Messier Monday: The Dumbbell Nebula, M27

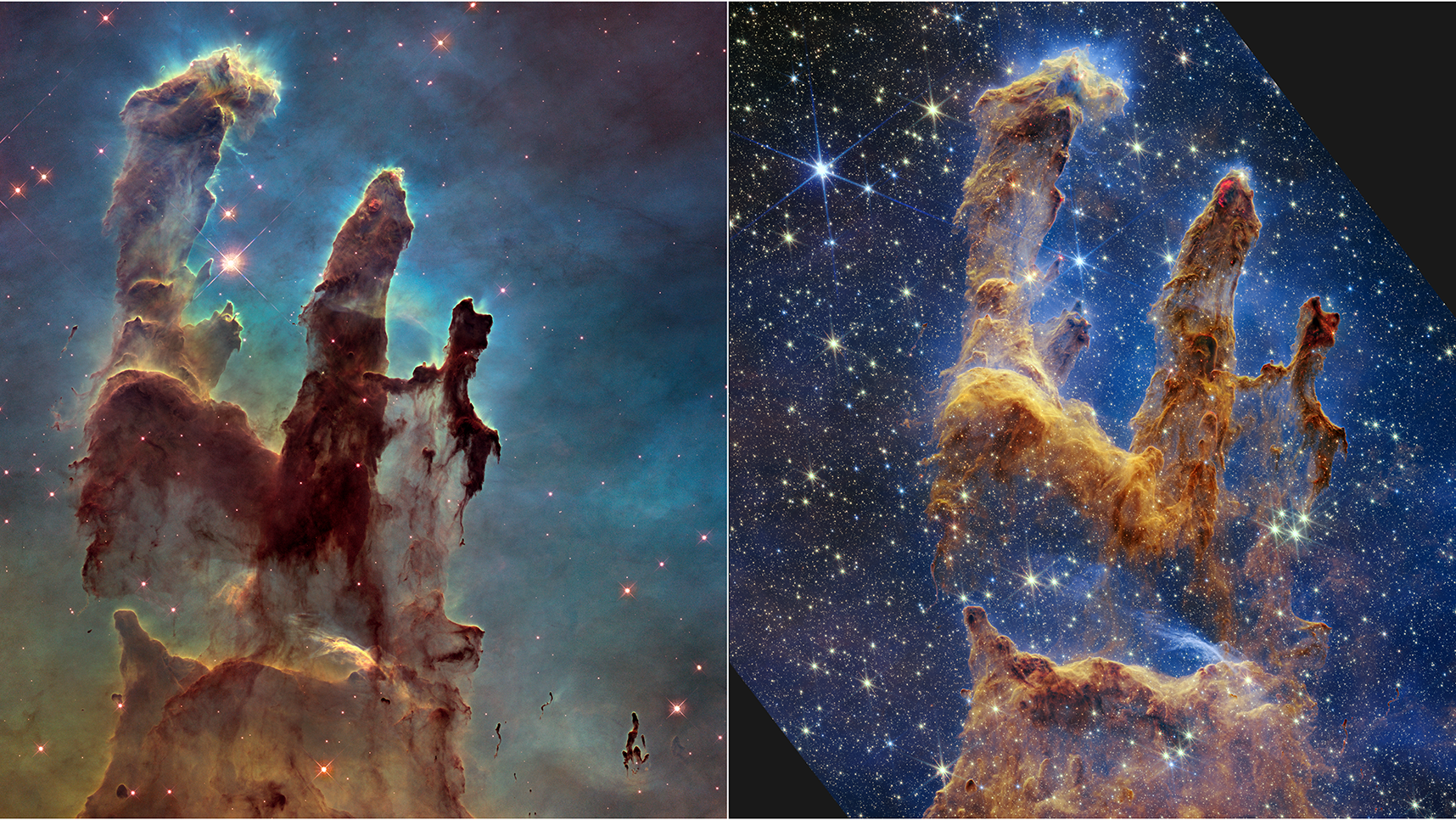

The brightest “planetary nebula” is actually a Sun-like star in its final death throes!

