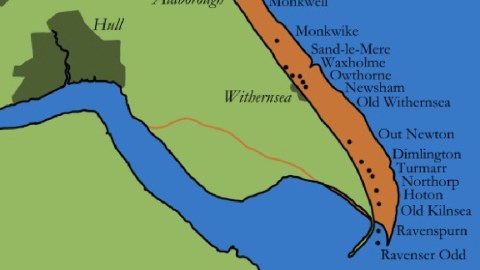

A Map of Europe’s Fastest-Eroding Coast

Watch the grey waves pound the Yorkshire coast anywhere between Flamborough Head in the north and Spurn Head in the south, and you get a false sense of timelessness. This forty-mile stretch of beach is the fastest-eroding coastline in Europe. The sea out there used to be land, and the land you’re standing on will soon be eaten by the waves.

Every year, the sea gains an average of five feet on the land. In late-Roman times, the surf broke three miles further east. The strip of land that fell into the North Sea in the intervening centuries contained at least twenty-nine villages and towns.

This part of the East Riding of Yorkshire, bounded by the North Sea in the east, the estuary of the Humber in the south and the Yorkshire Wolds in the north and west is known as Holderness (1). It is flat and formerly swampy, drained from the Middle Ages onward. Much of the underground, and of the beachside cliffs, is made up of soft clay, which erodes easily.

Hence the rapid marine erosion, which sweeps away as much as two million tonnes of soil a year between Flamborough and Spurn Heads (2), which are made of sterner stuff. The coast’s loss is Spurn Head’s gain. About three percent of the eroded material is deposited there. Spurn Head keeps growing as the coast to the north of it keeps shrinking.

This map shows the present coastline in green, the lands lost since late-Roman times in orange-brown, and in that strip the names and locations of more than two dozen places swallowed by or abandoned to the waves, from Wilsthorpe close to Bridlington in the north, to Ravenser Odd in the south, not far from Spurn Head. In between, vanished towns with resonant names that have nevertheless been wiped from other maps and most memories: Hartburn, Colden Parva, Monkwell, Sand-le-Mere, Out Newton.

Coastal erosion continues, despite coastal defences that include a concrete seawalls and timber groynes – long structures sticking into the sea to prevent the beach being washed away by longshore drift. These have had limited benefits, and sometimes even adverse effects. Add to that a geological process called isostatic recoil, which means the area is sinking at a rate of thee millimetres per year. Combined with rising sea levels due to climate change, the North Sea could be half a metre higher here by 2050.

The map shown here is based on T. Sheppard’s, The Lost Towns of the Yorkshire Coast, published in 1912. This version was produced by Dr. Caitlin Green for an article on her website, in which she focuses on what was perhaps the shortest-lived, but certainly the best-documented and arguably the most interesting of the lost coastal towns of Holderness: Ravenser Odd.

Ravenser Odd was an island town founded on a spit of land thrown up by the sea in the 1230s. An Inquisition report from 1290 states that:

Forty years ago, a certain ship was cast away at Ravenser Odd, where no house was then built, which ship a certain man appropriated to himself, and from it made for himself a hut or cabin, which he inhabited for so long a time that he received ships and merchants there, and sold them food and drink, and afterwards others began to dwell there.

Rising from the sea, Ravenser Odd grew by it and prospered from it, before the sea swallowed it up again – all in not much more than a century. The exact location of the island-town is uncertain. It is usually situated east of where Spurn Head is today, at a distance of more than a mile from the mainland shore.

Ravenser Odd grew busy and rich fast. In 1251, it obtained a charter for a market and a fair. By 1290, the rival port of Grimsby, on the southern bank of the Humber, suffered so much from the competition that it accused Ravenser Odd of piracy, and was partially abandoned. In 1299, the town received a borough charter from Edward I and a thirty-day fair. Ravenser Odd sent representatives to Edward’s Parliament. The busy port appears on a map c. 1325 by famous Italian cartographer Pietro Vesconte.

But the sea was eager to take back the land she had thrown up. From the mid-fourteenth century, erosion started eating away at the island. In 1346, it was reported that the town being ‘daily diminished and carried away’. Around that time, more than 200 buildings and properties had already been lost to the sea. The destruction reached apocalyptic levels in the next years, according to contemporary reports:

The inundations of the sea and of the Humber had destroyed to the foundations the chapel of Ravenserodd, built in honour of the Blessed Virgin Mary, so that the corpses and bones of the dead there horribly appeared, and the same inundations daily threatened the destruction of the said town.

Not long after 1355, the year in which the deceased of Ravenser Odd had been reburied in dry land at Easington, the whole town was annihilated by the river Humber and the North Sea. The last mention of the town dates from 1358, when its ships are mentioned as the means transport for wool from Boston to Flanders. By 1362, it was most likely abandoned, because some men were brought before court for ‘throwing down and rooting up the timber of the staithes at Ravensrod’, an indication that the town was derelict. Hull took over the drowned city’s seaport role.

Hull has prospered while Ravenser Odd has vanished from history. But the city on the Humber should not get too complacent. The following two maps show two possible end points for coastal erosion in Holderness, at some point a few millennia into the future. Hull survives in scenario A, but scenario B is likelier.

Map A assumes no significant further rise of sea levels. The natural end-point of the erosion will create a wide bay between Flamborough Head and Cromer in Norfolk – two hard headlands. Map B takes into account the likelier scenario of significant sea level rise. The result: the coastline retreats much further east, back to its pre-glacial position. In this scenario, Hull goes the way of Ravenser Odd, albeit a few thousand years into the future.

Maps found here at the website of Dr. Caitlin R. Green, one of whose maps was used earlier on this blog (see #715)

Strange Maps #830

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) Holderness – the name may derive from the Danish hold, the name for a nobleman with considerable territorial possessions. Ness may refer to a nose-shaped promontory jutting out into the sea. William the Conqueror granted the lordship of Holderness to Drogo de la Beuvrière, a Flemish associate of his. Drogo fled England after the death of his wife, whom he may have poisoned by accident. Before leaving, he secured a loan from William. Only after he left did William learn of the death of Drogo’s wife, his niece. He forfeited Drogo’s lands and titles and ordered his arrest, but he had disappeared, possibly back to Flanders.

(2) In Spurn Head, part three of Will Self’s Walking to Hollywood, the rapid erosion of the Holderness Coast is used as a metaphor for the effects of Alzheimer’s disease.