we can experience awe in everyday experiences.

- Keltner calls these experiences “the eight wonders of life,” and he explained to Big Think how they can promote a sense of well-being and connection with humanity.

What do you think of when you imagine something awe-inspiring? Is it a chance encounter with the aurora borealis or a rare comet? Is it being there in person when your favorite band gives their last performance? Or maybe accomplishing something that other people told you was impossible?

If your answer was along those lines, guess what: You’re spot on! Those momentous events are awe-inspiring. Life-affirming even. They leave us gobsmacked, raise the hairs on the backs of our necks, and render us incapable of expressing ourselves beyond a Keanu Reeves-worthy, “Whoa!” But as stunning as such moments are, they represent only part of life’s awe equation.

Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at the University of California, has been researching awe for more than two decades. During that time, his research has shown that it’s not just the extraordinary that imbues us with a sense of awe. We can find awe in our daily lives. He calls these everyday inspirations “the eight wonders of life,” and in his new book, Awe, he describes how they play a role in our health, happiness, and well-being.

I spoke* with Keltner to discuss what emotions are, the current research into awe, and how we might bring these eight wonders into our lives.

Kevin: To start, let’s lay the foundation with a big question: What are emotions?

Keltner: Emotions are brief mental states that have a subjective feeling that defines the emotion and animates particular patterns of action. Then the great philosopher Jean-Paul [Sartre] talked about their transformative quality. Emotions shape your thoughts and how you see the world. So, if you’re feeling lust and desire, you’ll see everything through the lens of desire, right?

In most schools of thought, those two dimensions of emotions — motivating action and guiding cognition — help individuals navigate their social lives. If I see somebody suffering, compassion leads me to tend to their needs. I express gratitude to others with a nice embrace, showing that I care about the cooperative nature of our relationship. I get angry at inequality and protest in an attempt to restore justice.

So, emotions are these brief states that help us keep the structure of our social lives relatively stable and beneficial to our interests.

Kevin: That element of social connection. Is it the reason we express our emotions so readily in our faces and body language?

Keltner: There’s a huge literature that I’ve been a part of on non-human signaling. Macaques will vocalize fear to signal that there’s a snake or a hawk in the vicinity. Humans have a rich vocabulary of 15 to 20 emotional expressions in the face. These have information that gets others to act in a fashion with how you’re responding to a situation. One of my favorite examples of this is in babies. Babies come into the world and use caregivers’ emotional vocalizations and expressions to find out what’s good and dangerous things to avoid.

Kevin: When my son was younger, I would tell him not to touch a hot stove. But it was less me saying, “Hot!” because he didn’t have a concept of hot yet. It was more my tone and facial expression that triggered his response to steer clear?

Keltner: There are classic studies by my colleague Joe Campos. He positioned infants on the edge of a visual cliff. For the infant, it looks like he or she might fall; however, there’s a solid plexiglass surface over it. If the parent positioned across the way looks scared, the baby won’t go across. If the parent is smiling, the infant is like a lemming. They go right over.

So, we use facial expressions and vocalization to convey emotions to other people and to signal what’s important in the world. Who can you trust? Is this food rotting? Is that street dangerous? It’s an old, powerful language.

Kevin: And it seems we never quite outgrow that. There are those experiments where they fill a room full of smoke, but because nobody else is bolting for the door, the participants just kind of look around and stay seated.

Keltner: [Laughs.] Exactly. And all you need to do in those experiments is have one person shout, “Oh my god!” Then everybody takes action. It all helps us disambiguate the complex situations that are part of our lives.

An emotion of a different color?

