Merging supermassive black holes emit the most energy of all

- In terms of energy released, there are lots of events to consider in the Universe: stellar cataclysms, jets emitted by black holes, and black hole-black hole mergers.

- However, with the exception of the Big Bang, merging supermassive black holes are in a class all of their own.

- Here’s how merging supermassive black holes emit the most energy of any event, excepting the Big Bang, to ever occur within our Universe.

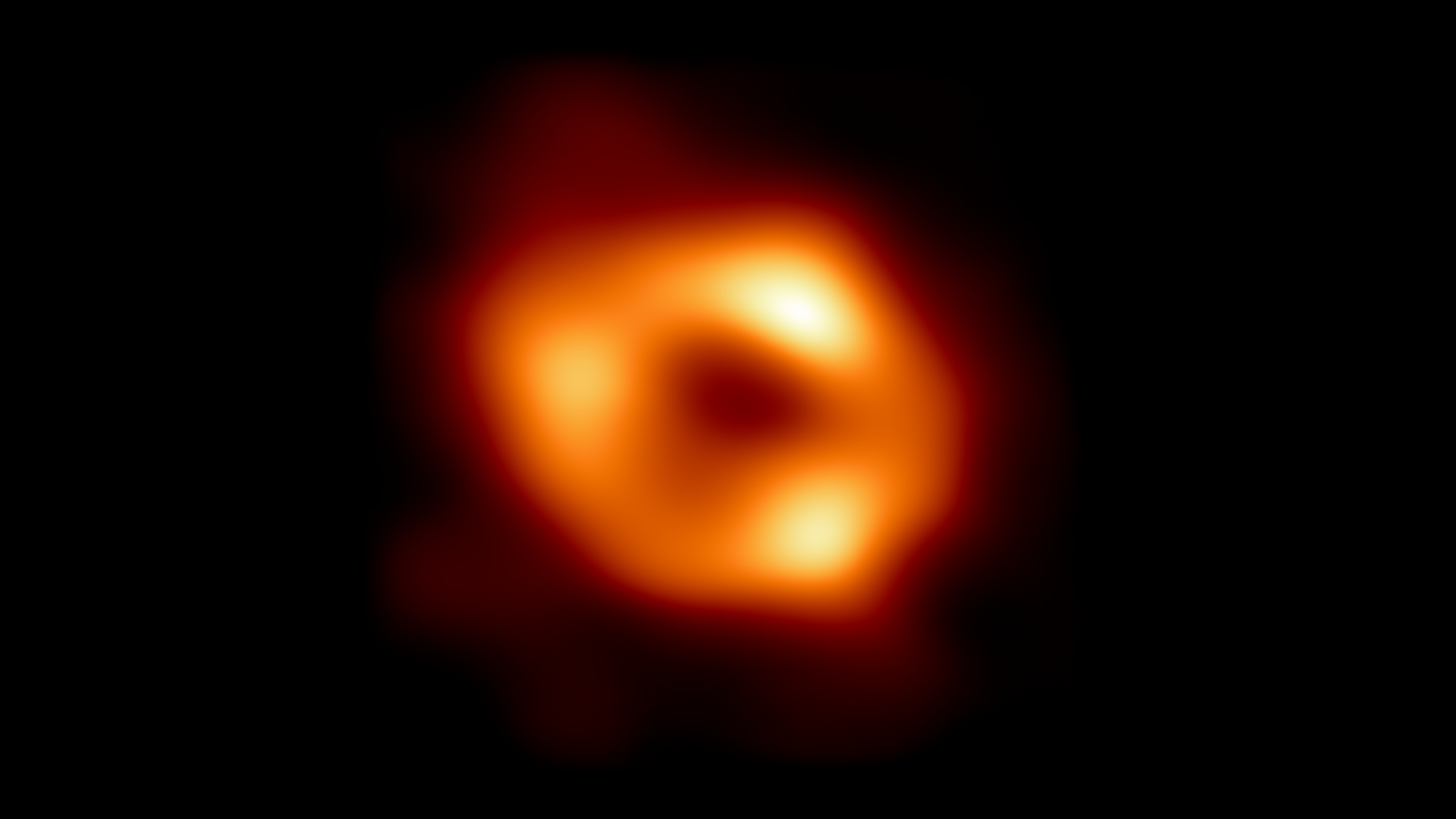

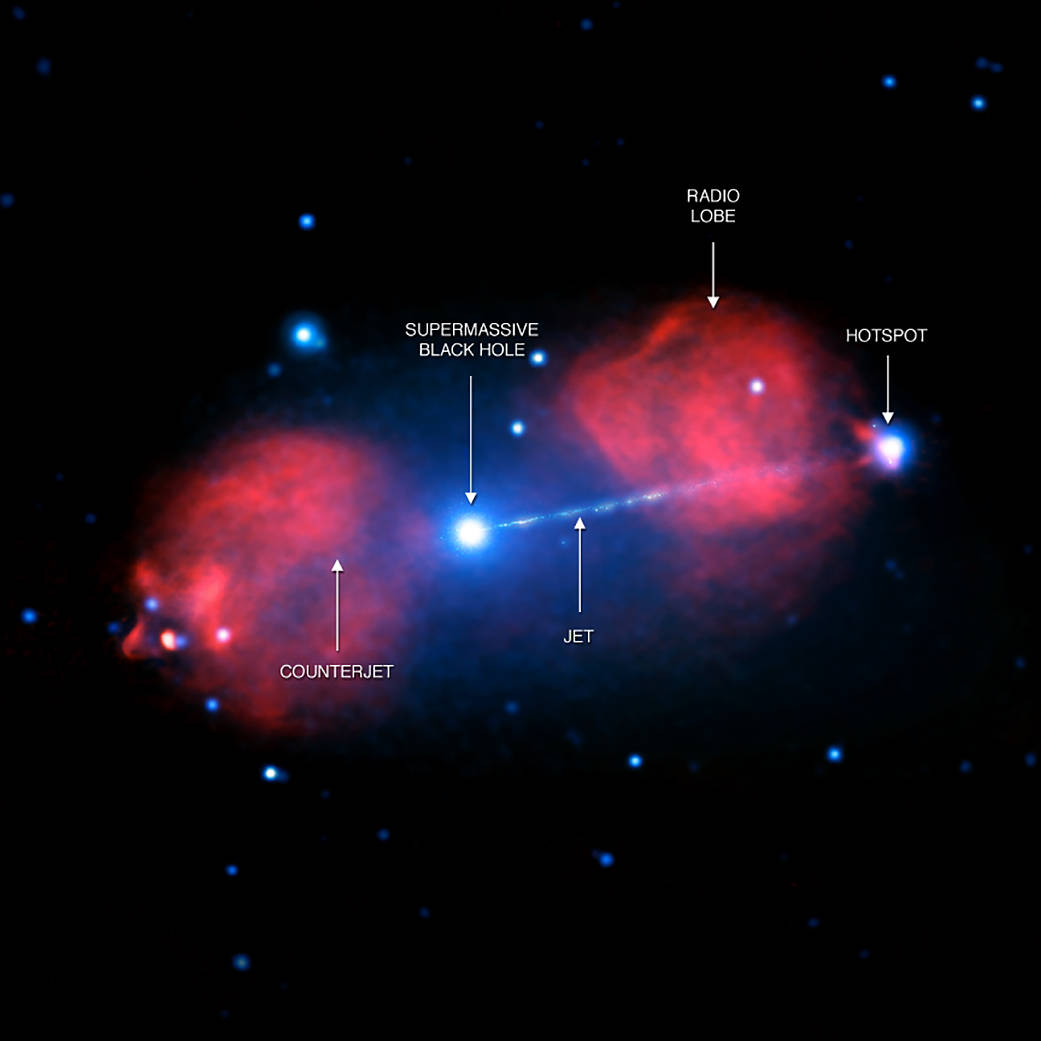

Back in 2020, NASA’s Chandra X-ray observatory made history by announcing the most energetic explosive event ever discovered in the Universe. In a galaxy cluster some 390 million light-years away, a supermassive black hole emitted a jet that created an enormous cavity in the intergalactic space of that galaxy cluster. The total amount of energy required to create this observed phenomenon? 5 × 1054 J: more energy to occur in any singular event ever seen since humanity first began studying the Universe. Only the Big Bang itself, which contains all of the energy within the entire Universe by definition, was more energetic.

But there’s another class of event that definitely exists in the Universe that can output even more energy in a shorter amount of time: the merger of two supermassive black holes. Although we’ve never seen such an event, it’s only a matter of time and technology until one reveals itself to us. When it does, the old record-holder will be shattered, possibly by an enormous amount. Here’s how.

