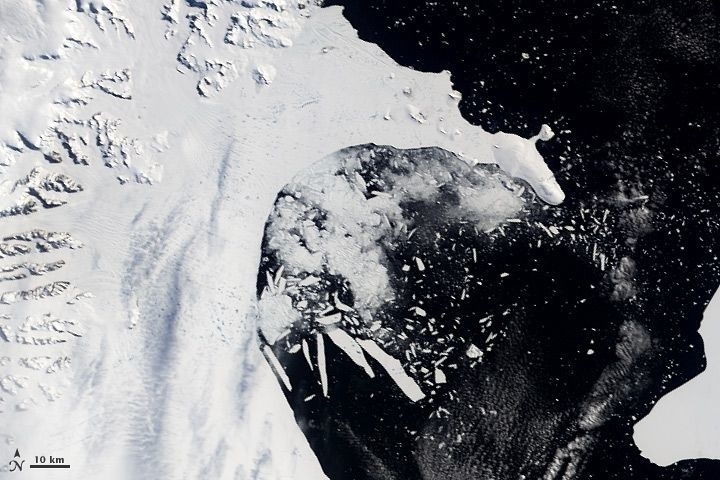

An Alaskan landslide is imminent and so is its tsunami, say geologists

Image source: Christian Zimmerman/USGS/Big Think

- A remote area visited by tourists and cruises, and home to fishing villages, is about to be visited by a devastating tsunami.

- A wall of rock exposed by a receding glacier is about crash into the waters below.

- Glaciers hold such areas together — and when they’re gone, bad stuff can be left behind.

The Barry Glacier gives its name to Alaska’s Barry Arm Fjord, and a new open letter forecasts trouble ahead.

Thanks to global warming, the glacier has been retreating, so far removing two-thirds of its support for a steep mile-long slope, or scarp, containing perhaps 500 million cubic meters of material. (Think the Hoover Dam times several hundred.) The slope has been moving slowly since 1957, but scientists say it’s become an avalanche waiting to happen, maybe within the next year, and likely within 20. When it does come crashing down into the fjord, it could set in motion a frightening tsunami overwhelming the fjord’s normally peaceful waters .

“It could happen anytime, but the risk just goes way up as this glacier recedes,” says hydrologist Anna Liljedahl of Woods Hole, one of the signatories to the letter.

Camping on the fjord’s Black Sand BeachImage source: Matt Zimmerman

The Barry Arm Fjord is a stretch of water between the Harriman Fjord and the Port Wills Fjord, located at the northwest corner of the well-known Prince William Sound. It’s a beautiful area, home to a few hundred people supporting the local fishing industry, and it’s also a popular destination for tourists — its Black Sand Beach is one of Alaska’s most scenic — and cruise ships.

Image source: whrc.org

There have been at least two similar events in the state’s recent history, though not on such a massive scale. On July 9, 1958, an earthquake nearby caused 40 million cubic yards of rock to suddenly slide 2,000 feet down into Lituya Bay, producing a tsunami whose peak waves reportedly reached 1,720 feet in height. By the time the wall of water reached the mouth of the bay, it was still 75 feet high. At Taan Fjord in 2015, a landslide caused a tsunami that crested at 600 feet. Both of these events thankfully occurred in sparsely populated areas, so few fatalities occurred.

The Barry Arm event will be larger than either of these by far.

“This is an enormous slope — the mass that could fail weighs over a billion tonnes,” said geologist Dave Petley, speaking to Earther. “The internal structure of that rock mass, which will determine whether it collapses, is very complex. At the moment we don’t know enough about it to be able to forecast its future behavior.”

Outside of Alaska, on the west coast of Greenland, a landslide-produced tsunami towered 300 feet high, obliterating a fishing village in its path.

Moving slowly at first…Image source: whrc.org

“The effects would be especially severe near where the landslide enters the water at the head of Barry Arm. Additionally, areas of shallow water, or low-lying land near the shore, would be in danger even further from the source. A minor failure may not produce significant impacts beyond the inner parts of the fiord, while a complete failure could be destructive throughout Barry Arm, Harriman Fiord, and parts of Port Wells. Our initial results show complex impacts further from the landslide than Barry Arm, with over 30 foot waves in some distant bays, including Whittier.”

The discovery of the impeding landslide began with an observation by artist Valisa Higman, who was vacationing in the area and sent her geologist brother some photos of worrying fractures she noticed in the slope, taken while she was on a boat cruising the fjord. Her brother, Hig Higman of Ground Truth, an organization in Seldovia, Alaska, confirmed his sister’s hunch via available satellite imagery and, digging deeper, found that between 2009 and 2015 the slope had moved 600 feet downhill, leaving a prominent scar.

Ohio State’s Chunli Dai unearthed a connection between the movement and the receding of the Barry Glacier. Comparison of the Barry Arm slope with other similar areas, combined with computer modeling of the possible resulting tsunamis, led to the publication of the group’s letter.

While the full group of signatories from 14 organizations and institutions has only been working on the situation for a month, the implications were immediately clear. The signers include experts from Ohio State University, the University of Southern California, and the Anchorage and Fairbanks campuses of the University of Alaska.

Once informed of the open letter’s contents, the Alaska’s Department of Natural Resources immediately released a warning that “an increasingly likely landslide could generate a wave with devastating effects on fishermen and recreationalists.”

Image source: whrc.org

The obvious question is what can be done to prepare for the landslide and tsunami? For one thing, there’s more to understand about the upcoming event, and the researchers lay out their plan in the letter:

“To inform and refine hazard mitigation efforts, we would like to pursue several lines of investigation: Detect changes in the slope that might forewarn of a landslide, better understand what could trigger a landslide, and refine tsunami model projections. By mapping the landslide and nearby terrain, both above and below sea level, we can more accurately determine the basic physical dimensions of the landslide. This can be paired with GPS and seismic measurements made over time to see how the slope responds to changes in the glacier and to events like rainstorms and earthquakes. Field and satellite data can support near-real time hazard monitoring, while computer models of landslide and tsunami scenarios can help identify specific places that are most at risk.”

In the letter, the authors reached out to those living in and visiting the area, asking, “What specific questions are most important to you?” and “What could be done to reduce the danger to people who want to visit or work in Barry Arm?” They also invited locals to let them know about any changes, including even small rock-falls and landslides.