In the Baltics, 85 millimeters separate East from West

- The European Union is funding a new high-speed train line to link the Baltic capitals with the rest of Europe.

- Rail Baltica aims to enable the region to break free from the Soviet rail system — and Moscow’s influence.

- Considering its strategic importance, the project is not doing so well: It’s over budget, and there’s no end date for its completion.

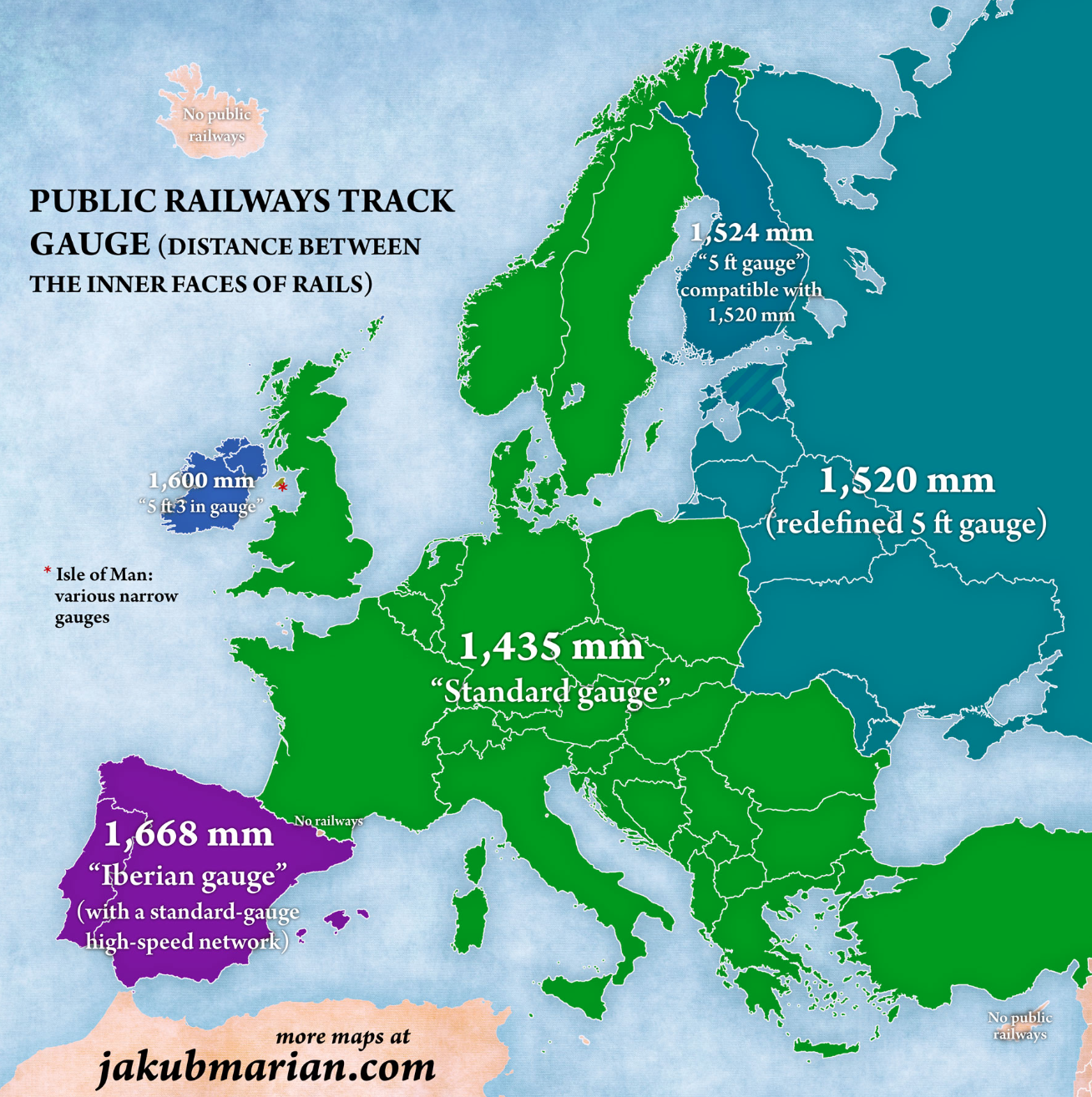

In the Baltics, the difference between East and West — between the past and the future — can be measured in millimeters: 85, to be exact. (Or, if you prefer, 3.35 inches.)

