Political realities do not change scientific ones

- For many decades now, scientists have had to combat misinformation from political and corporate forces about the scientific reality of many aspects of life and human activity on Earth.

- From the health hazards of smoking to the realities of a warming planet to the safety and efficacy of vaccines to fluoridated drinking water and much more, science gets politicized whenever it threatens someone’s bottom line.

- Many scientists, science communicators, and science journalists are reacting in an unprofessional and unsound manner to the current political climate. The correct course of action is simple: just tell the actual scientific truth.

As the latest election cycle in the USA winds down and people across the country and world begin to reckon with the results — and their consequences — you could be forgiven for thinking that science is in a lot of trouble. Confidence in science and scientists has waned in recent years, particularly among those with right-wing-leaning politics, and the political leanings of scientists, fairly evenly split during most of the 20th century, is now being put under the spotlight as a vast majority of practicing scientists themselves have left-wing-leaning personal politics. Many contentious issues today, including:

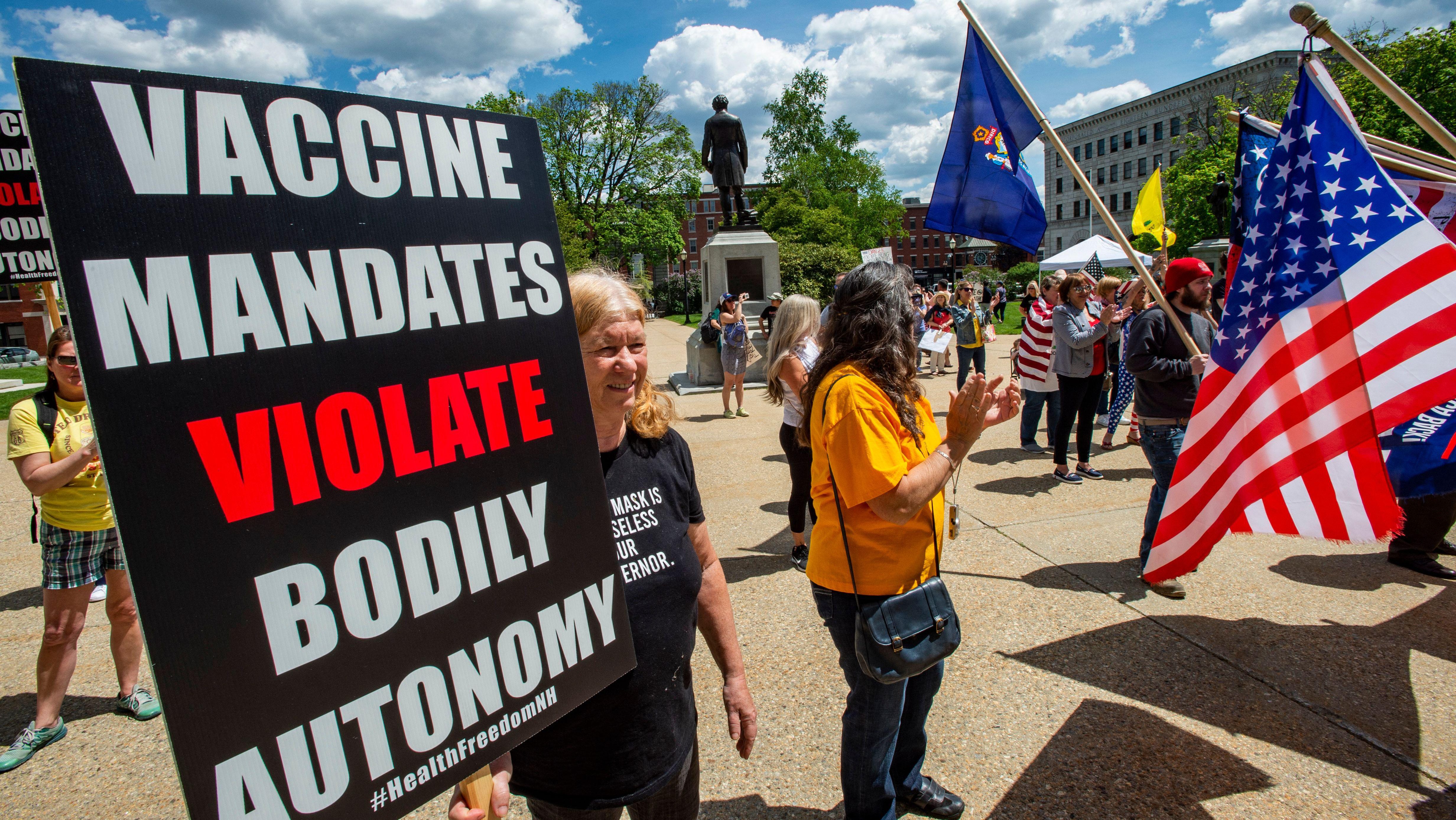

- the safety and efficacy of vaccines,

- the benefits and risks of fluoridated drinking water,

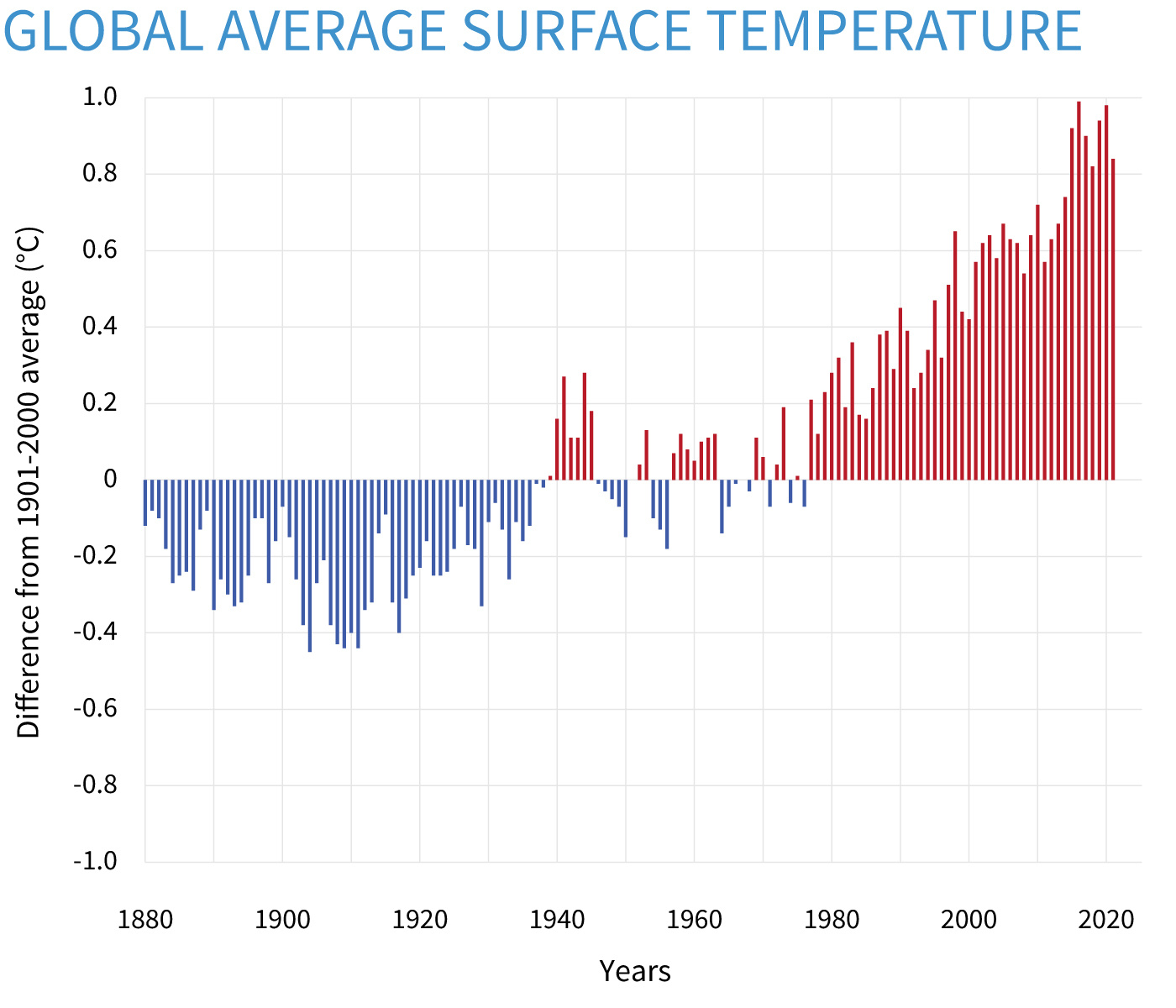

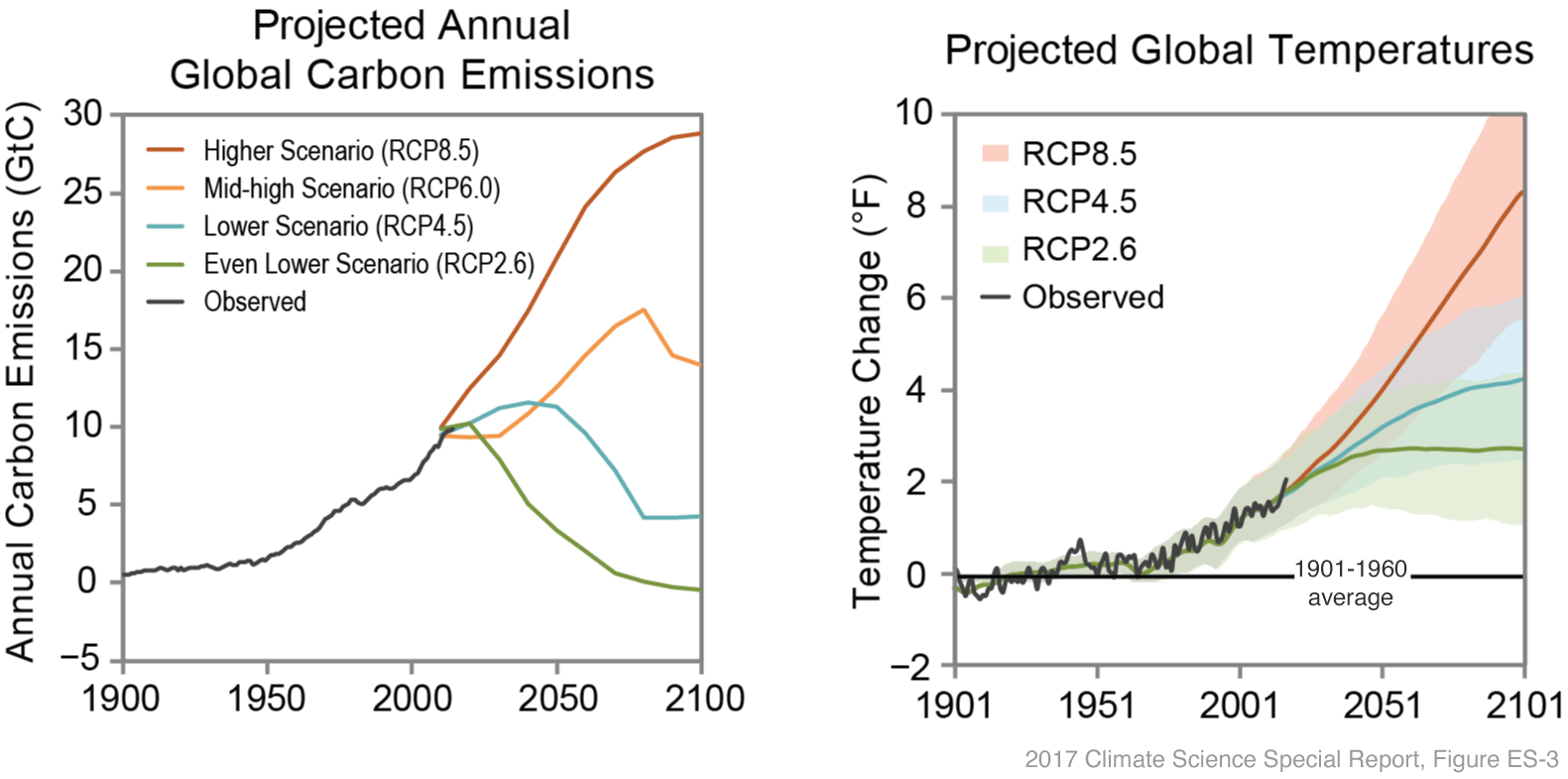

- the realities of a warming planet,

- plus the societal benefits of a healthy and robust investment in basic, fundamental science,