There are lots of events that can be considered either explosions or cataclysms in the natural Universe, where a large amount of energy is released over a short period of time. A very massive star that reaches the end of its life will explode in a cataclysmic type II supernova, creating either a black hole or neutron star as a stellar corpse. Over the final few seconds of its life, it will release some ~1044 J of energy, with hypernovae (or superluminous supernovae) reaching up to or even over 100 times that “typical” amount.

For a long time, supernovae were used as the standard by which all other cataclysms were measured. As the brightest electromagnetic events in the sky, they could outshine entire galaxies, dependent on their individual brightnesses and the overall mass of the galaxy in question.

The only things that rivaled or exceeded the energy released in a supernova were gamma-ray bursts or larger-scale, extended events such as merging galaxies or galaxy clusters, or supermassive black holes feeding on enormous amounts of matter. During the 2010s, we uncovered the origin of at least some gamma-ray bursts: kilonovae, or the merging of two neutron stars. Between gravitational waves and electromagnetic radiation, a significant amount of mass — about ~1029 kilograms worth, or around 5% of a solar mass — gets converted into pure energy, leading to an energy release of about 1046 J.

On the other extreme, active galaxies and quasars can be even more energetic. Enormous amounts of mass, perhaps millions or even billions of solar masses worth, can get funneled into a central, supermassive black hole, where it gets torn apart, accreted, and accelerated. The matter and radiation emitted can reach a total of ~1054 J of energy, although it’s emitted over about a million years (or more) in time, making it a high energy but low power event.

