An interactive map with bizarre poems about England

- Your standard map is pretty prosaic. What happens if you add poems?

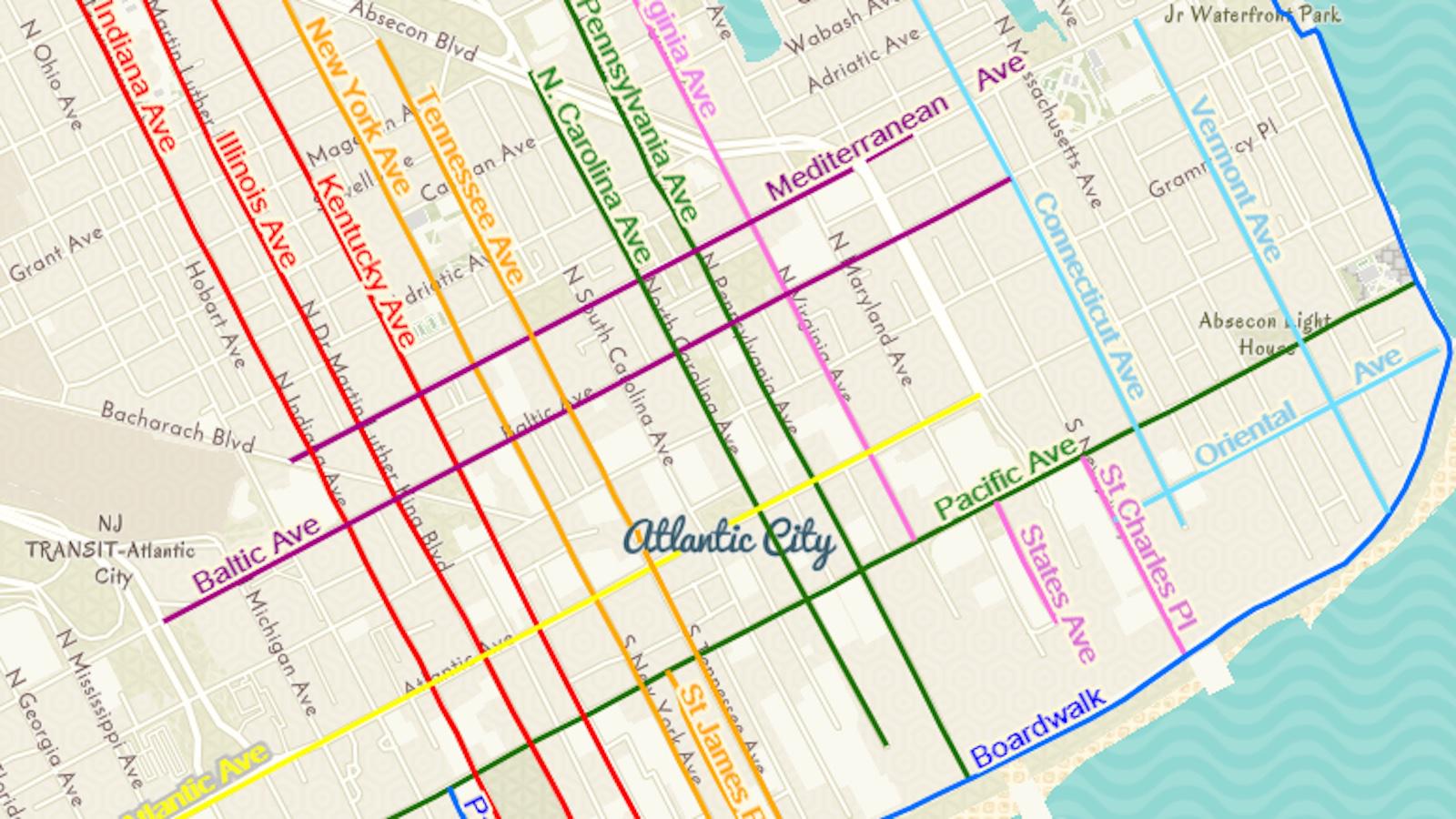

- Places of Poetry is an interactive map of the UK that does just that.

- Be forewarned: Clicking to the next poem becomes an addictive joy.

Are some places inherently poetic while others are not? Or has the right poem just not yet been written about the dumpster area behind your local supermarket? It’s a question that Places of Poetry could help illuminate. This interactive map of the United Kingdom acts as an interface between various places in the British Isles, and the poems that have been written about them.

