sleep

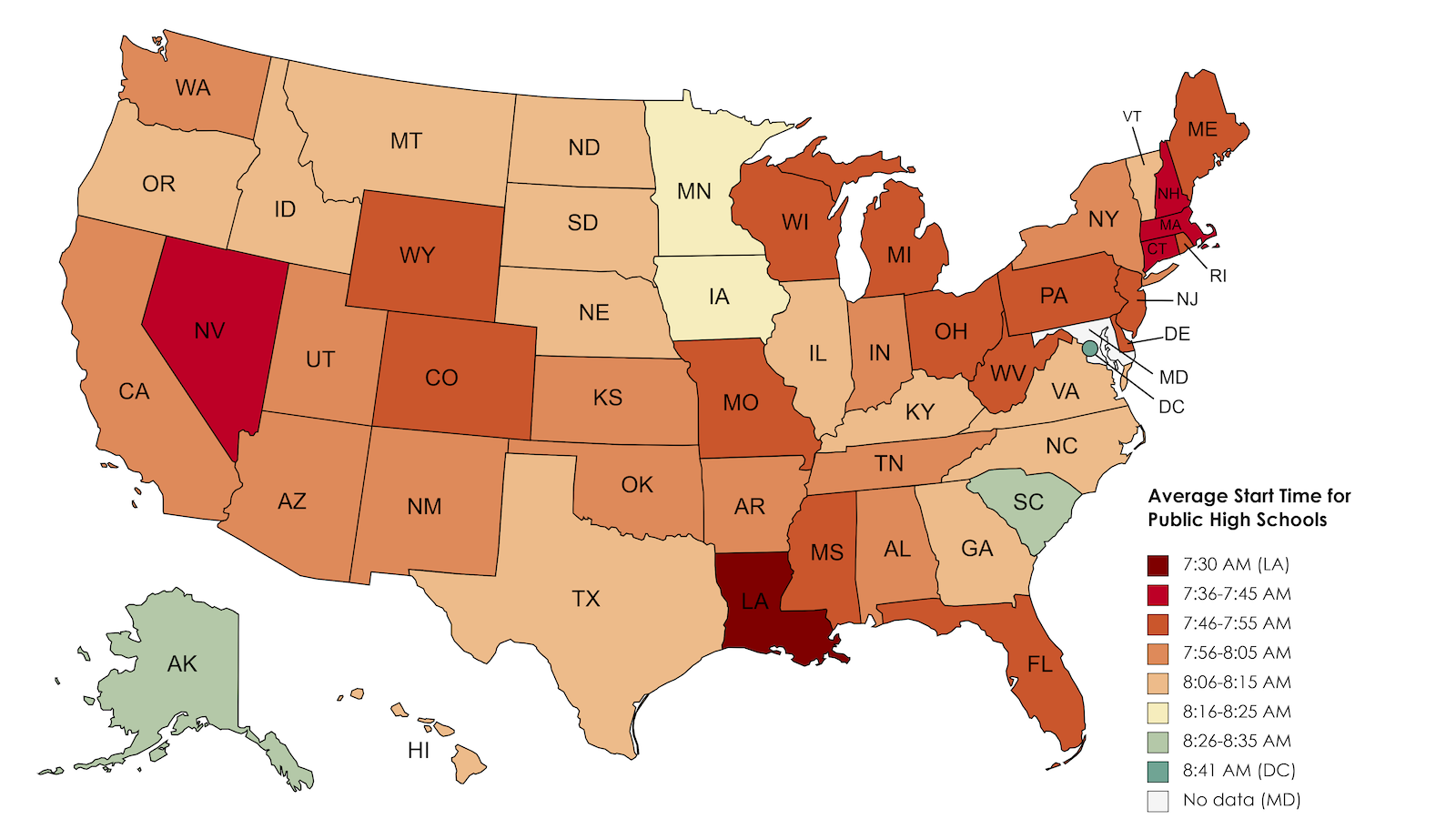

In Louisiana, high school starts at 7:30 am. Research shows that is at least an hour too early.

How the brain decides what to store and what to forget.

A textbook pregnancy consists of three trimesters. The baby develops at a relatively predictable rate during this time, from pomegranate seed to avocado to watermelon. And mom’s body adapts accordingly […]

Are you getting a full 8 hours?

Participants were asked to complete a simple attention task as well as a more challenging “placekeeping” task.

Neuroscience explains terrifying ordeals, from out-of-body experiences to alien abductions.

Dreams are weird. According to a new theory, that’s what makes them useful.