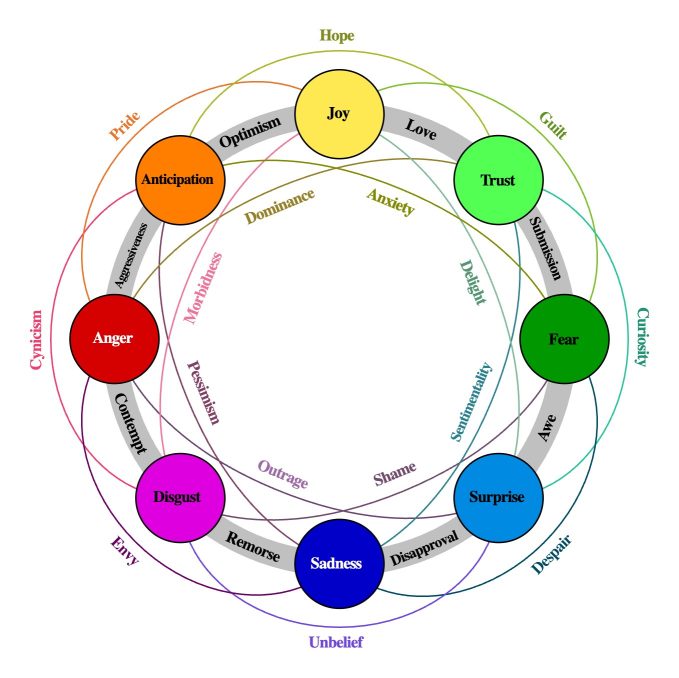

Kevin: One question I’ve always had regards those wheels of emotions you see online. They look like a color wheel. Are emotions like that?

As in, you have your primary emotions, like happiness and sadness, and then secondary and tertiary emotions that combine those primaries into various shades? Or are we talking about distinct things with each emotion?

Keltner: Thank you for asking this question. Those color wheels are kind of made from intuition. Nostalgia is a mixture of sadness and love. And that may be true, but the subject is deeper, and here’s why.

There’s a whole school of thought in philosophy, and it really begins with neuroscientists like Jaak Panksepp and philosophers like Mark Solms who say that the core of consciousness is feeling that a central realm of our conscious mental life is how we feel about the world. Do we feel angry or jealous or proud or ashamed or amused, right? I agree with that, and I think a lot of people feel that emotions are basic ways of perceiving reality in the moment.

As William James said, we’re always shifting from one lens to another in the stream of conscious mental life.

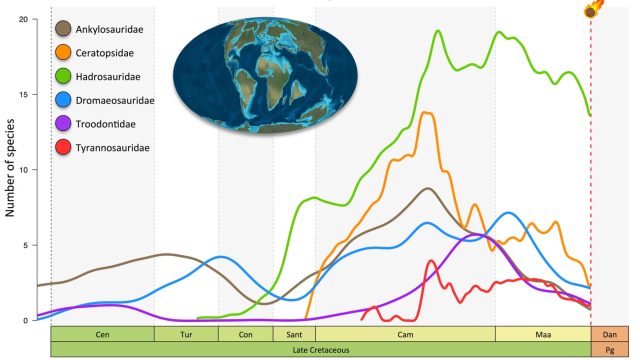

That leads to your question: What are the emotions that are these basic states? For a long time, the field [followed] Paul Ekman’s famous work on facial expressions and basic emotions. He felt that there were six: anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, and happiness. Panksepp felt you could trace most of those basic emotions back into the mammalian brain, but that was conjecture. They just sort of thought about it and said, here are the six emotions.

For the past six years, I’ve worked with computational cognitive scientist Alan Cowen. He and I did a series of papers where instead of assuming those emotions are basic, we performed what we call a bottom-up approach. We let people respond emotionally to thousands of short film clips or pieces of music or facial expressions or paintings, and they rate them on a bunch of emotions. And then we did a lot of fancy statistics.

Alan found two important points here. Number one: There are about 20 states that seem to be the basic states of consciousness. There are the core negative states: fear, disgust, guilt, horror, anxiety, and so on. And then there’s a whole rich array of basic positive states: love, desire, amusement, compassion, gratitude, [etc.]

