In Europe, trust in others depends on location

- Citizens of the EU were asked if they trusted people in their area and members of parliament.

- The answers show remarkable similarities and differences, including geographical ones.

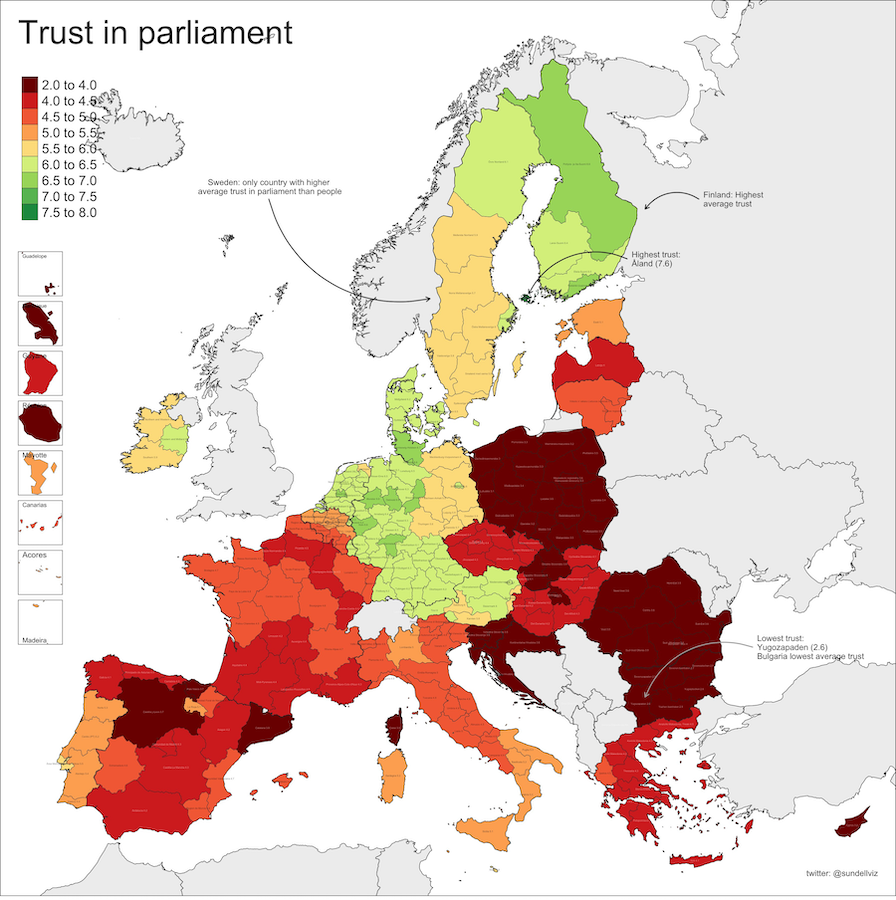

- With the exception of one country, trust is higher in locals than in politicians.

How much do you trust the people in your local area? And the politicians in your national parliament? From October 2020 to February 2021, these were among the questions put to citizens across the 27 member states of the European Union. Their answers form the basis of the 2021 European Quality of Government Index.

