Let George Orwell guide you through 1920s Paris

- In 1928, George Orwell went to Paris to learn French, live cheaply, and write novels.

- Most of his stay was spent in abject poverty, actual hunger, and hunting for menial work.

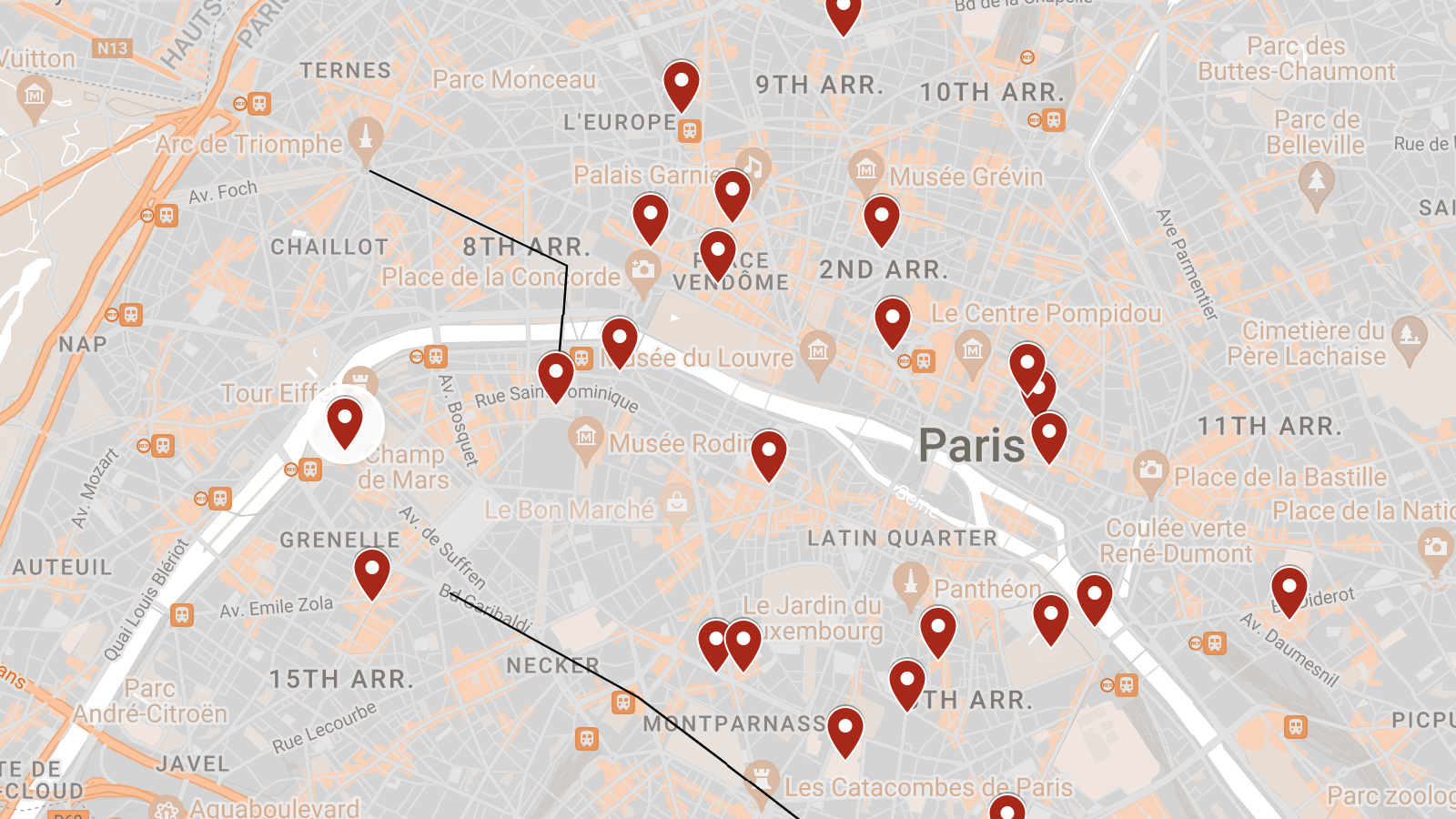

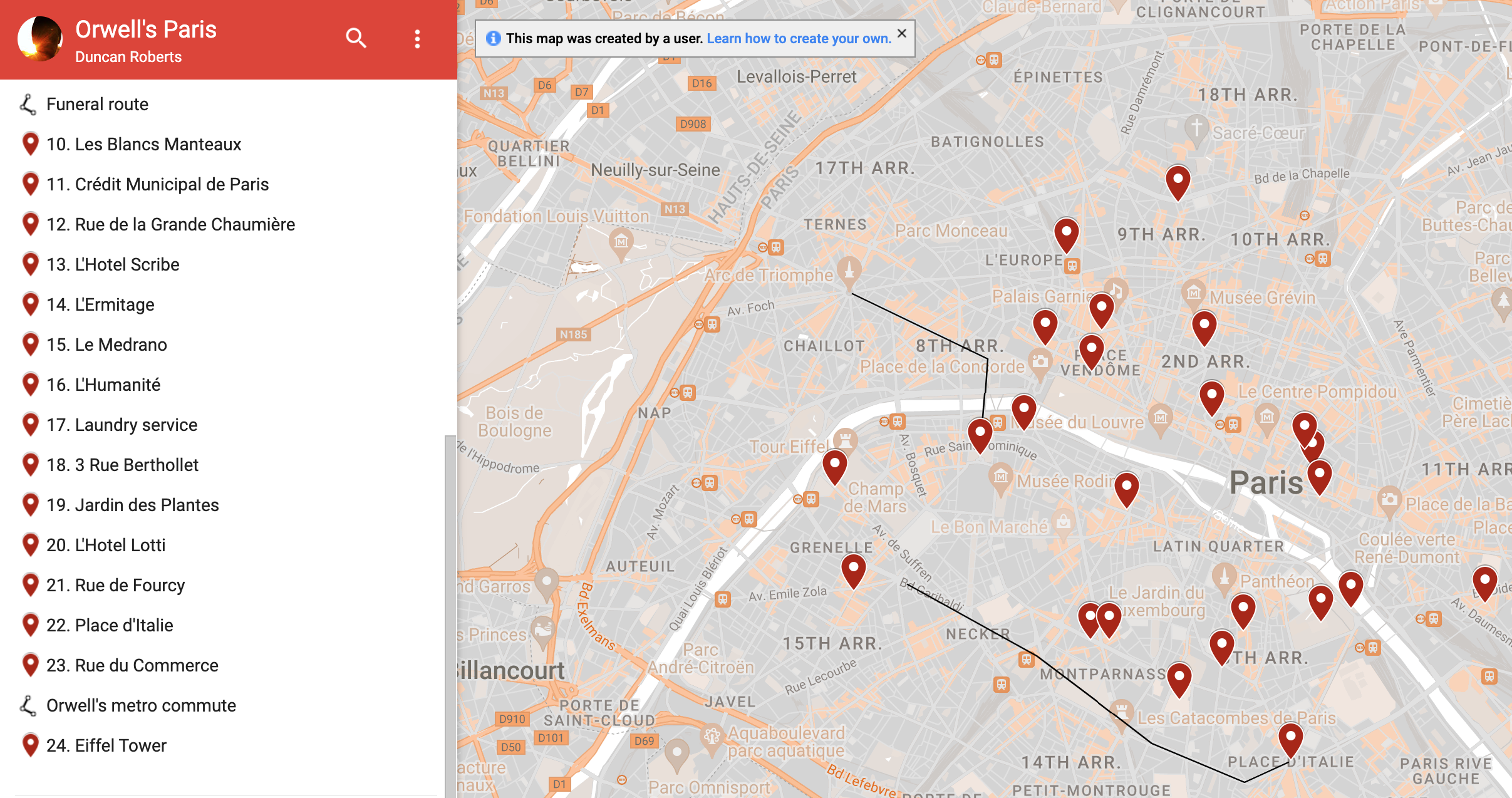

- This map of Orwell’s Paris identifies some previously unidentified locations.