The second thing is there’s this widespread idea in what’s called constructivism — that the basic modes of reality are just good and bad, high and low arousal. Oh, I’m aroused and this is a good thing, and then I add all these culturally specific interpretations upon this good aroused state to call it an emotion. We find that’s not true. What’s primary is not the goodness or badness of things. It’s these emotions.

I would encourage people to go to alancowen.com and read the papers and see his maps of emotion. They’re amazing. It shows us that the core of our mental life is these 20 emotions, and then you can mix them up. Like, nostalgia might be a little bit of sadness mixed with love. When those combine in somebody my age is mine, I’m suddenly, God, I feel nostalgia for my children when they were young like your child.

Kevin: To round out our discussion of emotions, to what degree are emotions culturally constructed or not?

Keltner: There are radical constructivists who say there’s almost nothing shared across humans. It’s all constructed according to our cultural backgrounds through norms, ideas, concepts, scripts, stereotypes, and the like. I think that the [cultural] thumb is on the scale, but it’s much smaller than you might imagine.

We’ve done the largest scale studies of aesthetic experience in response to music, and we find that about 50–75% of an emotion is universal. That is, how we respond emotionally to a piece of music is shared across humanity. We know when music is sad or terrifying or energetic. So, there’s a lot that’s universal.

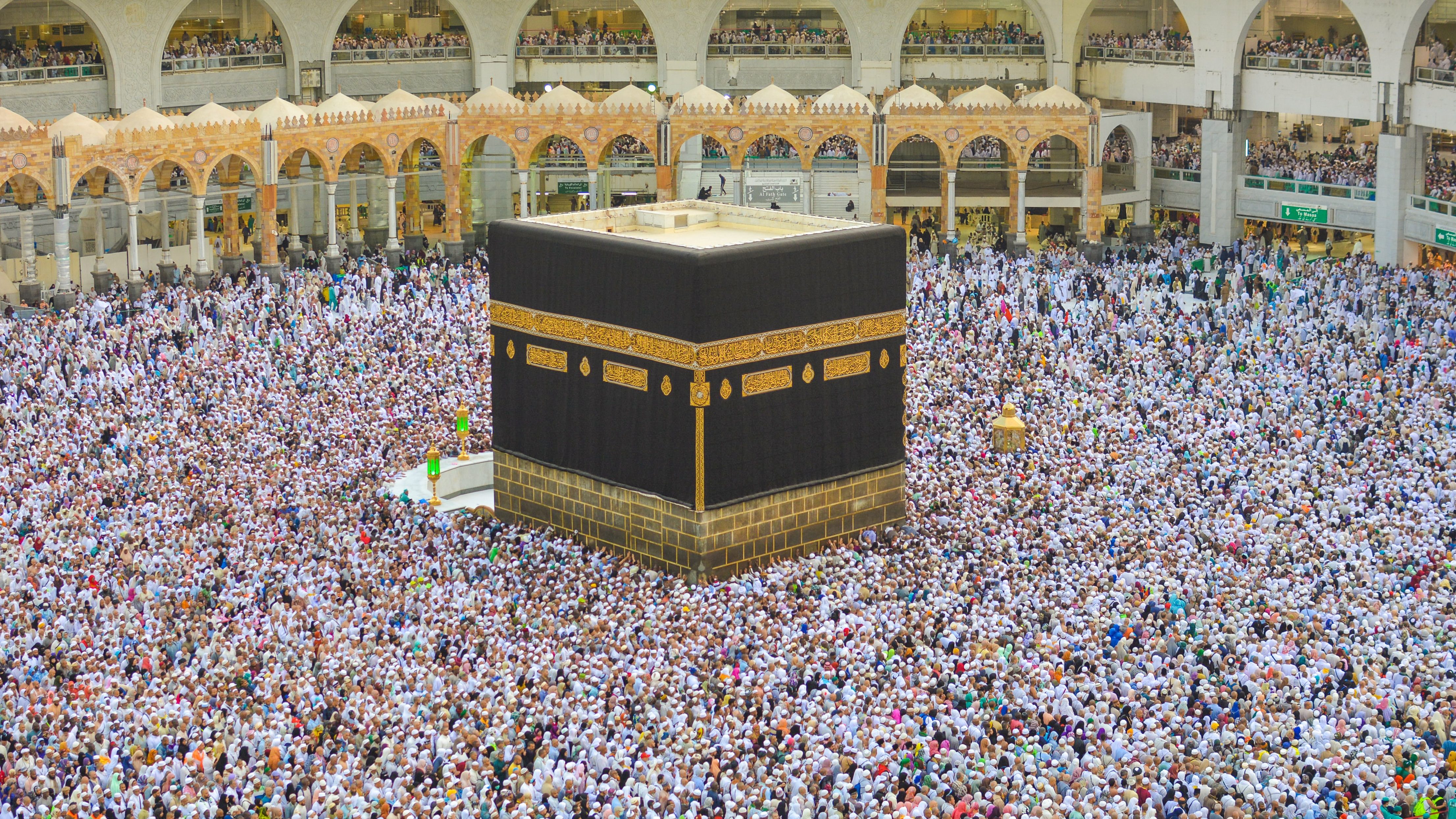

But then the cultural variations can be profound. For example, in our research on awe, we found that in U.S. and Western European cultures, awe is about nature. In China, it’s very social. It’s about my teachers and that master mathematician or that violinist. You go to the Middle East, and it’s religious. In secular Holland, awe has nothing to do with religion.

So, it’s always both. Variations are fascinating and important in a lot of countries, but there’s a lot of universality, too.

The awesome power of awe

Kevin: It’s interesting that you mentioned the Middle East. In your book, you mention that events like the pilgrimage to Mecca are awe-inspiring for many — collective effervescence, you call it. Until reading that, I wouldn’t have associated such a pilgrimage with awe. Religious duty maybe. Social requirement, but not awe. As you said, my go-to idea of awe is more like hiking the Cascades and the vastness of space.

