Human CRISPR Trials Will Happen in 2018. They’ll Look Like This.

“Every new and hot biomedical technology usually undergoes an inflated expectations phase,” Alexey Bersenev, director of the Advanced Cell Therapy Lab at Yale-New Haven Hospital tells MIT Technology Review. When CRISPR-Cas9 was first introduced in 2014, the sky seemed to be the limit when it came to all the genetic issues it could conceivably repair. As with any potentially life-saving medical breakthrough, the hopes of many leaped, quite naturally, to a future in which CRISPR-Cas9 was readily available and in wide use. CRISPR-Cas9 still retains that tremendous promise, but the reality is that that these things take time. China has a number of human CRISPR trials underway, though no results have yet been made available. And now, finally, human trials are about to get underway in Europe and the U.S.

The targets of the U.S. and European trials are two genetic blood disorders that ruin hemoglobin: sickle-cell anemia and beta thalassemia. Sickle-cell disease is among the most common genetic maladies, with millions affected worldwide. When someone has sickle-cell, painful blood-vessel blockages can occur, as can anemia, infections, and eye problems. Sickle-Cell sufferers are also at increased risk of strokes, and heart, kidney, and liver damage.

The sickle cell, shaped like a farmer’s sickle, is to the left of four normal blood cells. (OPEN STAX COLLEGE)

Major beta thalassemia, also called “Cooley’s anemia,” develops shortly after birth and is a progressive condition that prevents an infant from developing normally, best by feeding problems, fever, and intestinal distress, including diarrhea.

The Europe and U.S. treatments involve two companies. CRISPR Therapeutics, founded by Emmanuelle Charpentier, one of the co-inventors of CRISPR-Cas9, has asked regulators in Europe for permission to treat beta thalassemia, hopefully during 2018. They also plan to request approval within the next six months from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for sickle-cell treatments. Researchers at Stanford University School of Medicine are also planning to begin sickle-cell CRISPR therapy at their Center for Curative and Definitive Medicine, and intend to seek permission from the FDA in 2018.

There’s reason to take baby steps with such a powerful technology — just ask Jennifer Doudna, CRISPR-Cas9’s other co-inventor — with technical and ethical issues to be addressed prior to editing genes for reinfusion into living patients.

There have been other attempts at beginning clinical trials that have stalled. The University of Pennsylvania last year received permission from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the FDA to begin CRISPR treatments for melanoma, sarcoma, and multiple myeloma in 2017. They have yet to get underway; it’s not clear why. Editas Medicine’s planned clinical trials of a treatment for inherited blindness hit a manufacturing bottleneck and has been postponed. Intellia Therapeutics hasn’t announced any trials yet.

CRISPR Therapeutics and Stanford are approaching the problematic hemoglobin in sickle cell and beta thalassemia in different ways, though both will be taking stem cells from patients’ bone marrow.

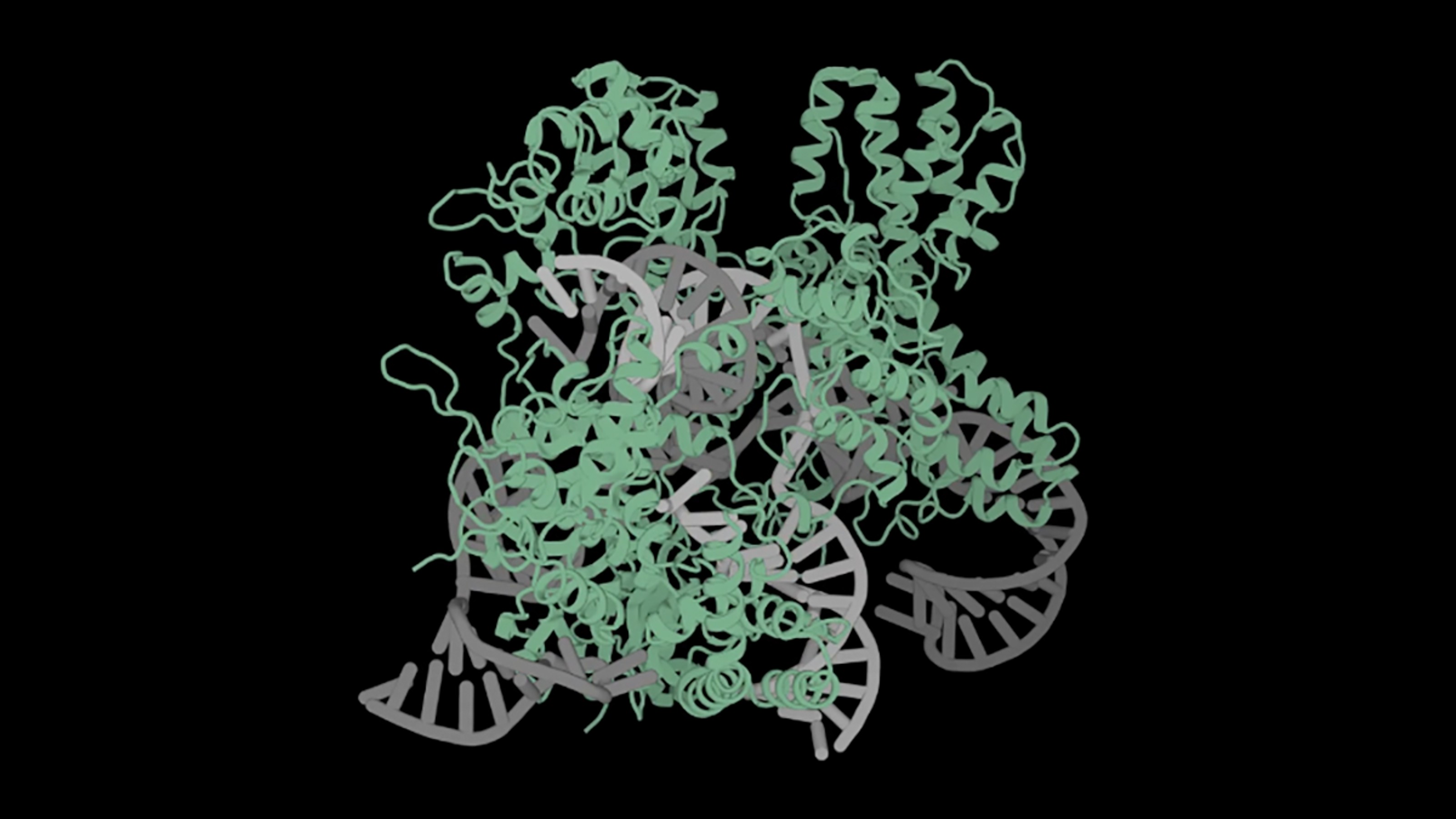

Hemoglobin (MURTADA AL MOUSAWY)

CRISPR Therapeutics plans to “make a single genetic change that is designed to increase fetal hemoglobin levels in a patient’s own blood cells. The edited cells are then reinfused and are expected to produce red blood cells that contain fetal hemoglobin in the patient’s body, thereby overcoming the hemoglobin deficiencies caused by the disease.” Stanford plans to repair the defective hemoglobin using CRISPR before returning it to patients’ bodies — since sickle cells live only about 10-20 days, and healthy cells from 90 to 120 days, it’s their expectation that healthy cells will soon be in the majority. This matters because patients whose sickle cell counts are below 30% have no symptoms.

It may not yet the gene-editing world we may have imagined when we first learned of CRISPR-Cas9, but it looks like 2018 may be the year that future finally gets underway at last.