“When he shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun.” –William Shakespeare

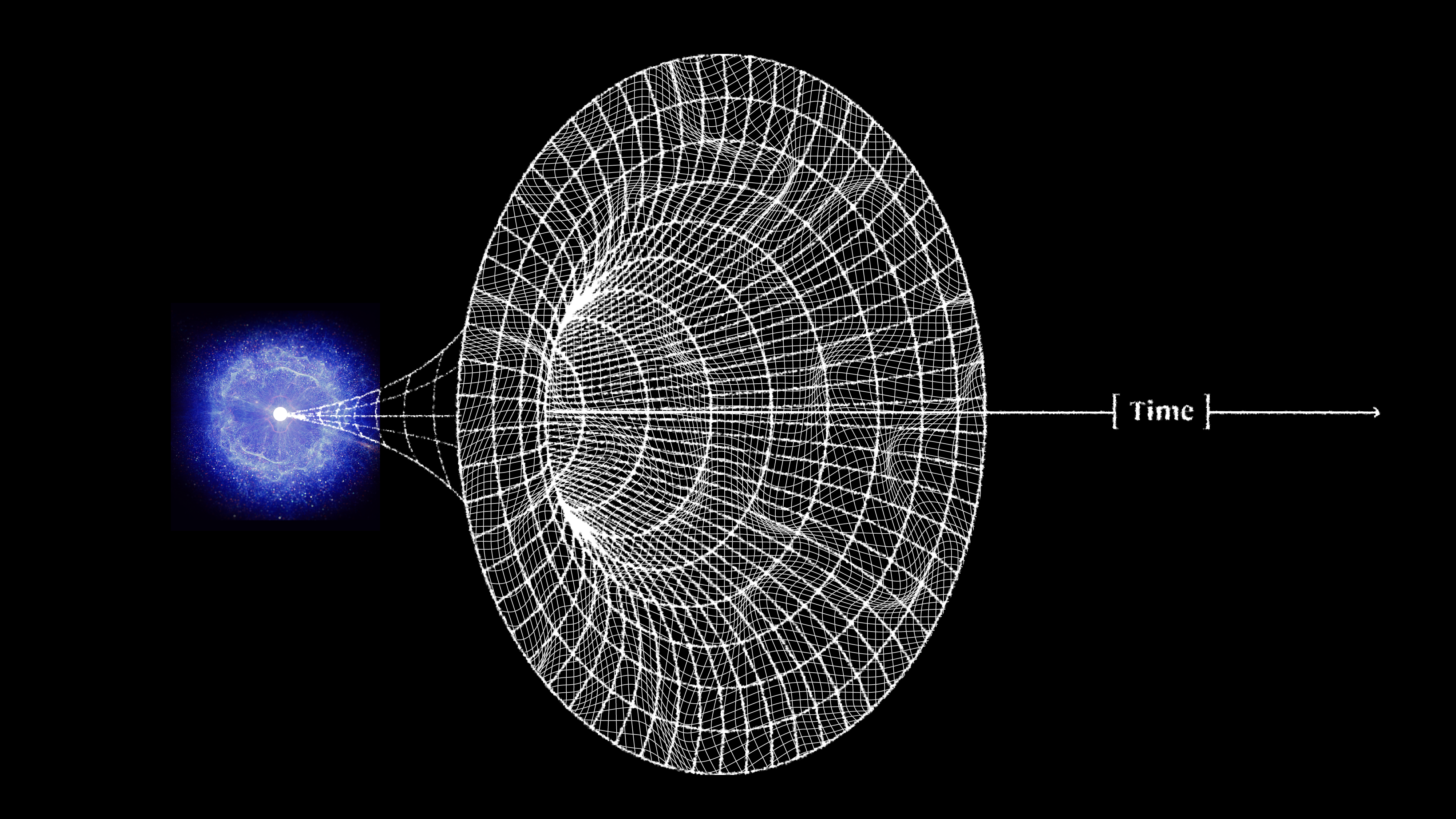

When you think of the stars in the night sky, they may seem eternal, but you know better. In fact, the vast majority of the brightest ones we can see are either very bright, young blue giants that are destined to be short lived, or old, red giants that have burned through the majority of their fuel. In both cases, these stars are nearing the end of their lives. But did you know that — just beyond the reach of your naked eye’s capabilities — lie a number of recently deceased red giants that were bright, shining stars just a few hundred thousand years ago?