That leads us to the question: What is awe?

Keltner: Awe is an emotion, a brief experience we have in response to vast and mysterious things we don’t understand. And as I’ve studied it over the years, I’ve come to believe — like Jane Goodall and Albert Einstein — that awe is in many ways our most human emotion. We encounter these vast mysteries: What is life? How do I make sense of the solar system? Why are mountains so large? How can you make music? And the mind has this emotion that kicks things like wonder, curiosity, and exploration into gear.

Kevin: Could you give our readers an example of how you can study the vast and mysterious in something antithetical to both as a lab?

Keltner: Man, it took a long time to figure out how to study awe for the reasons you’re hinting at. Labs are like vacuums of humanity. So, the first thing we did, Kevin, is we got out of the lab.

Kevin: [Laughs.]

Keltner: We studied awe with people looking in the trees or at big views. One student went to the eclipse in Oregon. Others went to music events or concerts or sporting events. Or prayer and meditation, right? This is an emotion where you’re going to have to be strategic and opportunistic about it.

Second, we relied on the kinds of culture that we’ve been developing for thousands of years to produce awe. We showed people BBC documentaries on nature, and it just hits them with awe. We had people listen to awe-inspiring music. We did work with Google Arts and Culture and immersed them in the great paintings of the world.

And the third way that we studied awe — and it is so fascinating; I didn’t expect this — is to have people remember experiences of awe and tell stories about them. Kevin, tell me the last time you felt awe in nature or at a music event.

I’ve come to believe — like Jane Goodall and Albert Einstein — that it is in many ways our most human emotion.

– Dacher Keltner

Kevin: Hm. Every winter, a flock of Barrow’s goldeneyes flies in and nests in the bay by my home. It’s inspiring to me that they make the journey every year, and I get to observe them. To borrow a term from your book, I feel like part of a larger system.

