InterContinental Railway: All aboard the train from New York to Paris — via Siberia

- Snowpiercer is fiction, and so is this other globe-spanning train. But the plans for it are serious.

- The ICR would connect Eurasia to the New World, via a 70-mile Bering Strait Tunnel.

- Will it ever happen? Only if we get the geopolitics, financing, and engineering right.

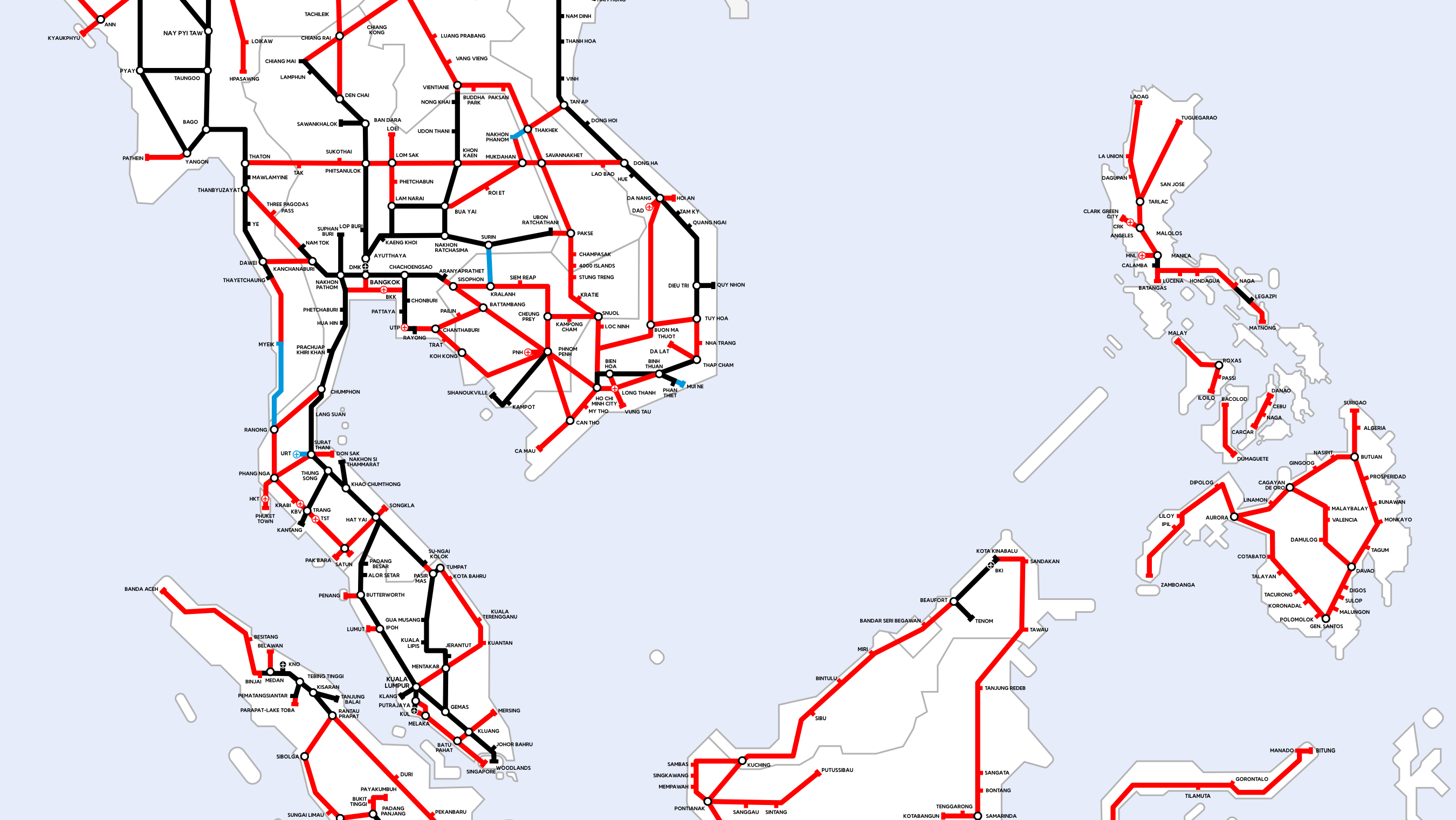

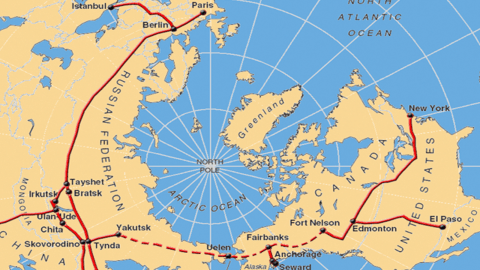

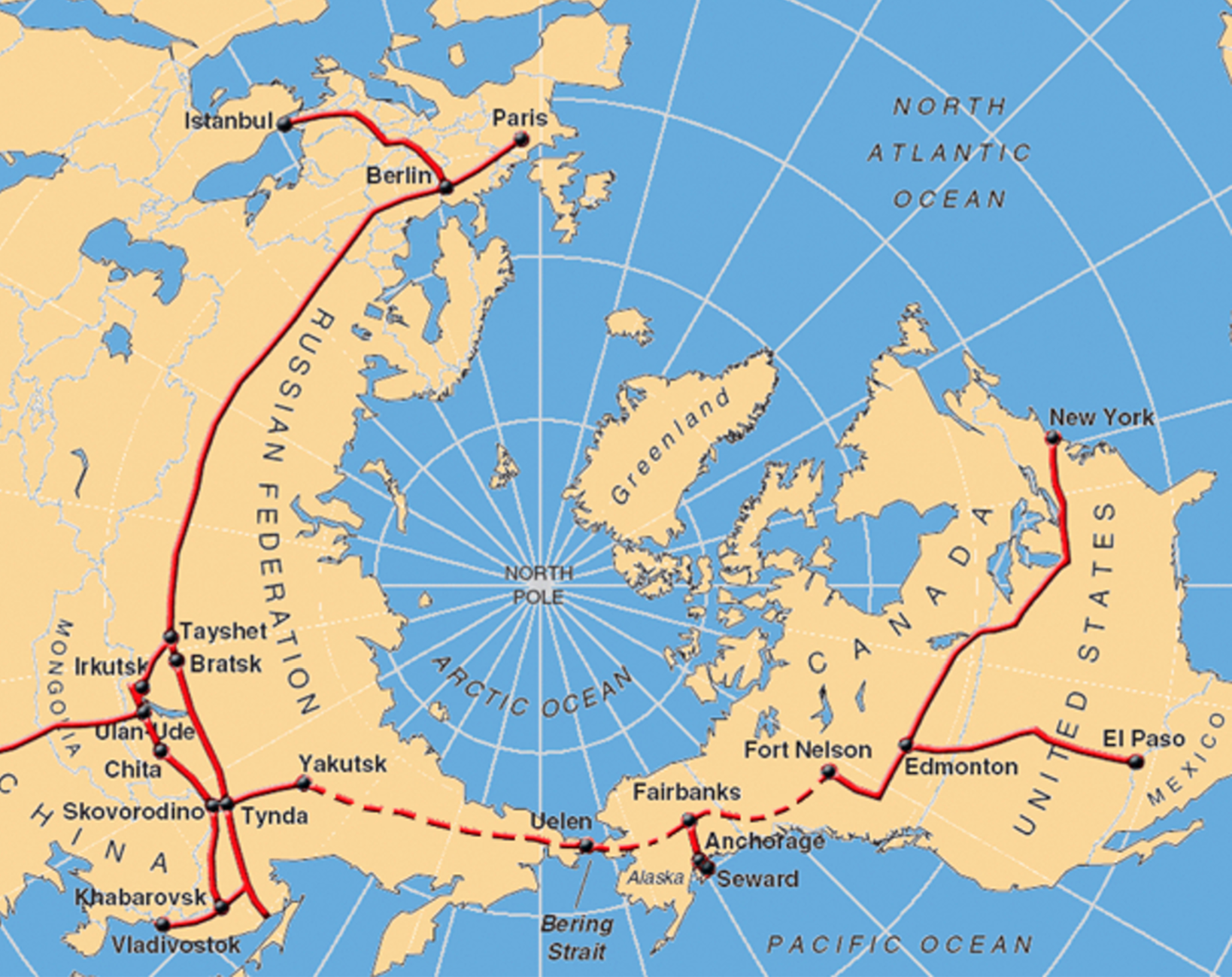

Snowpiercer is a fictional train, its 1,001 cars carrying humanity’s last survivors as it endlessly loops a frozen Earth. Shown on this map, the InterContinental Railway (ICR for short) doesn’t quite go all the way around — but then again, it isn’t quite as fictional.

Centuries of “peace, progress and prosperity”

Both the Snowpiercer movie and series were based on Le Transperceneige, a French graphic novel from 1982. The ICR, on the other hand, is being proposed by engineers and entrepreneurs, who very much believe that it can and should become reality.

If it does, you’ll be able to take a train from New York to Paris, or from Vladivostok to El Paso. The ICR would create the physical conditions for centuries of “peace, progress, and prosperity,” as the project developers’ prospectus hopefully promises.

The ICR proposal predates by a few years the current war in Ukraine, and Russia’s consequent geopolitical isolation from both Europe and North America. Obviously, those circumstances would have to change drastically for such a plan to be seriously considered by all parties involved.

5,500 miles of new railroad

But even if a few years down the line Russians, Americans, and Europeans were on the same page again and this plan was approved, the logistics still would be phenomenally daunting.