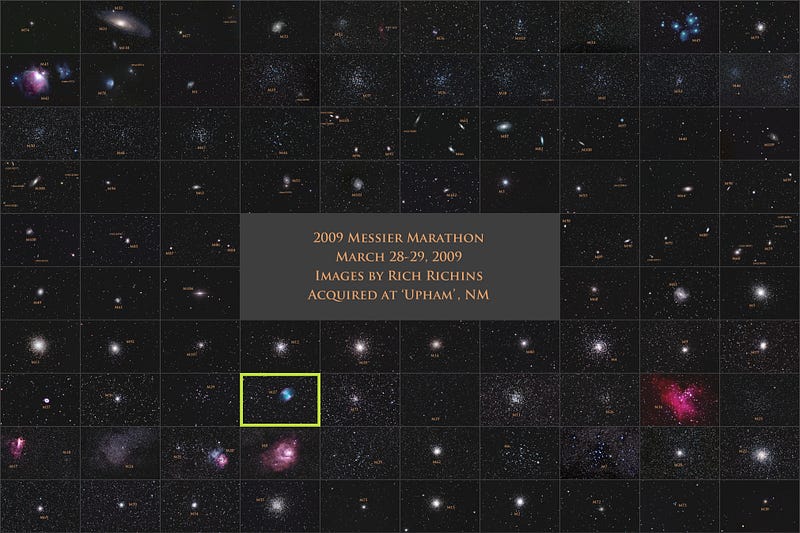

To the very first humans on Earth, these stellar remnants would have been visible as true, simple stars: points of light in the sky. There are four objects like this in the Messier catalogue, the first large-scale compilation of deep sky objects easily visible with simple equipment (a small telescope or binoculars) from Earth. Today’s object — Messier 27, the Dumbbell Nebula — was not only the first one discovered, it’s also the brightest one from our vantage point. As the solstice has recently passed us, it will be a spectacular object all summer long! Here’s how to find it.

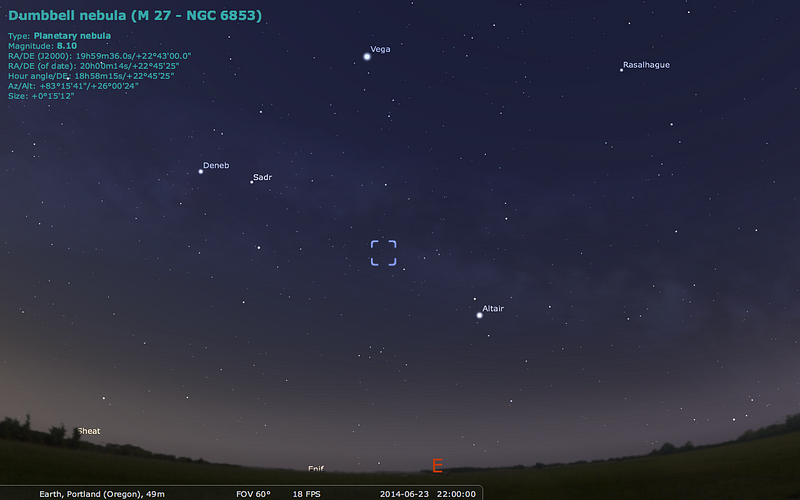

After the Sun goes down, stars begin to come out en masse in the night sky. The brightest ones appear first, and among them in the East are the three stars making up the prominent Summer Triangle: the trio of Vega, Altair and Deneb. (They are the fifth, twelveth, and nineteenth brightest stars in the entire sky, respectively.) Vega is easily identifiable as the brightest of the three, while Deneb and Altair begin the night a little closer to the horizon.

If you start from Deneb and navigate towards the opposite side of this triangle, you’ll see a pattern of six stars that are sometimes known as the Northern Cross.

But it’s what you’ll see if you begin at Altair and navigate back towards Deneb that interests you tonight if you’re hunting for Messier 27! About a quarter of the way back to Deneb, you’ll find the prominent orange giant γ Sagittae, a star much younger than our Sun is. This star was born some 750 million years ago as a massive, blue B-class star. It’s run out of the hydrogen fuel that was initially in its core and has since expanded to become a red giant, burning helium in its central region instead.