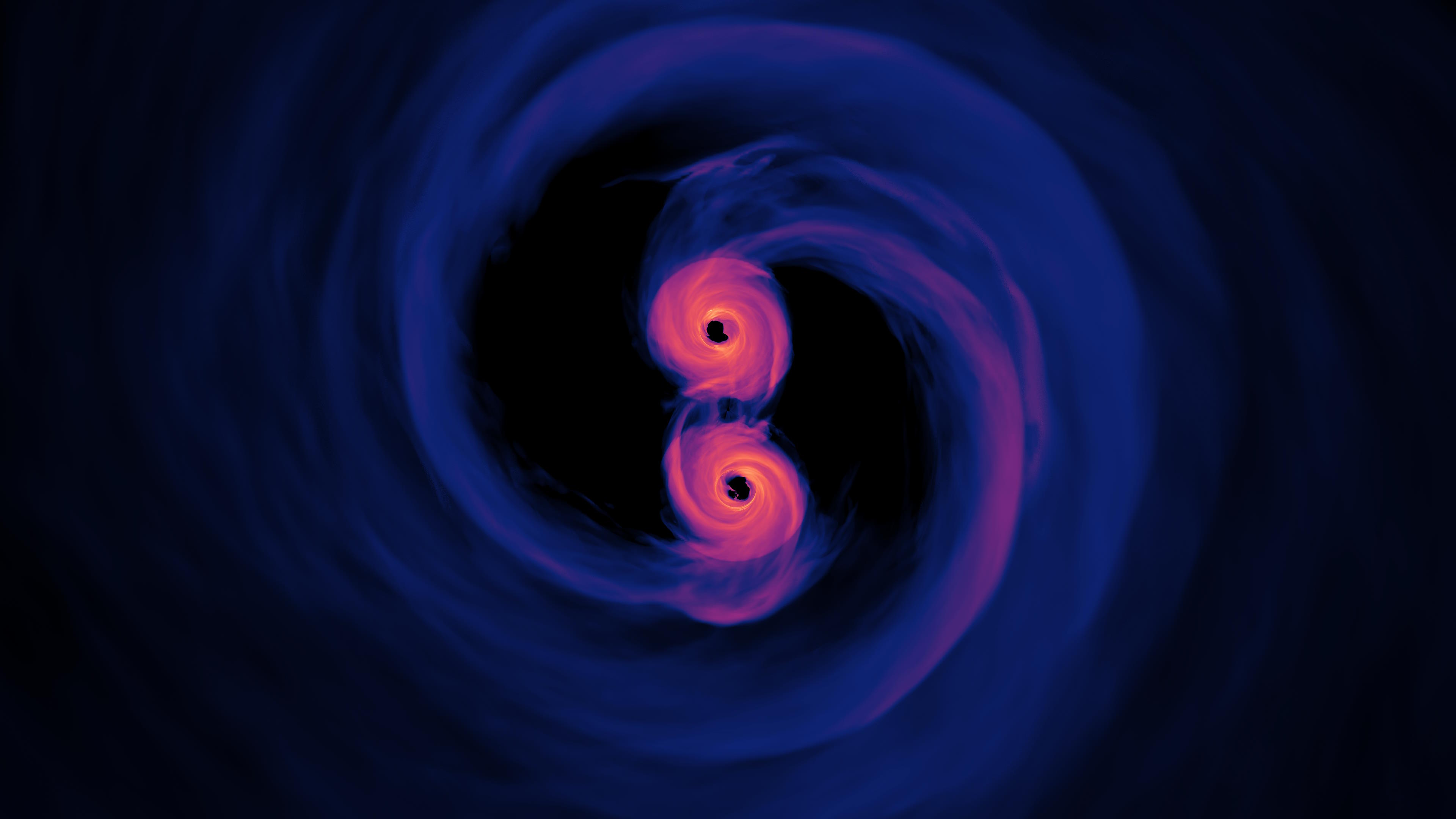

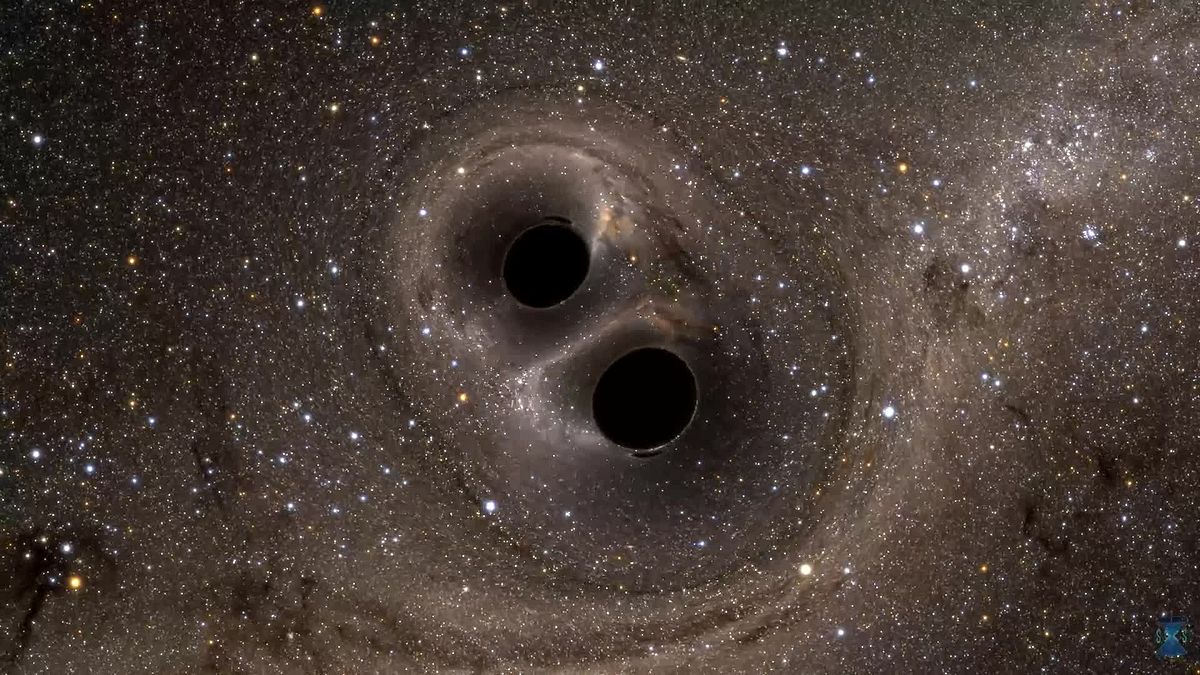

But the Universe gives us a way to emit even larger amounts of energy, and to do so on much shorter timescales. The key to unlocking this came last decade, when the NSF’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) direct detected the first gravitational wave event: from two merging black holes. For the very first one ever seen, two black holes of two different masses (36 and 29 Suns’ worth, respectively) merged together to produce a final-state black hole of a lesser (62 Suns’ worth) mass.

This was an enormously big deal, netting a number of scientists the 2017 Nobel Prize for the discovery of gravitational waves. Over the subsequent years, many more black hole-black hole mergers and merger candidates have been detected, with approximately 100 known so far (to date), and many more are expected in the new and upcoming runs of LIGO, Virgo, and KAGRA: humanity’s greatest gravitational wave detector array. In all cases, the same bizarre and fascinating behavior has been observed: large amounts of mass are converted into pure energy over a timescale of just a few milliseconds, or the final moments of the inspiral-and-merger of black holes.

Two points, in particular, are extremely interesting about these black hole-black hole mergers.

- In all cases, the peak power that was emitted, or energy-per-time, was about the same. They all outshone all the stars in the Universe, combined, for a tiny fraction-of-a-second, but the more massive mergers had their peak power output occur over longer periods of time, emitting more total energy.

- You can make a very simple approximation for the total amount of energy released in gravitational waves in a black hole-black hole merger: about 10% of the mass of the lower-mass black hole gets converted into pure energy, via Einstein’s E = mc². Although extremely lopsided mass ratios can bias this figure to somewhat lower values, “about 10%” remains an excellent approximation for all black hole-black hole mergers ever observed as of 2023.

For the first black hole-black hole merger ever discovered, the total amount of energy emitted was ~1048 J, and that occurred over a time interval that spanned just 200 milliseconds or so, leading to a fascinating possibility.