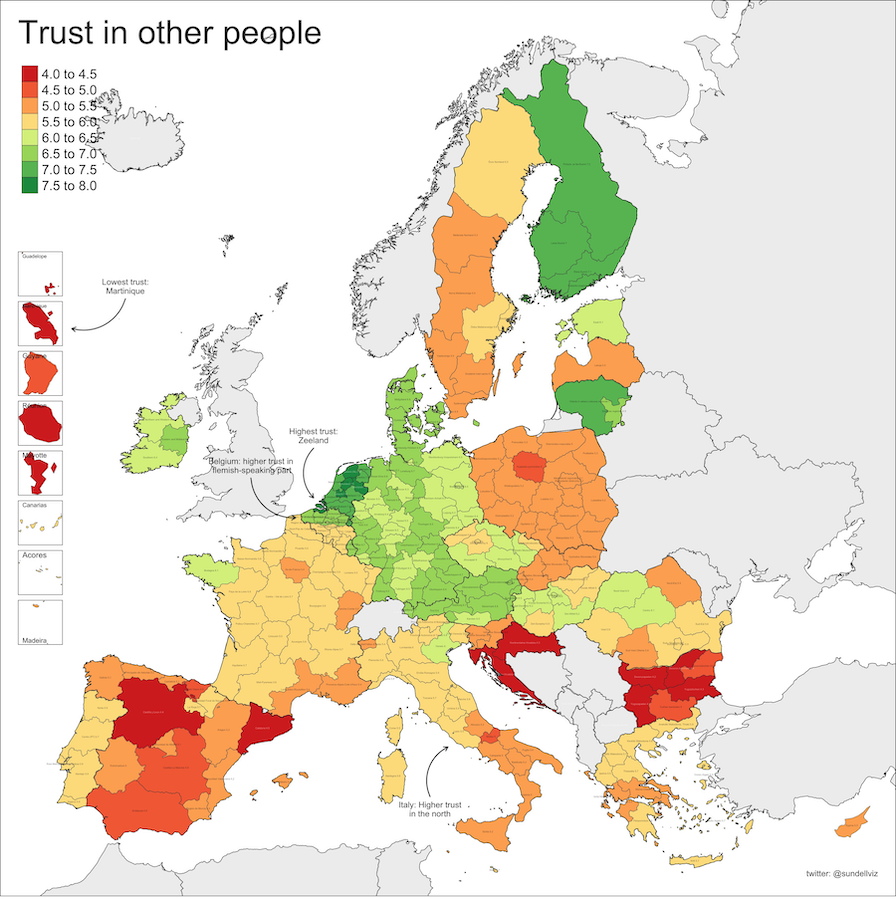

From Zeeland to Martinique

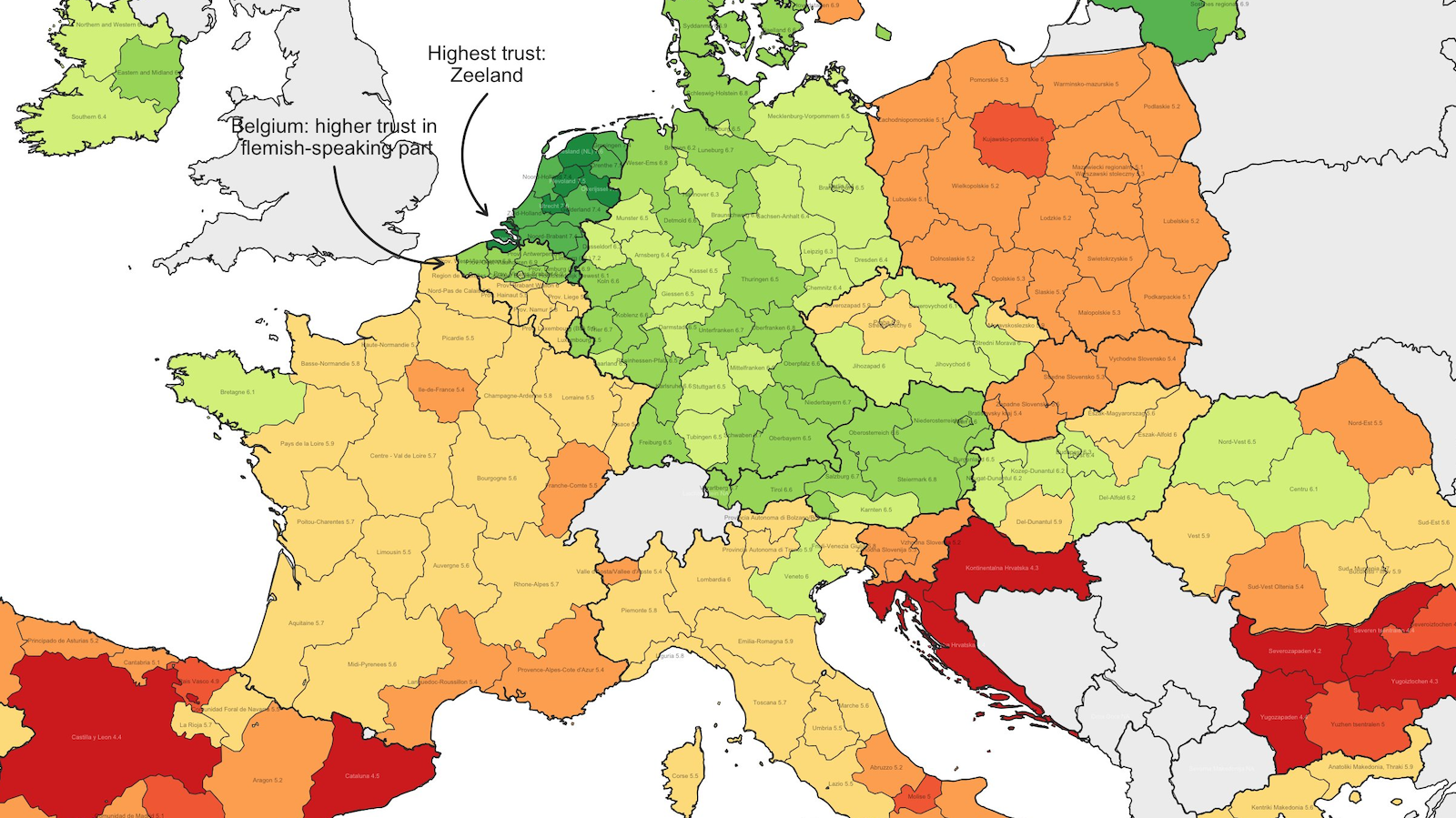

Those answers were also used for these two maps by Anders Sundell, a political scientist at the University of Gothenburg. He translated those levels of trust into color codes: darker green means higher, darker red is lower, and orange is meh.

Some preliminary findings:

- In 26 member states, levels of trust in local people are higher than in national politicians. The only exception is Sweden, where it is the other way around.

- Trust of either kind is generally higher in Europe’s north and west, while lower in its south and east.

- Across the entire EU, trust in locals is highest in the Dutch province of Zeeland and lowest in Martinique, a French overseas department in the Caribbean.

