Freedom

Instead of insisting that we remain “free from” government control, we should view taking vaccines and wearing masks as a “freedom to” be a moral citizen who protects the lives of others.

Quarantines are worth the trouble to keep the next pandemic at bay but they need to be applied intelligently.

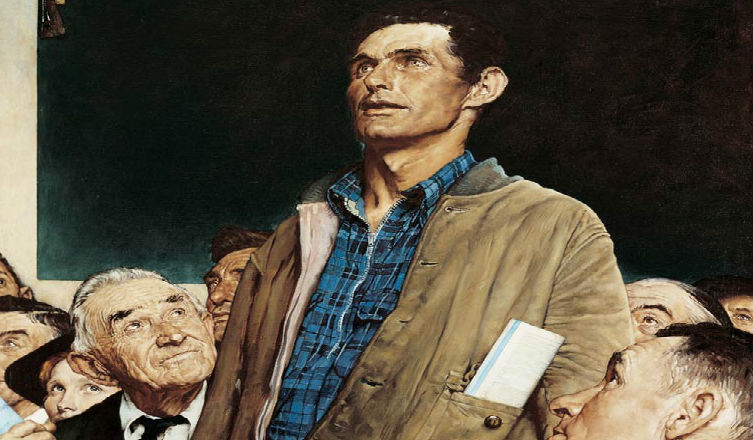

Have you been feeling like democracy is in trouble lately? According to this report, you’re right.

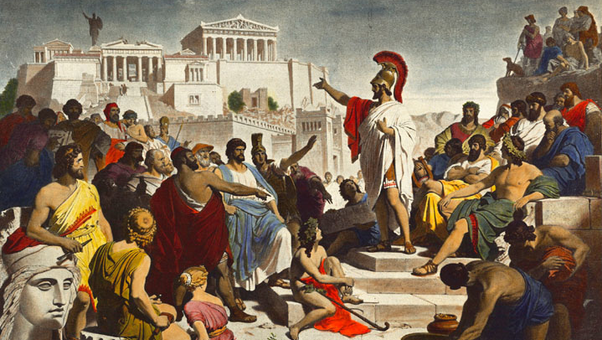

Many great minds have plenty of bad things to say about democracy, but what about the people who think it is great?

While we often criticize the humanities for not providing an education that leads directly to employment, one philosopher argues they have an even more important role to play in our societies.

Insert dial-up noise here. If you’re not concerned about what’s about to happen with net neutrality, you’re not paying attention.

Here’s how the government improves your life without you knowing it.

▸

8 min

—

with

Storied skills and a musical analogy might help us update the logic of “virtue ethics.” In life, as in jazz, freedom without skills results in a lot foolish noise.

Before we had the right to vote, we had the right to protest, says journalist Wesley Lowery.

▸

6 min

—

with

Millions of Muslims marched to Karbala, Iraq even after suicide bombing and continued threats by ISIL. The Arbaeen pilgrimage continues to be a show of religious freedom.