Sorry, the EmDrive doesn’t work

- The proposed EmDrive captured the public’s imagination with the promise of super-fast space travel that broke the laws of physics.

- Some researchers have detected thrusts from the EmDrive that seemed to prove its validity as a technology.

- A new, authoritative study says, no, those results were just “false positives.”

Now it seems that, yep, it was too good to be true. Scientists at Dresden University of Technology (TU Dresden) appear to have conclusively proven that the EmDrive does not, in fact, produce any thrust. They provide some compelling evidence that small indications of thrust in previous research were simply false positives produced by outside forces.

How the EmDrive is supposed to work

In the EmDrive, says the company that owns rights to the invention, “Thrust is produced by the amplification of the radiation pressure of an electromagnetic wave propagated through a resonant waveguide assembly.” In simpler words, trapped microwaves bounce around a specially shaped enclosed container, producing thrust that pushes the whole thing forward.

They also assert that while the EmDrive is not exactly on speaking terms with Newton’s Third Law, the company says it’s perfectly in line with the second one:

“This relies on Newton’s Second Law where force is defined as the rate of change of momentum. Thus, an electromagnetic (EM) wave, traveling at the speed of light has a certain momentum which it will transfer to a reflector, resulting in a tiny force.”

Interest in the EmDrive has been understandable considering what it was supposed to do. Speaking to Popular Mechanics last year, Mike McCulloch, the leader of DARPA’s EmDrive investigation, describes how the engine could “transform space travel and see craft lifting silently off from launchpads and reaching beyond the solar system.” He mentioned his excitement at being able to get from here to Proxima Centauri — 4.2465 light years away — in just 90 human years.

It doesn’t work. Yes it does. No, it doesn’t.

DARPA, part of the U.S. Department of Defense, is only one of the organizations investigating the claims made for the EmDrive. In 2018 the agency invested $1.3 million to study the device in research that will be wrapping up this May barring any significant last-minute breakthroughs.

Teams from all over the world have been testing Shawyer’s idea since it was introduced and releasing often contradictory test results. This may have to do with the fact that teams detecting any EmDrive thrust at all have reported vanishingly small amounts of it, measured in milliNewtons (mN). A mN equals about 0.00022 pounds of force.

As Paul Sutter wrote in an op-ed for Space.com:

“Ever since the introduction of the EmDrive concept in 2001, every few years a group claims to have measured a net force coming from its device. But these researchers are measuring an incredibly tiny effect: a force so small it couldn’t even budge a piece of paper. This leads to significant statistical uncertainty and measurement error.”

For a sense of how minuscule these results are, consider that the possible thrust force reported by NASA in 2014 of 30-50 micro-Newtons is roughly equivalent to the weight of a big ant. Chinese researchers have claimed detection of 720 mN in their tests. That would be 72 grams of thrust. An iPhone 11 with a case weights 219 grams.

Too small to stand out against background noise

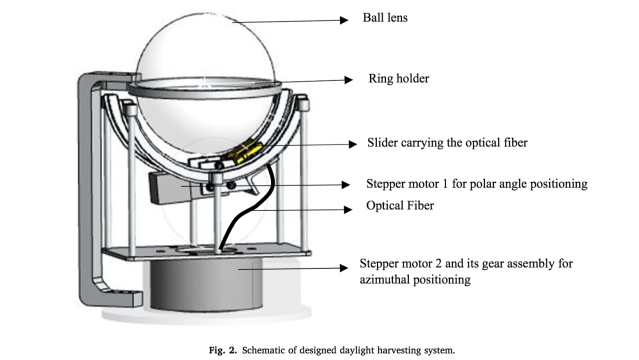

These tiny amounts of EmDrive thrust lie at the heart of what the TU Dresden researchers are saying: The effects are simply too small to rule out effects that don’t really come from the EmDrives at all. The researchers have just published three papers. The title of one “High-Accuracy Thrust Measurements of the EmDrive and Elimination of False-Positive Effects” tells the story. The other two studies are here and here.

When the UT Dresden team turned on their EmDrive based on NASA’s EmDrive, they, too witnessed tiny amounts of apparent thrust.

However, says Martin Tajmar of UT Dresden to German media outlet GreWi, they soon realized what was going on: “When power flows into the EmDrive, the engine warms up. This also causes the fastening elements on the scale to warp, causing the scale to move to a new zero point. We were able to prevent that in an improved structure.”

Putting the kibosh on other researchers’ results, the authors of the studies write:

“Using a geometry and operating conditions close to the model by White et al. that reported positive results published in the peer-reviewed literature, we found no thrust values within a wide frequency band including several resonance frequencies. Our data limits any anomalous thrust to below the force equivalent from classical radiation for a given amount of power. This provides strong limits to all proposed theories and rules out previous test results by more than three orders of magnitude.”

This would seem to be the definitive end of the EmDrive story.