logic

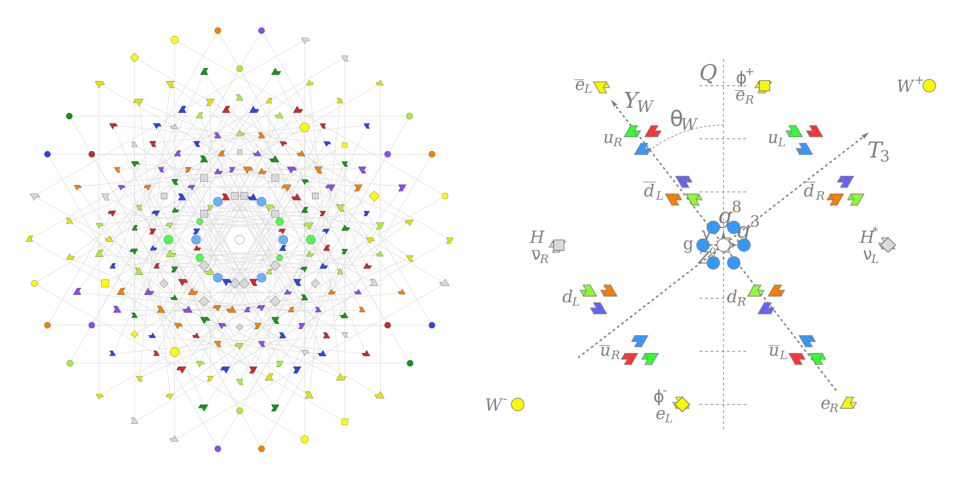

Why human attempts to mechanize logic keep breaking down.

Research suggests that experience may matter more than innate ability when it comes to a sense of direction.

According to the legendary investor, the best method is a blueprint for “extreme success.”

If you’ve found yourself befuddled by extraordinary scientific-sounding claims, you’re not alone. But this centuries-old lesson can help.

The space‑specific neurons in the owl’s specialized auditory brain can do advanced math.

Walter Pitts rose from the streets to MIT, but couldn’t escape himself.

It’s a useful fiction — but it’s still fiction.

Chess could perhaps be the ultimate window through which we might see how our mental powers shift during our lives.

More than 90 percent of people make a mistake on this test.

Take a closer look at the different types of reasoning you use every day.

“For every PhD there is an equal and opposite PhD.”

We could even benefit from more whataboutisms — if they’re used properly.

Why, exactly, don’t you trust that person’s opinion?

Even the dictionary doesn’t get the definition right.

A new technique for analyzing networks can tell who wields soft power.

Since at least 600 BC, people have been mesmerized by the concept of the infinite.

The base rate fallacy may help to explain low reproducibility in various fields of science.

Pseudoscience is science’s shadow.

A bat and a ball cost $1.10 in total. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

In a new book, an MIT scholar examines how game-theory logic underpins many of our seemingly odd and irrational decisions.

People believe that slow and deliberative thinking is inherently superior to fast and intuitive thinking. The truth is more complicated.

It took a series of ingenious experiments in the 20th century to uncover some of our biggest cognitive biases.

More than a decade ago, Armenia made chess a required subject in school because it teaches kids how to think and cope with failure. The U.S. should follow suit.

Wordle activates both the language and logic parts of our brain and give us a nice boost of dopamine, whether we win or lose.

What was once an art form has been drained of color and personality by ruthless algorithms. Can we make chess human again?

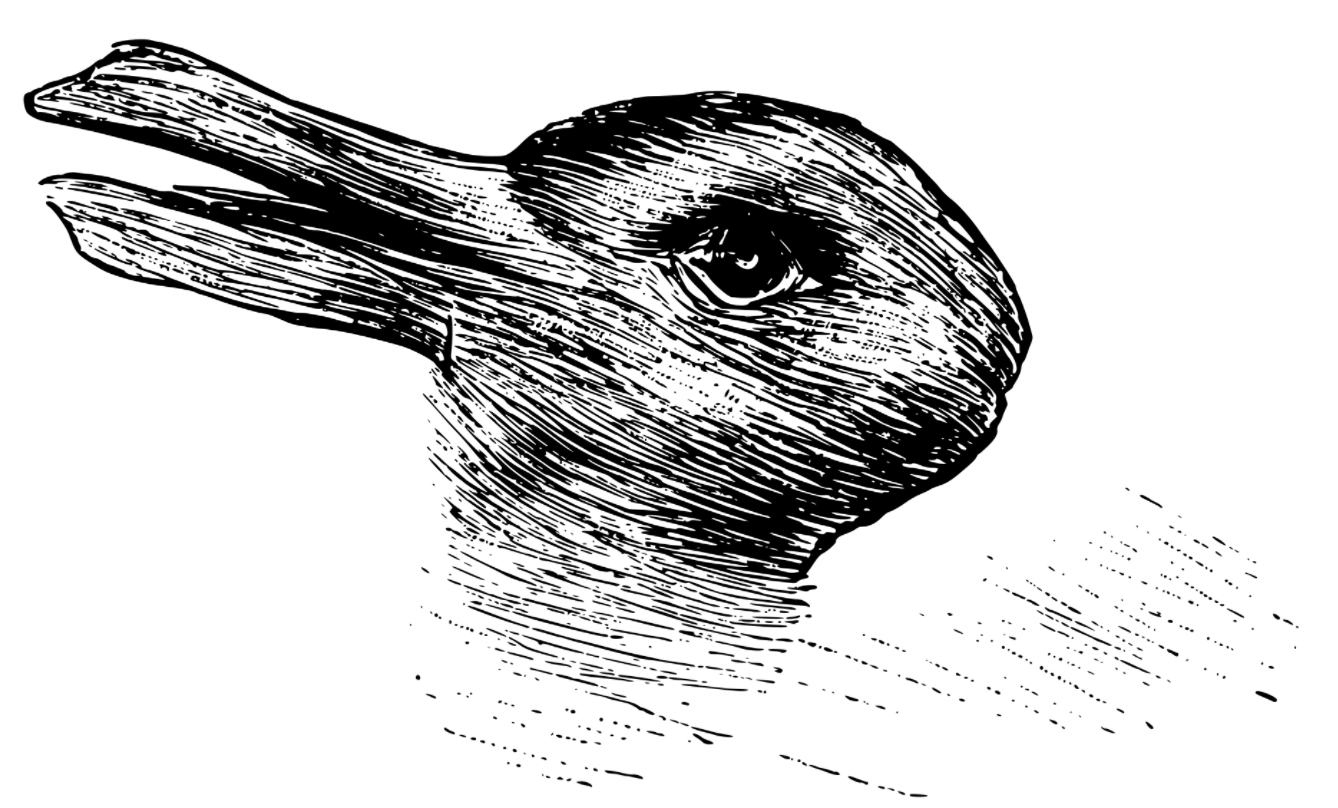

Most things in the world can be seen in surprisingly different ways.

Setting resolutions for the new year means you think the future is up to you — but is it?

Truth needs us to define the rules, grammar, and criteria for true statements. But can we do this within language itself?

Dedicated circuits evaluate uncertainty in the brain, preventing it from using unreliable information to make decisions.