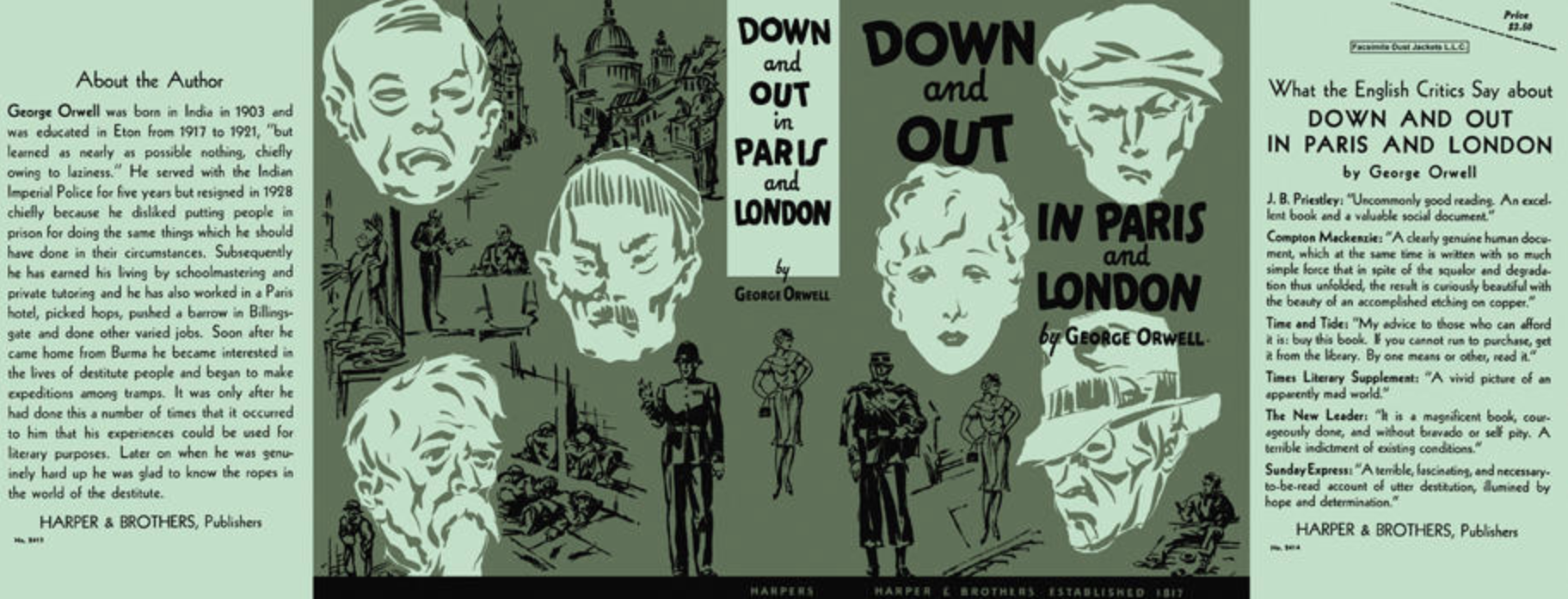

George Orwell: journalist, writer… Paris city guide? Well, not quite. Or at least not in person. The author of Animal Farm and 1984 spent the early days of his literary career in Paris, and much of his stay can be reconstructed from his work, notably his first full-length book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933).