That tiny distance is the difference between the track gauges of the old Soviet railways (1,520 mm, just under 5 ft), which are still used by all former republics of the USSR, and standard gauge (1,435 mm; 4.7 ft) used almost everywhere else in Europe.

Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia were the first republics to declare their independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, and in 2004 joined both the European Union and NATO. But their railway network is still stuck in Soviet times.

Even today, there is no direct rail link between the Baltics and the rest of the EU. Passengers and cargo both need to switch trains at the Polish border. That delay was of course the point of the Soviets’ singular system: It was designed to slow down any invasion of the USSR coming from the West.

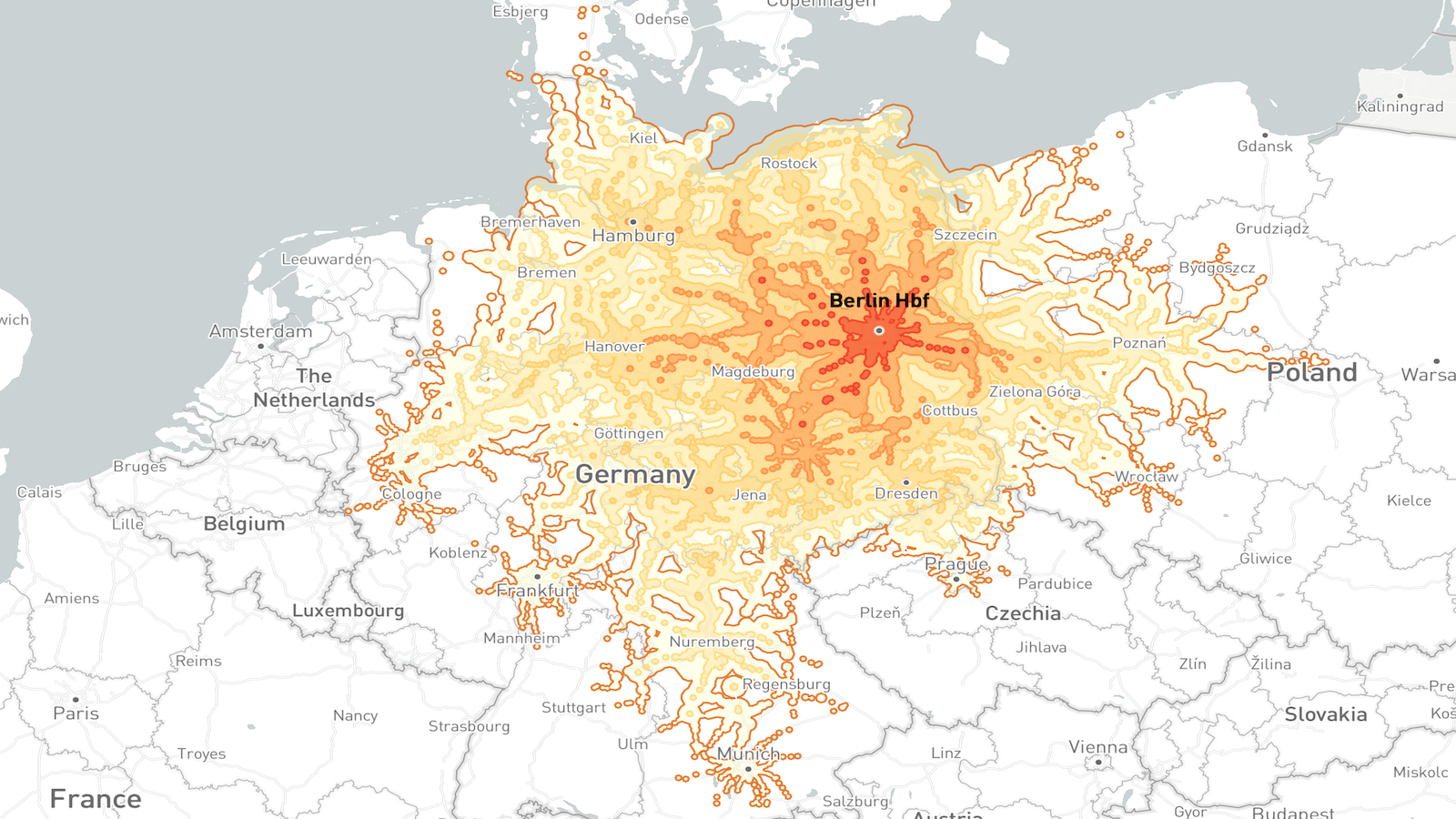

Enter Rail Baltica, a project currently in the works that will reverse the transport isolation of the Baltic states by seamlessly linking all three to the EU’s rail network, via high-speed, standard-gauge rail.