are going to have policies made about them that will be subject to political whims, rather than with policy driven by the actual scientific merits underlying these issues.

What should scientists do about this?

The answer is as simple as it is straightforward: Tell the unbiased, comprehensive scientific truth about whatever issue it is that’s in play. There’s no place for exaggeration, but there’s also no need to let your political views — or your fears about how factual information is likely to be weaponized by those with opposing political views — prevent you from stating truthful facts about reality in a straightforward, accessible fashion. Whether we get the policies that benefit society or not is not up to science, but up to our elected government. All we can do is correctly inform the world, including by correcting incorrect information, wherever it appears (including when it appears from government officials).

Here’s how to make sure you’re doing it responsibly.

Step 1: Recognize where people actually are in terms of what they believe to be true.

This seems like such a basic step that it might feel insulting to even mention it. Nevertheless, this is one of the most important aspects of communication of any type: to ensure that you’re meeting your target audience where they are, rather than where you wish they were at the start. If you don’t engage people at a starting point where you can draw them in, you’re not going to be communicating with them at all. And if you can’t effectively communicate with someone — i.e., if you’ve chosen to communicate in such a way that they’re not going to open their ears to you at all — it’s as though you haven’t engaged in any sort of communication at all.

You might balk at this, and ask something like, “If someone is misinformed, or has been captured by the spell of someone with a vested interest in misinforming them, then why should I have to engage with that misinformation at all?” The answer is simple: because, as a scientist and/or a science communicator, you care about answering the question of, “What is true/real?” And if you want to answer that question effectively, you need to go into the act of communicating by at the very least understanding what your audience perceives to be the truth/reality ahead of time. If you can’t have a respectful discussion with them, even if their initial thoughts are diametrically opposed to the actual reality, you’re automatically excluding them as your potential audience.

Step 2: Give as appropriate of a “background” as necessary before diving into any new results.