- Trust in politicians is highest in Åland, an autonomous region of Finland. And it is lowest in Yugozapaden, the southwestern region of Bulgaria that includes the capital, Sofia.

Let’s have a closer look at both maps. First, the one showing levels of trust in other people. The question was: “On a 1 to 10 scale, with 1 being ‘no confidence at all’ and 10 being ‘complete confidence’ to do the right thing, how much confidence do you personally have in other people in your area?”

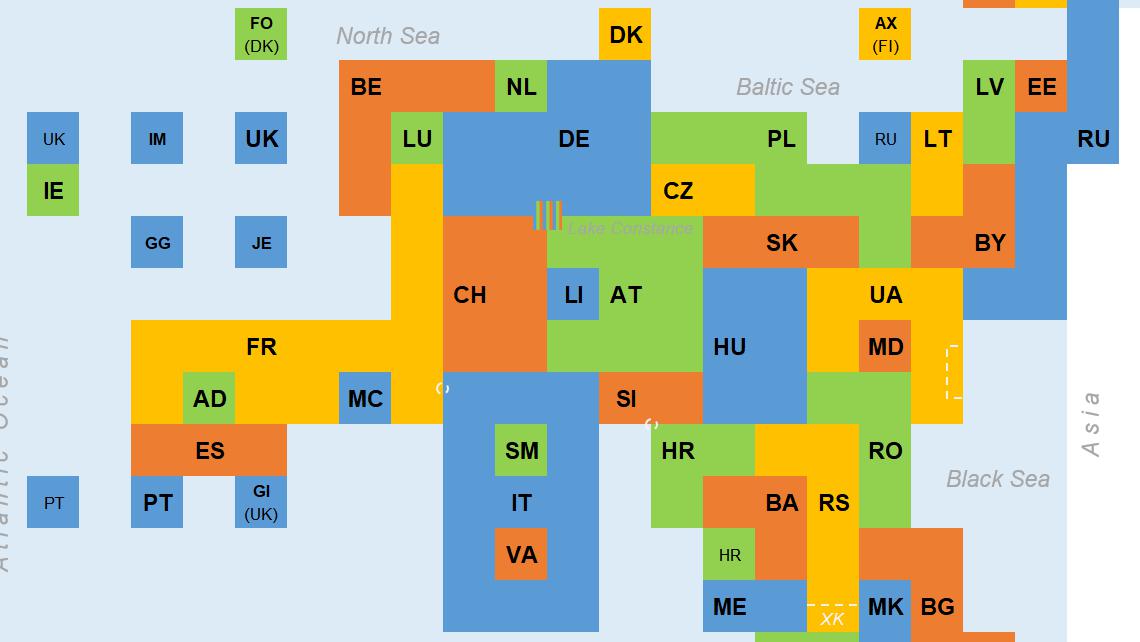

So-called NUTS 2 regions — a standard subdivision used in EU statistics — with a score of 6 or higher are colored green. Relatively few countries are entirely green:

- Four are in the Nordics and Baltics: Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Denmark. Sweden and Latvia are the odd ones out.

