Just one exo-Earth pixel can reveal continents, oceans, and more

- In the coming years and decades, several ambitious projects will reach completion, finally giving humanity the capability to image Earth-size planets at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars.

- Recent data suggests that there are around ~10 billion such planets within the Milky Way alone, and with each one being like a lottery ticket, it’s only a matter of time (and statistics) before we find one that’s potentially inhabited.

- Remarkably, even though these exo-Earths will appear as just one lonely pixel in our detectors, we can use that data to detect continents, oceans, icecaps, forests, deserts, and more. Here’s the fascinating science that’s just over the horizon.

Over the past 35 years, a tremendous transformation has occurred in astronomy. Back in 1990, there wasn’t a single planet known outside of our own Solar System. Exoplanets had been claimed previously, but all were found to be mere mirages: artifacts of false signals hiding in insufficiently precise data. Today, in 2025, we’re closing in on 6000 confirmed exoplanets, with the majority discovered either by transiting in front of their parent stars or by the planet’s gravitational effect causing the star to “wobble” in a detectable fashion. However, a third technique — direct imaging — has also successfully found exoplanets, so long as they’re bright enough and separated by a great enough distance from their parent star.

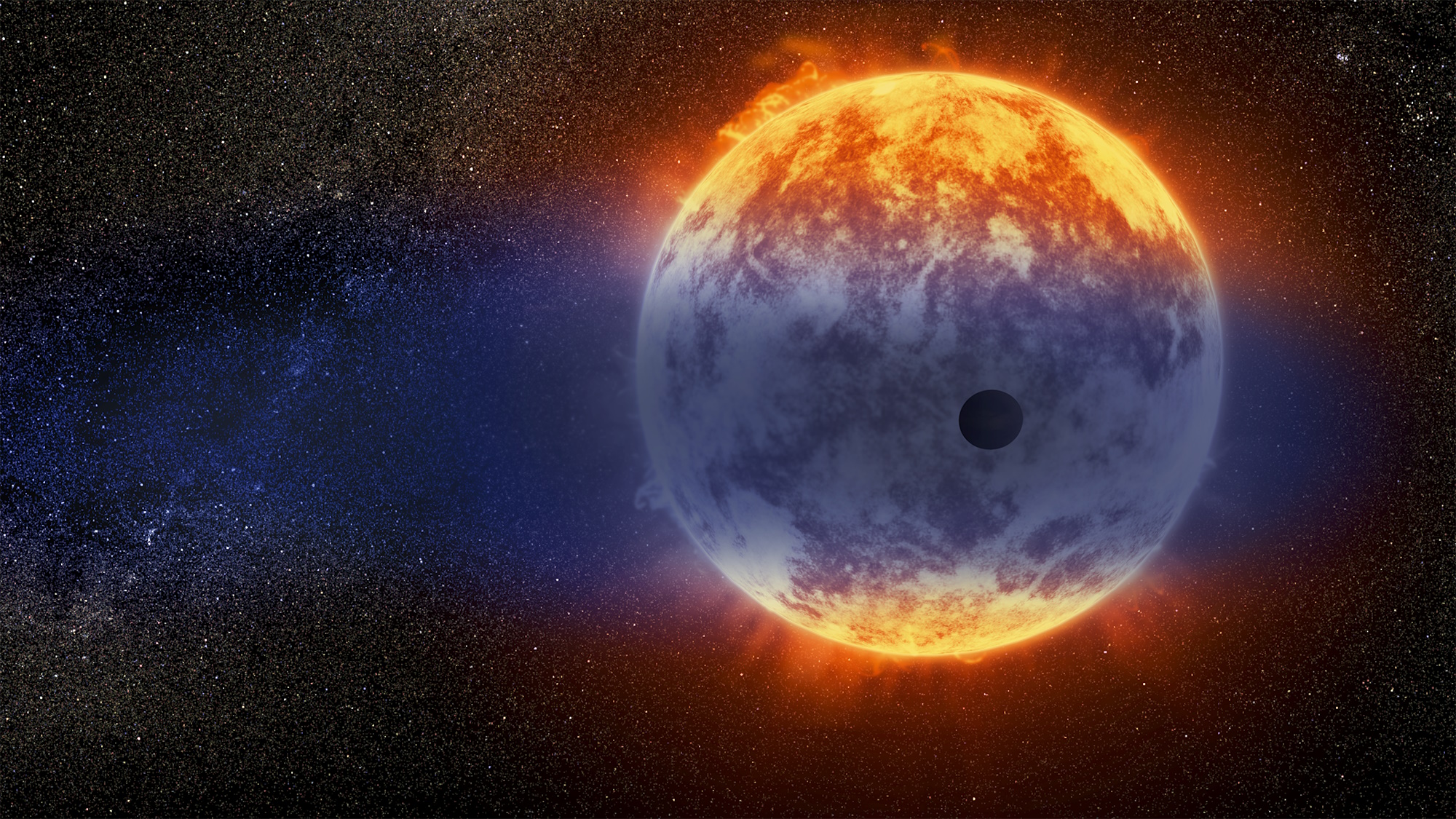

As our telescope technology improves, however, we’re likely to enter a new era in the coming years and decades: an era where we’ll be able to directly image Earth-sized planets at Earth-like orbital distances around Sun-like stars. These exo-Earths are some of the best candidates for inhabited