It is the largest single infrastructure project in the Baltics this century — and possibly any century. The high-speed line will provide more than economic benefits: It will allow the region to reduce its economic ties with the former Soviet space by reorienting itself towards the rest of Europe — a move with both practical and symbolic significance.

Following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, there’s also a strategic dimension: Rail Baltica will permit rapid reinforcements of the 10,000 NATO troops currently stationed in the region, should Moscow turn its acquisitive attention here.

The precursor and inspiration for Rail Baltica was a curious event that occurred on August 23, 1989, when up to 2 million people linked hands across Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia — then still part of the Soviet Union — to form the longest human chain in history.

Spanning 690 km (430 miles), the so-called “Baltic Way” was a stunning display of the desire of the three Baltic states to break free from Moscow’s control. Seven months later, Lithuania was the first Soviet republic to effectively declare its independence, ushering in the end of the USSR.

More than three decades after political independence, Rail Baltica will help the region to finally uncouple from Russia’s transport network, and integrate economically with the European Union.

Some specifications of the line, now under construction:

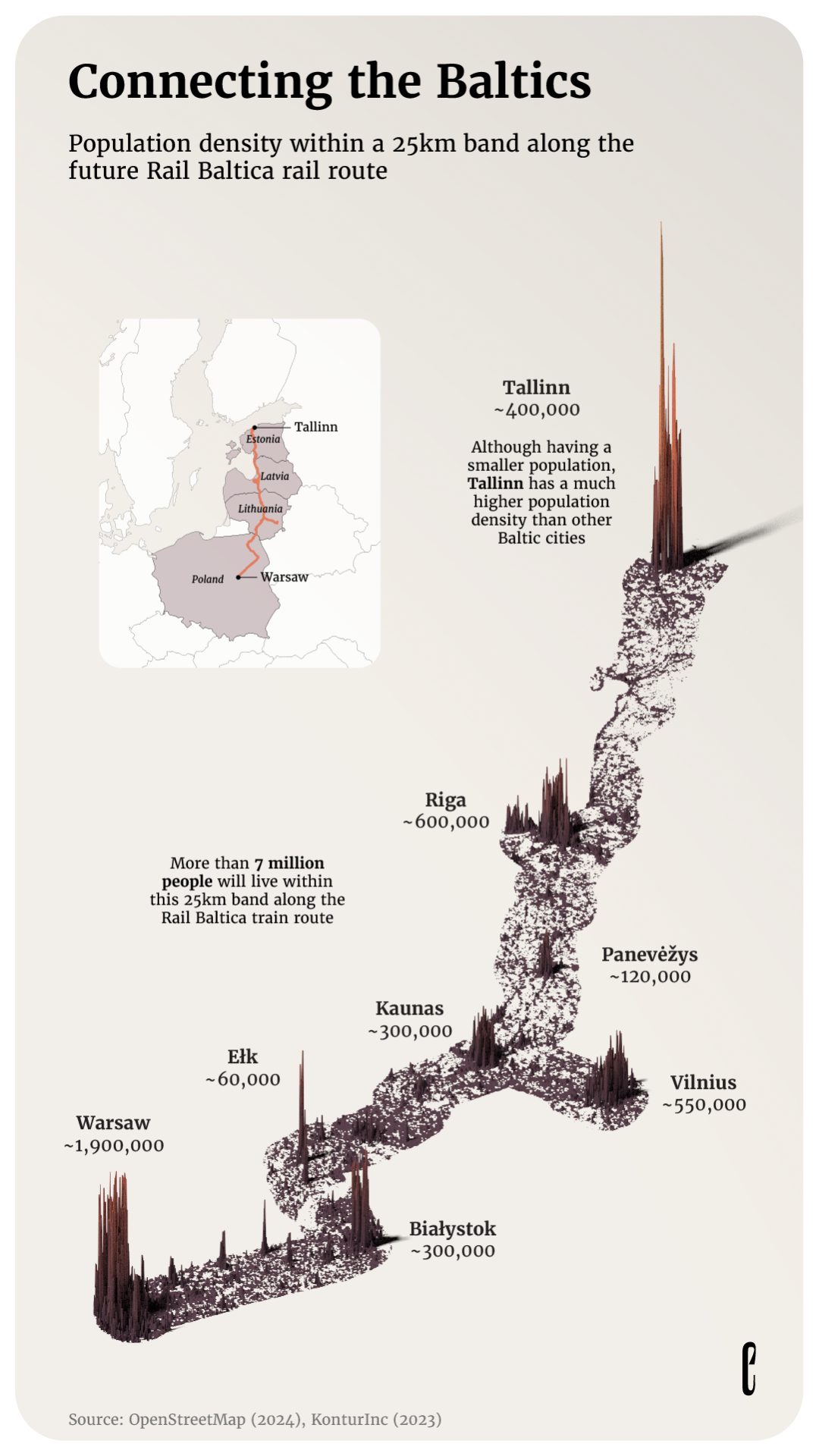

- The standard-gauge track will be 870 km (540 mi) long in the Baltic states, connecting the Estonian capital Tallinn with the Latvian capital Riga, and with Kaunas, Lithuania’s second-largest city. Branch lines will connect to Riga International Airport and Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital. The line will continue seamlessly to Warsaw, the capital of Poland, for a total length of 950 km (590 mi).

- Rail Baltica will offer at least one international passenger train every two hours, or a total of eight trains in either direction every day. These trains will travel at 234 km/h (145 mph) in the Baltics, cutting rail travel time between Tallinn and Vilnius from 12 hours to less than four. The Polish part of the line will be upgraded to accommodate passenger trains at 200 km/h (124 mph).

- The line will be able to accommodate freight trains with a maximum length of 1,050 m (3,440 ft), traveling at a top speed of 120 km/h (75 mph). This will help reduce freight traffic by truck in the region by up to 40%, as well as lower the cost of shipping itself.

- As is typical for megaprojects, the estimated total cost for Rail Baltica has ballooned, from €5.8 billion in 2017 to €24 billion today. Covid and the Ukraine war have been blamed for driving up the cost of materials. The EU has paid 85% of the cost so far. The remainder is nevertheless a heavy burden on the Baltic states, considering the small size of their populations and economies.

