The awesome power of awe: How this neglected emotion can change lives

- Awe has a rich history in the arts, but science has only recently delved into this perplexing emotion.

- Preliminary research suggests that awe-inducing experiences come with a bounty of benefits, from improved well-being to prosocial behavior.

- Real-world case studies, such as the experiences of astronauts working and living in space, show what awe can help us accomplish.

That’s awesome! The phrase has become ubiquitous in conversation. We use it to describe the imposing granite cliffs of El Capitan, the local JV team’s latest win, and a perfectly placed Parks and Rec meme on the office Slack channel. Like love—a word we use to express our feelings toward both our lifelong partners and a tasty burger—awesome has lost the gravitas of its origins. Where it once announced feelings of wonder, admiration, or even dread, today it means, “Yeah, pretty good.”

That’s fine. Etymology shows that words slide into new meanings to meet evolving cultural norms and needs. Sometimes words get fuzzier with age, others grow sharper, or we can even draft whole new ones. And awe may be undergoing a revival.

Psychologists have recently turned their attention to this artistically vaunted, if scientifically neglected, emotion, and they’ve found that awe-inspiring experiences may be worth more than the occasional burst of euphoria. They could prove to be powerful tools in overcoming many contemporary challenges, from issues of personal well-being to solving collective problems at a national or even global scale.

(Photo: John Fowler/Flickr)

What we talk about when we talk about awe

As anyone who has visited the Grand Canyon or a redwood forest can attest, we experience awe strongly in the presence of the natural world. But while idyllic landscapes are the most popular places to seek awe, they’re hardly the emotion’s only elicitor. We can experience awe when faced with the human-made—whether through the ancient Pyramids of Giza or a modern metropolis lit up at night. And granular can be just as awe-inspiring as the grand: Think the natural Fibonacci spiral of an ammonite shell or a perfectly brewed cup of coffee.