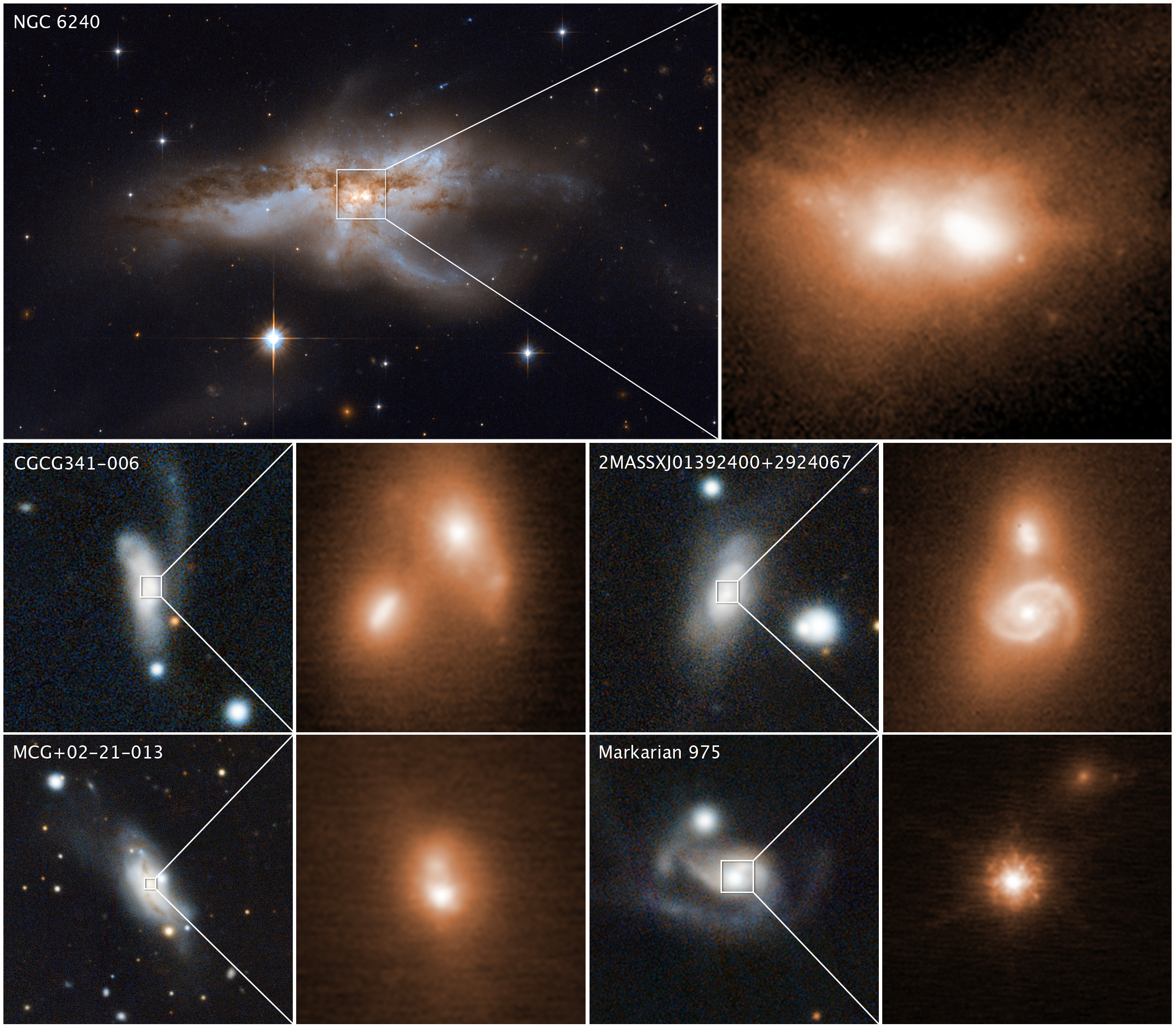

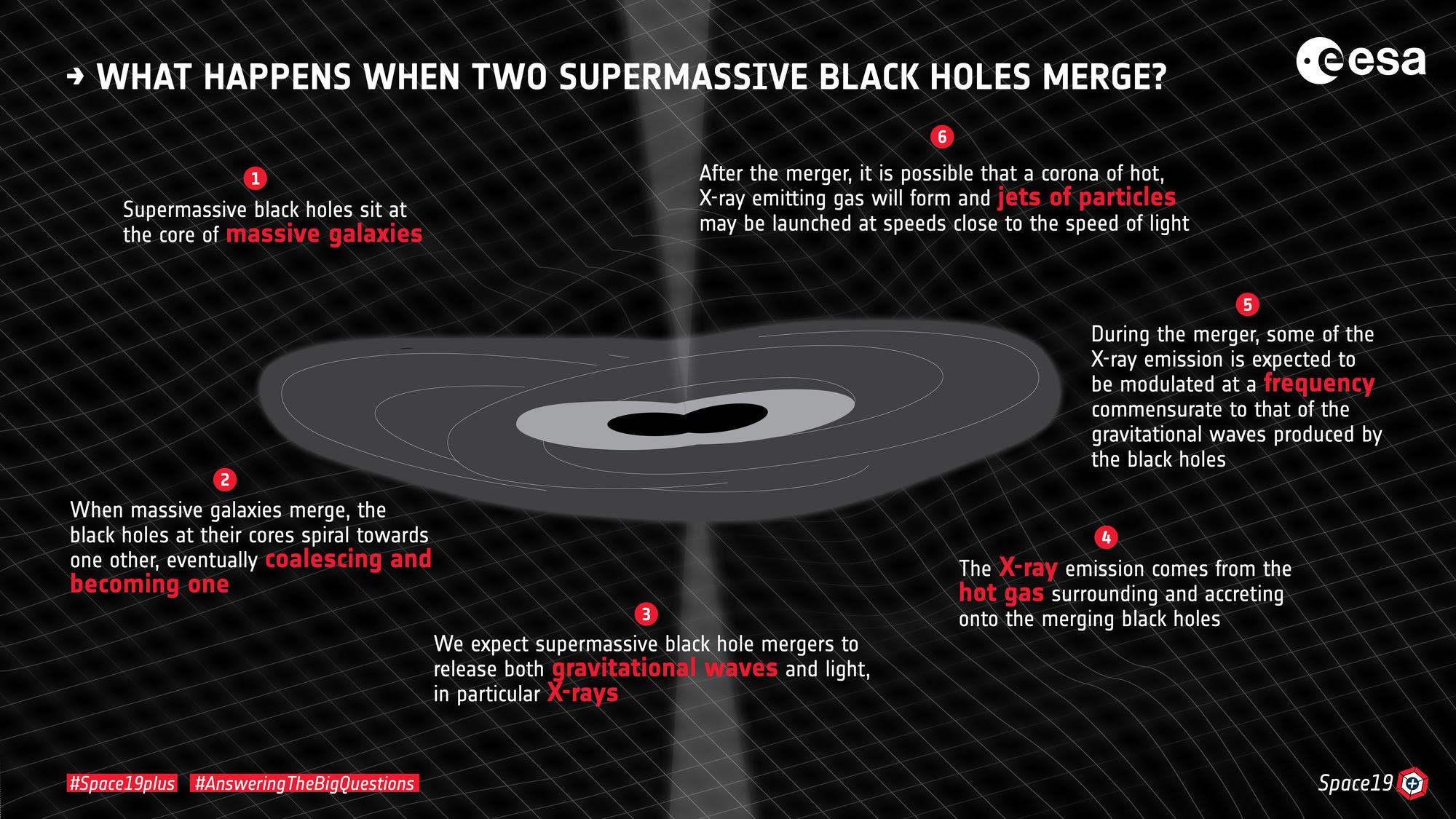

Instead of two “stellar mass” black holes merging together, where the masses of each black hole range from a few to a few dozen solar masses, we could look to the most massive black holes in the Universe: the supermassive ones found at the centers of galaxies. When they merge together, a series of events will unfold, resulting in the largest release of energy that — at least theoretically — should ever occur in our post-Big Bang Universe.

In particular:

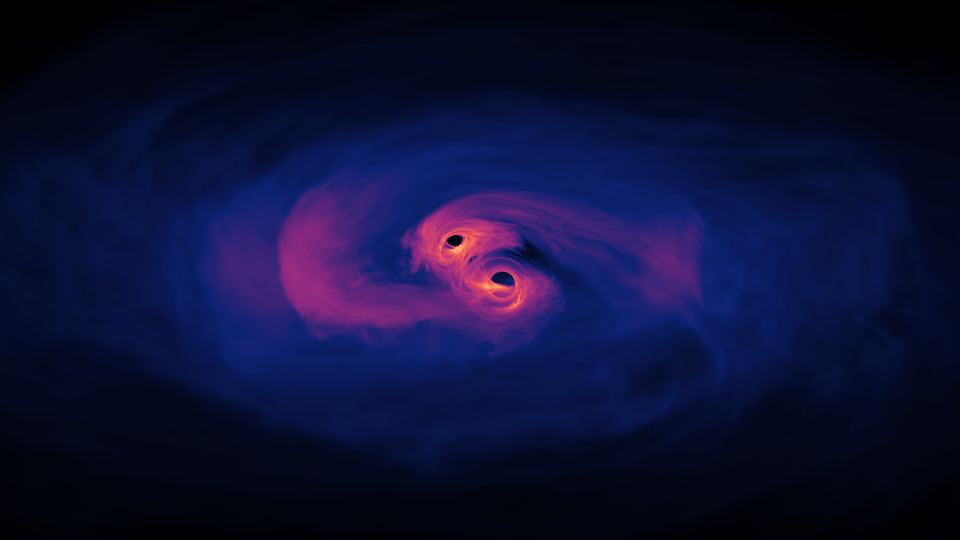

- when two galaxies merge, their black holes will preferentially sink toward the new mutual center, due to gravitational interactions between other masses.

- Interactions with gas and other normal matter will dominate for a time, leading to a relatively tight, short-period orbit for these black holes.

- In the final merger stages, lasting an estimated ~25 million years, gravitational waves will dominate, resulting in a scaled-up inspiral and merger scenario, albeit one that’s far beyond the reach of detectors like LIGO.

When two black holes merge together, their mutual inspiral causes the deformation of space, and their motion through that deformed space leads to the emission of gravitational radiation, which carries energy away from the black hole-black hole system and out to the Universe beyond. Given that we know of black holes that are many billions of times the mass of our Sun, the merger of black holes that are hundreds of millions of solar masses with multi-billion solar mass black holes is an inevitability.