planets out there, as with such similar conditions to Earth, a planet that we know isn’t just inhabited, but has been teeming with life for nearly all of its history — and with complex, differentiated life for more than half a billion years — some, many, or maybe even nearly all of them will have life on them as well.

With that new generation of telescopes, we won’t just be able to image these planets, but to construct coarse maps of them as well. Here’s how that’s possible.

In order to directly image an Earth-sized planet at an Earth-like distance around a Sun-like star, we need superior telescope technology to what’s available today. Even with the world’s largest ground-based or space-based telescopes, we can only directly image giant planets that are sufficiently separated from their parent stars. Unless these planets are at extreme separations, where the light from the parent star can be completely blocked by a coronagraph, or the stars themselves are sufficiently dim that their planets are sufficiently self-luminous (such as in the infrared) to appear directly in our instruments, our current generation of technology will be incapable of seeing or imaging them.

However, this will not be true in just one or two decades. If you traveled far away from our own Solar System and looked back, attempting to see Earth, if you could:

- block out the light from the Sun,

- while capturing the reflected visible light (or the emitted infrared light) from Earth,

you would be able to directly image our planet. Of course, the Sun is approximately a factor of a hundred billion (1011) more intrinsically bright than the Earth is, so an incredible amount of the Sun’s light — or, for an Earth-like exoplanet, the parent star’s light — must be blocked out in order to be able to image the planet directly.

