Don’t buy the hype on new “breakthrough” Alzheimer’s treatments

- Like beacons of light in the dark, two drugs have emerged over the past two years as the first “disease-modifying” treatments for Alzheimer’s disease.

- However, these drugs are expensive, complicated to administer, and can cause dangerous side effects. Most importantly, numerous researchers think the drugs’ benefits will be imperceptible to patients and their families.

- Rather than grasping for a nebulous medical solution, many experts say it’s better to focus on prevention. Roughly 40% of dementia cases could be delayed or prevented by addressing lifestyle and environmental factors.

The quest to find effective treatments for Alzheimer’s disease has historically been a lost cause — a field littered with failed drugs and dashed hopes. According to a recent systematic review, between 2003 and 2022, researchers tested 100 compounds against the devastating cognitive disease in phase II and III trials. Only two drugs made it through the rigorous gambit of pharmaceutical science. Their beneficial effects were too small to make a meaningful difference to patients.

Then, like beacons of light in the dark, two drugs emerged over the past two years from phase III clinical trials as the first “disease-modifying” treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. Eisai and Biogen’s lecanemab burst onto the scene first, with data suggesting that it slowed cognitive decline by 27%. Eli Lilly’s donanemab followed with more impressive results, slowing decline by 35%. Scientists and journalists used words like “breakthrough” and “revolutionary” to describe the findings. Both drugs were given to older adults in the very early stages of Alzheimer’s, in trials lasting 18 months.

Slowing Alzheimer’s

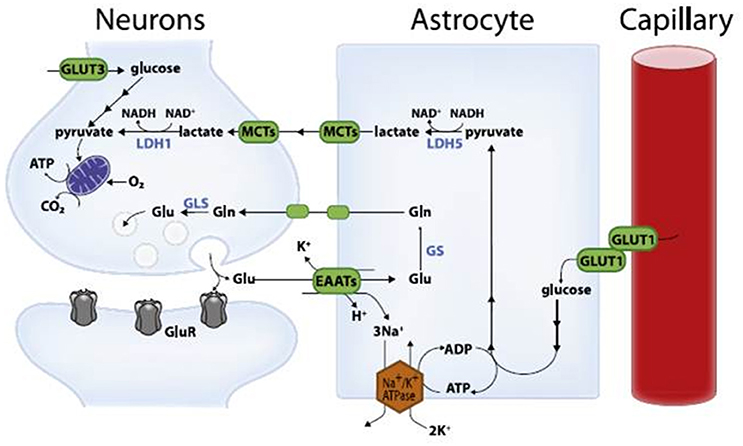

A “disease-modifying” treatment is one that delays, slows, or reverses the progression of a disease by targeting its underlying cause. Until lecanemab and donanemab, treatments for Alzheimer’s only lessened the debilitating symptoms: memory loss, paranoia, difficulty focusing, etc. These two drugs, however, slowed the disease’s progression while removing aggregated clumps of misfolded beta-amyloid proteins. Such plaques have long been theorized as a potential cause of Alzheimer’s as they are highly prevalent in three-quarters of sufferers’ brains, first developing in areas that deal with memory and other cognitive functions. Just over two-thirds of participants receiving lecanemab actually had their brains effectively cleared of amyloid plaques. More than 80% of those given donanemab did.

But this is where the drugs start to lose their sheen. Lecanemab and donanemab removed the amyloid plaques, yet the Alzheimer’s patients in the trials continued to decline. (Remember, the drugs only slowed the disease. They didn’t stop it.) This suggests that beta-amyloid buildup is likely not the primary cause of Alzheimer’s, hinting that the drugs’ overall effectiveness will be limited over the long term.

Derek Lowe has worked on drug discovery for over three decades, including on candidate treatments for Alzheimer’s. He writes Science’s In The Pipeline blog covering the pharmaceutical industry.

“Amyloid is going to be — has to be — a part of the Alzheimer’s story, but it is not, cannot be a simple ‘Amyloid causes Alzheimer’s, stop the amyloid and stop the disease,'” he told Big Think.

Lowe is one of many commentators who has also noted that the drugs’ beneficial effects would likely be imperceptible to family and friends. Data from the trials back those dour opinions.

“Although the effect of the drug will be described as being about a third, it consists, on average, of a difference of about 3 points on a 144-point combined scale of thinking and daily activities,” Professor Paresh Malhotra, Head of the Division of Neurology at Imperial College London, said of donanemab.

What’s more, lecanemab only improved scores by 0.45 points on an 18-point scale assessing patients’ abilities to think, remember, and perform daily tasks.

“That’s a minimal difference, and people are unlikely to perceive any real alteration in cognitive functioning,” Alberto Espay, a professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, told KFF Health News.