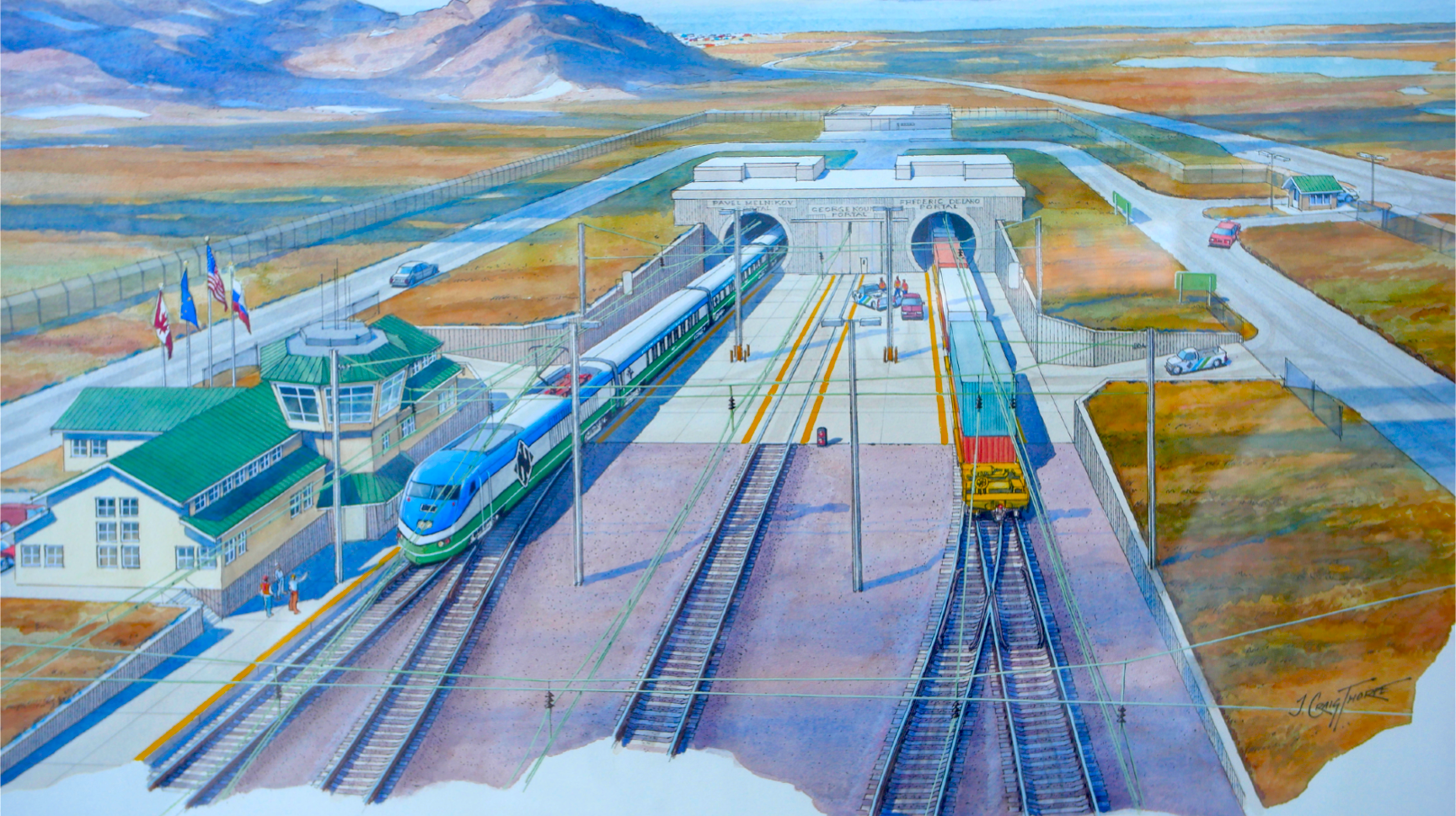

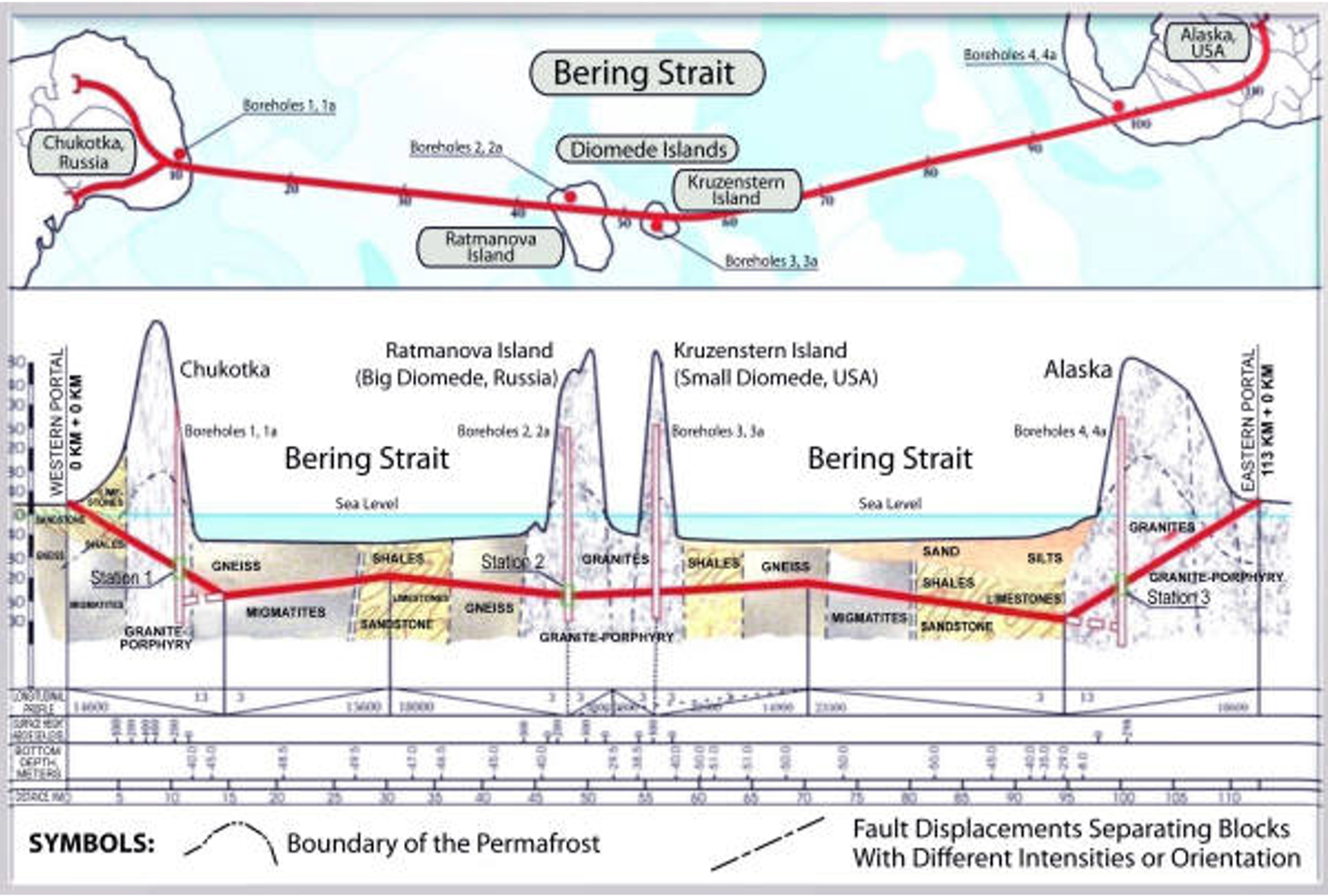

For starters, the ICR would need nearly 5,500 miles (8,850 km) of entirely new railroad (the dotted lines on the map), from Yakutsk in eastern Siberia to Fort Nelson in northwestern Canada. And crossing the Bering Strait would involve building the world’s longest railway tunnel, 70 miles (113 km) long.

That’s more than double the length of the Seikan Tunnel connecting the Japanese islands of Honshu and Hokkaido, which at 33.5 miles (54 km) is currently the world’s longest underwater rail tunnel.

It would have to be built under adverse conditions, too. Construction in the harsh near-Arctic climate can only take place in the annual four-month warm weather window, and almost anything and anyone needed to dig the tunnel would need to be shipped in from very far away.

The ICR: cheaper than the ISS?

On the other hand, the developers say the local geology means that the Bering Strait Tunnel would be “easier to construct than English Channel Tunnel.” Another bit of luck: the ventilation shafts needed for a tunnel of this length could conveniently be placed on the Diomede Islands, almost exactly halfway in the Bering Strait. (Big Diomede is Russia’s easternmost territory; Little Diomede is a few miles away and part of the U.S.)

