Ask Ethan: Why will the Milky Way and Andromeda collide?

- Although they’re currently separated by 2.5 million light-years, the Milky Way and Andromeda are heading toward each other, and will eventually merge 4-to-7 billion years from now.

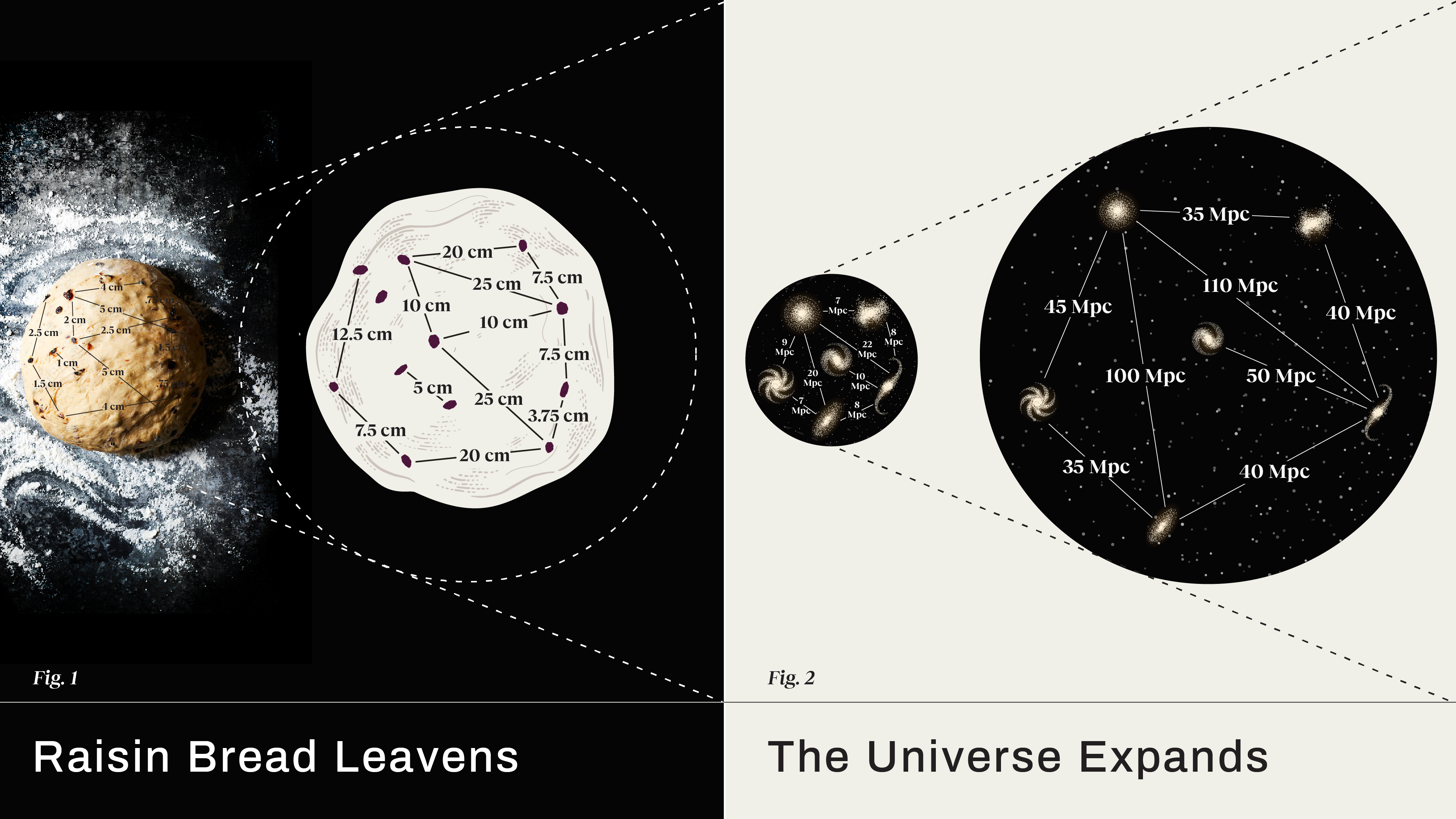

- Overall, not only is the entire Universe expanding, with galaxies spreading out and getting farther apart over time, but the expansion is accelerating, meaning galaxies are speeding up in their recession from each other.