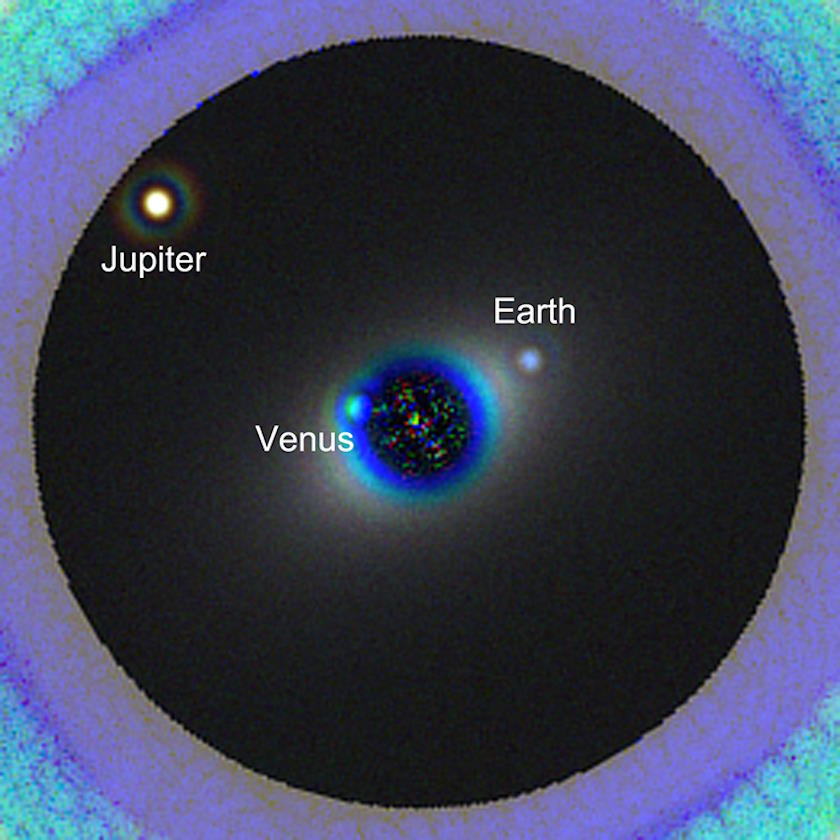

There are two paths to blocking out the light from the parent star: coronagraphy or with a piece of equipment like a starshade. A coronagraph is a small mask, internal to the telescope, that can be placed along our line-of-sight, blocking the light from whatever target we’re pointing at (including a star) while allowing the light from all other objects (including a planet orbiting that star) to enter the telescope. Coronagraphs are tricky things, though, because simply “placing a mask” in front of the star won’t block 100% of the star’s light, due to the wave-like properties of light, including interference and diffraction. Even with the star completely behind the disk, the starlight striking the edge of the disk, producing a bright circular pattern of fringes around it.

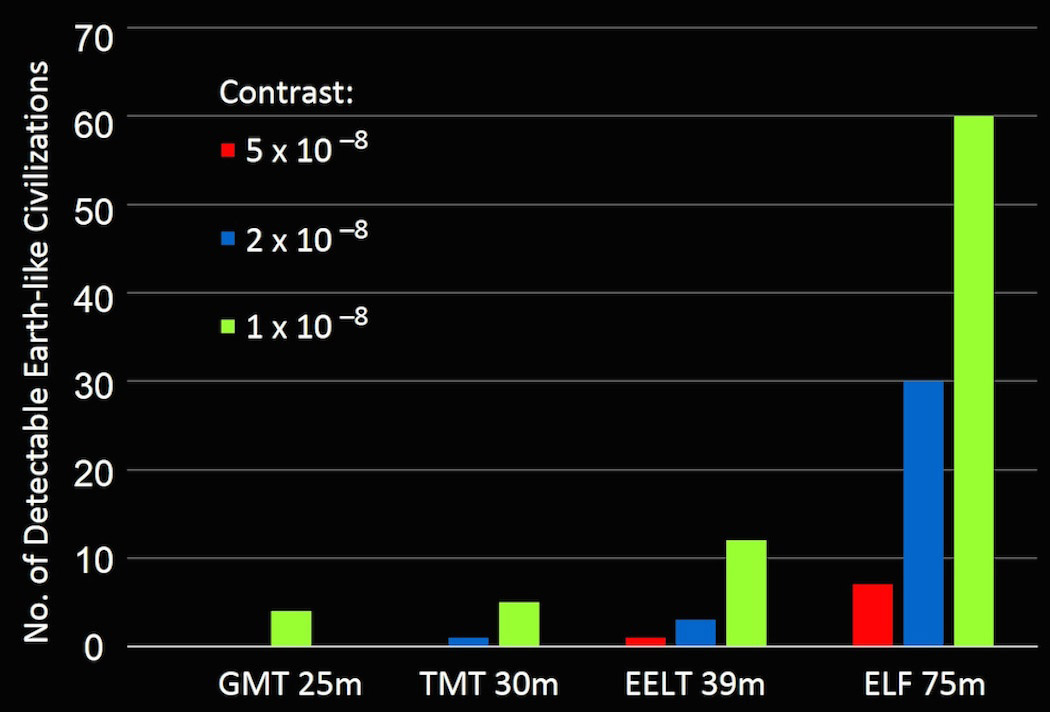

Modern coronagraphs can block as much as 999,999-parts-in-a-million of the incoming light, which is wonderful for directly imaging large planets at large distances from their parent star, but insufficient for imaging Earth-like planets at Earth-like distances around Sun-like stars. Coronagraph technology is improving, as are software/machine learning techniques to extract the light from a planet within those unavoidable fringes, which should allow larger brightness contrasts (around 1-part-in-108) on the upcoming Nancy Roman Telescope, and are expected to allow us to get down to sensitivities that will allow exo-Earth direct imaging with NASA’s upcoming Habitable Worlds Observatory: the flagship astrophysics mission slated after Roman. The largest ground-based telescopes planned for the 2030s, of 30-meter class sizes, will get close to this threshold, but are expected to fall short by a couple of orders of magnitude.

