economics

Big Think spoke with historian Marc-William Palen about the egalitarian aims of the free-trade movement in past centuries.

If you’ve looked for a job recently, you may have encountered the personality test. You may also have wondered if it was backed by scientific research.

If we took the values and principles of cooperation to the next level, we could effectively tackle many crises.

For centuries, the only way to travel between the Old and New World was through ships like the RMS Lusitania. Experiences varied wildly depending on your income.

The Knights Templar were not only skilled fighters, but also clever bankers who played a crucial role in the development of Europe’s financial systems.

Bitcoin is often derided as volatile, but a new report suggests there is a method to the madness.

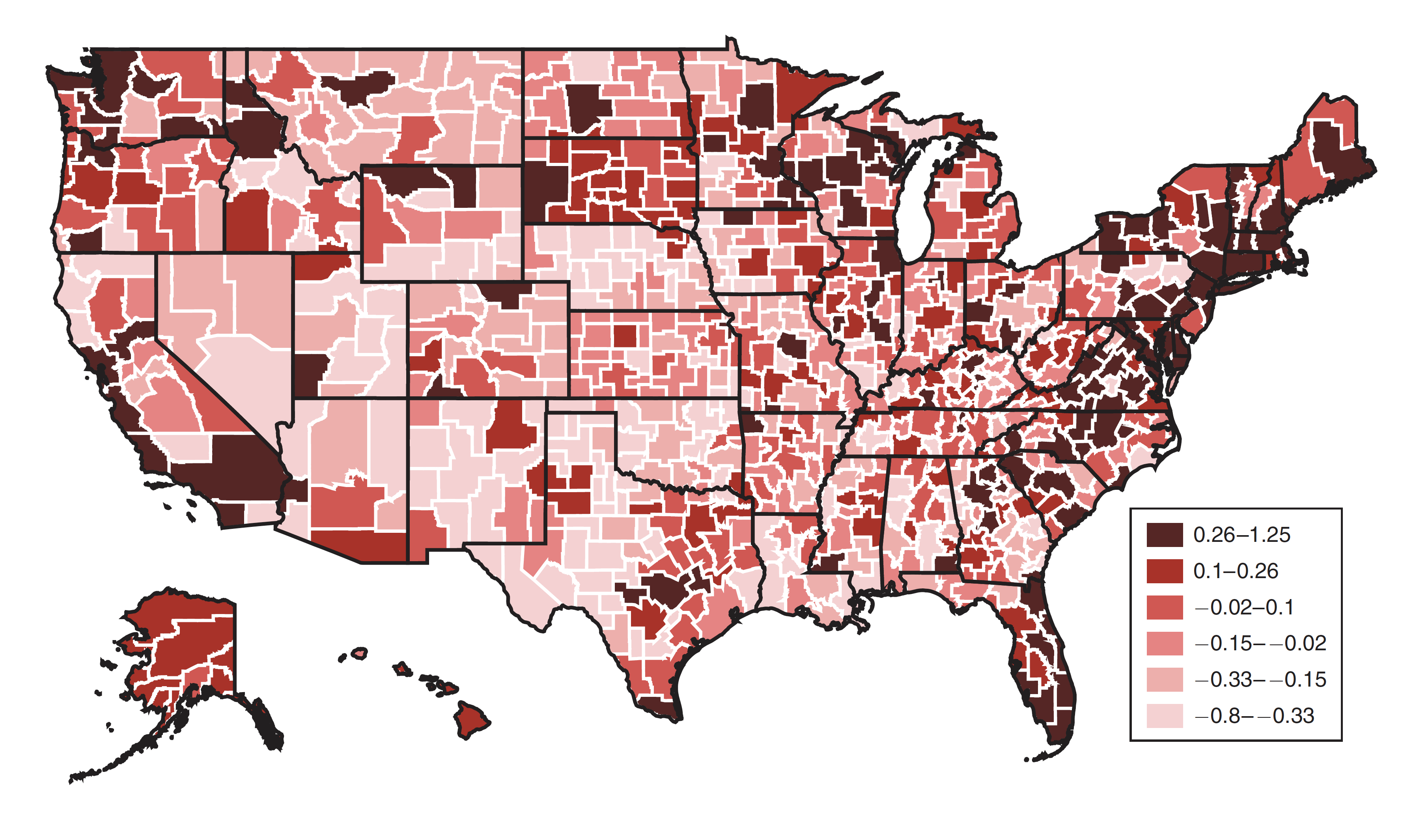

Longevity gets a new motto: location, location, location.

Bitcoin’s creator owns five percent of the entire Bitcoin supply, meaning that he has a larger percent of Bitcoin than the U.S. has of gold.

The Seychelles magpie-robin is up for sale – yes, for sale – as a digital nature collectible.

By slowing down aging, we could reap trillions of dollars in economic benefits.

Most schools use a semester system, but a new study suggests that they should switch to quarters.