- How can we reconcile these two simultaneously true facts? If the Universe is not just expanding, but accelerating, then how are galaxy mergers still occurring? Let’s unpack the answer.

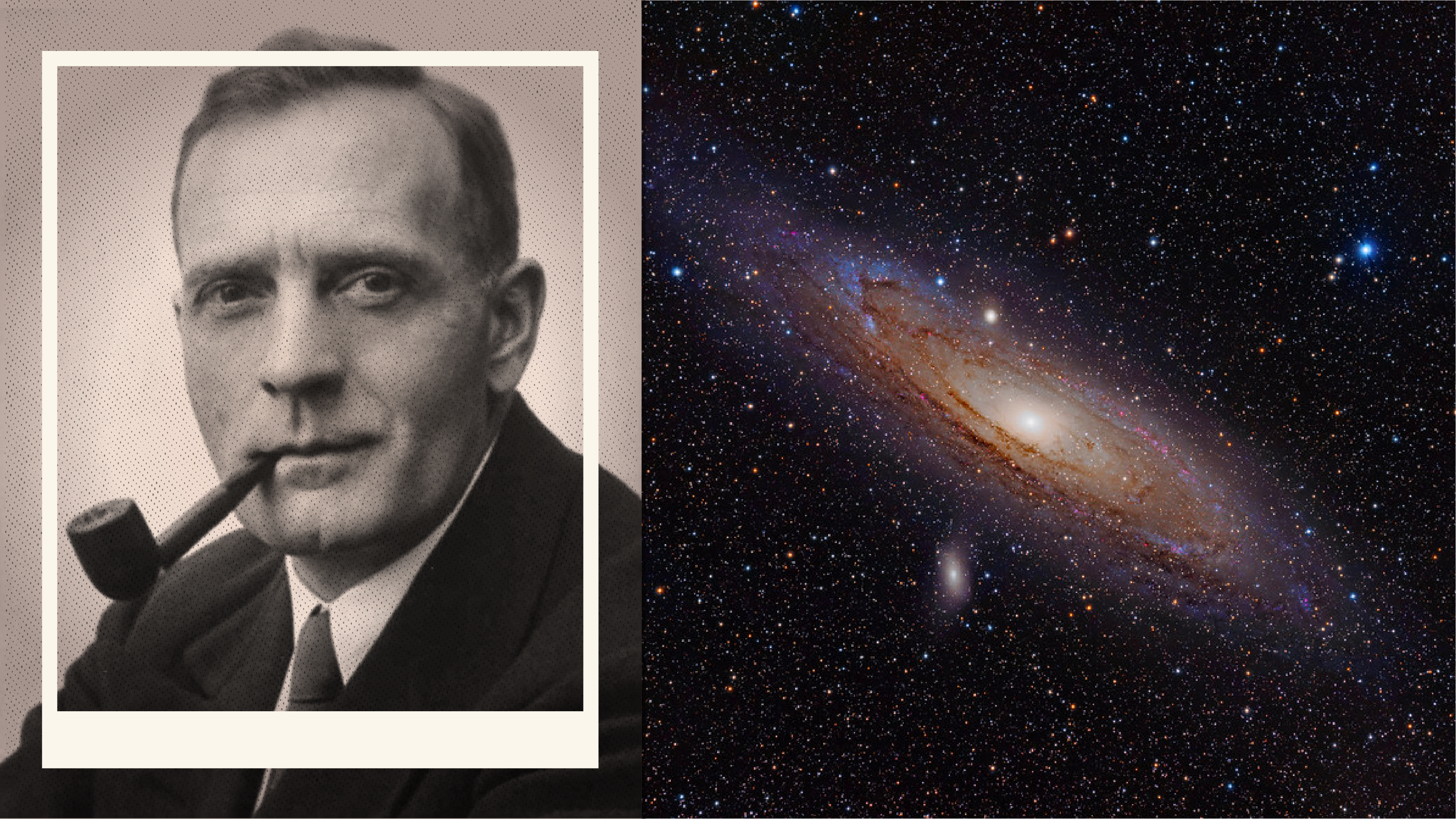

Of all the galaxies in the Universe that lie beyond the Milky Way, none looms larger than our “big sister” in the Local Group: Andromeda. Andromeda has more stars, more mass, and a larger physical extent than the Milky Way in all three dimensions. It spans a larger angular extent in our sky than six full Moons all lined up next to one another, and despite its location some 2.5 million light-years away from us, it’s actually moving in our direction, setting up a collision that should happen 4 billion years in our cosmic future. Another 3 billion years later, the greatest galactic merger in our Local Group’s history will be complete, leaving just one behemoth of a galaxy at its core: Milkdromeda.