- There’s a contiguous block of four more countries in Western Europe, consisting of Germany, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Austria. Confidence levels are extremely high in the Netherlands and noticeably lower in the former East Germany.

- Ireland is the only other EU member state that’s entirely green.

Belgium’s language border lights up

Other countries substantially or partly green include:

- Belgium, where the color difference lights up the language border, with green areas in the Dutch-speaking north and orange ones in the French-speaking south.

- The Czech Republic and Hungary, which are roughly evenly split. The Czech capital Prague is in the orange camp, but the Hungarian capital Budapest is in the green one.

- The only other green zones are Brittany in France, two Romanian regions that correspond with Transylvania, and the Italian region of Veneto (containing Venice).

On the other side of the spectrum:

- Croatia and Bulgaria stand out as being entirely and almost entirely dark red (i.e., 4.5 or below), respectively.

- The Spanish regions of Catalonia and Castilia y Leon are the only other NUTS 2 areas scoring darkest red.

- Latvia, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia all score entirely below 5.5.

- Spain is spared that fate by Navarra and La Rioja, two small northern regions scoring just over 5.5; but overall confidence is visibly lower than in most other member states.

Dublin and Madrid go against the grain

A few interesting regional divides:

- In Italy, neighborly trust is lower in the south but higher in the north.

- In Greece, that trust is lower in the central region (which includes Athens) but higher in both the north and south.

- In fact, trust in your local fellow human is often lower in regions that contain the national capital, often the country’s largest city (see also Poland, France, Sweden, Lithuania).

- Curiously, the reverse is true in a number of countries, notably Ireland and Spain.

For the second map, the question was: “On a 1 to 10 scale (…), how much confidence do you have in (your country’s) parliament?” When substituting ordinary humans for the more specialized subset of national politicians, it is striking how the general divides of the first map still apply, but it’s as if someone upset the color balance, emphasizing the reds over the greens.

Says Mr Sundell: “I used the same color scale and breaks as in this other map, to make comparisons easier. But I had to add a lower category!” Clearly, EU citizens don’t think too highly of their parliamentarian representatives.

The East is red (again)

The level of confidence is especially low in Eastern Europe:

- Six countries fall entirely within that lower category (2 to 4 out of 10), five from the (former) Eastern Bloc: Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovenia, and Croatia. The other one is Cyprus.

- Including the lowest but one category (4 to 4.5) adds the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Latvia.

- That leaves out only Lithuania and Estonia of the former Communist Bloc countries that have now joined the EU — although only Estonia manages a score that’s better than half, and then only barely: 5.1 out of 10.

The picture is only somewhat better in the southern part of what used to be called Western Europe:

- Spain’s three darkest spots are the two regions from before, plus the Basque Country. Only La Rioja manages a score better than half; the rest of the Spanish regions languish between 4 and 5.

- Portugal does noticeably better, but doesn’t exceed 5.5.

- Except for Lombardy in the north, trust in Italy is below 5, except for the country’s southern regions, which hover between 5 and 5.5.

- In France, Corsica’s distrust is highest. The entire country remains below 5, with darker regions in the south and in a band across the north, from the English Channel to the Swiss border.

- Belgium’s language border is blurring again, with some of the south climbing above 5; but the entire country remains below 5.5.

Line up the usual suspects

For some reason, 5.5 out of 10 seems to be a fairly strict divider. Eighteen countries score below this level of trust, not just nationally, but for each of their regions. And eight countries have a higher score — again, not just overall, but also regionally. The only exception is Portugal, where the Lisbon Metropolitan Region scores 5.5, while the rest of the country stays between 5 and 5.5.

- It’s the usual suspects that have the highest scores: Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Luxembourg, Austria, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland.

- In Germany, the divide between the regions in the 5.5 to 6 bracket and those scoring higher aligns perfectly with the former border between East and West Germany.

- Sweden’s extraordinary score — higher trust in politicians than locals — has been speculatively attributed to the country’s unique approach to the coronavirus pandemic, which has emphasized personal responsibility over nationally imposed restrictions.

These maps were found on Mr Sundell’s Twitter feed. For more on this topic, go to the Quality of Government Institute at the University of Gothenburg. And check this page at the QoG Institute for some great map visualization tools for QoG data.

Strange Maps #1112

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

Follow Strange Maps on Twitter and Facebook.