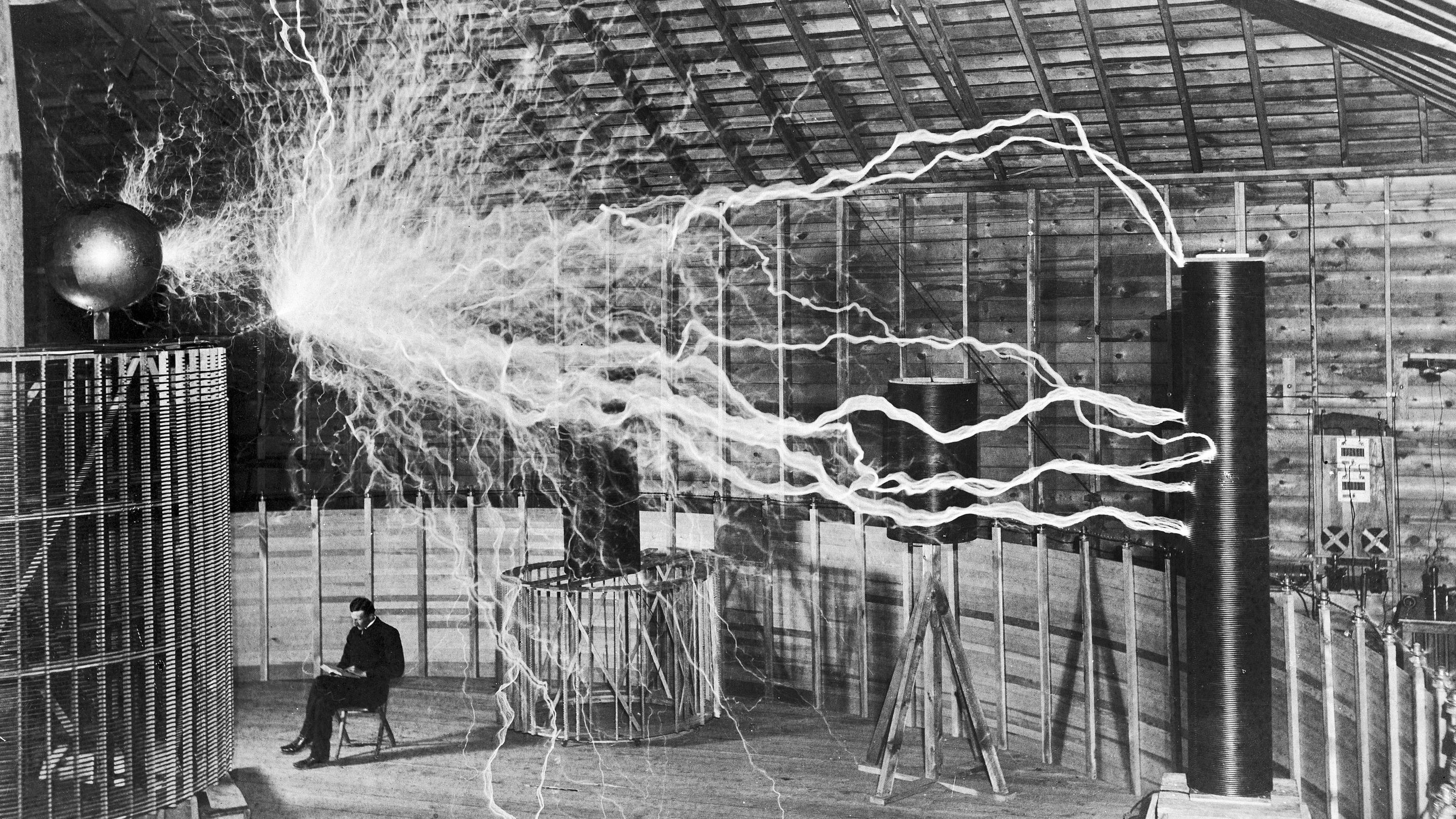

In fact, we don’t even have to discover awe in the world. We can create it through art, religious ceremony, and scientific discovery. To pick one of many examples, painters throughout history and across cultures have tried to capture the presence of awe, and while the masters have managed that feat, their results have been wildly different. Compare the tranquil awe of Sōami’s Zen Landscape of the Four Seasons to the sublime terror of J.M.W. Turner’s Snow Storm: Hannibal and His Army Crossing the Alps. (Which points to still another facet of awe: It can be frightful as well as wondrous. Hence, the origins of awesome’s equally weakened cousin, awful.)

Given that range, it’s little wonder science has had difficulty squeezing awe into a neat-and-tidy definition. But researchers are beginning to discover its contours, and that process began with a seminal 2003 paper by Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt. The psychologists proposed two qualities necessary for an experience to embody awe: vastness and a need for accommodation.

Vastness was defined as any experience of something that feels larger than the self or the everyday. While they may lead one to think bigger is better, the depths of vastness can be conceptual, as well. That’s why a favorite symphony or understanding the theory of evolution can leave someone as astounded as a view of Mt. Denali or walking the Great Wall of China. All four have the potential to connect people with something greater than themselves, something so vast it requires them to confront that greatness head-on.

And that leads to accommodation. Accommodation is one of those words that has a scientific meaning distinct from its casual use. In psychology, it represents the process by which people reevaluate their ideas or beliefs in the light of new experiences or information.

In other words, when awestruck, people begin to question their world perspective and potentially shift it as a result. The power of nature or the beauty in human accomplishment, these things diminish our egocentric importance and that requires us to revise our understanding of the world and our place in it.

Accommodation is why science has proven so inspirational to so many. You can’t learn that every star is a brilliant sun blazing trillions of miles away without questioning humanity’s place in life, the universe, and, well, everything. The same holds for religious experiences.

In this light, we can see how awe isn’t simply a high that we chase from one grand moment to the next. It’s potentially a cornerstone in our development, both as individuals and a species designed to learn and work together.

The awesome power of awe

By laying the scientific foundation, Keltner and Haidt kick-started exploration into awe’s benefits and pitfalls. And the shortlist of potential advantages is mind-blowing. In a 2018 white paper, the John Templeton Foundation and the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley explored the current research into awe. Their findings suggest that awe-fueled experiences might:

- Boost your mood.

- Decrease materialism.

- Increase humility and life satisfaction.

- Aid in developing critical thinking skills.

- Offer a greater sense of time.

- Improve health (such as lessening the markers of chronic inflammation).

In one study, researchers asked participants to walk outdoors, 15 minutes a day for eight weeks. The participants were told they had enrolled in an exercise study, but some were given instructions designed to engender awe—acts like observing natural details while walking in a forest. The participants who took these “awe walks” reported greater joy and displayed more intense smiles in their end-of-walk selfies.

Awe has also been suggested to increase our sense of community and drive us toward prosocial behaviors. In a series of six experiments published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, researchers looked to see if awe helped people integrate into social collectives. They asked participants to document their experiences in diaries, conducted lab experiments with awe-inspiring videos, and surveyed visitors at contrasting tourist locations (Fisherman’s Wharf versus a lookout at Yosemite Valley).