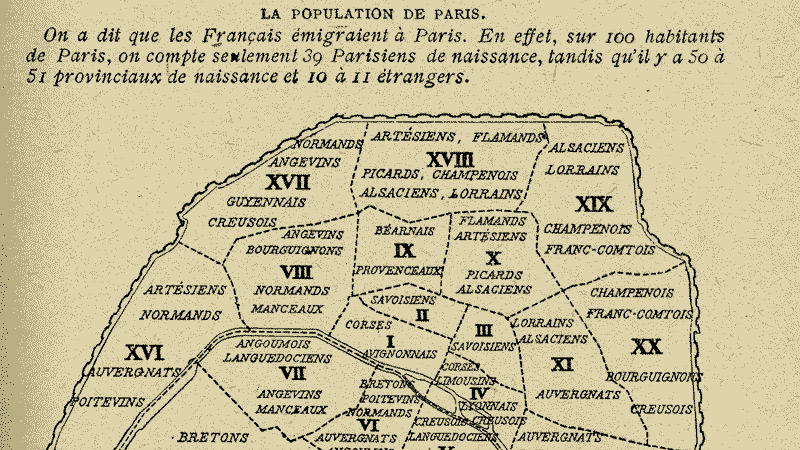

In June 1928, Orwell — then still known as Eric Arthur Blair — moved from London to Paris, with the aim of learning French, living cheaply, and writing novels. That didn’t quite work out: although he had some success writing shorter-length journalism, he was forced to take up menial jobs in order to survive. However, you could call it providential (if not intentional) slumming. This provided material for what would become the Parisian half of Down and Out. In December 1929, after a year and a half in Paris, Orwell returned to England.

Orwell’s Parisian days have now been pinned to a Google Map by Duncan Roberts and Darcy Moore. Duncan Roberts is a “writer and literary detective” based in Paris. His forthcoming book Orwell and the Russian Captain focuses on the real people and places in Orwell’s first book — many obscured, often for fear of libel. Darcy Moore has written extensively on Orwell and is currently preparing a book provisionally titled Orwell in Paris: The Making of a Writer.

If anyone is qualified to show us around Orwell’s Paris, it’s these two. Their map is a handy guide for exploring the city through the eyes of the budding writer, whether you are able to do so in person or via Street View. The numbered pins allow us to retrace the writer’s footsteps, as he made his way through the nether parts of the City of Lights. Below is a short overview. For more, check out the map itself, the websites of both writers, and their upcoming books.

1. Gare Saint Lazare

Roughly five months after the end of his days as a policeman in Burma, this is where Orwell arrives in Paris, and he had to register with the French police. His first destination in the city would have been his aunt, who lived in the 12th arrondissement.

2. 14 Avenue de Corbera

The address was shared by his aunt Nellie Limouzin and her soon-to-be husband Eugene Adam, who shared a passion for socialism and Esperanto. Orwell stayed here until he found lodgings in the Latin Quarter.

3. 6 Rue du Pot de Fer

Orwell’s home base for most of his stay was the Hôtel des Bons Amis in the narrow Rue du Pot de Fer. In the book, it is renamed Hôtel des Trois Moineaux and moved to the non-existent Rue du Coq. These days, the hotel is gone. The ground floor is occupied by Café Planet-chicha, a hookah bar.

4. Montparnasse

What Greenwich Village was to New York and Soho to London, Montparnasse was to Paris: the glamorous cultural epicenter, drawing in artistic hopefuls from far and wide. Although Hemingway and most of the “Lost Generation” had left by the time Orwell arrived, famous cafés like Le Dome and Le Select were still doing brisk business.

5. Les Halles

From the mid-19th century until it was demolished in 1970, the Marché des Halles served as central Paris’s fresh market. After losing his only English-language pupil, Orwell came here at the crack of dawn, hoping to find work as a porter. His job interview consisted of lifting a large basket. He failed.

6. Les Deux Magots

This was one of the places m’as-tu-vu (that is, “places to be seen”) for the literary crowd. Orwell saw James Joyce have lunch there but didn’t dare disturb him. In 1945, back in Paris as a war correspondent, Orwell arranged to meet Albert Camus here. Unfortunately, Camus was ill and didn’t show.

7. The river Seine

Orwell borrowed a fishing rod and used bluebottles as bait, but he didn’t catch any fish from the Seine, claiming they had all grown “cunning during the Siege of Paris” (in 1870-71). He later claimed that he had crossed the Seine 11 times in one day, while looking for work.

8. Hôpital Cochin

Orwell was admitted to this charity-run hospital for the poor in April 1929, suffering from flu. Although he left his stay here out of Down and Out, it formed the basis for a separate essay called “How the Poor Die.”