The other option is to go to space, and along with your space telescope, to send a far-flung external “mask” between your telescope and your parent star. This mask is known as a sunshade, and has a mathematically perfect, pinwheel-like shape that, in theory, should block 100% of the parent star’s light while allowing 100% of the planet’s light (particularly if the planet is located in the “gaps” between the points of the pinwheel) through.

In practice, starshades can achieve much better brightness contrasts than even the best coronagraphs can, but there’s a severe limitation to them. Unlike telescopes with coronagraphs, which can literally point at a star or stellar system located anywhere on the sky, telescopes with starshades can only point in one direction: along the line-of-sight connecting the starshade to the telescope. This means, if you want to image a different target than the one your telescope-starshade combination is presently aligned with, you need to physically move either the telescope, the starshade, or both. Considering that the separation distances needed are on the order of tens of thousands of kilometers, this severely limits the number of systems that can be imaged in a reasonable amount of time with a starshade.

A similar limitation would apply to the one idea that can actually take an extended image of an Earth-sized exoplanet: a gravity-based telescope equipped with a coronagraph.

The Sun, as we’ve known since the time of Einstein and Eddington, has enough gravity that it can bend, or deflect, the light from objects that appear behind it but very close to the line-of-sight connecting the observer to the Sun. This doesn’t just apply to stars that happen to be located near the Sun during a total solar eclipse, but also to any light source located behind the Sun when you obscure it with a coronagraph.

There’s an idea that if you move a telescope far enough away from the Sun and block out the Sun’s light, you can create what’s known as a solar gravity telescope, where the gravitational lensing enhancement from the Sun can stretch out and magnify an observed Earth-like exoplanet’s light so that it can occupy thousands of pixels at once, rather than just one. It’s the best — and arguably, only — way, with current technology, to take a multi-pixel image of an exoplanet located multiple light-years away. With a space telescope located more than 500 times the Earth-Sun distance away, this is indeed possible, but it’s an enormous investment for an image of just one exoplanet.

You might ask if there’s a quicker, cheaper, faster, and easier way than a multi-billion dollar space telescope mission to get an image of an exoplanet, even if it’s just one pixel?