The results showed that awe-eliciting experiences created what psychologists call a “small-self perspective.” This reduced sense of self wasn’t connected to lower self-esteem or diminished self-worth. Rather, by reducing self-centered tendencies, the perspective aided participants in feeling connected to a greater whole and an increased need for collective engagement.

“While we’re feeling small in an awe moment, we are feeling connected to more people or feeling closer to others. That’s awe’s purpose, or at least one of its purposes,” Yang Bai, one of the paper’s authors and a researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, told Greater Good Magazine.

And the awe walk study found a similar result. Remember those after-walk selfies? The researchers found that the awe-inspired walkers took pictures that presented them as smaller and more integrated with their natural surroundings. There was less self in the selfies.

Another paper published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, this one collecting the results of five experiments, looked directly at the relationship between awe and the small self. Taken together, its researchers argue that awe increases prosocial behaviors such as generosity and ethical decision-making while lessening a sense of entitlement.

“People can easily ignore the benefits of feeling small, of feeling humble. But we all feel the need to feel connection to other human beings, and awe plays a very important role in that,” Bai added.

I can see our home from here

It should be noted that the science of awe is in its infancy. Few, if any, of these studies have been replicated, and their results represent only the preliminary steps in our understanding. Researchers haven’t yet delved deeply into, for example, awe’s therapeutic use cases or its potential pitfalls.

