Why We Love to Swear So G*dd#mned Much

Whether you use “bad” language or not, it’s clear that this is a family of words with unique power. It’s not completely clear why. We’re not talking about slurs, foul language intended to denigrate someone or a group of people. We know where that power comes from — hate — and why it’s potent: It hurts people. The profanity we’re talking about is defined by Google thusly:

We know that there’s no such thing as a truly bad word — there’s no real-world phrase to make someone drop dead like Harry Potter’savada kedavra (and if so, whoops). So what’s so bad about profanity? Nothing really. It’s just that these are words that make some people uncomfortable, and so they should only be used with care, and an awareness of one’s audience. But, boy, do they pack a punch.

It could be argued that only its overuse has the ability to strip away profanity’s shock value. A comedian who’s every other word is a swear risks diluting its impact. And many feel that curses are simply a path of least resistance for vocabulary-challenged people trying to make a point.

Author Michael Adams, in his book In Praise of Profanity, asserts that naughty language is a good thing, not least because it brings people together. He says, “Bad words are unexpectedly useful in fostering human relations because they carry risk….We like to get away with things and sometimes we do so with like-minded people.”

Adams believes that a dirty word’s forbidden nature is why it’s so electric: it’s the thrill of the taboo. To him, this accounts for profanity’s importance in writing, whether that’s literature like Catcher in the Rye, TV or film like The Sopranos or Pulp Fiction, music (choose your favorite potty-mouth artist), or even a successful children’s book, like Go the Fuck to Sleep. It’s this off-limits nature that imbues it with an element of surprise to make a joke funnier, or an angry statement more powerful.

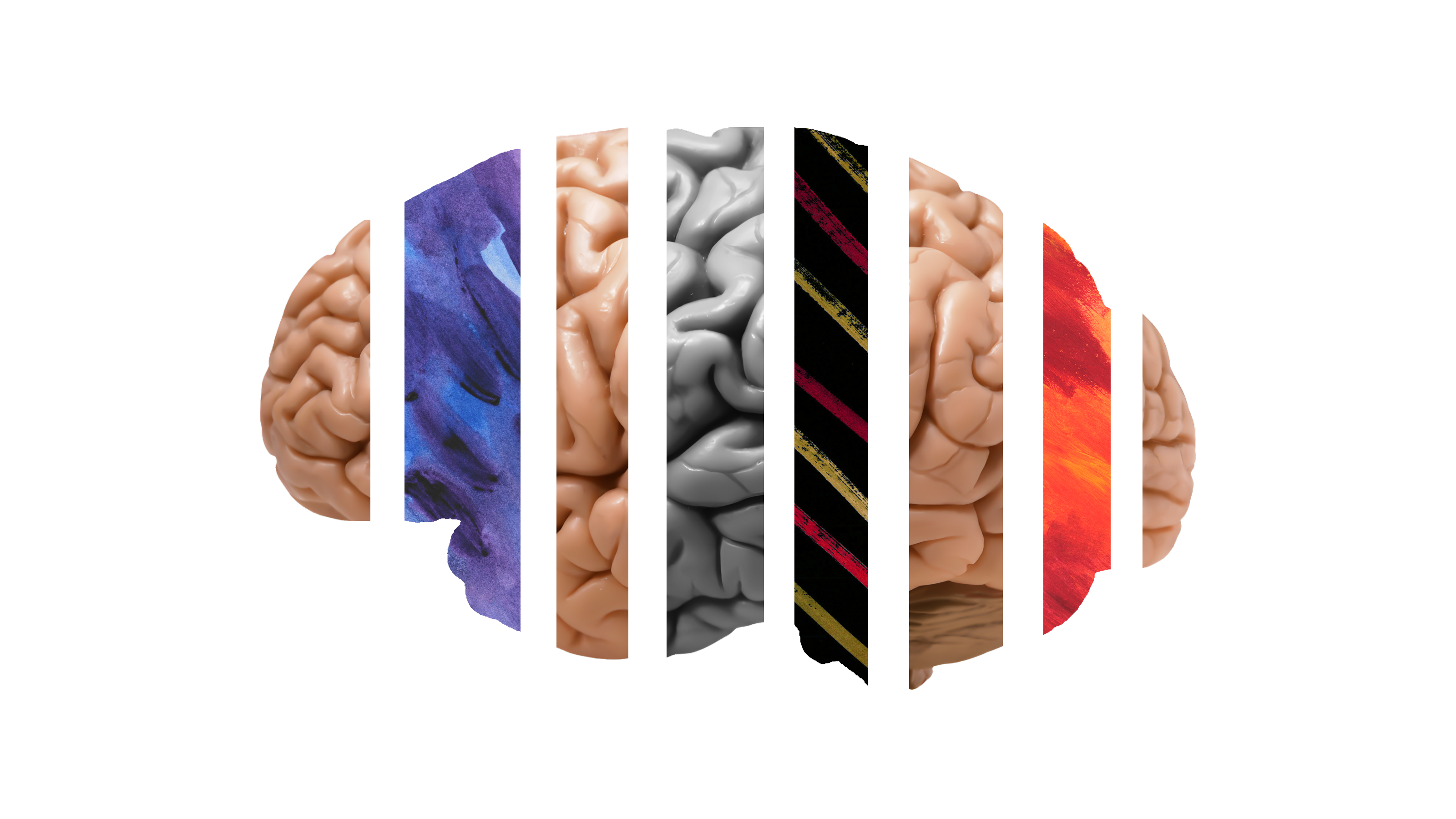

Linguist Benjamin Bergen of the Cognitive Science Department at UC San Diego has a new book, What the F: What Swearing Reveals About Our Language, Our Brains, and Ourselves, that makes the case there’s something neurological behind the power and pleasures of profanity. He presents evidence that swear words come from, and please, a very particular region of the brain separate from the areas that govern normal speech.

Damage to those two regions in the brain’s left hemisphere — Broca’s area, which produces words, and Wernicke’s area, which is your built-in user dictionary — have been seen to result in aphasics who can’t talk normally anymore, but they sure can spontaneously swear, like you might after smashing your finger with a hammer. (Bergen is particularly fond of a priest who suffered a stroke in 1843 that left him with a vocabulary only a sailor could love.) So where are all these choice expressions coming from?

It appears now that it comes from the right hemisphere of the brain, in the basal ganglia. This insight comes from the case of a different priest who lost his ability to swear — what’s with priests and swearing? — when his basal ganglia was damaged. What’s especially interesting about this finding is that this is an ancient, primitive area of the brain that has to do with emotional responses, as well as motor control. Sufferers of Tourette’s syndrome, that involves involuntarily shouted profanities, also have damaged basal ganglia.

This hard-wiring of profanity to the brain’s emotion center is fascinating. Maybe the taboo thrill of profanity is just icing on the cake. Maybe profanity is just the language of our emotions.

Most people who enjoy words and value an expansive vocabulary have an appreciation for well-used profanity, and Bergen’s “book-length love letter to profanity” isn’t all science. In it, you can learn, among other things, that the first words out of all Samoan babies’ mouths are apparently “eat &%$!,” and that the Japanese don’t have any swear words at all, forcing their Tourette’s sufferers to shout childhood words for genitalia.

So whether it’s culture or biology, profanity is here to stay. To which one can only respond, of course, “F#^k yeah.”