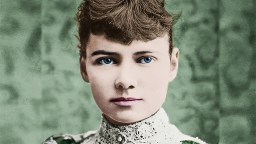

Elizabeth Kenny’s Treatment Went against the Medical Establishment

Big Think is proud to partner with the 92Y in bringing you this series on female genius as part of its 7 Days of Genius Festival.

Elizabeth Kenny was a woman celebrated in her own time. She beat Eleanor Roosevelt as the most admired woman in the world in a 1951 Gallup Poll. After her death the next year, Eleanor Roosevelt would continue to hold that distinction for 10 years until Jacqueline Kennedy entered the spotlight. Kenny was known for her contributions to treating polio, which is why few know her name today.

There aren’t many alive that remember polio’s paralyzing effects as memory of the disease dies with its last survivors; it’s up to history to remember and honor the people who helped treat the disease.

Kenny went against conventional science for treating polio. The orthodox methods for these cases of paralysis from polio was to keep the affected extremities in splints. She believed a patient should have an active role in their recovery.

When she first encountered the disease in 1911, she didn’t know what to make of it. Children arrived at her outpost in the Australian bush with fever and body aches. The disease would eventually take its toll, paralyzing some children.

Kenny would have to telegram the nearest doctor for assistance, as she knew of no treatment for this strange new disease.