Keltner: There you go, right? I suspect that if I had you recall and write about that for five minutes, you’d suddenly be the marvel of it.

Then how we measure awe is we have this wonder self-report. How much awe and wonder do you feel? You can measure goosebumps and tears, which are signs of awe. We can measure people’s bodies and their vocalizations around the world. When people feel awe, they’re like, “Whoa!”

So, ironically, having studied all these emotions over the years — anger and fear, shame and love — awe turns out to be one of the easier ones to measure.

Kevin: What does your research show are the benefits of awe?

Keltner: I wrote the book during a hard time in my life. I lost my brother, and then it was the pandemic. I was feeling disrupted by my loss, and like a lot of people at that time, I was looking for something to get my feet on the ground.

And my students in the lab would come to me with these findings. Awe reduces inflammation in your immune system. I’d be like, “Wow!” Awe elevates activation in the vagus nerve, which is the bundle of nerves that coordinates respiration in your heart rate. That’s good news for your heart. Wow! Awe reduces stress for older people. They feel less physical pain. Wow! We’ve got work showing that awe reduces depression and anxiety. It makes you feel more connected and less lonely. Even when you listen to a piece of music by yourself, you feel less lonely, right? Wow!

So, I think that’s part of why there’s been such a reaction to the book right now. Awe is so good for us. These are just some of the reasons that we should be thinking about finding a bit of awe every day.

Kevin: As a personal aside: I’m reaching that age now where the people in my life are going to start leaving. Opening your book with the death of your brother and your journey of how that loss affected you and helped you grow, it was powerful. I appreciate your willingness to be open like that.

Keltner: Thank you. I had no choice, you know? I was really lost. But it’s fascinating: I’m getting so many emails daily about this part of the book. Things like, I just lost my brother. I lost my child. I lost my mom. It opens the mind to wonder and awe. What is this life we are given about? What happens when people die? How are those people still with us? Those are perennial questions. They’re essential, and awe is a great catalyst for growth — as I discovered thankfully.

Awe across cultures and time

Kevin: To build on our conversation of culture and emotions, you mentioned how awe can be different in, say, China, where you found they are more in awe of teachers than in the West (which was so very, very sad for me).

Keltner: [Laughs.] Yeah. I hear you.

Kevin: I’m curious if our understanding of awe has changed. In the book, you mention that your mother was a teacher of Romanticism, and when I think of awe in Romantic literature and art, it’s far more dreadful and fearful. It also seems to be a more solitary emotion, while your research found it to be very socially-minded as well.

What are your thoughts here?

Keltner: What I hint at in the book is that awe started in human history really broad and then got narrow with the emergence of big religions around 2,500 years ago, and then it broadens out again.

I talk with scholars who know a lot about transcendent experiences in different indigenous cultures, and it’s a more pervasive experience. It’s more part of daily life. It’s associated with dance, ritual, telling stories, and social life. Then we get to the great religions of Western European traditions, and it becomes about God. And I never thought about what you suggested, but a lot of it is fear and dread based on being judged by God. Heaven and hell. Solitary, as in standing alone in relation to God’s judgment.

Then you read Edmund Burke’s book on the sublime and beautiful, which I think is probably the most important book written on awe. It’s the Age of Enlightenment. Industry is arriving. Science is arriving. Maths are expanding. People start to lose religion, and suddenly, Burke is writing a book that’s about secular awe. It’s about light, noise, animals, human beings, sense, and the senses. It’s opening up.

Then the Romantics get to music and nature in the early 19th century. It’s that era that starts to broaden it so that today when I ask people what gives them awe, they say this poem, that sunset, or how much they love sausages. [Laughs.] One guy went mad telling me about the mechanisms of a watch.

Kevin: That’s an interesting connection. I’m thinking of how Keats half-jokingly accused Newton of unweaving the rainbow or how Edgar Allen Poe wrote an essay saying science had put poetry in its crosshairs. Based on your answer, it seems that it’s the combined efforts of science and the arts coming out of the Enlightenment that expanded awe.