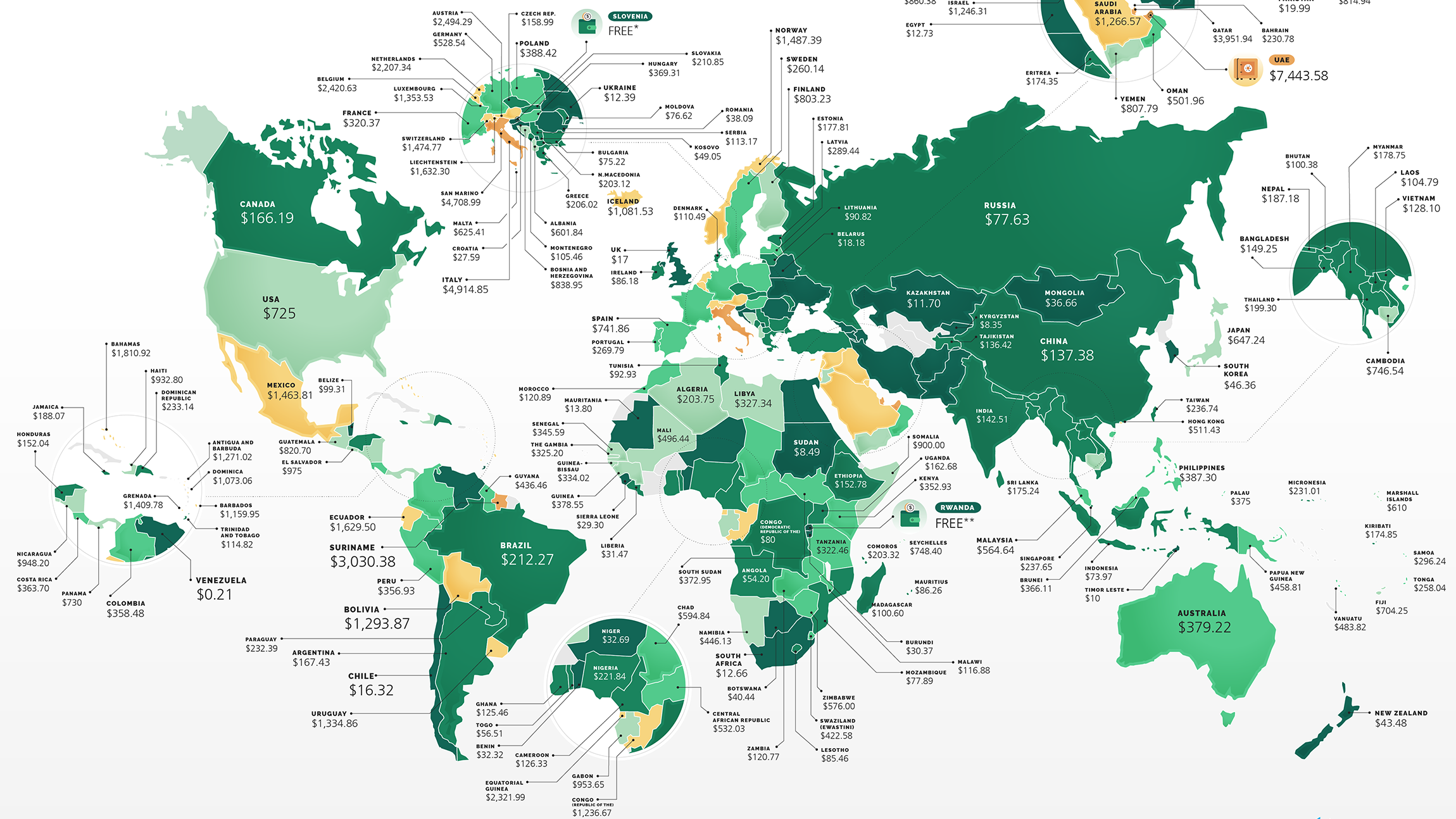

UAE is the world’s most expensive country to start a business, but it’s free in Rwanda.

As air pollution increases, so does violent crime.

A cartogram makes it easy to compare regional and national GDPs at a glance.

Information economics suggests that “no news” means somebody is hiding something. But people are bad at noticing that.

Say hello to your new colleague, the Workplace Environment Architect.

Science journals may be lowering their standards to publish studies with eye-grabbing — but probably incorrect — results.

As bad as this sounds, a new essay suggests that we live in a surprisingly egalitarian age.

A new study explores how investors’ behavior is affected by participating in online communities, like Reddit’s WallStreetBets.

A new study suggests that private prisons hold prisoners for a longer period of time, wasting the cost savings that private prisons are supposed to provide over public ones.

The design of a classic video game yields insights on how to address global poverty.

The world’s 10 most affected countries are spending up to 59% of their GDP on the effects of violence.

The neoliberal call for more ‘choice’, seems hard to resist.

What’s to blame for the recent uptick in containership accidents?

Understand everything that goes behind payroll, debits, credits, and more with this 25-hour course collection.

The British economic anthropologist Jason Hickel proposes “degrowth” in the face of recession.

Most people seem to enjoy liberalism and its spin offs, but what is it exactly? Where did the idea come from?

The more you donate, the greater your chances.

This real estate training covers property management, construction cost estimation, social housing, and much more.

Inequality in wealth, gender, and race grew to unprecedented levels across the world, according to OxFam report.