peace

The world’s 10 most affected countries are spending up to 59% of their GDP on the effects of violence.

The AI constitution can mean the difference between war and peace—or total extinction.

▸

5 min

—

with

What is human dignity? Here’s a primer, told through 200 years of great essays, lectures, and novels.

The ability to interact peacefully and voluntarily provides individuals a better quality of life.

▸

5 min

—

with

Despite potential good intentions, interventionist policies are often viewed by classical liberals as violations of individual freedoms.

▸

6 min

—

with

As a moral and political philosophy, classical liberalism lays a framework for the good society.

▸

8 min

—

with

Does the President get to decide when to ignore the law?

▸

6 min

—

with

Researchers believe that war exacerbates climate change, threatening the environment and making future wars more likely.

A second step is to determine where violence concentrates and who is most at risk.

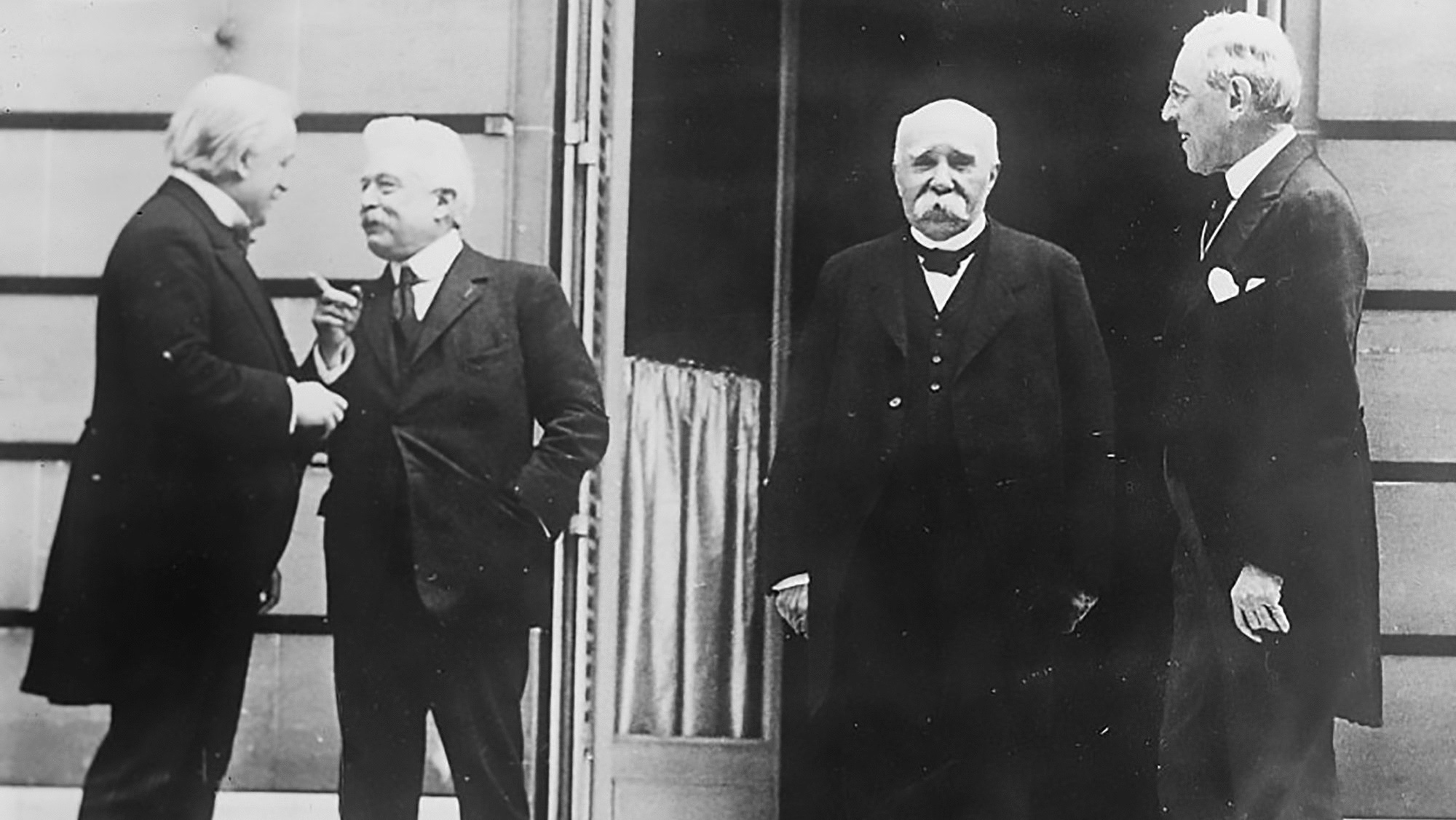

In 1919, Woodrow Wilson attempted to rally the U.S. behind the League of Nations. His failure suggested the way forward.

A study of 323 uprisings against repressive regimes yields stunning insights.