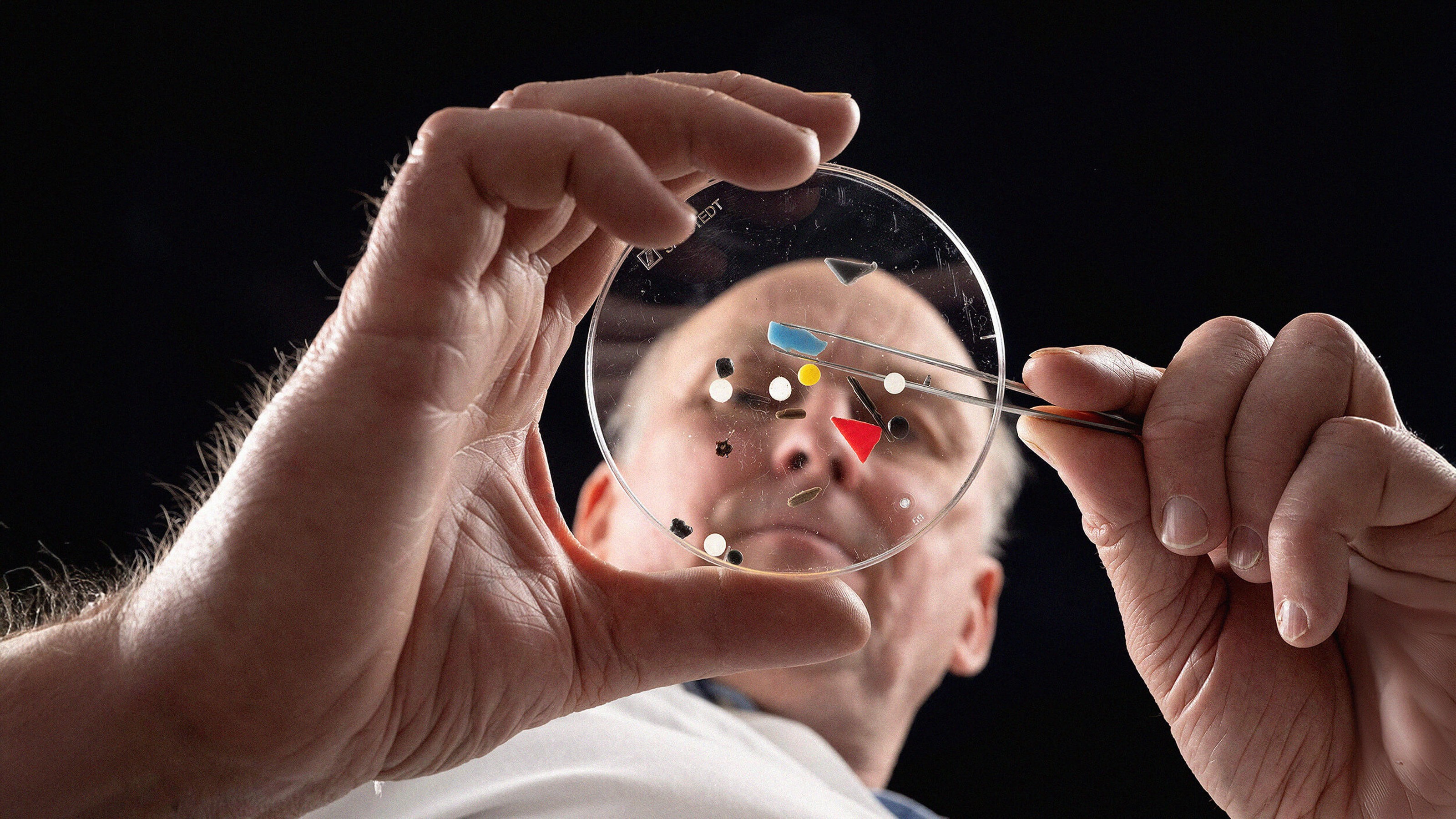

This is, for many scientists, the most “boring” approach, and yet it’s the most essential component of it. There is an enormous amount of misinformation out there, and many people believe these untruths to be real. How do you combat it? Whether it’s about:

- the Earth being flat,

- fluoridated drinking water posing significant health risks and dubious health benefits,

- vaccines being unsafe, ineffective, and potentially dangerous to developing bodies,

- the question of whether the climate and temperature of Earth is changing and why,

- or the safety of GMOs for human consumption,

you have to recognize that whatever “new” information you want to share with the world about these issues, as important as it may be, has to be communicated to an audience that has an enormous variety of opinions about these issues to start with.