Keltner: They’re just different ways of trying to figure out what a rainbow is. The math, physics, and color theory of a rainbow are awe-inspiring. But so is a poetic description of it.

And by the way, the more you learn about awe with tools of rational analysis and science, the richer it gets. For your readers, I’d recommend The Invention of Nature by Andrea Wulf. It is about [Alexander] von Humboldt and this period of Romanticism where there were all these discoveries in science about the sky and ecosystems and the oceans. These weaved together paintings, poetry, and science. Darwin was a great champion of that.

Kevin: Yeah, yeah. You have that phenomenal Darwin quote at the end of the book. [Author’s Note: The quote in question is the final paragraph of The Origin of Species.]

Keltner: Oh my God. Yes. In one paragraph, he offers how nature and something almost like spirit are moving life forward through these processes. It’s beautiful and destructive and always changing. Powerful.

Art and the divinity of everyday life

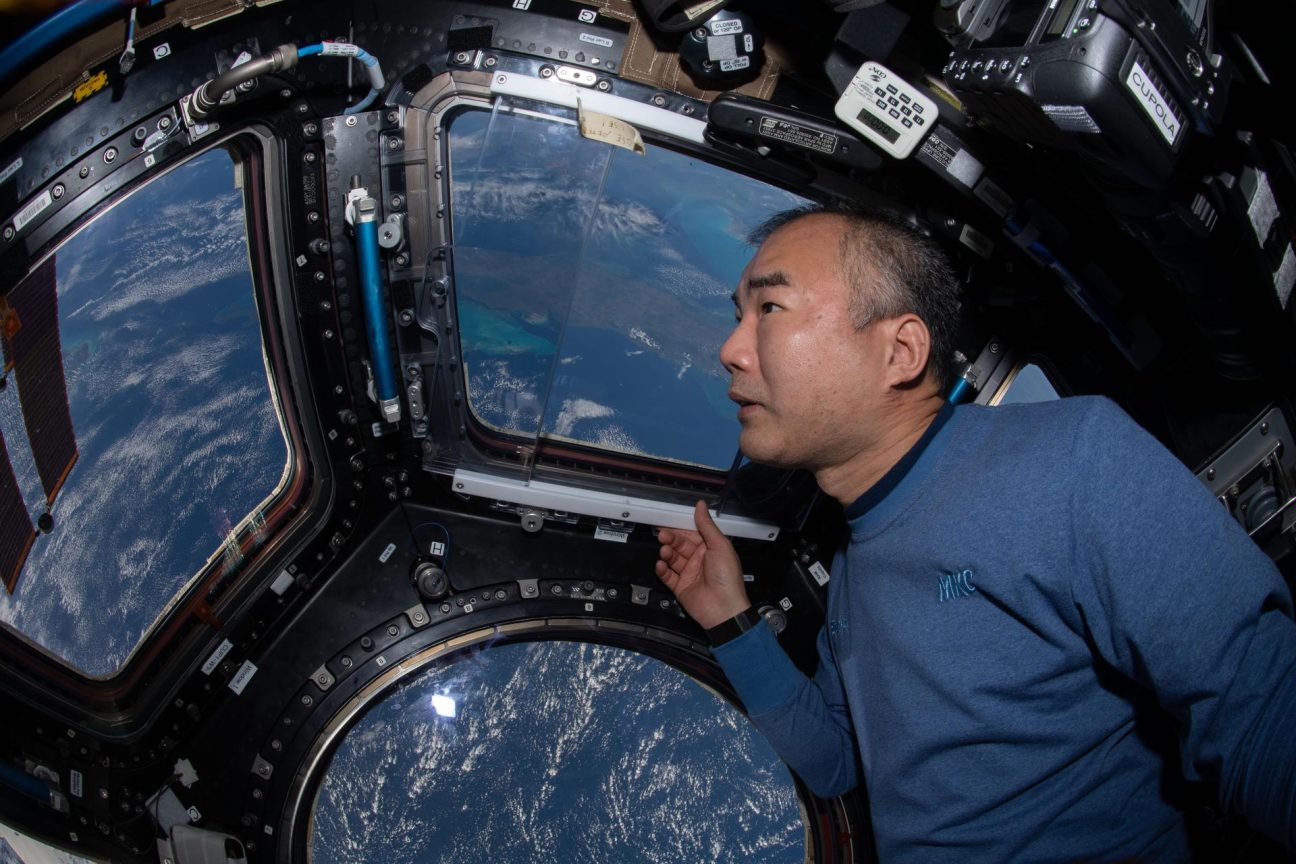

Kevin: We tend to think of awe-inspiring events as large in scale. One that comes to mind is the overview effect, right? Astronauts go to space, seeing the planet. It’s life-altering. I love those stories, but at the same time, I obviously can’t afford to be a space tourist.

Keltner: Yeah.

Kevin: And one of the great things about the book is that it points to everyday sources of awe. What are these sources, and how can we bring those into our lives?

Keltner: When we started to do this research, we’d ask people to write about any awe they experienced that day. We’d read their essays and found that people feel awe two to three times a week, which was surprising. We’re thinking critically, “Is this really awe, or is it just people talking about bubblegum and riding the bus?”

So, we did the research to pinpoint an answer to the questions of where and how? We gathered narratives of awe from 26 countries and found what I call the eight wonders of life in the book. They include moral beauty, nature, and collective effervescence. Then you get to the cultural ones: art, music, and spirituality. You also have epiphany. And our last finding from the study was about life and death. People around the world find it awe-inspiring when life emerges and when it goes.

Kevin: We don’t have time to go into all eight, but I would like to discuss moral beauty. Picking up somebody’s pen when they drop it seems nice but insignificant. But you found that even such a small act of kindness can be a source of awe. How is that?