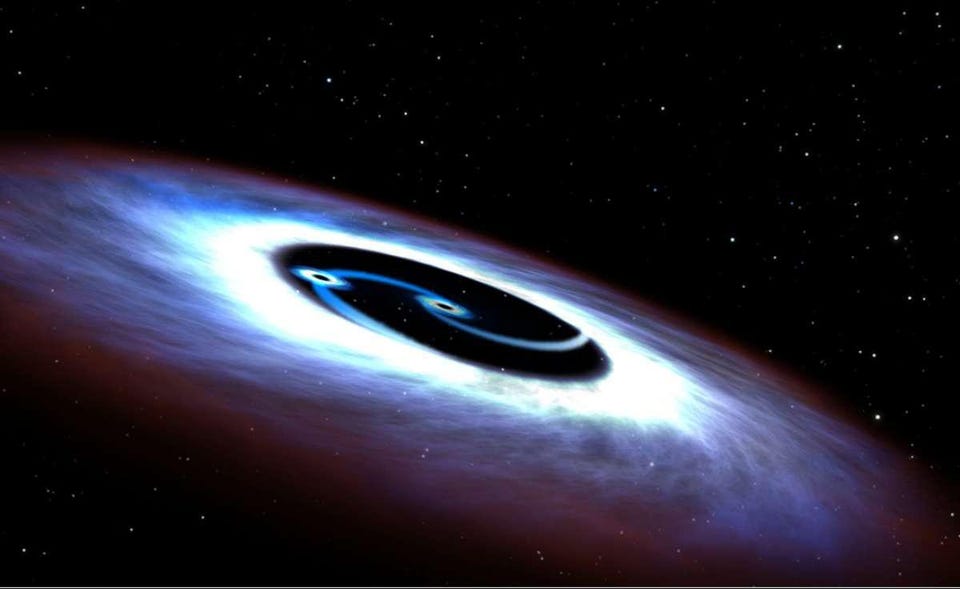

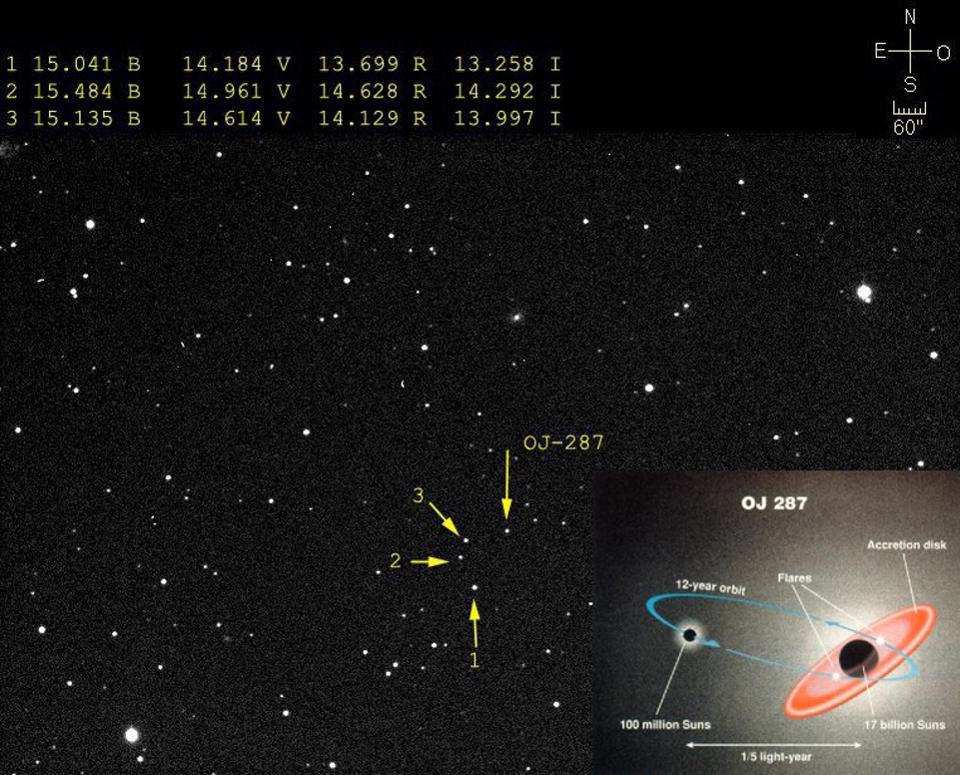

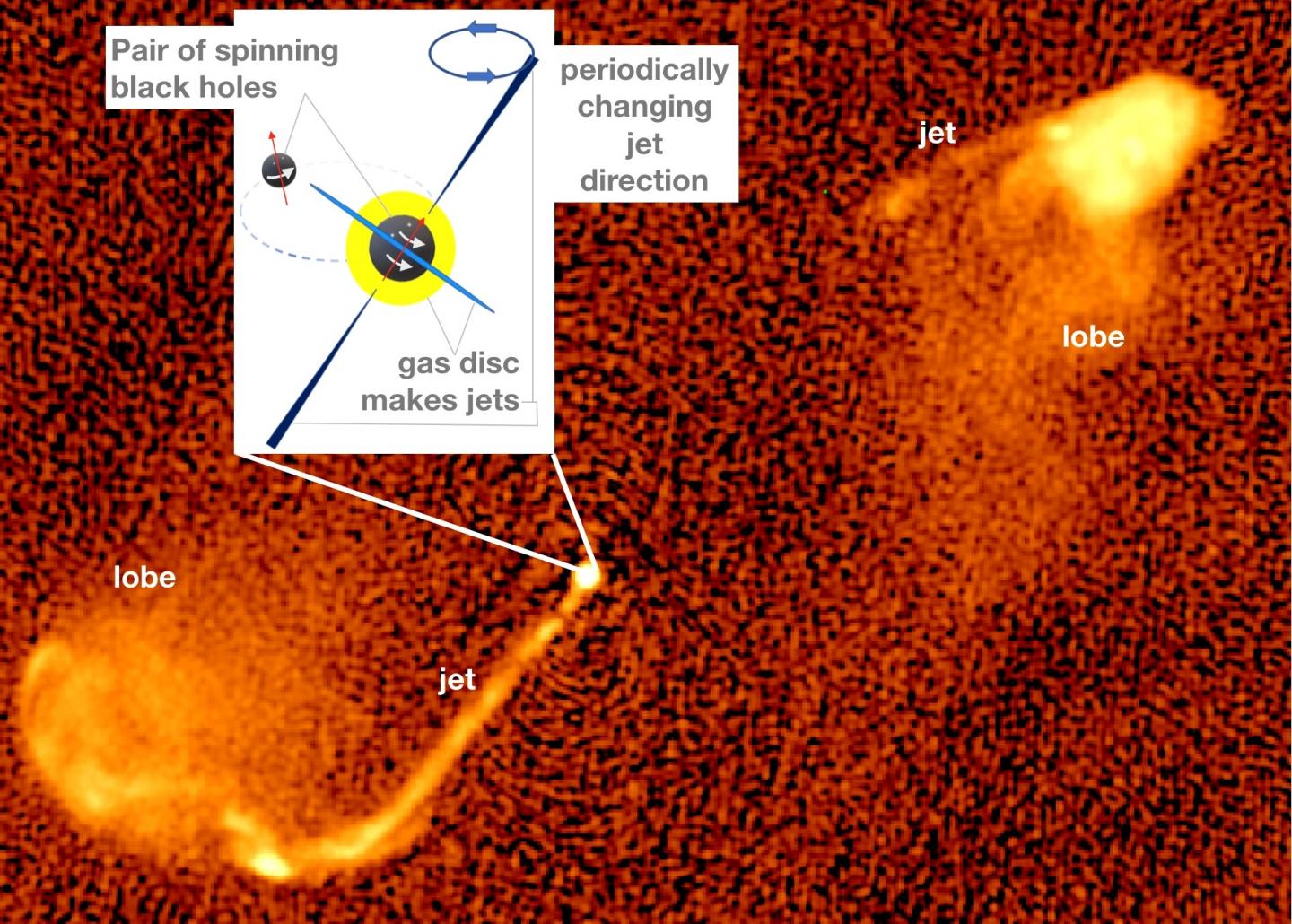

One system in particular, OJ 287, consists of a 150 million solar mass black hole in close orbit around an ~18 billion solar mass black hole. When they merge, ~3 × 1054 J of energy will be released over the final moments of this event, peaking right when the inspiral phase ends and the merger begins. The frequency will be all wrong for LIGO or even the future LISA array to detect, unfortunately. But in the lead-up to a merger, a different technique — one based on pulsar timing — could reveal a large merger like this, especially if the two masses were relatively close to one another in magnitude, after all.

The first supermassive black holes that are inspiraling, according to our best modern estimates, should be detectable this decade by advanced pulsar timing arrays such as NANOGrav, the European Pulsar Timing Array, and the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array. As these supermassive black holes inspiral, they should emit gravitational waves with a large enough amplitude and at a predictable, observable frequency that means — if we understand how to model the frequency and population of these supermassive binary black holes — the years left in the decade of the 2020s should lead to us detecting our very first one.

When we detected our first black hole-black hole merger, there was a brief time period lasting under 200 milliseconds where that merger produced more energy than all the stars in the Universe combined. If we can find a supermassive black hole merger where the smaller mass is more than 500-600 million solar masses, not only will it emit more energy than all the stars in the Universe for about a week, but it will become the most energetic event since the Big Bang, emitting more than ~1055 J over that time interval.