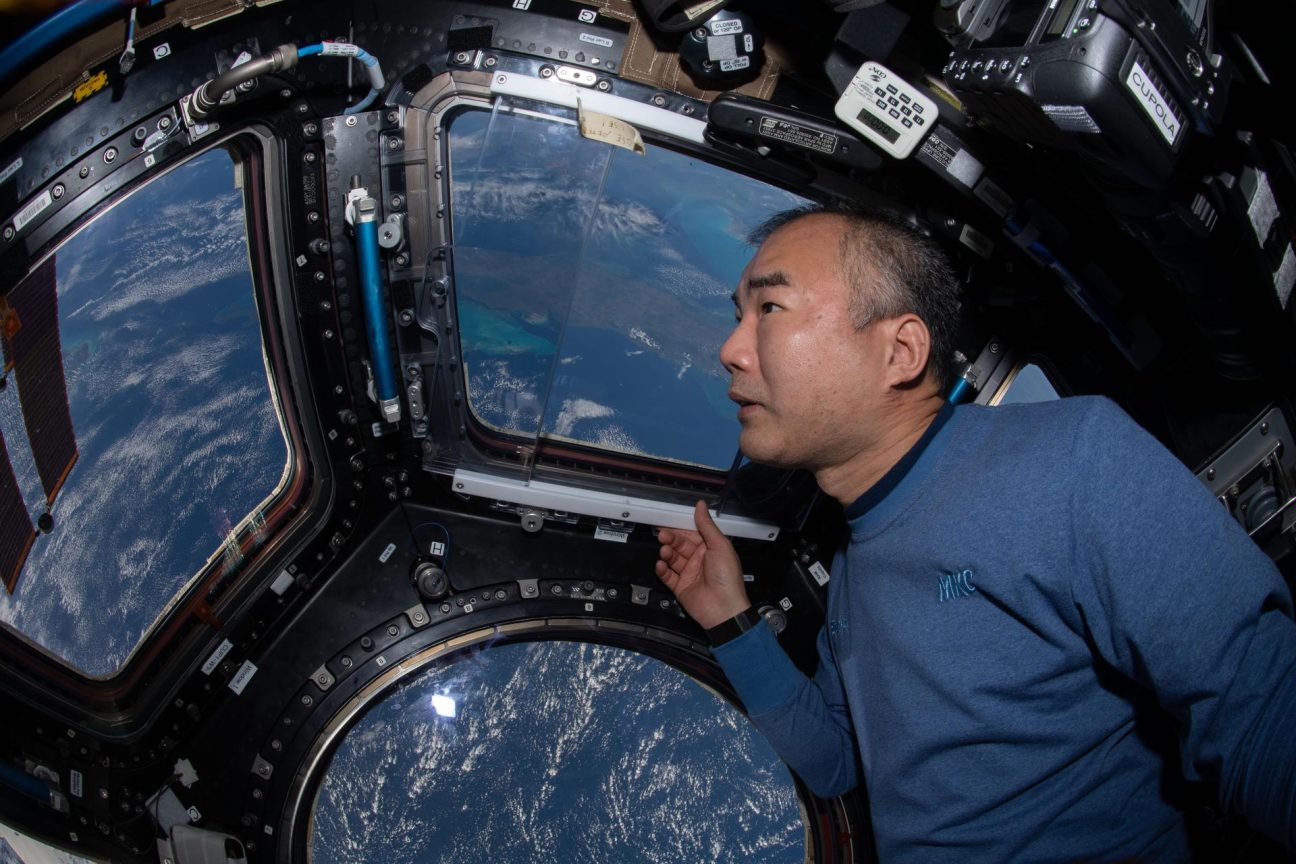

Even so, the current research does support the lived experiences of those who have enjoyed perhaps the most awesome privilege the modern world can offer: seeing the Earth from space.

In a Big Think+ interview, retired astronaut Leland Melvin described his experiences working and living aboard the International Space Station. Seeing his home planet from space, working in harmony with people from all over the world, Melvin developed a profound sense of awe. That led him to a perspective shift.

I got this cognitive shift that I felt—looking at the planet with no borders and one race, the human race. When I got home, it made me feel so much more connected with everyone around me.

Leland Melvin

He added: “Whether it’s someone in this tribe or that tribe, I felt that we had a common purpose to help keep our humanity going forward. We have all these things, climate change and race, I mean, just all the -isms that you can think about on the Earth. But this perspective gave me a path to share this experience of this travel, this journey that I took with others. And it pulled them in.”

This small-self shift is quite common among astronauts faced with the vastness of our pale blue dot from space. Retired astronaut Ron Garan calls it the “orbital perspective.” It also goes by the “overview effect.” Whatever the name, the trigger for this change in perspective is a sense of awe.

As neuroscientist Andrew Newberg describes it: “The brain itself is capable of taking in the overview experience and converting such an overwhelming concept into our behaviors and thoughts. Individuals who have had the overview experience feel a breaking down of boundaries and a sense of the interconnectedness and preciousness of the Earth and all those who live on it.”

The takeaway lessons from those who have experienced the overview effect are different, but they all seem to center on the belief that we can tap into awe to create a sense of unity and wholeness to solve collective problems.

For Melvin, this perspective intricately links to curiosity, another human-centric drive. Such awe leads us to satiate our curiosity, which further propels us to exploration (recall the role of accommodation). And space exploration, Melvin notes, has improved the lives of people on Earth. To tackle space, NASA developed things like pacemakers and smoke detectors.