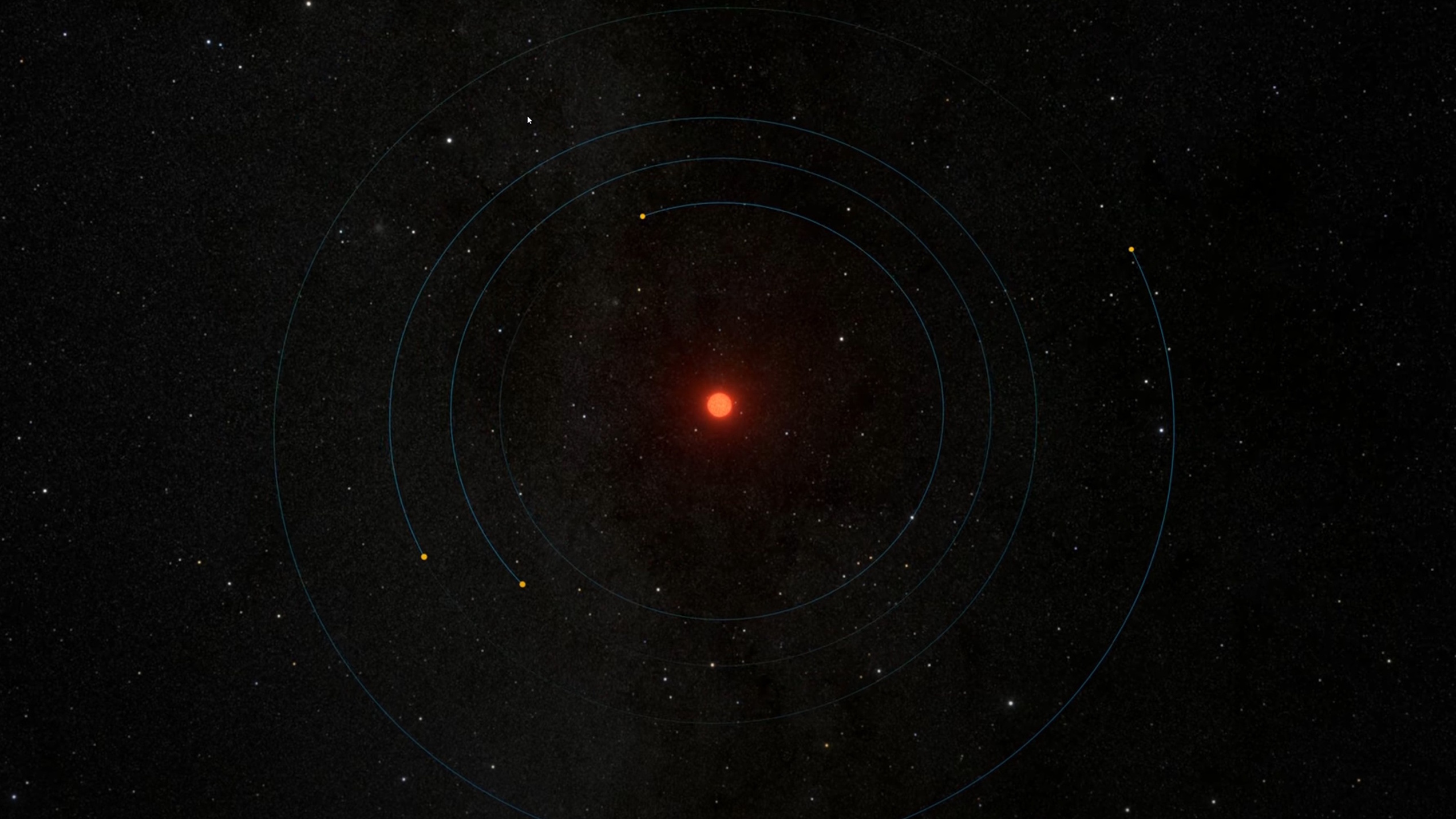

Indeed, there is: the concept is called ELF: ExoLife Finder. Instead of one large telescope, ExoLife Finder proposes building an array of mirrors in a ring, where each mirror reflects the light from a single target toward a secondary assembly, which will — with a combination of adaptive optics, interferometry, and photonics technologies — allow us to create a direct, one-pixel image of any exoplanet that we point it at. With expected optical contrasts of ~108, and with machine learning technologies applied atop that, ExoLife Finder’s capabilities vastly exceed that of any of the proposed 30-meter class telescopes, and the reason to understand is simple.

Imagine that you had a large-diameter primary mirror to your telescope, and that the telescope was solid and filled-in completely with mirror. What determines what you see?

- The physical diameter of the telescope, and how many wavelengths of light fit across it, is what determines your resolution.

- The total collecting area of your telescope, on the other hand, determines how bright the object you’re observing appears.

If you imagined a 100-meter telescope, it would be heavy and exceedingly difficult to control. However, if you only built the “edges” of this telescope, you could achieve the resolution you require: the same resolution as the large, filled-in version.

With less light-gathering power as the trade-off, you’d simply need to increase your observing time in order to get a sufficiently bright image: one capable of conducting the science we need. And all we need, for real, is just one pixel. Because with only one pixel, we can map out the properties of the planet’s surface, atmosphere, oceans, continents, icecaps, and even signs of life.

How can we do this from just one pixel?