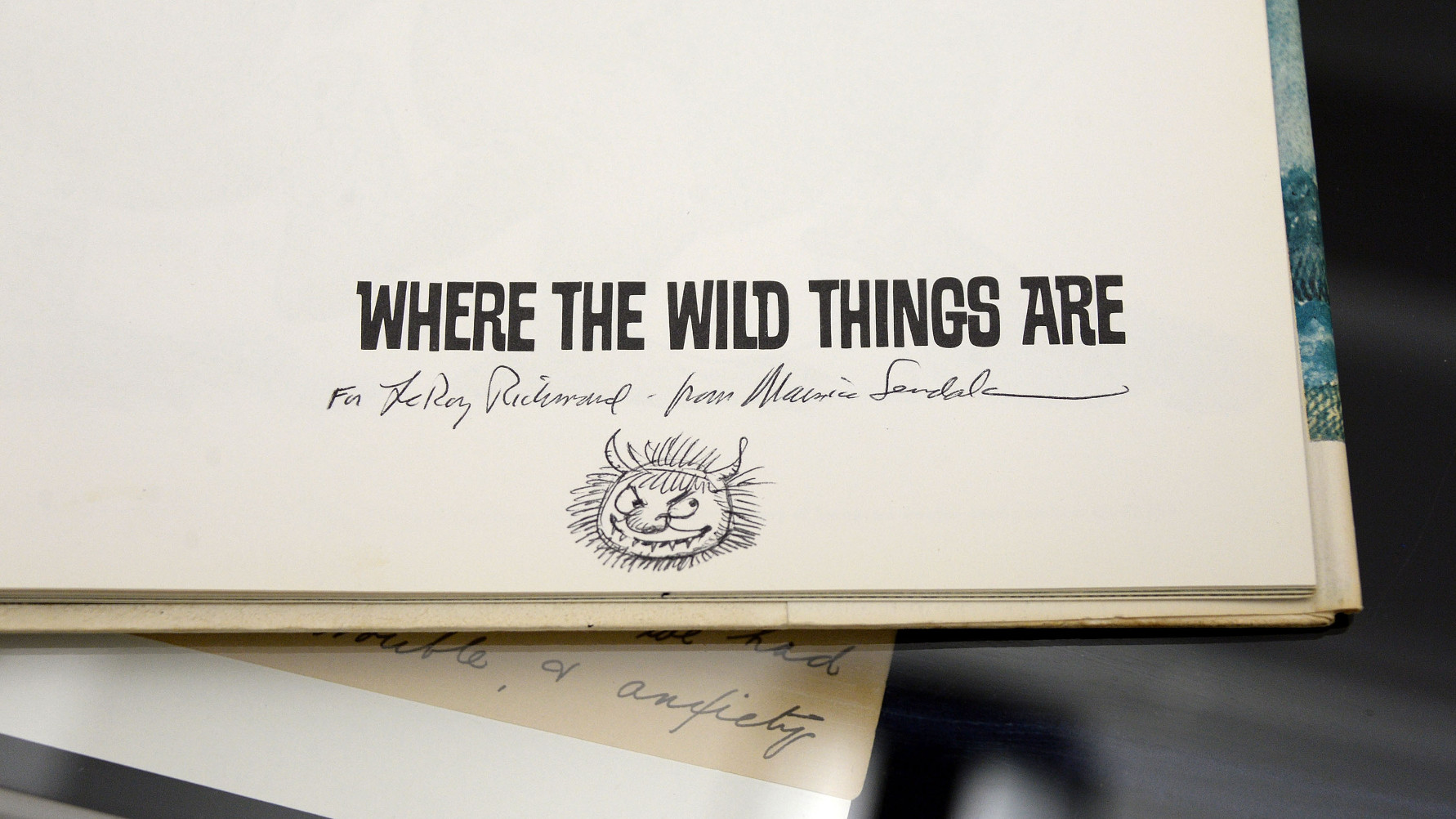

“In my anxious suspense, the reply to my telegram was anything but heartening. It read, ‘Infantile paralysis. No known treatment. Do the best you can with the symptoms presenting themselves.’ It was signed by Dr. Aeneas McDonnell,” Kenny later wrote in her autobiography And They Shall Walk.

However, her ignorance of the disease may have proved to be her greatest strength in deducing a strategy to help the ailing children who came to her outpost.

“I knew the relaxing power of heat. I filled a frying pan with salt, placed it over the fire, then poured it into a bag and applied it to the leg that was giving the most pain. After an anxious wait, I saw that no relief followed the application. I then prepared a linseed meal poultice, but the weight of this seemed only to increase the pain.

“At last I tore a blanket made from soft Australian wool into suitable strips and wrung them out of boiling water. These I wrapped gently about the poor, tortured muscles. The whimpering of the child ceased almost immediately, and after a few more applications her eyes closed slowly and she fell asleep,” she wrote.

Her world would continue to expand when she entered World War I as a nurse for the British army on “Dark Ships.” These vessels would make the journey from Australia to England with all lights off, transporting goods and soldiers from one edge of the Earth to the other. It was here she earned the rank of lieutenant and the title of “Sister.”

In the 1920s and ’30s, around the world, polio was spreading. Through her knowledge of the musculoskeletal system, she would go on to develop a method of physical therapy that discarded the braces and calipers prescribed by most doctors of the time and encouraged active movements. She believed after the paralysis, the muscles had to be re-educated through passive exercises.

This treatment flew in the face of conventional treatment, which said the affected limbs must be protected by remaining immobilized. Kenny was a nurse and a woman going against the wisdom of doctors and men; she irked much of the medical community (most notably the American Medical Association). Kenny was outspoken, however, and her tendency to embellish her understanding of the disease would often be used to discredit her work. But the evidence of her work, which lived on in the success stories of her patients, proved her methods were valid.

Attention to her patients helped her succeed in finding a treatment. In an era where randomized, controlled clinical trials were the basis for scientific evidence, she showed individual bedside medicine could be a basis for discovery — a watchful eye and an empathetic ear.

***

Natalie has been writing professionally for about 6 years. After graduating from Ithaca College with a degree in Feature Writing, she snagged a job at PCMag.com where she had the opportunity to review all the latest consumer gadgets. Since then she has become a writer for hire, freelancing for various websites. In her spare time, you may find her riding her motorcycle, reading YA novels, hiking, or playing video games. Follow her on Twitter: @nat_schumaker