But why is this happening? After all, not only is the Universe expanding, but the expansion of the Universe is accelerating, too! How could these two seemingly paradoxical points both be true: the expanding Universe is accelerating, but Andromeda is heading toward us and is destined for a collision-and-merger with us? That’s what Robert Asselta wants to know, writing in to inquire:

“If the universe is expanding and galaxies are spreading apart from each other, then why/how is Andromeda expected to collide with the Milky Way a few billion years from now?”

It’s a very smart question to ask, and the answer isn’t necessarily obvious. But if we go through the details, a clear answer emerges. Let’s find out!

The cosmic race

Ever since the dawn of the hot Big Bang, the Universe has been doing two things relentlessly. On the one hand, the Universe has been expanding, with the rate of expansion determined — at any particular moment in time — by the overall energy density of space, on average. Energy density includes energy in the form of:

- normal matter,

- dark matter,

- radiation (like photons),

- neutrinos,

- dark energy,

as well as anything else that might possibly exist, from exotic species of energy to topological defects to spatial curvature to anything present in extra dimensions. If you can calculate the total energy density due to all sources that contribute, plus the effects of spatial curvature, plus any effects due to a cosmological constant, you’ll know the expansion rate of the Universe at any moment in time.

But on the other hand, the Universe, even as it expands, also gravitates, with all forms of energy not just curving the local vicinity of the space they occupy, but affecting the overall expansion rate of the Universe. Recognizing this relationship between the different forms of energy present and the overall behavior of the Universe was first achieved in 1922, with the work of Alexander Friedmann in the context of Einstein’s General Relativity. Although this work is more than a century old, Friedmann discovered all three of the major possibilities that would be expected to occur.

Our Universe’s overall fate

On the largest of cosmic scales, the Universe behaves as though it’s a race between these two phenomena:

- the initial expansion rate that it began with at the start of the hot Big Bang,

- and the gravitational effects of all the various forms of energy that exist within that Universe.

The Universe is a race between these two effects, and the onset of the hot Big Bang is the “starting gun” between the only two competitors in this cosmic race. As Friedmann understood it, there would be three possible outcomes.

- The initial expansion could be too great for the amount of “stuff,” like matter and radiation, that are present in the Universe. In this case, the expansion would win, and although the effects of gravitation would slow the expansion down, the expansion rate would always remain positive, and the Universe would dilute, becoming emptier and emptier, with no end.

- Alternatively, there could be too much gravitating “stuff” in the Universe for the expansion rate to keep up. Gravitation wouldn’t just slow the expansion rate, but after enough time, it would grind the expansion to a halt. But with all that energetic “stuff” still in it, gravitation would continue, and the Universe would now contract. This reversal of expansion, contraction, would eventually lead to a Big Crunch.

- Or, just like Goldilocks and the three bowls of porridge, the three chairs, and the three beds, it’s possible that the Universe is “juuuuuust right,” and the expansion rate and gravitation perfectly balance. The Universe expands, but gravitation slows it: so that it approaches, but never quite reaches, zero. If one more atom were present, it might recollapse, but instead, it forever remains expanding, just by the tiniest amount.

Perhaps the only fault you can find with Friedmann’s analysis, even looking back more than 100 years later, is that he failed to anticipate that one of the categories of “stuff” that would be in the Universe would be a form of dark energy. As it turned out, the Universe really did look like it was on that Goldilocks path for about the first ~7 billion years of cosmic history: with the expansion rate dropping and dropping as gravitation slowed it down. It looked, if you had lived back then and been well-versed in the intricacies of modern physical cosmology, exactly like that “just right” case we outlined above.