But it’s eminently plausible that there are many examples, particularly in rich galaxy clusters, where two black holes of billions or even tens-of-billions of solar masses will merge together, or have already merged together. In the nearby Coma Cluster for example, the two most massive galaxies are NGC 4889, with a 21 billion solar mass black hole, and NGC 4874, which looks to be more massive and possesses twice as many globular clusters, but with a black hole of a mass whose magnitude is presently unknown.

We won’t have merely gravitational waves to look for when two supermassive black hole-containing galaxies merge, either. They ought to emit telltale signs of electromagnetic radiation, particularly in the X-ray, which should offer the potential to study these mega-events in gravitational waves and electromagnetic signals simultaneously, even before they merge. With ESA’s Athena and, down the road, NASA’s Lynx potentially coming to augment our X-ray astronomy arsenal, we might finally discover the prototypical example of what promises to be the Universe’s most energetic event of all.

One of the most remarkable facts about merging black holes is that the maximum rate of emitted gravitational wave energy isn’t dependent on their mass at all, but rather is determined by the fundamental constants of the Universe. The heavier your black holes are, the more energy they emit, but the inspiral phase occurs over a longer period of time, rather than very briefly. They should still represent the most energetic events in all the Universe, however, as it’s the very end of the inspiral and the specific “event” of the merger phase where the greatest magnitude of energy is released. Even for these supermassive behemoths, we’re talking no more than seconds for the largest amounts of energy to be emitted.

With an ever-improving suite of instruments, detectors, and new techniques, the first hints of a supermassive binary black hole merger might appear later this decade, which would be an incredible development for gravitational wave astronomy, a science that only saw its first success fewer than 8 years ago. Supermassive binary black hole mergers are, undoubtedly, the most energetic single event in the entire post-Big Bang Universe. For the first time, they may be finally within our detectable reach.