Pulitzer Prize-winner Jared Diamond explains why some nations make it through epic crises and why others fail.

▸

4 min

—

with

Changing people’s minds isn’t how we end polarization. Tolerance is the gateway to peaceful coexistence.

▸

3 min

—

with

Policy advisor Simon Anholt believes the question we should ask is, which country is the “goodest”?

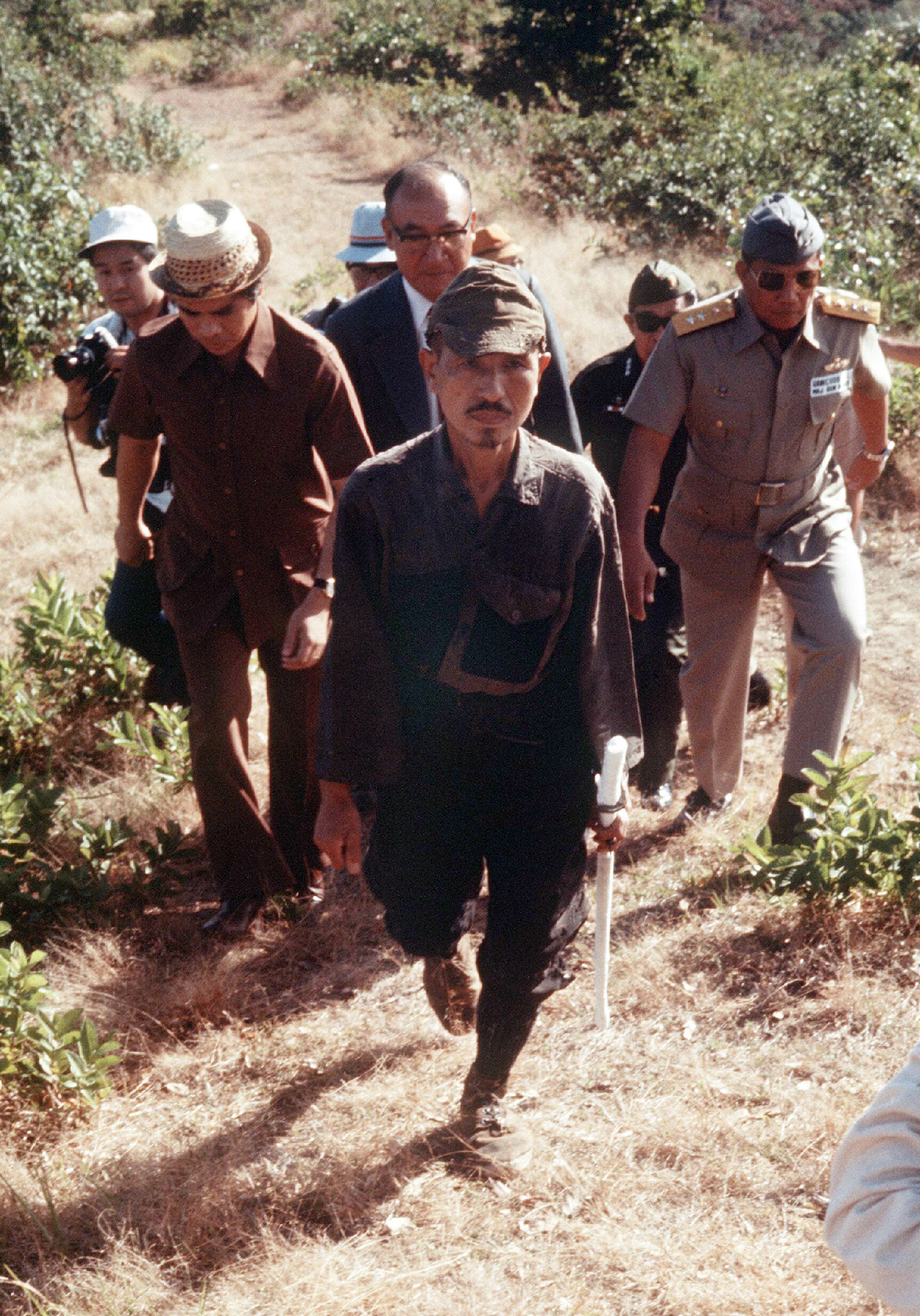

For the Japanese in World War II, surrender was unthinkable. So unthinkable that many soldiers continued to fight even after the island nation eventually did surrender.

Following World War I, President Woodrow Wilson nearly died trying to ensure world peace.

The incredible story of a scientist who survived gulags, fighting to change his country and physics.

Want to empower social change? Break bread, literally, with the so-called enemy.

▸

5 min

—

with

Feminism simply means equal rights for men and women.

▸

5 min

—

with

A religious person without a sense of humor? That’s a dangerous combination.

▸

2 min

—

with

Millions of Muslims marched to Karbala, Iraq even after suicide bombing and continued threats by ISIL. The Arbaeen pilgrimage continues to be a show of religious freedom.