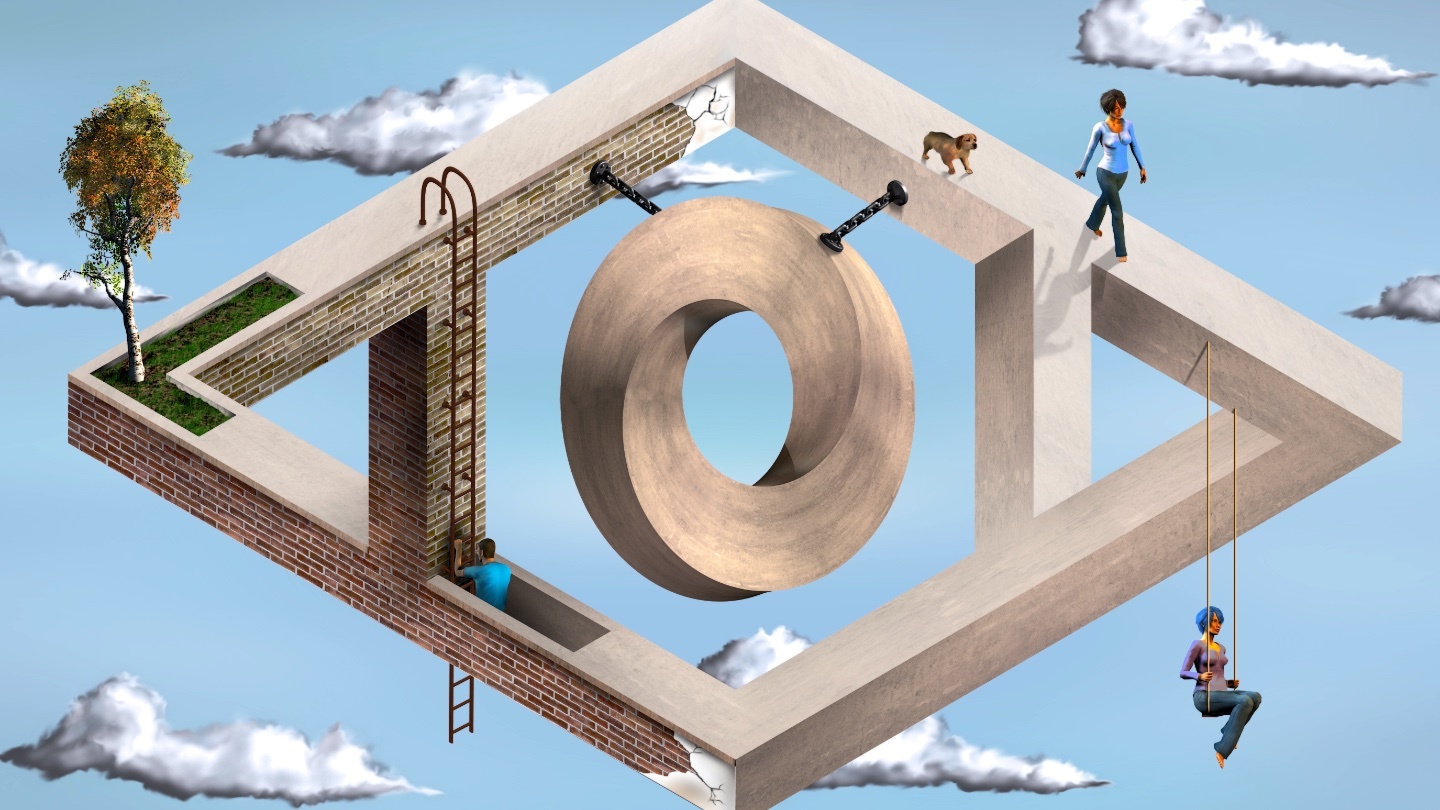

We all know that work-life balance can be difficult, but do we make it harder on ourselves by how we choose to conceptualize the idea? More specifically, is the concept […]

New studies show that some people can hear and respond to questions while dreaming.

Heard about the phenomenon of FNE, or ‘first night effect’?

A new theory suggests that dreams’ illogical logic has an important purpose.

Getting plenty of sleep just became even more important.

The study sheds new light on the relationship between sleep and mental health.

A new study of nurses shows the importance of sleep—and staying aware on the job.

A team at the University of Basel discovered a connection between antidepressants and REM sleep.

Insomnia is the product of mental or emotional pressure.

The goal of this large-scale study was to provide actionable information on how to avoid depression or decrease depressive symptoms.

Restflix has over 20 personalized channels for optimal sleep.

There are several things both men and women can do to actively boost low libido, according to research.