At the same time, these potentially invisible benefits come with the risk of visible side effects. Both drugs caused users’ brains to shrink slightly. Moreover, as many as a quarter of participants suffered inflammation and brain bleeds, some severe. Three people in the donanemab trial actually died due to treatment-related side effects.

Steep costs, limited benefits

Then there are the time and costs associated with actually administering the drugs. Before taking one, prospective patients must receive a PET scan to look for amyloid plaques. They also must undergo genetic testing to confirm they don’t have specific genes that would make them more susceptible to side effects. Once they start the treatments, patients require regular injections — every two weeks for lecanemab and four weeks for donanemab — in a clinical setting. They also require frequent scans to watch for brain inflammation and bleeding.

All of this will take time and money. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) tabulated the annual costs for lecanemab, which is FDA-approved. They came to roughly $109,000 per patient per year. Included were the $26,500 list price, as well as the costs for actually administering the treatment. The ICER also convened a panel of 15 experts and asked them to assess the treatment’s value for the money. All 15 voted that the value was low.

Donanemab has yet to receive FDA approval but it should arrive this year. When it does, experts expect the value to be similarly unimpressive. Medicare and Medicaid patients will comprise most of the market for the new treatments for Alzheimer’s. So taxpayers and other beneficiaries will end up footing the sizable bill.

Hope amid few options

But should a cold cost-benefit analysis be the only way to analyze lecanemab and donanemab? In written comments to Big Think, Chuck Dinerstein, Medical Director at the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), presented a different perspective.

“While much has changed over the last few decades with respect to medicine’s tools, at some point, medical options are exhausted, and the physician can only offer one of our older tools: hope. The importance of hope should not be underestimated; for those of a scientific bent, consider hope like a placebo, which works 30% of the time.

These novel treatments undeniably constitute Alzheimer’s patients’ best source of hope in decades.

“Patients and families will be pushing very hard to get this drug, and they are not going to be objective when it comes to determining its value; maybe Mom has a few better days a month and can recognize you and chat for a few minutes,” Dinerstein added.

Roughly 6.5 million Americans suffer from Alzheimer’s dementia today, and that population is projected to double by 2050. You can bet that many of them and their family members will consider $100,000 a pittance if it means slowing the disease, even for just a few months.

Will there come a time when treatments for Alzheimer’s are clearly cost-effective? There are many who think that lecanemab and donanemab collectively represent a solid start down that path.

“The success of these drugs is likely to spawn and guide years of subsequent research,” Yale neurologist Steven Novella wrote at Science-Based Medicine.

But others aren’t so sure. Again, these drugs target beta-amyloid plaques and they were very good at clearing them. Yet the beneficial effects were comparatively paltry. Some researchers say we just have to get patients these drugs earlier and clear the plaques more quickly before they grow widespread.

“The hope is that very early treatment will slow progression enough that people will not live long enough to ever develop severe dementia,” Novella wrote. This may lead to screening for Alzheimer’s Disease in asymptomatic individuals, especially if there is a family history.”

Lowe is skeptical.

“That answer has been eroding as these trials have tried to catch people earlier and earlier in the disease progression. I honestly don’t know what else you’d do: give people the drugs before they’re diagnosed with Alzheimer’s? That’s not going to be possible,” he said.

And what if the primary cause of Alzheimer’s isn’t beta-amyloid?

“I think it’s quite possible that the plaque hypothesis is backward; that the plaques are a result of something that has already happened to affect the brain, not the cause of the disease,” Josh Bloom, Director of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Sciences at ACSH, told Big Think. “If this is true then it doesn’t much matter what antibody or drug is used to dissolve the plaques, it’s already too late. It would be like trying to treat a wound by getting rid of the scab.”

Other theorized causes of Alzheimer’s include tangles of another protein called tau or possibly a viral infection.

“Unfortunately, I am not optimistic about any drug or antibody putting much of a dent in this horrible disease. There is just too much that doesn’t make sense about what is really going on,” Bloom said.

Prevention vs. treatment

Rather than grasping for a nebulous medical solution, many experts say it’s better to focus on prevention. Roughly 40% of dementia cases could be delayed or prevented by addressing lifestyle and environmental factors, according to a report published in The Lancet. These factors include exposure to air pollution and excessive alcohol consumption.

Maintaining a healthy blood pressure might be the single best preventative measure. Researchers at Johns Hopkins have found that people using blood pressure medications lowered their risk by about one-third. Moreover, studies suggest that learning a second language could delay the onset of Alzheimer’s symptoms by five years on average.

While treatments for Alzheimer’s aren’t that effective, numerous preventative measures are.

Correction 3/19: An earlier version of this article stated that one-third of participants receiving lecanemab had their brains cleared of amyloid plaques. It is actually just over two-thirds.