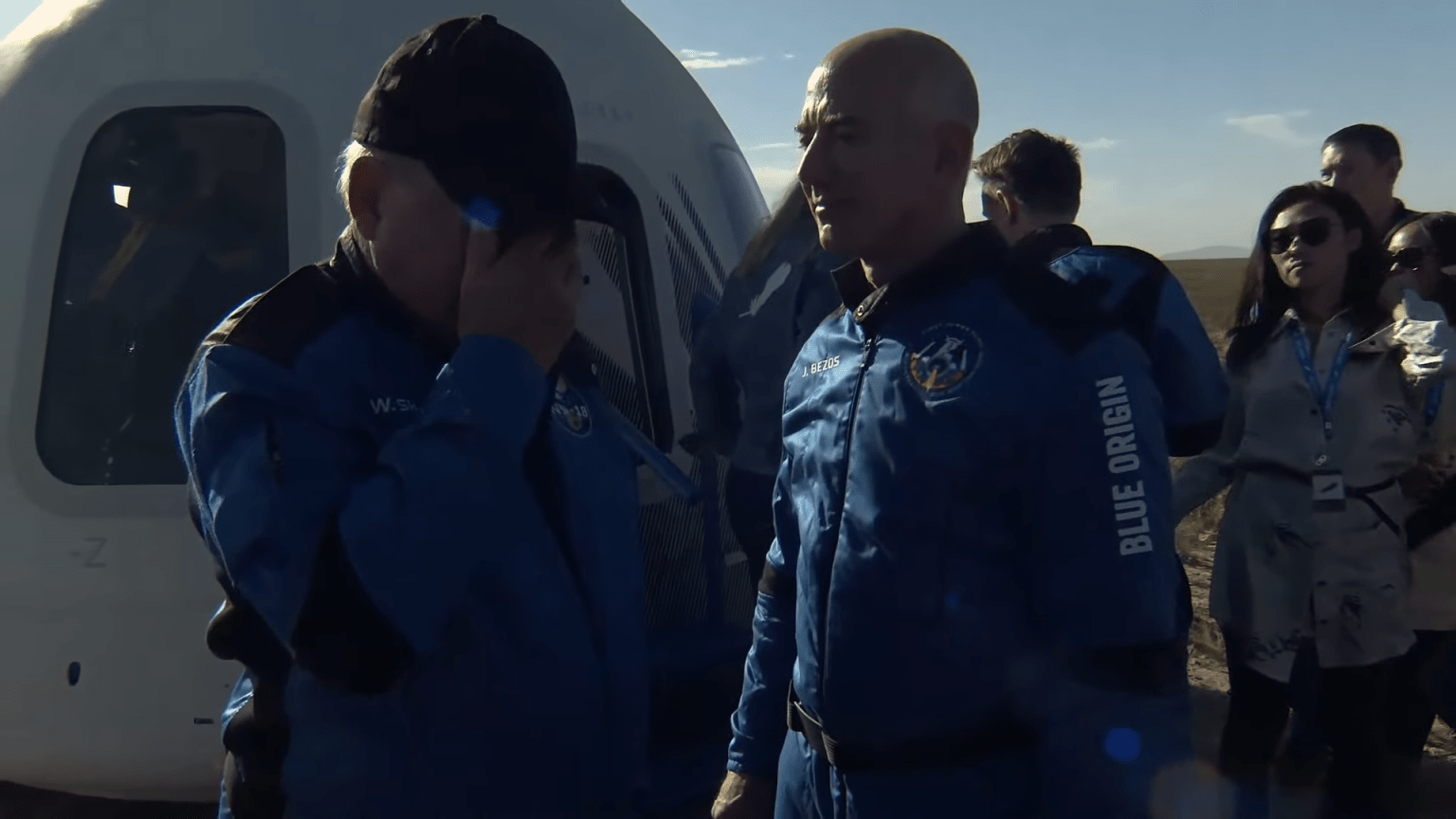

Even William Shatner’s visit to space had a profound effect on the 90-year-old actor. For him, the awe of space proved a reminder of how precious and precarious life on Earth is. As he said when he returned: “I can’t even begin to express. What I would love to do is to communicate, as much as possible, the jeopardy, the moment you see the vulnerability of everything;, it’s so small. This air, which is keeping us alive, is thinner than your skin. It’s a sliver. It’s immeasurably small when you think in terms of the universe.”

Conversely, Garan sees a much loftier ambition for awe. His experiences aboard the ISS showed him how well people from various backgrounds can work together toward a single goal. He believes this orbital perspective can scale to help us solve the global problems facing us today, such as climate change and feeding the hungry.

If we can promote awe and recognition of individual smallness, he believes, we can build the trust, relationships, and platforms necessary to begin solving problems on a global scale.

Can awe be a cross-cultural motivator for change?

Of course, awe as a linchpin for such global collaboration only works if the emotion is universally shared. As mentioned already, we’re a long way from establishing that. But the information we have so far seems promising.

In their paper, Yang Bai and her co-researchers looked at differences in awe between both Chinese and American participants. The researchers found that Chinese participants—who hail from a more collectivist culture—chose more experiences involving people over nature. Additionally, Americans—who hail from a more individualistic culture—showed larger “small-self” effect sizes. Nonetheless, all participants showed a link between awe and improved social relationships.

And as Melvin explained in his interview, the overview effect seems to take hold of astronauts, regardless of culture or nation of origin.

Should awe not live up to the current hype, it’s still worth cultivating in your life and the lives of others. Seeking out awe-inspiring experiences at work and in your life will likely provide many fringe benefits—such as exercise, exposure to nature, new experiences, opportunities to learn, and so on. If it proves a placebo emotion, that’s a terrific placebo effect. And if not, you may discover a better use for the next time you say, “That’s awesome!”

Watch more from these experts on Big Think+

Foster awe and a culture of lifelong learning with lessons on Big Think+. Our e-learning platform brings together more than 350 experts, academics, and entrepreneurs to help your organization develop the skills necessary to succeed in the 21st-century.

Join astronauts Leland Melvin, Chris Hadfield, and Scott Parazynski for such awesome lessons as:

- Get to Mission Success

- Reduce Stress by Improving Your Readiness

- Communicate Across Cultures: Lessons Learned Aboard the International Space Station

- An Astronaut’s Guide to Risk Mitigation: Predict the Consequence and Probability of Events

Learn more about Big Think+ or request a demo for your organization today.