Chronic irregular sleep in children was associated with psychotic experiences in adolescence, according to a recent study out of the University of Birmingham’s School of Psychology.

Living like a genius and finding ways to “optimize” sleep is not necessarily good for your health. Here’s why.

▸

8 min

—

with

Light therapy might help your natural circadian rhythm and even stave off seasonal depression.

New research establishes an unexpected connection.

How to manage your time so you can actually accomplish what you want to.

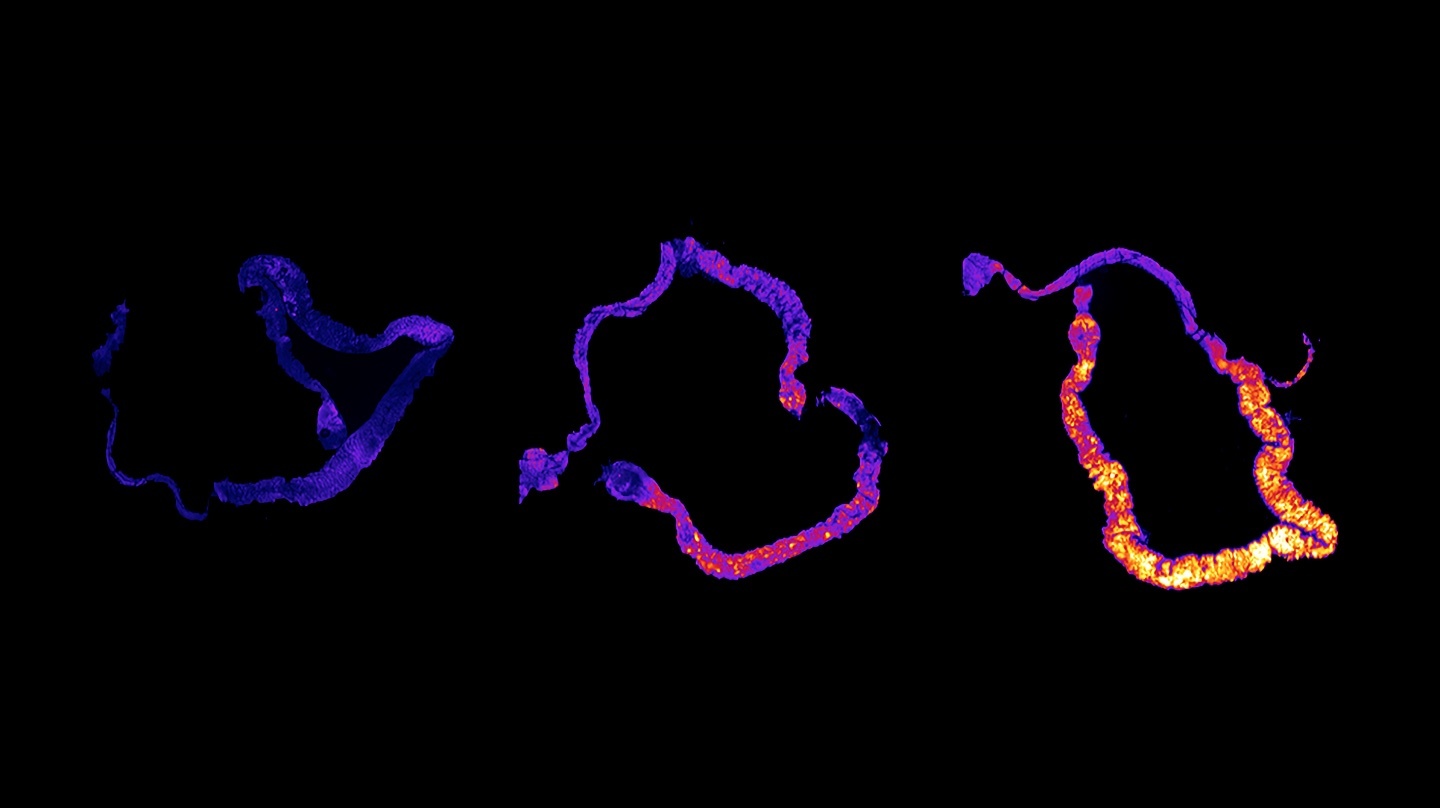

Brain-computer interfaces give scientists their closest look so far at what the human brain does while we’re asleep.

Thankfully, there are ways to combat mental and physical fatigue, even in isolation.

Ever had trouble finding reason to get out of bed? Marcus Aurelius has some advice for you.

A new study suggests that the type of alarm clock you use might affect the severity of sleep inertia you experience.