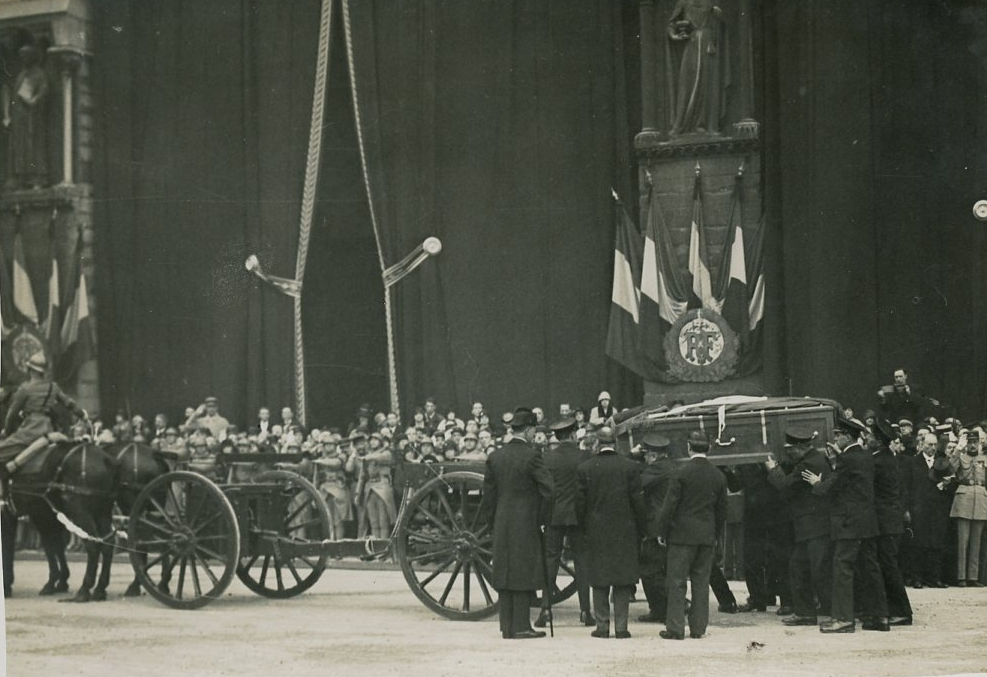

9. Les Invalides

A few days after discharging himself from the hospital, Orwell attended the funeral of Maréchal Foch, the Supreme Commander of the Allied forces during World War I. Foch was granted the honor of a full carriage procession from the Arc de Triomphe to Les Invalides.

10. Blancs Manteaux

Orwell goes to the Marais, a predominantly Jewish area of Paris, in search of Boris, the Russian captain he met a few months previously at the Hôpital Cochin. He is hopeful that Boris will help him find a job: “I even squandered two francs fifty on a packet of Gauloises Bleues… In the morning I walked down to the Rue du Marché des Blancs Manteaux.”

11. Le Mont-de-Piété

Then as now, this is the location of a state-run pawnbroker, where Orwell pawned off his few possessions in exchange for a few francs for food. Then as now, “One went through grand stone portals marked, Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” Mont de piété, French for “pawnshop”, literally means “Mountain of Piety.” It is a mistranslation of the Italian monte di pietà, meaning “charity amount.”

12. Rue de la Grande Chaumière

This was the address of Ruth Graves, an American artist who had lived in Paris since 1924. Orwell was friends with her and discussed the first sketches of Down and Out with her. Decades later, upon hearing Orwell was ill with tuberculosis, she offered to send him experimental medicine, prohibited in England.

13. Hotel Scribe

Boris had worked at the Scribe, a five-star hotel next to the Opera Garnier. He and Orwell waited in front, for a job that never materialized: “We went to the Hotel Scribe and waited an hour on the pavement, hoping that the manager would come out, but he never did.” This is where Orwell stayed in 1945 and may have met Hemingway.