A unique poetic resonance

The page’s title is a reversal of the well-worn phrase “poetry of place,” which is the idea that certain locales have a unique poetic resonance. A classic example is that of the picturesque wilderness of northern England’s Lake District, which drew in William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and others, known collectively as the “Lake Poets.”

Wordsworth and Coleridge feature on this map, but it is mainly populated by lesser-known and more contemporary wordsmiths. Places of Poetry was in fact a project in 2019 that invited the British public to pin their own poems of place to the map, or their favorite ones by others (as long as they were out of copyright).

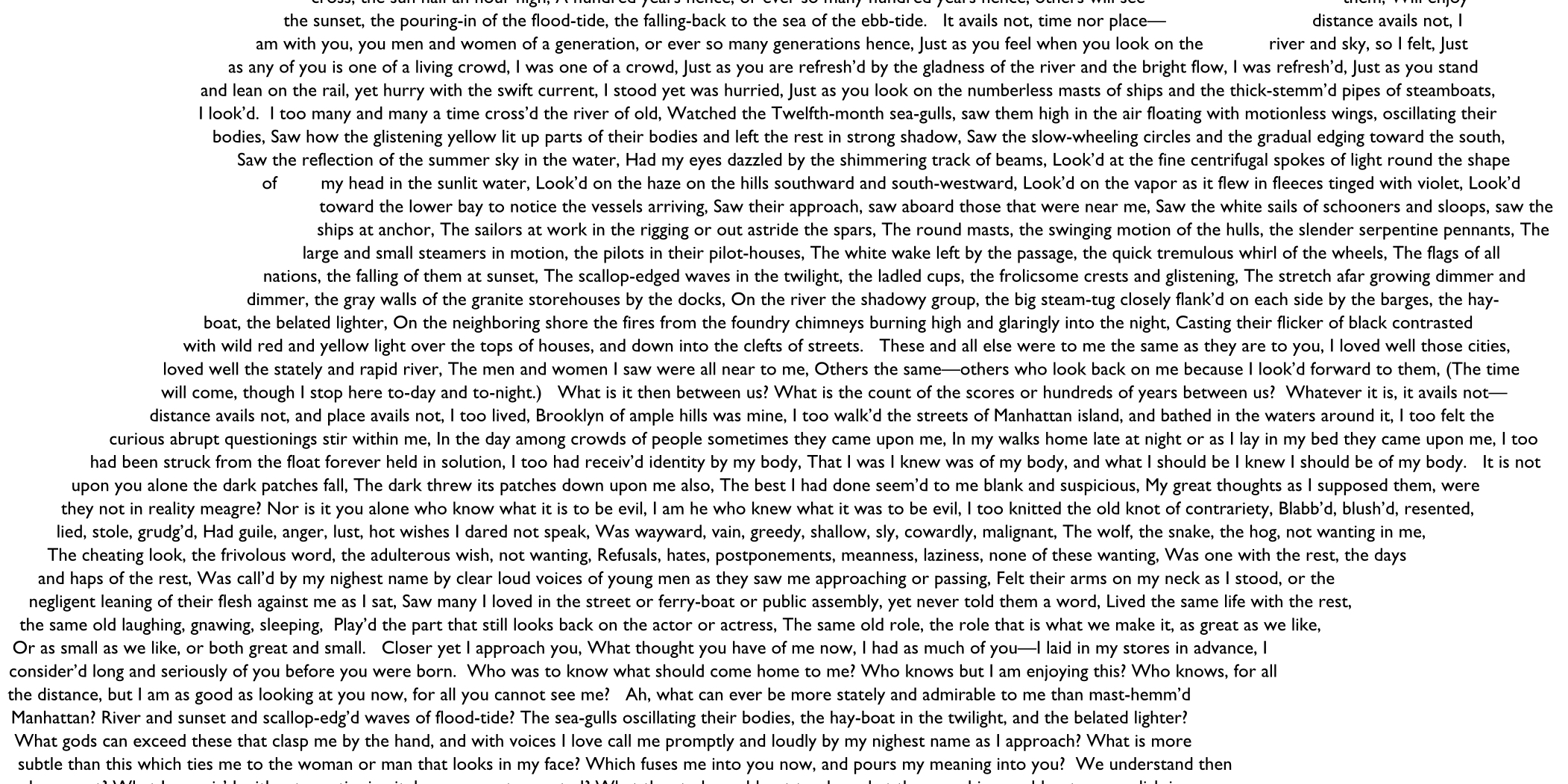

One such poem is Coleridge’s “Sonnet: to the River Otter,” which begins:

Dear native brook! wild streamlet of the West!