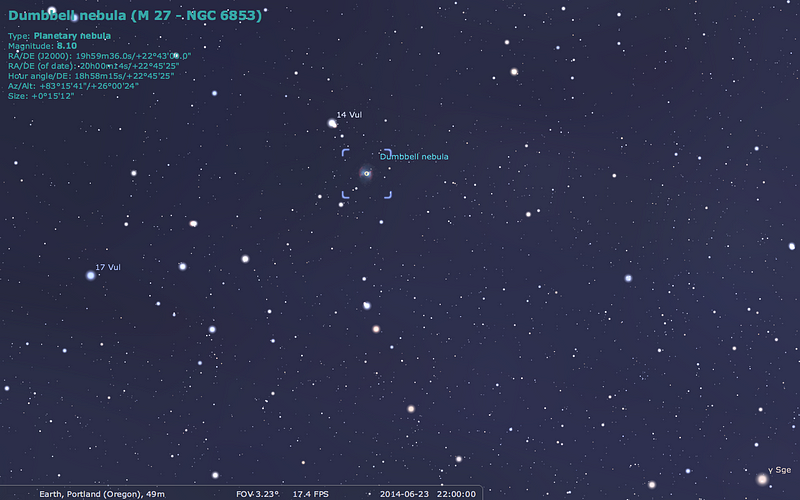

At some point in the future, it — and all Sun-like stars (stars between about 40% and 400% of our Sun’s mass) — will run out of helium as well, and when it does, it might begin to look an awful lot like Messier 27. If you continue the line connecting Altair to γ Sagittae by another 2°, you’ll come to a barely visible naked-eye star: 14 Vulpeculae. The faint, extended “cloud-like” object you’ll see right next to it through binoculars or a small telescope is the Dumbbell Nebula you’re looking for.

This object — the first of its class — was discovered by Charles Messier himself back in 1764, who described it thus:

Nebula without star, discovered in Vulpecula, between the two forepaws, & very near the star 14 of that constellation, of 5th magnitude according to Flamsteed; one can see it well with an ordinary telescope […] it appears of oval shape, & it contains no star.

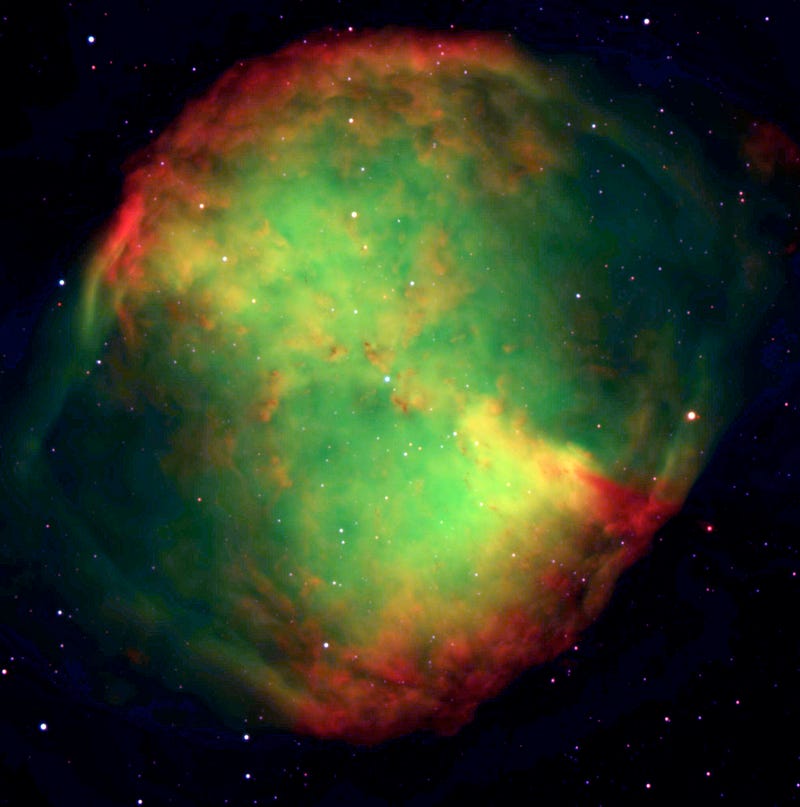

Even through a good-sized telescope, the human eye will only perceive this as white, although the two-lobed structure will be clear. But color astrophotography brings out some spectacular detail here.

You’ll notice that there appears to be a star at the center of this nebula, and this is no mere coincidence or chance alignment: this once-giant star has collapsed down to a dwarf, but a tremendously hot one at about 85,000 K! (About 14 times as hot as the surface of our Sun, for comparison.)

The different colors are indicative of different elements in different ionization states, with red being a telltale sign of ionized hydrogen. But if you focus in on the narrow-band colors that other elements make, you’ll find something more than simple hydrogen.