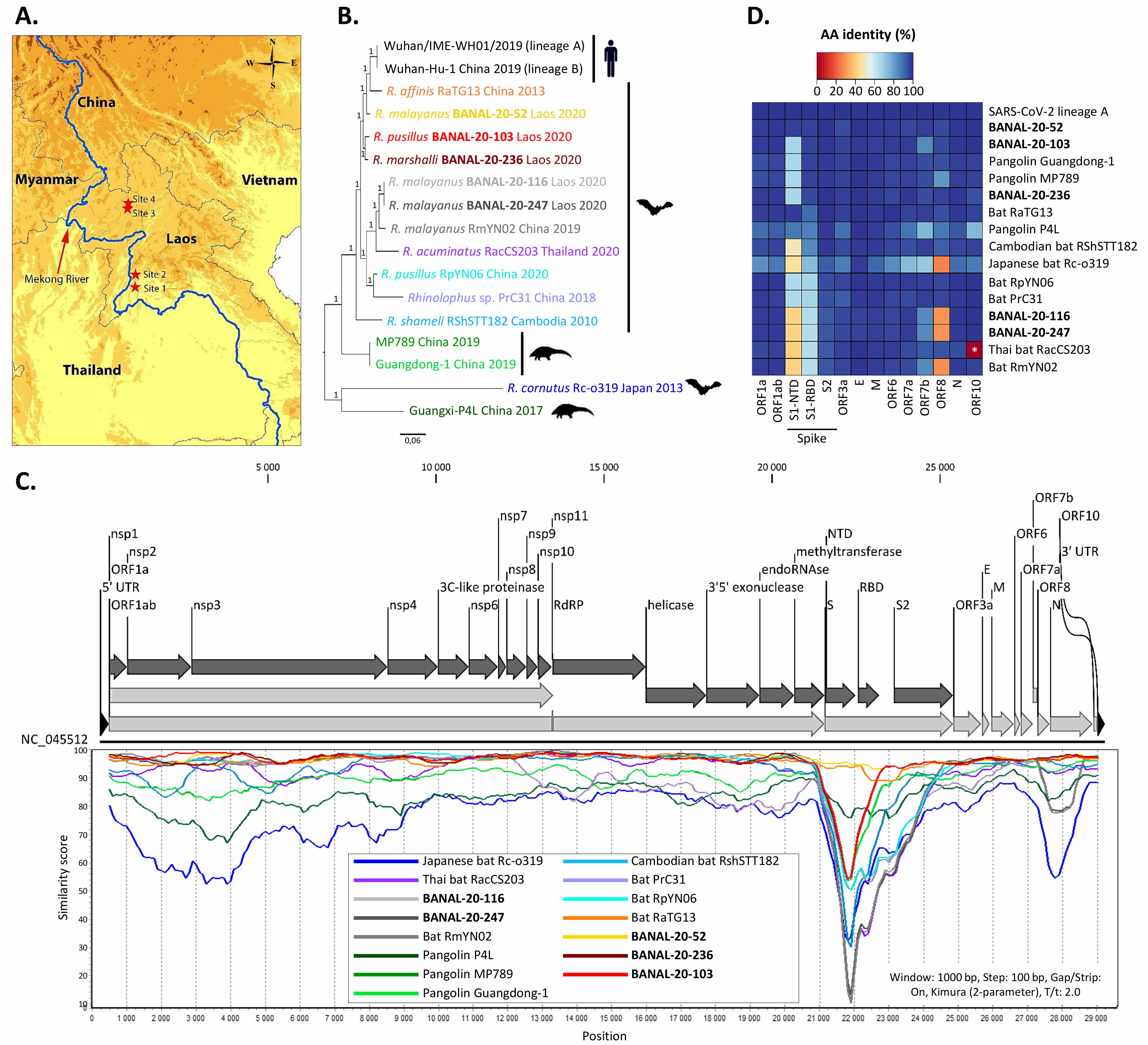

For example, if you want to have a conversation about public health and pandemic prevention, you have to understand that the conversations virologists and disease ecologists are having among themselves — the importance of identifying potential pathogens in advance, studying how to fight them and how to trigger the human body’s immune response to effectively combat them, and gathering evidence to understand where they arise and how they spread to humans, etc. — are very different than the conversations politicians and media personalities are having about it.

What should scientists be doing, for example, when there’s a very popular narrative that:

- the pandemic didn’t begin from a zoonotic event at a wet market in China, but rather was created in a Chinese lab by unethical researchers who hid their research,

- the worst casualty of the pandemic wasn’t the millions upon millions of deaths or the hundreds of millions of cases of long COVID, but rather the psychological damage to children caused by lockdowns,

- and that scientists only care about funding for their own pet research projects, not for the health and well-being of society at large.

The answer is actually simple: be straightforward, clear, and direct about not only what is real about the thing you, as a scientist, want to talk about, but also about the reality of any/all of the issues that other people have on their minds.

You might feel like it’s beating a dead horse, or responding to an argument that’s been debunked hundreds of times over, but that’s all the more reason to engage in an honest and truthful fashion. There is an alternative theory for the origin of the pandemic out there, and the key question to ask and examine is, “What does the evidence indicate?” which gives a clearly preferred answer on scientific grounds. Deaths and cases of long COVID have been quantified (and hold important lessons for the efficacy of vaccines, too), but the psychological impacts of the pandemic, including lockdowns, should be discussed and quantified as well; these are real and important to the lives of many. And admit that scientists do care about funding, but be transparent about how the scientific enterprise makes decisions about that funding.