How many various-fated years have passed,

What happy and what mournful hours, since last

I skimmed the smooth thin stone along thy breast

But poems of place don’t all need to be poems about nature. It’s not just bee-loud glades and lapping lake water (as in Yeats’ famous poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” based on Lough Gill in Ireland, which is beyond the scope of this map). There’s plenty of poetic resonance in urban settings too.

A quantitative theory of poetry

In fact, at first glance and furthest zoom level, London is the most poetic place in the United Kingdom, with more than 950 mentions. Or is it? A purely quantitative theory of poetry is probably not a good idea. A purely quantitative theory of poets, however, does offer some context: London simply is the biggest city in the UK. Where lots of people live, you’ll find more than a few poets.

How many? Is there perhaps a consistent ratio of poets to the general population? It’s hard to say. Hilariously hard, in fact. According to stats by Zippia, there are “over 148 poets in the United States.” While technically not wrong, that is probably quite a bit off the mark. Those stats also specify that 80% of U.S. poets are white, 63% are women, and the average age is 42 years old. And 16% are LGBT, which is a higher share than PR assistants, but a lower one than broadcast meteorologists. But we’re getting off track.

Let’s return to the map, according to which there are/were at least several hundred poets in London. What do their poems tell us about their lives and the places they lived? Have they produced immortal lines that will draw tourists by the thousands?

John Davison’s “Here’s to you in Zone Two” starts off quite intriguingly:

Out there in Zone Two, to the west of Deptford Creek,

Lives a tribe of wind-blown fathers — it’s a quite distinctive clique;

They walked the college corridors when students all gained grants,

And remember when Deep Purple meant a good excuse to dance.

He goes on to describe a particular type of middle-class man who dresses in corduroy, enjoys wrought-iron balconies, and has daughters with classical degrees. Well, now we know where to find them: west of Deptford Creek.

Circumstances are a lot more precarious in Lydia Kennaway’s “Bedsit: Earl’s Court Road, 1977,” in which she invites a man into her cheap accommodation with “(m)eter boxes, army green, like relics from the Blitz, hungry for clunky coins thick as two nickels put together.”

Morning.

The gas has run out.

The electricity has run out.

I slide out of the crackling sheets. He stirs

then watches as I open fibreglass curtains

to windows weeping with condensation.

I peer down at blurred umbrellas and red buses.

‘Lovely’ he says.

With poems penned in prisons and palaces, about desire and disgust, and anywhere and anything in between, a picture emerges from London that is not found in guidebooks, with the inner life of its inhabitants and visitors as the signposts of an otherwise invisible landscape.

UFO eyewitness report

It’s an exercise that is repeated across the country, adding an unexpected dimension to the map of the United Kingdom — although not all poems are equally profound. Sometimes, as in “UFOs” by JP, pinned to the northern English town of Ashington, they serve merely as eyewitness reports:

This is where we saw them

Three balls in the sky

They hovered for a minute

We thought that we might die

The addictive joy of this map is that you never know what you’re going to get. Here’s part of a poem by Angie Holden about “Winsford,” an otherwise unremarkable town in the middle of Cheshire:

Afternoon tea:

scones and jam and clotted cream.

He turns over the paper napkin

and draws a teapot.

Spout to the left — Chester, he says —

handle to the right:

Macclesfield, Congleton.

A knobbed lid on the top:

Warrington.

He marks the centre with a single cross.

That’s Winsford. Where I come from.

Haiku-like brevity

It’s a map in a poem, in a poem on a map! Or you could come across a poem of haiku-like brevity and clarity, as in “Old way” by Sarah Rawlins, set in the woods overlooking Lyme Regis and the English Channel:

Old way

Scots Pine,

pitch perfect spine

black against azure sea.

In closing — because by now you get the idea — a love letter of sorts: “I want to live forever in Wales,” by Abigail Elizabeth Rowland:

where dogs on shining beaches chase after

yellow tennis balls and always bring them tail-wagging back

where the tender lapping ocean ripples through rainbows

before it slips into the arms of the sky

where windmills and sea-gulls compete to discover whose

glittering wings in their dipping and soaring

shine best in the late low sunshine

I want to live forever in Wales.

The map on Place of Poetry used as background for the pins is an adaptation of maps used for the Poly-Olbion (1612), an epic poem about the character and identity of England and Wales, county by county.

Strange Maps #1184

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.