The project is being tackled in two phases. The first, consisting of a single track connecting the most important stations, will cost €15 billion and is slated for completion by 2030, but with services already starting on some sections by 2028. The second, completing the whole project, currently has no end date.

High-speed train lines are always much more expensive than originally budgeted, and take much more time to complete. This increases the risk that the scope of the project is reduced, as happened to the UK’s HS2 project, now only going from London to Birmingham instead of all the way to Manchester.

Will the same happen to Rail Baltica? Probably not, as the EU considers it a priority project that will complete the so-called North Sea-Baltic Corridor, itself part of TEN-T, a blueprint for trans-European transport corridors. Those should serve as catalysts for economic development, and some forecasts do point to major benefits:

- The project itself will generate 13,000 extra jobs directly connected with construction, and an additional 24,000 jobs indirectly.

- Once completed, Rail Baltica will save billions in passenger and freight travel costs, millions of passenger hours, and hundreds of lives not lost in road traffic.

- Total measurable socio-economic benefits have been estimated at €16.2 billion. Unmeasurable benefits include better opportunities for tourism, exports, and inward investments.

And those benefits don’t even account for the proposed northern extension of Rail Baltica to Helsinki, via a rail tunnel below the Gulf of Finland.

Dubbed the Talsinki Tunnel for the two capitals it would connect, that tunnel would be at least 80 km (50 mi) long, making it 40% longer than the Gotthard Base Tunnel, currently the world’s longest railway tunnel. However, at the moment, there are no concrete plans to start digging a hole from Estonia to Finland, or vice versa.

Initial cost estimates for the tunnel range from €9 to €13 billion. It will probably be some time before the EU and the Baltic states feel ready to commit to such a high-cost project, especially as there are plenty of other pressing matters waiting for a solution — for example, the regional power grid, which is still integrated with Russia.

But not for long: In February 2025, the Baltic states will decouple from the Russian grid, and integrate their power networks with the European grid. It’s yet another example of how, from a Baltic perspective, the Ukraine war has turned an annoying hangover from Soviet times into an existential threat.

The main map was first published by The European Correspondent, a network of journalists who tell data-driven stories that help you understand the continent. They have compiled 33 visualizations into a book that provides as many insights into various aspects of life across Europe. More on that here.

Strange Maps #1262

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on X and Facebook.