The bright green glow you see is highlighting oxygen atoms in their rare, doubly-ionized state (where it’s missing two electrons). How did we arrive at this configuration, with two lobes of hydrogen gas on the outskirts, a sea of very hot oxygen gas towards the center, and an ultra-hot dwarf star at the center?

You see, this nebula is at most 48,000 years old, with many estimates placing it closer to the 10,000 year range! Prior to that, it was a giant star, burning through helium fuel in its core and hydrogen in its outer layers. When the core ran out of helium fuel, it contracted and heated up, and the elevation in radiation pressure first blew off the star’s outer, hydrogen-rich layers.

But it didn’t simply blow those layers off spherically, as our Sun most probably will. You see, Messier 27 is part of a binary star system, and that second star — the one that’s still burning through its fuel — helps eject that blown-off mass in the dual-lobed trajectory we see. In fact, some of the mass of the original star is flung even farther than typical images of this nebula show!

In addition to the hydrogen, the relatively rapid contraction of this star causes it to heat up, and these increased temperatures trigger bursts of nuclear fusion that can expel portions of the inner layers of the star as well. Among other elements like sulphur and nitrogen, that’s where the oxygen comes from!

The inner core of this star will eventually contract down to a white dwarf: a very hot star that shines because of the energy of its gravitational contraction! This core is about the mass of the Sun, but it’s contracted down to only about the physical size of the Earth. This stores a tremendous amount of heat and energy in the dwarf star, but because it’s so small, it can only radiate this energy away very slowly. It will take somewhere around 10^14 years — or about 10,000 times the age of the present Universe — for this object to cool enough to stop emitting visible light.

In the meantime, the nebula is expanding, as the gas that’s “gently” blown off from this until-recently-a-normal-star returns to the interstellar medium, where it will help form future generations of stars, planets, complex chemicals, and possibly life. When we’re looking at a planetary nebula, we’re watching part of the cosmic life cycle of death and rebirth.

And if you take a close look with, say, the Hubble Space Telescope, you’ll find that there are many “knots” of gas, rich in heavy elements, that form in this (and all) planetary nebulae!

So enjoy this treasure of the night skies — the brightest planetary nebula — and think of all the hundreds of billions (if not trillions) of stars that already went through this in our galaxy alone to help create the solar systems, planets, and life that we have right now.

And that’s your connection to the cosmos on this Messier Monday! Take a look back at all our previous Messier Mondays here:

- M1, The Crab Nebula: October 22, 2012

- M2, Messier’s First Globular Cluster: June 17, 2013

- M3, Messier’s First Original Discovery: February 17, 2014

- M4, A Cinco de Mayo Special: May 5, 2014

- M5, A Hyper-Smooth Globular Cluster: May 20, 2013

- M7, The Most Southerly Messier Object: July 8, 2013

- M8, The Lagoon Nebula: November 5, 2012

- M10, A Perfect Ten on the Celestial Equator: May 12, 2014

- M11, The Wild Duck Cluster: September 9, 2013

- M12, The Top-Heavy Gumball Globular: August 26, 2013

- M13, The Great Globular Cluster in Hercules: December 31, 2012

- M14, The Overlooked Globular: June 9, 2014

- M15, An Ancient Globular Cluster: November 12, 2012

- M18, A Well-Hidden, Young Star Cluster: August 5, 2013

- M20, The Youngest Star-Forming Region, The Trifid Nebula: May 6, 2013

- M21, A Baby Open Cluster in the Galactic Plane: June 24, 2013

- M25, A Dusty Open Cluster for Everyone: April 8, 2013

- M27, The Dumbbell Nebula: June 23, 2014

- M29, A Young Open Cluster in the Summer Triangle: June 3, 2013

- M30, A Straggling Globular Cluster: November 26, 2012

- M31, Andromeda, the Object that Opened Up the Universe: September 2, 2013

- M32, The Smallest Messier Galaxy: November 4, 2013

- M33, The Triangulum Galaxy: February 25, 2013

- M34, A Bright, Close Delight of the Winter Skies: October 14, 2013

- M36, A High-Flying Cluster in the Winter Skies: November 18, 2013

- M37, A Rich Open Star Cluster: December 3, 2012

- M38, A Real-Life Pi-in-the-Sky Cluster: April 29, 2013

- M39, The Closest Messier Original: November 11, 2013

- M40, Messier’s Greatest Mistake: April 1, 2013

- M41, The Dog Star’s Secret Neighbor: January 7, 2013

- M42, The Great Orion Nebula: February 3, 2014

- M44, The Beehive Cluster / Praesepe: December 24, 2012

- M45, The Pleiades: October 29, 2012

- M46, The ‘Little Sister’ Cluster: December 23, 2013

- M47, A Big, Blue, Bright Baby Cluster: December 16, 2013

- M48, A Lost-and-Found Star Cluster: February 11, 2013

- M49, Virgo’s Brightest Galaxy: March 3, 2014

- M50, Brilliant Stars for a Winter’s Night: December 2, 2013

- M51, The Whirlpool Galaxy: April 15th, 2013

- M52, A Star Cluster on the Bubble: March 4, 2013

- M53, The Most Northern Galactic Globular: February 18, 2013

- M56, The Methuselah of Messier Objects: August 12, 2013

- M57, The Ring Nebula: July 1, 2013

- M58, The Farthest Messier Object (for now): April 7, 2014

- M59, An Elliptical Rotating Wrongly: April 28, 2014

- M60, The Gateway Galaxy to Virgo: February 4, 2013

- M61, A Star-Forming Spiral: April 14, 2014

- M63, The Sunflower Galaxy: January 6, 2014

- M64, The Black Eye Galaxy: February 24, 2014

- M65, The First Messier Supernova of 2013: March 25, 2013

- M66, The King of the Leo Triplet: January 27, 2014

- M67, Messier’s Oldest Open Cluster: January 14, 2013

- M68, The Wrong-Way Globular Cluster: March 17, 2014

- M71, A Very Unusual Globular Cluster: July 15, 2013

- M72, A Diffuse, Distant Globular at the End-of-the-Marathon: March 18, 2013

- M73, A Four-Star Controversy Resolved: October 21, 2013

- M74, The Phantom Galaxy at the Beginning-of-the-Marathon: March 11, 2013

- M75, The Most Concentrated Messier Globular: September 23, 2013

- M77, A Secretly Active Spiral Galaxy: October 7, 2013

- M78, A Reflection Nebula: December 10, 2012

- M79, A Cluster Beyond Our Galaxy: November 25, 2013

- M81, Bode’s Galaxy: November 19, 2012

- M82, The Cigar Galaxy: May 13, 2013

- M83, The Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, January 21, 2013

- M84, The Galaxy at the Head-of-the-Chain, May 26, 2014

- M85, The Most Northern Member of the Virgo Cluster, February 10, 2014

- M86, The Most Blueshifted Messier Object, June 10, 2013

- M87, The Biggest One of them All, March 31, 2014

- M88, A Perfectly Calm Spiral in a Gravitational Storm, March 24, 2014

- M90, The Better-You-Look, The Better-It-Gets Galaxy, May 19, 2014

- M91, A Spectacular Solstice Spiral, June 16, 2014

- M92, The Second Greatest Globular in Hercules, April 22, 2013

- M93, Messier’s Last Original Open Cluster, January 13, 2014

- M94, A double-ringed mystery galaxy, August 19, 2013

- M95, A Barred Spiral Eye Gazing At Us, January 20, 2014

- M96, A Galactic Highlight to Ring in the New Year, December 30, 2013

- M97, The Owl Nebula, January 28, 2013

- M98, A Spiral Sliver Headed Our Way, March 10, 2014

- M99, The Great Pinwheel of Virgo, July 29, 2013

- M101, The Pinwheel Galaxy, October 28, 2013

- M102, A Great Galactic Controversy: December 17, 2012

- M103, The Last ‘Original’ Object: September 16, 2013

- M104, The Sombrero Galaxy: May 27, 2013

- M105, A Most Unusual Elliptical: April 21, 2014

- M106, A Spiral with an Active Black Hole: December 9, 2013

- M107, The Globular that Almost Didn’t Make it: June 2, 2014

- M108, A Galactic Sliver in the Big Dipper: July 22, 2013

- M109, The Farthest Messier Spiral: September 30, 2013

Come back tomorrow for more wonders of the Universe, and don’t forget to join us next week for another deep sky wonder on another Messier Monday!

Enjoyed this? Leave a comment on the Starts With A Bang forum at Scienceblogs!