The price tag for the entire project would be more than $100 billion dollars. Still, that’s “less than the investment in the temporary International Space Station,” the project developers say. Plus, “[those] costs can be spread over the 100-to-200-year lifetime of the infrastructure assets.” But mainly, the ICR “creates an opportunity for peaceful cooperation between the U.S., Canada, Russia, China,” and other countries and will “stimulate global economic activity over the next 100 to 200 years.”

The ICR could carry as much as 100 million gross tons (MGT) of goods across the Bering Strait annually, which is the equivalent of about 3% of global trade. And it could do so in less than half the time, and with considerable cost savings, by eliminating two port transfers for the goods involved.

An opportunity, or a threat?

This would boost trade between Canada and the U.S. on one side, and Russia, China, and Europe on the other. Additional rail links could integrate markets further afield, including Mexico and the Koreas. Last but not least, transport via the electrified railroad would eliminate a lot of CO2 emissions caused by ocean shipping.

All in all, it’s a great idea, but it is unlikely to survive contact with reality, at least for the foreseeable future. Just one example: Russian rail operates on a broader gauge (4 ft, 11.8 in or 1520 mm) than its counterparts in Europe and North America, which use the standard gauge (4 ft, 8.5 in or 1435 mm). This is by design rather than accident: The gauge difference is meant to obstruct any invasion of Russia by rail.

Overcoming this issue would mean building dual-gauge tracks or wheel gauge-changing technology, at a considerable cost in money and convenience. But even in the age of hypersonic intercontinental missiles, many in Russia would see such a move as a geopolitical threat rather than an economic opportunity. It may be a while before that changes. So it seems that for a few more years at least, the ICR will keep Snowpiercer company in the realm of fictional trains.

For more on the InterContinental Railway, check out their website.

Strange Maps #1199

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.