How MIT’s VR environment is saving drones from crashing to death

Drones, or unmanned vehicles that fly through the air, are used by civilians and the military alike. While the military uses drones to get to areas that are too difficult or risky for humans, commercially drones are used for photography, research, and even racing.

According to Gartner, a research firm, drone sales grew 60% from 2016 to 2017 to $2.2 million, with revenue up 36% to almost $4.5 billion. With estimates of U.S. drone sales doubling year over year, millions of hobbyist drones are now in homes. Per year, sales of drones are clocking in around $200 million, and an average drone from DJI, the leading commercial drone manufacturer, is between $500 to $1,000.

Drones are essential to many fields, such as businesses, the government, and certain industries, like agriculture. Important fields with promising drone-usage include:

-

Photographing

-

Journalism

-

Film

-

Express delivery (think Amazon)

-

Supplying necessities in disaster zones

-

Search and Rescue (thermal sensor drones)

-

Mapping of inaccessible terrains

-

Safety inspections

-

Crops (monitoring, delivery of resources, etc)

-

Cargo transport

-

Law enforcement, like border patrol

-

Strom tracking

With so much money being spent on the development of drones, testing their safety, abilities, and durability are paramount to the industry’s success. After all, with a $500+ price tag, replacing them isn’t cheap. Due to the cost of repairing and replacing drones, a better way to train autonomous drones was needed. That’s where MIT comes in – with a VR training system named “Flight Goggles.”

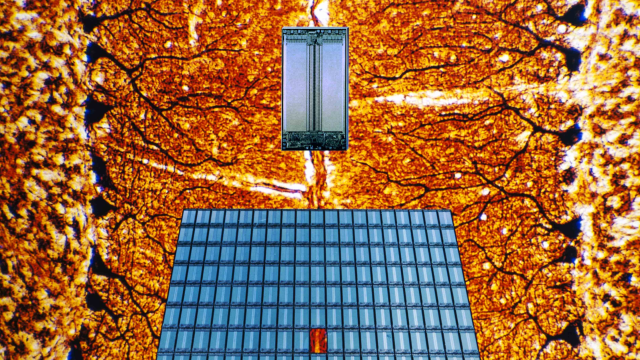

The VR environment creates indoor obstacles for the drones to fly around, without actually needing to have those obstacles be indoors – the testing facility can remain empty, while the drone sees “real” obstacles. Additional benefits of “Flight Goggles” are endless, as virtual testing facilities in which any environment or condition can be subbed in for the drones to train.

“We think this is a game-changer in the development of drone technology, for drones that go fast,” Associate Professor Sertac Karaman said in an MIT blog post. “If anything, the system can make autonomous vehicles more responsive, faster, and more efficient.”

Currently, if a researcher wants to fly an autonomous drone, they must set up in a large testing facility in which physical obstacles, like doors and windows, must be brought in, as well as large nets to catch falling drones. When they do crash (and they do) the cost of the project and the development timeline both increase, due to repairs and replacements.

“The moment you want to do high-throughput computing and go fast, even the slightest changes you make to its environment will cause the drone to crash,” said Karaman. “You can’t learn in that environment. If you want to push boundaries on how fast you can go and compute, you need some sort of virtual-reality environment.”

Researchers use a motion capture system, electronics, and an image rendering program to transmit the images to the drone. The images – which are processed by the drone at about 90 frames per second – are all thanks to circuit boards and the VR program the drone operates within.

“The drone will be flying in an empty room, but will be ‘hallucinating’ a completely different environment, and will learn in that environment,” Karaman explains.

During the course of 10 test flights using the VR program, the drone (which files at around 5 miles per hour) successfully flew through a virtual window 361 times, only crashing three times – which doesn’t impact the development of costs. And as the window was virtual, nobody was hurt by glass. So it’s a win-win for enthusiasts, researchers, professionals, and everyone in between.