In the end, a more complete, comprehensive picture shines a light that makes it much, much harder for misinformation — which thrives in the shadows — to overcome correct information.

Step 3: Be clear and persistent about the benefits of public health and publicly funded science.

How many diseases have been prevented because of childhood vaccines? How many deaths have been averted, how many life-altering injuries have been avoided, by this public health intervention? How many fewer cavities are there in children, especially poor/lower-income children, in communities that have water fluoridation programs versus those that don’t? How much does our society benefit from money that gets invested into basic scientific research: things with no immediate technological applications?

All of these questions not only can be studied from a scientific point of view, but have been studied at great length. You can learn that around 3.5-5 million lives are saved annually by vaccination campaigns alone. You can learn that about 10% of all necessary dental expenses, or about $2.5 billion dollars worth, would be prevented by bringing water fluoridation to currently unfluoridated communities. And NASA, whose fiscal year budget in 2023 was about $25.4 billion dollars, resulted in a $75.6 billion boost to the economy in that same year: a $3 return in economic activity for every $1 spent on it. (And that’s in addition to new technology reports, patent applications and issuances, and new software that results from spinoffs: public products that are developed with NASA technology.)

These benefits are reaped and shared by us all, and anyone who claims otherwise should be met with truthful responses that show exactly what is real instead.

Step 4: Keep communicating the importance of consensus within the community.

A lot of people have attempted to smear the word “consensus” as something that’s thrown around to shut down legitimate scientific debate over a contentious issue. Those of us who are practicing scientists know that exactly the opposite is true; consensus is not something that is ever obtained unless the robust suite of scientific evidence supporting such a position is overwhelming.

In reality, scientists never reach a consensus lightly on any issue; if the evidence isn’t crystal clear in support of one particular cause-and-effect scenario, the community will be split. We are completely certain, insofar as science can ever be certain about anything, that:

- the Earth is a round spheroid,

- humanity did indeed land on the Moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s,

- general relativity is our best theory of gravity, having passed every test thrown its way,

- and that the hot Big Bang is the best story we have as far as explaining our cosmic origins goes.

This is not because there aren’t alternative ideas out there; there very much are. It’s because the evidence in support of these particular ideas — and which is not consistent with other, alternative ideas — is undeniable on scientific grounds. That’s how scientists decide matters: on their merits, not on any other grounds.

Scientists are often unfairly accused of groupthink, of following the herd, or of being wholly unimaginative or closed-minded when it comes to new ideas. But that’s not reflective of reality at all; in fact, it’s antithetical to it. In fact, much of what you’ll read if you follow science news are loud proclamations that our current understanding of reality is wrong, and that some new, revolutionary idea is right instead. That’s not accurate or true, of course; most of these stories are simply highlighting one piece of research that challenges the consensus model of the day. These challenges are important and ubiquitous, because they’re part of how science advances: by revisiting our assumptions.

- We assume that dark matter and dark energy are correct models of reality because of their successes and how hard-to-impossible those successes are to reproduce without them.

- We assume that our fundamental picture of reality, with the Standard Model of elementary particles combined with general relativity for gravity, is successful everywhere because of how thoroughly it’s been tested, even though we doubt it’s our ultimate final theory of reality.

- We assume that a phase of cosmic inflation preceded and set up the initial conditions for the hot Big Bang, but not because of bias or groupthink, but because of the overwhelming evidence that supports it.

Consensus positions such as these only arise when the evidence is extraordinarily strong, such as against the lab leak origin idea for SARS-CoV-2 or in favor of human activity being the unprecedented driver of global warming and global climate change. Where the evidence is less strong, debate and uncertainty justifiably thrive.

Step 5: Do not “massage” the truth to make it more palatable to those who are resistant to its message.

