Another New England — in Crimea

“I don’t want to change the world”, sang Billy Bragg in the early 1980s, “I’m just looking for a New England.” Some nine centuries earlier, that same thought must have crossed the mind of an obscure Saxon nobleman as he sailed away from his recently vanquished homeland.

The story goes that in 1075, a Siward, earl of Gloucester led a flotilla from England into the Mediterranean. Onboard was the flower of England’s native aristocracy, disenfranchised by the Norman Conquest of 1066. They reached Constantinople, gaining permission from the emperor to settle in Byzantine lands on the Black Sea’s northern shore — if they could reconquer them.

They did, and founded a Nova Anglia, the towns of which echoed the names of the ones the settlers had left behind. No trace of the colony remains today, but this New England (on the Crimean peninsula, and immediately to its east) must have survived for at least a few hundred years. Well into the 14th century, the New Englanders’ annual Christmas greetings to the emperor were conveyed “in their native language, English.”

Chances are you’ve never heard of this earlier version of New England — a geographical concept now firmly associated with the Northeastern U.S [1]. That’s because the existence of Nova Anglia is only mentioned by two medieval texts, both far removed in time and place from their subject, and both possibly derived from a single source, since lost.

Hence New England’s apocryphal afterlife, even though circumstantial evidence at least partially compensates the lack of tangible remains.

A home far away from home: England, New England, and the long voyage in between.

The older of both texts is the Chronicon Universale Anonymi Laudunensis, written in 13th-century France, referring to an English emigration of 4,350 individuals aboard 235 ships, arriving in Constantinople in 1075.

The later text is the Játvarðar Saga (the Saga of Edward the Confessor), written in Iceland in the 14thcentury. It mentions the death of Denmark’s King Sweyn II Estridsson (in 1074, or 1076) as the catalyst for the emigration. Sweyn had been the Saxon nobility’s last hope of liberation from the Norman yoke.

The Norman conquerors, no doubt glad to be rid of this troublesome bunch, may have directed the English émigrés to recent conquests by their kinsmen in the Mediterranean. En route to Sicily, the English fleet ravaged Ceuta, seized Majorca and Minorca, but eventually laid a course for Constantinople after hearing of heathens besieging the imperial capital.

If, as specified by the Chronicon, the English reached Constantinople in 1075, the emperor at the time was Michael VII (1071-’78) and the siege they helped relieve was of the Seljuk Turks — making sense of the Saga mentioning “heathenfolk.”

But both sources claim Alexius I (1081-1118) was the emperor when the English arrived. That is but one of the inconsistencies in the texts [2], sometimes also with regard to each other. The Chronicon leaves the Danish king unnamed, nor specifies the flotilla’s route through the Mediterranean. It replaces Sicily with Sardinia and renames Sigurðr (as Siward is called in the Saga) as Stanardus [3].

The date problem may be due to the fact that disgruntled Saxons had been travelling to Constantinople before the larger migration, joining the Varangian Guard [4].

But the main elements of the story are the same in both texts: the ships and its noble crew, their aid to the emperor of Constantinople, and his grateful offer to include them in the Varangian Guard. Other sources support the story so far, but what follows is only in the Chronicon and the Játvarðar Saga. The latter says that:

“Earl Sigurd and the other chiefs begged emperor Alexius to give them some towns and cities which they might own and their heirs after them. The emperor knew of a land north of the sea, which used to be ruled by his predecessors, but had been won by the heathens, who lived there still. The king granted this land to them and their heirs, if they could win it.”

“Some Englishmen stayed in Miklagarðr [‘the great city,’ i.e., Constantinople], While Earl Sigurd and others sailed north to that land and had many battles there, winning the land and driving away those that lived there before. They called their new land England. Its pre-existing and newly built towns they named after English cities – London, York, and others. The land lies six days and nights sail east and northeast from the City. The English have lived there ever since.”

The Chronicon adds that a tax collector sent by the Emperor Alexius to the Angli orientales (Eastern English) was killed by them, after which the English remaining in Constantinople fled to New England, where they took up piracy.

Things must have been patched up again between the New Englanders and the emperor, as they continued to supply men to the Varangian Guard — the last reports of Englishmen in the Guard date from 1404.

But where exactly was their new home? The sailing distance and time mentioned by the Saga corresponds with Cherson, the Byzantine province on the Crimea, which was lost in the late 11th century to an invading force of Cumans, a Turkic nomadic people.

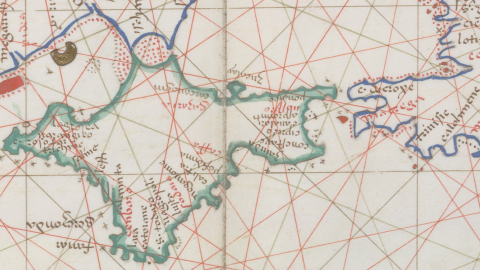

The possibility that the English retook it for the Byzantines is supported by a number of 14th- to 16th-century maps of the area. Londina, Susaco, and Vagropolis are shown on an Italian portolan atlas of 1553 in the area around the Kerch Strait (a.k.a. the Cimmerian Bosporus), which leads into the Sea of Azov.