But when the matter (both normal and dark) and radiation (and neutrinos) diluted past a certain point, a new effect began to appear: what we call dark energy today. This form of energy behaves as though it’s inherent to the fabric of space itself, so as the Universe continues to expand, it doesn’t dilute the way matter or radiation dilute; even as the volume of the Universe expands, its energy density remains constant.

This changes the fate of the Universe from the third option that Friedmann anticipated — the Goldilocks case — into an extreme version of the first option (the “expands forever” case): where not only does the Universe become emptier and emptier as time goes on, but distant galaxies, as they recede from one another, appear to recede at increasingly faster and faster speeds.

The global fate of the Universe

If you start here in the Milky Way and look at a distant, receding galaxy from us, you’ll find that its light is redshifted: that its wavelength has been stretched by the expanding Universe. As time continues to march forward, you could keep on monitoring the light from that galaxy, and see how it was changing. Would the amount its light was stretched by:

- increase,

- decrease,

- or remain the same,

as it continues to recede but also as the rate of expansion continues to evolve?

If you were watching that galaxy for the first 7.8 billion years of our cosmic history, you would’ve seen that “stretching amount” decrease, corresponding to that galaxy slowing down in its recession from our perspective. If you watched that galaxy when the Universe was precisely 7.8 billion years old, you would’ve seen that “stretching amount” remain the same, corresponding to that galaxy “coasting” in its recession, or continuing to recede at the same speed. And if you watched that galaxy over the most recent 6 billion years of cosmic history, you’d see the “stretching amount” of its light increase with time, implying that it was receding faster-and-faster.

That’s what we mean when we state “the expansion of the Universe is accelerating,” that for the past 6 billion years, any distant object we’ve looked at appears to recede ever faster and faster as time goes on. This is still the case today.

But what about smaller cosmic scales?

The story we’ve just told about cosmic expansion is strictly true, but it technically only applies to the overall Universe as a whole. The reason that’s the case is because there’s an assumption that went into the Einstein Field Equations — the equations that govern General Relativity — that allow us to make the simplifying assumption that Friedmann himself made back in 1922: that all forms of matter and energy are equally and uniformly distributed throughout the Universe. This is valid on the largest of cosmic scales and, for a typical region of the Universe, it’s valid on average.

But the Universe isn’t actually uniform everywhere.