Keltner: [Laughs.] That’s a difficult question. I can tell you that around the world, these stories poured in about what we call moral beauty. One of my favorites is this guy who wrote about going to a bar his dad ran in Pittsburgh in 1973. He went with his African-American friend, and one of the patrons called his friend the N-word. The guy’s dad — who’s this bartender in this working-class bar — just kicked the racist out. And the guy was awash with awe over this act of courage and kindness.

So the question is: Why would we be moved to tears, get goosebumps, and feel like we have to be a better person when we see these acts of moral beauty?

I think the philosophical part is that when we see these incredible instances, they tell us to activate these ideals in our identities. I’ve done a lot of work in prison, and every time, I go in there and see these guys who have hard lives and come from tough backgrounds. I see how respective they can be, how creative and kind. And I’m like, “Wow! We can have these strengths anywhere.” It inspires me.

What do you think? [Laughs.]

Kevin: I think another part — and I’m going to borrow from your book here — is that it creates a sense of connection with others that limits feelings of isolation and loneliness.

Keltner: I agree. It’s so important just to meditate on that point. No matter where you find awe, you come out with a sense of interconnectedness. That is striking to me. Suddenly, you’re like, “I’m part of humanity. We have good work to do.”

Life can always be divine in some sense, no matter what we’re doing.

– Dacher Keltner

Kevin: In the book, you also talk about music, paintings, and literature. How does art manage this act of bottling up awe for us to enjoy?

When I go to the Seattle Art Museum and see a Matisse, rationally, I know I’m just looking at smears of paint on canvas. But I don’t experience it that way at all.

Keltner: Yeah. In talking to some artists and then looking at the new neuroscience of how we process visual art, I found a few compelling ideas.

One is they directly produce a state of awe in you. They show you how to look at the world. I just recently saw Monet’s water lilies. You look at his water, and you don’t know where the horizon is. You don’t know what’s reflection or real. They’re vast. It’s almost like hallucinating looking at these paintings. A lot of Meso-American art has that quality of direct perception.