One of the recommendations that misinformers often make ad nauseam is that scientists should get on board with contrarian viewpoints and to stop demonizing those who advocate for them. Whether you’re a public health agency that’s halted your COVID vaccine program because of safety concerns (an unscientific position that’s debunked at length here) or a community that’s afraid of fluoride’s perceived harms (even though those perceptions are contrary to reality), scientists are being pressured to be more friendly to these fundamentally anti-science positions.

Here’s the deal: you can be friendly to people, including to people who’ve succumbed to the allure of misinformation or an alternate reality, while still remaining firmly rooted in what is scientifically true.

People make decisions based on all sorts of reasons, not merely scientific ones alone. When I was a teenager, I met a young adult with an enormous set of scars up his arms and on his head that he received in a car accident where he was a passenger who wasn’t wearing a seat belt. He went through the front window and required over 200 stitches. Here’s the kicker: if he had been wearing a seat belt, his body would have been crushed in the front seat. He’s one of the low-percentage of people whose life was actually saved by not wearing a seat belt.

How could one convince him to follow the science and do what would lead to the best outcome more often than not?

The answer is simply: you can’t. It isn’t congruent with his experience, and people are going to make their own decisions based on their own experience, even if it’s ultimately not in their best interest. We can have compassion for people who feel and reason this way, while still being very clear about what the science says and what the consequences are for those who reject its recommendations. The scientific truth, whether one believes it to be true or not, remains unchanged.

Step 6: Recognize that people are free to choose a policy that doesn’t align with science’s best recommendations, and that even when they do, science (and its benefits) are still for them.

Let me ask you: when that same friend of mine, with the scars on his arms and head, got into a vehicle with me back when I was 14 years old, what do you think “his policy” was on whether I wore a seat belt or not?

Do you think he said, “If I don’t wear one you don’t wear one?” Do you think he said, “Your body, your choice?”

Well, maybe some people would say those things, but my friend didn’t. He told me to wear my seat belt, and that we weren’t going anywhere until I did. It may seem like inconsistent reasoning to you, but he recognized what the science showed and understood what the odds were, statistically, of me being in a safer situation because I was buckled up.

There will be plenty of people who will be zealot-like in their refusal or resistance to any or all health and safety policies recommended by scientists, a governmental body, or any other authority figure. There will also be powerful figures — political and apolitical, religious and secular, scientific and nonscientific — that people will appeal to when making their decisions instead of the best scientific (e.g., the consensus) position.

That doesn’t make them monsters. It makes them human. Be aware that if you demonize them, they’re not going to listen to you. If you instead make it clear that science, its recommendations, and its benefits are for everyone, them included (whether they appreciate it or not), you leave the door open for them to embrace it in whatever way they’re capable of whenever they so choose.

To be clear, there are no circumstances where a scientist should accept misinformation and disinformation as substitutes for actual, factual scientific information. The advances that science makes are dependent on improving or extending prior research, either confirming, revising, or refuting what our leading thoughts were prior to that research being conducted. There is no substitute for this; it is an essential element of a functioning society. Many have rejected the science of their day in favor of more politically favorable positions, and the result, whether from Lysenkoism in Soviet Russia, from deforestation on soil stability in Brazil, or from an inability to reckon with farming realities in 1990s North Korea, always shows one inescapable truth: the consequences of rejecting science always catch up with you eventually.

Whenever people are driven by fear, anger, or the desire for revenge, you can’t just expect them to put all of those feelings aside and instead to embrace something logically and dispassionately. That’s the reality that we’re facing today: a society that’s making decisions based on other factors beyond, “what’s best for me, individually, plus what’s best for all of us, collectively.” However, science itself not only isn’t driven by those factors, but those factors cannot enter into any legitimate scientific inquiry, otherwise your inquiry is biased from the start. As scientists in a democratic society, we must accept that science can inform, but it’s up to us (as voters) and those we elect (as representatives) to enact policy. Science can — and should — pass judgment on which policies are and aren’t scientifically sound and consistent with scientific reality. Beyond that, however, our job is to merely inform. The downstream political decisions themselves, on what science gets funded and what policies get enacted, are never going to be decided on scientific merits alone.