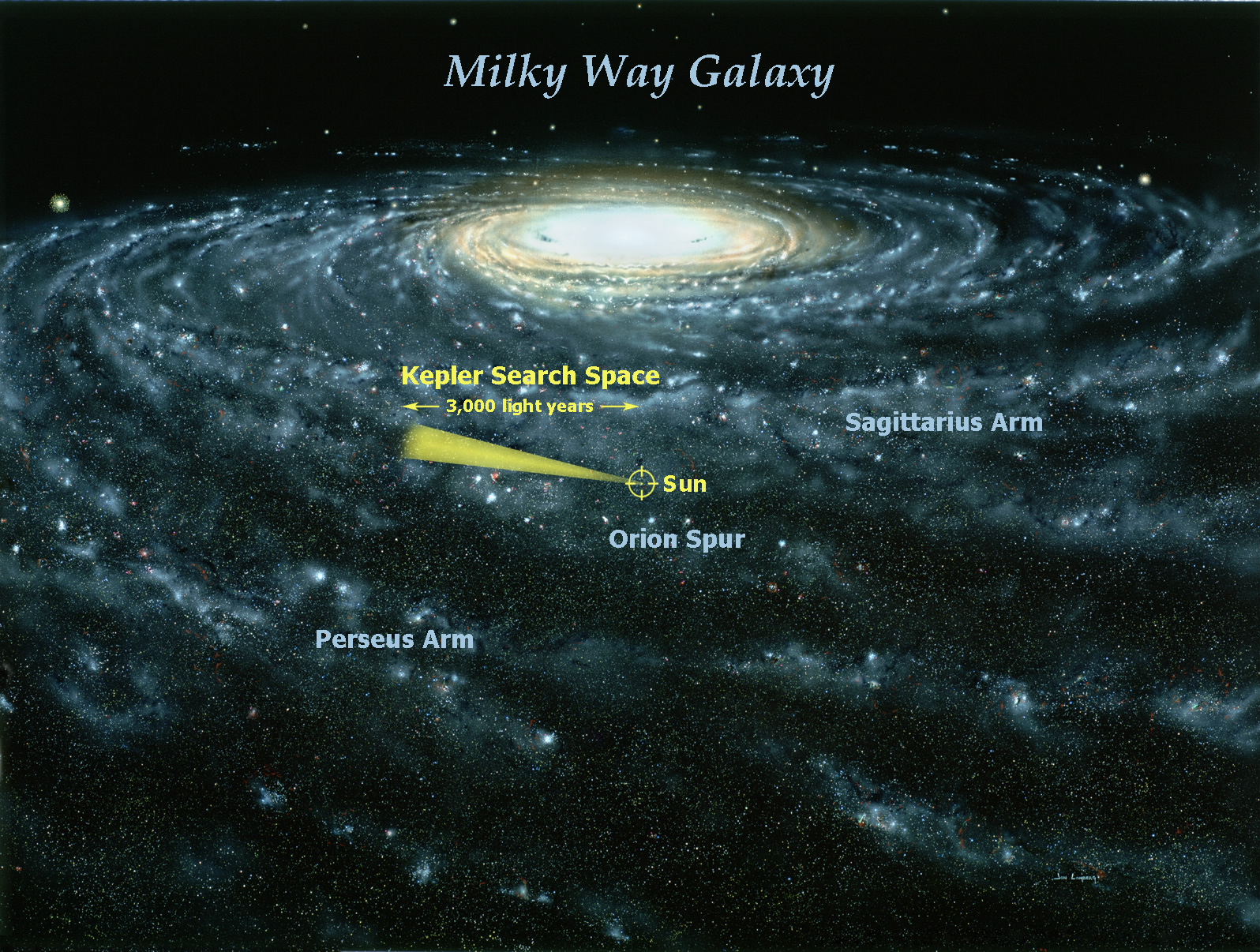

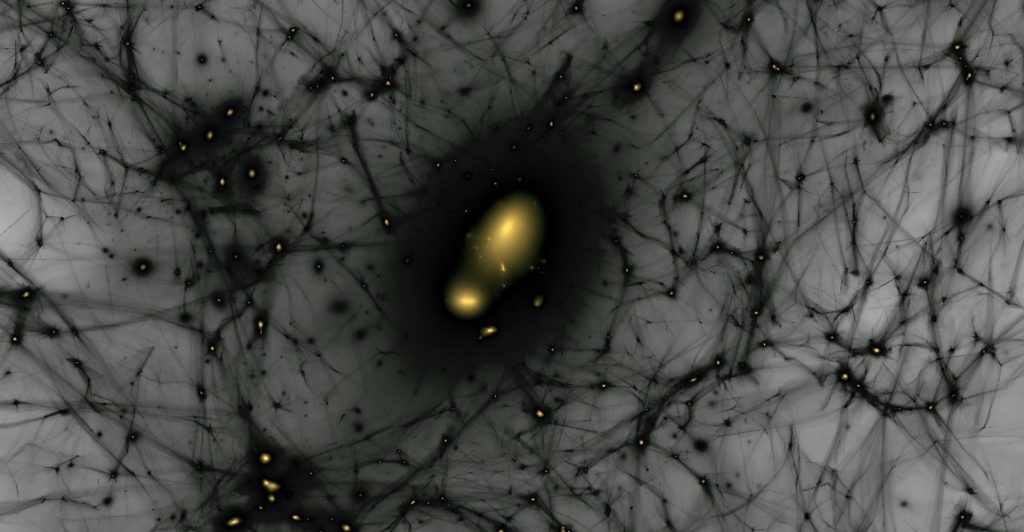

Instead, the Universe is filled with structure: galaxies, groups of galaxies, rich clusters of galaxies, and vast cosmic voids separating them. When we map it out in sufficient detail, we find a web-like network of structure in our Universe, where galaxies form along strands of that network and — more richly — at the nexus, or intersection, of those various strands. Matter gets preferentially attracted into these overdense regions, which causes it to flee the “in-between” regions, creating vast cosmic voids, with the difference between structure-rich and structure-poor regions growing more severe as time goes on.