14. L’Ermitage

Yet another restaurant, this one on the Rue Boissy d’Anglas, where Boris and Orwell sought and failed to find work. It was one of the more reputable of the hundreds of Russian establishments in Paris, fuelled by the wave of Russians fleeing Bolshevism. Picasso, Satie, and Cocteau were among its many famous guests.

15. The Medrano

“Once we answered an advertisement calling for hands at a circus. You had to shift benches, clean up litter and during the performance, stand on two tubs and let a lion jump through your legs.” Although the latter is hard to believe, this must have been the Medrano, in the ninth arrondissement, demolished in 1971.

16. L’Humanité

“… the Paris police are very hard on Communists, especially if they are foreigners, and I was already under suspicion. Some months before, a detective had seen me come out of the office of a Communist weekly paper, and I had had a great deal of trouble with the police.” This must have been L’Humanité, the newspaper that, according to recently released secret service reports, Orwell read regularly. Back then, it was located at 142 Rue Montmartre, now home to a locksmith.

17. “Laundry service”

At an undisclosed location south of the Seine, near the Chamber of Deputies, Boris and Orwell met with a secret Russian society. Orwell was hoping to write some paid articles for a Moscow newspaper. The society is fronted by a laundry service. “Why have you come here without a parcel of washing? Bring a good large bundle next time. We don’t want the police on our tracks.”

18. 3 Rue Berthollet

The address of Tambour, a bilingual (English-French) modernist journal, edited and published by the American Harold J. Salemson. Tambour had a circulation of about 1,500 copies, and its subscribers included James Joyce and Jean Cocteau. Salemson translated Orwell’s first professional writing, “La Censure en Angleterre”. It was published in the October 6, 1928 edition of Le Monde.

19. Jardin des Plantes

Being broke in Paris offers excellent opportunities to enjoy the many excellent public gardens. Orwell hung out at the Jardin de Luxembourg, the Tuileries, and the Jardin des Plantes. Of the latter, he later wrote in a letter, “I used to love it, though there was really nothing of interest except the rats, which at one time overran it & were so tame that they would almost eat out of your hand.” (See also #914)

20. The Lotti

Orwell finally got a job as a plongeur (dishwasher) at the Lotti, a luxury hotel in the eighth arrondissement, disguised as “Hotel X” in Down and Out. It is still there, at 7 Rue de Castiglione.

21. Le Fourcy

“Sometimes half a dozen plongeurs would make up a party and go to an abominable brothel in the Rue de Siéyes… it was nicknamed le prix fixe.” The street name is made up. This probably was Le Fourcy, a brothel at 10 Rue de Fourcy, half an hour’s walk from the Lotti.

22. Place d’Italie

“Every morning at six I drove myself out of bed, did not shave, sometimes washed, hurried up to the Place d’Italie and fought for a place on the metro.” This metro station was a 20-minute walk from Orwell’s hotel. The trip on line 6 would take another 20 minutes. Orwell would get off at Cambronne on the Boulevard Garibaldi. From there, it was a short walk to L’Auberge du Jehan Cottard.

23. L’Auberge du Jehan Cottard

Another disguised location, half-identifiable. Orwell fictitiously named the restaurant after a poem by François Villon, but placed it on the Rue du Commerce, which is real enough. He was certain the venture would fail. Yet despite his misgivings, he left the Lotti and followed Boris, who was appointed head waiter. “And, strange to say, in spite of all this filth and incompetence, the Auberge de Jehan Cottard was actually a success.”

24. Eiffel Tower

Throughout the book, Orwell focuses on gritty, working-class Paris, omitting virtually all of the city’s famous landmarks. But he does mention the Eiffel Tower, “flash(ing) from top to bottom with zigzag skysigns, like enormous snakes of fire.”

For more on Orwell in Paris, check out the websites of Duncan Roberts and Darcy Moore. Check out their map in more detail here.

Update 6 May 2022: a previous version of this map did not yet identify the street in which the Auberge de Jehan Cottard (#23) was located, nor did it mention the Eiffel Tower (#24). Many thanks to Mr Moore for informing me of the changes.

Strange Maps 1125

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.