A second one is that it astonished us; it leaves us shocked or dumbfounded at the ideas. When I first saw the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibit — I think it was called The Perfect Moment — in the 1980s, it had a lot of imagery of gay sex, graphic imagery that a lot of people hadn’t seen. I was awestruck. It was a whole new world.

Third is the way art is configured and rendered in a painting. It says to think about this idea. I’ve always loved the Dutch masters de Hooch, Vermeer, and Jan Steen. In particular de Hooch, who’s 400 years old. His paintings of Dutch life have this transcendent light that almost feels divine on everyday actions like sweeping the floor or tending to a child. Every time I see them, I’m blown away. Life can always be divine in some sense, no matter what we’re doing.

Get your weekly dose of awe

Kevin: Are there any pre-conditions for experiencing or cultivating awe in our lives?

Keltner: There are eight wonders of life, and they vary in their strength for us given our life histories, our genetics, our cultures, and the like. I would encourage readers, if they want a little bit more awe, to just reflect for a moment. If you’re a music person, take five minutes a day to not do anything and listen to music for awe. Some people are idea people. For me writing this book, one such idea was evolution. I just kept thinking about why we evolved. So, we have receptors for different wonders that matter. Be sensitive to that.

In thinking about the pre-conditions to find awe, I was blown away by an essay by Rachel Carson, “Help Your Child to Wonder.” A lot of parents are thinking about this, too: How do I get my kid to be amazed by the world and not fearful? Curious and not close-minded? She has some excellent recommendations. One is to give yourself time. Don’t script things out. Don’t have a deadline. A second is to wander. Instead of using your smartphone and getting out a map, just drift a little. A simple one is to begin with questions, not assertions. If you’re going to a museum, think, “I wonder what painting will move me today?”

Then she has this interesting piece of advice — not only for our minds but socially — which is to watch out for language. As in, don’t label everything. Just let the experience come to you. When you first listen to a piece of music, don’t immediately look at how many likes it has or who performed it. Listen. When you’re on the trail taking in flowers, give yourself the experience before labeling them.

So I think that combination of giving yourself time, wandering without a script, asking questions, and watching out for language set good preconditions for awe.

Kevin: To wrap up, as we’ve hinted at throughout the interview, there’s a lot we still don’t know about awe. With that in mind, where do you want to take this research moving forward? What questions do you want to answer?

Keltner: One of them is for schools. At the Greater Good Science Center, we’ve got an education program. I’ll be working on awe principles for education because I think our kids need more awe. I’m also very interested in the meaning of awe and transcendence in different cultures. I’m working with a collaborator on going to indigenous cultures to see how they conceptualize it and, when it’s appropriate and done with respect, bringing principles of transcendence and awe into our understanding.

I’m grateful that you asked about visual art and music because it’s still a mystery how art does that. How in the world would art make me kinder to strangers?

The final one is moral beauty. This happened to me recently. I was on this noisy Berkeley street, and this young woman came out and handed $30 to his homeless guy. And just got goosebumps. Why? Interconnectedness. Ideals. Those are partial answers. There’s got to be a deeper explanation of how when we observe human goodness, it moves us to like-minded behavior. We don’t know the answer, and I think it’s a big question.

Kevin: I look forward to discussing with you whatever answers you find.

Keltner: That sounds great. It’d be an honor and a privilege.

Kevin: Where can people find you online to learn more?

Keltner: My book is available on Amazon and at local bookstores. I’d also recommend checking out the Greater Good Science Center at greatergood.berkeley.edu/. I have a Science of Happiness podcast with lots of content on awe. That’ll get them going, and then they can see where it takes them.

Learn more on Big Think+

With a diverse library of lessons from the world’s biggest thinkers, Big Think+ helps businesses get smarter, faster. To access Big Think+ for your organization, request a demo.

* This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.