The reason for this goes all the way back to the hot Big Bang itself. It turns out that sure, on average, the Universe is filled with the same amount of all forms of energy, including normal matter and dark matter, everywhere. But the truth is that the Universe was born seeded with tiny imperfections: overdense and underdense regions, at the level of just a few parts per 100,000 everywhere.

- Where you have an overdense region, the more successful you are at attracting more and more matter into you, and the more likely you are to grow to become some sort of massive structure: a star cluster, galaxy, group of galaxies, or even a rich cluster of galaxies, depending on the magnitude and physical extent/size of your overdensity.

- Where you have an underdense region, the more likely you are to give up your matter to a nearby dense region, and to expand and dilute into a diffuse cosmic void.

In reality, the Universe is filled with both types of regions on all cosmic scales, and those regions grow and shrink according to the laws of gravity, the expansion of the Universe, and whatever happens to be going on around them.

Who wins?

The only reason we have any structure at all in the Universe — things like star clusters, galaxies, galaxy groups, and galaxy clusters — is because there are regions, locally, where enough matter has accumulated together for gravitation to win: to “win” so thoroughly that it can indeed overcome the expansion of the Universe.

The way this occurs has been studied in detail by the branch of science known as physical cosmology, which deals, in part, with the formation of large-scale structure in the Universe. In the early stages of the Universe, overdense regions only grow slowly relative to the cosmic average.

- By the time 1 million years have passed since the Big Bang, the densest regions are only about ~0.1% denser than the average density.

- By the time 10 million years have passed since the Big Bang, the densest regions may only have grown to be about ~10% denser than the average density.

- But after a few tens of millions of years, the very densest regions have now reached a critical point: where they’re about ~68% denser than the average density.

Once that point is reached, something very important happens: gravitation is now important enough that the expansion of the Universe starts losing to gravity in this region of the Universe. Gravitational collapse becomes all but inevitable, and a bound structure will form.

This occurs on small cosmic scales first, leading to star clusters: likely when the Universe is only between 100-200 million years old. Then it occurs on larger scales: with star clusters merging together and larger cosmic scales collapsing to form galaxies: likely when the Universe is a few hundred million years old. Then, still larger scales collapse, leading to the first galactic groups and the earliest proto-clusters of galaxies: within the first ~1 billion years of our cosmic history. And finally, you only get mature galaxy clusters after a few billion years have passed, owing to the enormous cosmic scales (and the limit set by the speed of light) at play.

The reason Andromeda and the Milky Way will someday merge together — and yes, they really are on a collision course — is because way back in the early stages of the Universe, more than 10 billion years ago, we all got gravitationally drawn in to become part of the same gravitationally bound structure: our Local Group. Eventually, given enough time, all of the galaxies within our Local Group will collide and merge together, although this process should take several tens of billions of years, multiple times the present age of the Universe, to complete. The Milky Way and Andromeda should approach each other for the next 4 billion years, begin merging at that time, and complete their merger after about another 3 billion years: a total of 7 billion years from now.

The only reason that merger will occur, however, is because the Milky Way and Andromeda are already part of the same gravitationally bound structure, the Local Group, that became dense enough early enough on to overcome the expansion of the Universe. Although the Universe began accelerating 6 billion years ago, there were still enough dense, growing regions that were gravitationally attracting one another and the matter around them that structures had until about 4.5 billion years ago — around the same time that the Sun, Earth, and Solar System were forming — to become gravitationally bound.

Today, the situation has already been decided: if you’re part of a gravitationally bound structure, you’ll wind up bound to it; if you haven’t yet gotten there, you never will be. Although the Milky Way, Andromeda, and all of the remaining Local Group galaxies will eventually merge together, our Local Group itself will never merge with any of the galaxies, galaxy groups, or galaxy clusters found outside of it. Our Universe has become like a sea of islands, where each island remains as a solid mass, but where separate islands eternally receding from one another in the vast, accelerating, expanding cosmic ocean.

The only reason the Milky Way and Andromeda will merge is because they became gravitationally bound to one another before dark energy took over. Galaxies will still merge for tens of billions of years to come, but only in those groups and clusters that became gravitationally bound billions of years ago.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!