Susaco, a.k.a. Porto di Susacho, is the earliest of five English-related place names that show up on portolans from the 14th to the 16th century. It could refer to “Saxons,” or even to “Sussex.”

On more detailed charts from the 15th and 16th century, Londina is shown close by Susaco. It is possible this reference to London, perhaps originally applied to a coastal settlement, was later transferred to the river next to it. Hence numerous references to Flumen Londina (the Londina river).

Extract from a Black Sea portolan map from 1553 by Battista Agnese, showing the area and some of the place names of New England.

Both places are located east of the Kerch Strait, while two other “English” place names are to its west, on the Crimean peninsula itself: Varangolimen and Vagropoli, respectively translatable as “Port of the Varangians” and “City of the Varangians.” A third related toponym, Varangido Agaria, was placed near the mouth of the Don, on the Sea of Azov (itself labelled the Warang Sea on a Syrian map of c. 1150).

These must be the English Varangians, some academics argue, and their territory thus would have stretched from the southern tip of the Crimean peninsula via the southern shore of the Sea of Azov to east of the Kerch Strait.

Backing up that theory is a mid-13th-century report by Franciscan friars, speaking of a Terra Saxoni (“Land of the Saxons”), dotted with fortified cities and inhabited by Christians (as opposed to pagans or Muslims). The story of how they repelled a Tartar invasion suggests they were a formidable fighting force:

“When we were there we were told that the Tartars besieged a certain city of these Saxi and tried to subdue it. The inhabitants, however, made engines to match those of the Tartars, all of which they broke, and the Tartars were not able to get near the city to fight owing to these engines and missiles.”

“At last they made an underground passage and bursting forth into the city they tried to set fire to it, while others fought, but the inhabitants posted a group to put out the fire, and the rest fought valiantly with those who had penetrated into the city and, killing many of them and wounding others, they forced them to retire to their own army. The Tartars, realizing that they could do nothing against them and that many of their men were dying, withdrew from the city.”

This would support the theory that fighting was the main industry of these Anglo-Varangians, regularly supplying the emperor’s bodyguard with fresh fighters.

Very little else is known of this New England on the Black Sea, including when and how it ended. It is likely, however, that it eventually succumbed to another invasion of the Tartars, who would go on to found a Khanate in Crimea, and constitute the majority of the population on the peninsula — up until Joseph Stalin’s deportation of the entire Crimean Tatar nation to Central Asia in 1944.

The Tatars were allowed to return from 1967. At the census of 2001, they constituted 12 percent of the population, with Ukrainians making up 24.5 percent and Russians providing a majority of 58.5 percent.

The remaining 5 percent was made up of more than a dozen more ethnicities, hinting at Crimea’s colorful history. But among the Greeks and Koreans, Germans and Chuvash, Roma and Jews: not a trace of the New Englanders of old.

Many thanks to Fred de Vries, who saw the map on historian Dr. Caitlin R. Green’s website. Black Sea portolan map retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Strange Maps #715

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

[1] Mimicking the originals, New England is (mainly) to the south of New Scotland — Canada’s province of Nova Scotia. There used to be a New Ireland in between: a British colony set up after the American Revolution and re-occupied in the War of 1812, but returned to the Americans both times. The area now is part of the U.S. state of Maine. There is also a new New Ireland, but far away: an island in the Bismarck Archipelago, part of Papua New Guinea.

[2] The Ecclesiastical History (ca. 1140)by Orderic Vitalis mentions that it was “Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, had rebelled against the emperor [Alexius] in support of Michael, whom the Greeks had driven from the throne. So the Greeks welcomed the English exiles, who went into battle against the Normans — too powerful for the Greeks alone.”

[3] Siward is a likelier name than Stanardus for a mid-11th-century Saxon nobleman.

[4] Founded in 988 by Basil II, the Varangian Guard served as the emperor’s personal bodyguard. It was initially recruited among Varangians (the Slavic and Greek term for the Vikings who had settled in what later would become Russia and Ukraine), but also employed Northmen straight from Scandinavia. The Varangians were famous for their loyalty to the emperor, a quality enhanced by their detachment from Byzantine politics.

One of the most famous Varangians was Harald Hardrada, who became king of Norway and fell in battle at Stamford Bridge in 1066. His failed invasion of England contributed to the success, a few weeks later, of William’s conquest. And that in turn led to the emigration that swelled the ranks of the Varangians with Anglo-Saxons. Some reports suggest that after 1261, when the Palaeologos dynasty recaptured the throne, the Guard was composed entirely of Englishmen. These Anglo-Varangians had their own church in Constantinople, dedicated to St. Nicholas and St. Augustine of Canterbury (today often identified with the Bogdan Saray church, the ruins of which are enclosed by a tire shop).

The Varangian Guard was last mentioned in 1259. As late as 1400, there were still people in the city self-identifying as “Varangians” — although probably no longer resembling the “axe-bearing barbarians” of a few centuries earlier. The Varangians in Constantinople eventually blended in to the Greek mainstream.