A great analogy is to consider cool, low-mass stars: red dwarf stars that only show up as one single pixel in our instruments. We can take the light from that star and break it up spectroscopically: into the different wavelengths of light that compose it. By mapping out the star’s energy profile, we can determine what its equilibrium temperature is. By watching how the star dims and brightens over time, we can infer its rotational period and identify the size and temperature of any starspots present on its surface. And by looking for transient events coming from the star — or temporary variations in its brightness — we can identify the strength, duration, and magnitude of any space weather, such as stellar flares or coronal mass ejections, that are emitted by the star itself. We’ve done this many times already, with tremendous success.

So imagine, now, that we don’t just have a static, one-pixel image of an exoplanet, but rather of a spectrum from that exoplanet, and that we get to record that spectrum at every moment over long periods of time. Imagine that we don’t just have it in visible light, but in infrared light as well, as a significant portion of the near-infrared spectrum is still visible from the ground.

What could we see?

- As different portions of the planet’s surface rotated in-and-out of view from our perspective, we’d be able to infer the planet’s overall rotation rate.

- As the “bluer” parts of the planet rotated in-and-out of view, we’d be able to identify how much of the planet’s surface is covered in ocean, as well as how the fraction of oceanic coverage varied as the planet rotated.

- Similarly, we could perform the “ocean” analysis for the other portions of the planet: continents and ices, from glaciers, ice-covered mountaintops, and polar icecaps, particularly.

- As natural variations in reflectivity appeared superimposed atop of these rotational features, we’d be able to draw inferences about clouds and cloud cover over time, with a spectral analysis even potentially revealing the composition of those clouds.

As remarkable as these effects are, this is just what we can learn from short-term variations.

Credit: NASA Ames/JPL-Caltech/T. Pyle

When we start looking at longer-term variations, we can start to see periodic changes that occur as the planet moves around its parent star in orbit.

- As the planet’s axis changes in terms of which “pole” it tipped toward or away from the parent star, we’ll see polar features, such as icecaps, grow and retreat in a periodic fashion.

- If there’s life on the planet, we should see the continents green-and-brown with seasonal variations, with spectral signatures even potentially revealing what types of chemical products are emitted by life processes on that world.

- If there’s a large, massive satellite to this planet, even if we can’t image its moon(s) directly, they should create orbital variations in the planet’s motion itself, which can reveal the mass of the moon relative to the planet as well as its orbital distance.

- And if we can measure the polarization of the light coming from the planet, and how that polarization changes over time due to the electromagnetic effect of Faraday rotation, we could even detect whether this exoplanet possesses a planet-wide magnetic field, and quantify its magnitude in the process.

In other words, from a dedicated imaging campaign over time, with spectroscopic and polarization capabilities plus the ability to quantify variations and periodicities in the light emitted from the planet itself, we can not only determine all of these properties, but could in principle reconstruct a coarse map of the planet, even from just one single pixel of data.

The point of all this is to recognize that if our goal is to find an inhabited planet that’s out there, our best bet is simply to take a one-pixel image of an Earth-sized planet at Earth-like distances from a Sun-like star. After all, in our Milky Way, we know how many Sun-like stars are out there, and recent estimates have suggested that there are around 10 billion Earth-sized planets in Earth-like orbits around those stars. If we can gain the ability to directly image a few dozen of them, or perhaps even a few hundred of them, then the odds are very strong that many of them will have complex features on them: atmospheres, continents, ices, oceans, and raw ingredients that are conducive to, but not conclusive of, life.

If every planet in the Universe is a lottery ticket, we have to recognize that there are probably an array of prizes out there, and that the probability of winning any of those prizes are completely unknown. Here on Earth, there’s no denying that we’re definitely among the winners, as life (and intelligent, technologically advanced life, at that) has arisen here. But what are the other prizes out there? What are the odds of winning those prizes? And are we even the “grand prize,” or are there even more spectacular outcomes that we’re going to encounter as we continue the search?

The only way to answer these questions is to look. If nature is kind, or perhaps if nature simply isn’t utterly cruel, the 21st century will mark the moment in our civilization’s history when we realize we truly aren’t alone in the Universe. If we reach that milestone, the world will never be the same.