Movie theater economics: If you love cinemas, buy the damn popcorn

- On average, movie theaters make more from concessions than they do from ticket sales.

- That’s largely because, thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, theaters have to share a portion of ticket sales with distributors.

- Although theaters have suffered heavily at the hands of streaming services and the COVID-19 pandemic, they still have tricks up their sleeves to attract new customers.

In order to make money, movie theaters must do more than show entertaining movies. They also have to differentiate themselves from their competitors who are generally showing the same movies. As such, it’s no surprise that cinemas have evolved at a rapid clip, developing from nickelodeons (cheap but highly social venues that showed films in exchange for a nickel) into picture palaces (lavishly decorated, air-conditioned opera houses that showed movies instead of operas) and into the high-tech theaters we frequent today.

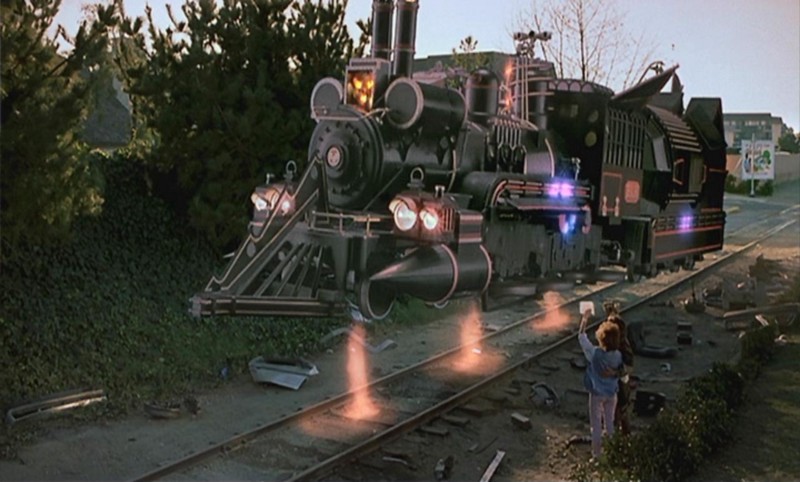

All of these iterations have one thing in common: the underlying conviction that a cinema is not just a place where you can watch movies, but also an integral component of the movie-watching experience itself. You hear this sentiment a lot these days, now that movie theaters are in financial trouble. Famous actors and directors often argue that their work is meant to be watched on a huge screen, not a small one; in a dark room filled with strangers, not at your house; and all while eating popcorn and drinking Coke, bought at the concession stand, not the supermarket.

Movie theaters have long capitalized on this highly marketable image. Unfortunately, it may no longer be enough to keep their current business models afloat. Mounting competition from streaming services like Netflix and Disney+, not to mention the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, have called the survival of movie theaters into question. But while many onlookers remain pessimistic, some cinemas — especially the independent ones — still have a few tricks up their sleeves.

The business of movie theaters

Under the studio system, which lasted from the 1920s until the 1950s, every movie theater in the U.S. was owned by one of five companies: MGM, Warner Bros., Paramount, Fox, and RKO. These companies, also known as the Big Five, controlled all aspects of the filmmaking process: They hired the screenwriters, shot the scripts, edited the footage, distributed the reels, and exhibited the final cuts in front of paying audiences.

The foundation of this system came crumbling down in 1948 when the U.S. Supreme Court, looking to control the Big Five’s market power, decided to separate the production and distribution of movies from their showing. Today, if a theater chain wants to screen a movie, they have to share a percentage of the box office with its distributor. That percentage lies between 25 and 60 percent, and varies depending on the popularity of the movie, the number of days it will be screened, and the bargaining power of the theater.

Let’s take a closer look at the balance sheets of a specific chain, AMC. In the first quarter of 2022, the biggest chain in the U.S. — as well as the world — reported a total revenue of $785.7 million, a substantial increase from the previous year’s $148.3 million. According to the company’s earnings report, 56% of total revenue came from ticket sales, 32% came from concessions, and 12% from “other theatre,” a category that includes things like on-screen advertising, rentals, gift card fees, and arcade games.

These numbers suggest AMC relies on ticket sales above all else. However, this is not necessarily the case. While the chain earned significantly more money screening movies than it did selling concessions, it should be noted that the cost of screening movies was also a lot higher than the cost of producing and selling concessions. (According to earnings reports, the mark-up for concessions exceeds 400 percent, while the markup for ticket sales barely hits 150 percent.) It’s often said that chains use ticket sales to break even and concessions to turn a profit, and AMC’s earning reports lend credibility to this statement.

While chains like AMC and Regal make up the majority of the market, they’re not the only type of movie theater out there. Assessing independent theaters is a bit more difficult, as many do not publicize their earnings. That said, the Independent Cinema Office estimates small cinemas (3 screens or less) make $544,000 each year on ticket sales and $113,000 on concessions. They appear to enjoy a substantially higher markup on tickets, perhaps because they have more bargaining power over small-time distributors.

Strategies to survive and thrive

The past couple of years have been rough on movie theaters. The COVID-19 pandemic temporarily paused the production of new films, including highly anticipated blockbusters. When cinemas weren’t under government order to remain closed, a large portion of moviegoers stayed home for fear of getting sick. Worse, the advent of streaming has completely overhauled the film industry, with studios opting to release films like Black Widow and Luca simultaneously or exclusively on their own platforms.

Although their losses are not as severe as they were a year ago, at the height of the pandemic, movie theaters are actively trying out new and creative tactics to attract customers. Big chains are investing vast sums of money in state-of-the-art technology. In April, AMC announced that it would be spending $250 million to install laser projectors from the tech company Cinionic in 3,500 of its U.S. locations. Cinionic’s projectors are said to provide crisper images than standard digital projectors.

Laser projectors are poised to enhance the movie-viewing experience just as 3D and IMAX have done before. Also worth noting is the degree to which theaters are looking to studios and directors who make big spectacles that, due to their extensive use of special effects, look more impressive in a cinema than they do on a laptop or smartphone. For example, movies produced by Marvel or Lucasfilm come to mind, as does the 2009 hit Avatar and its upcoming sequel.

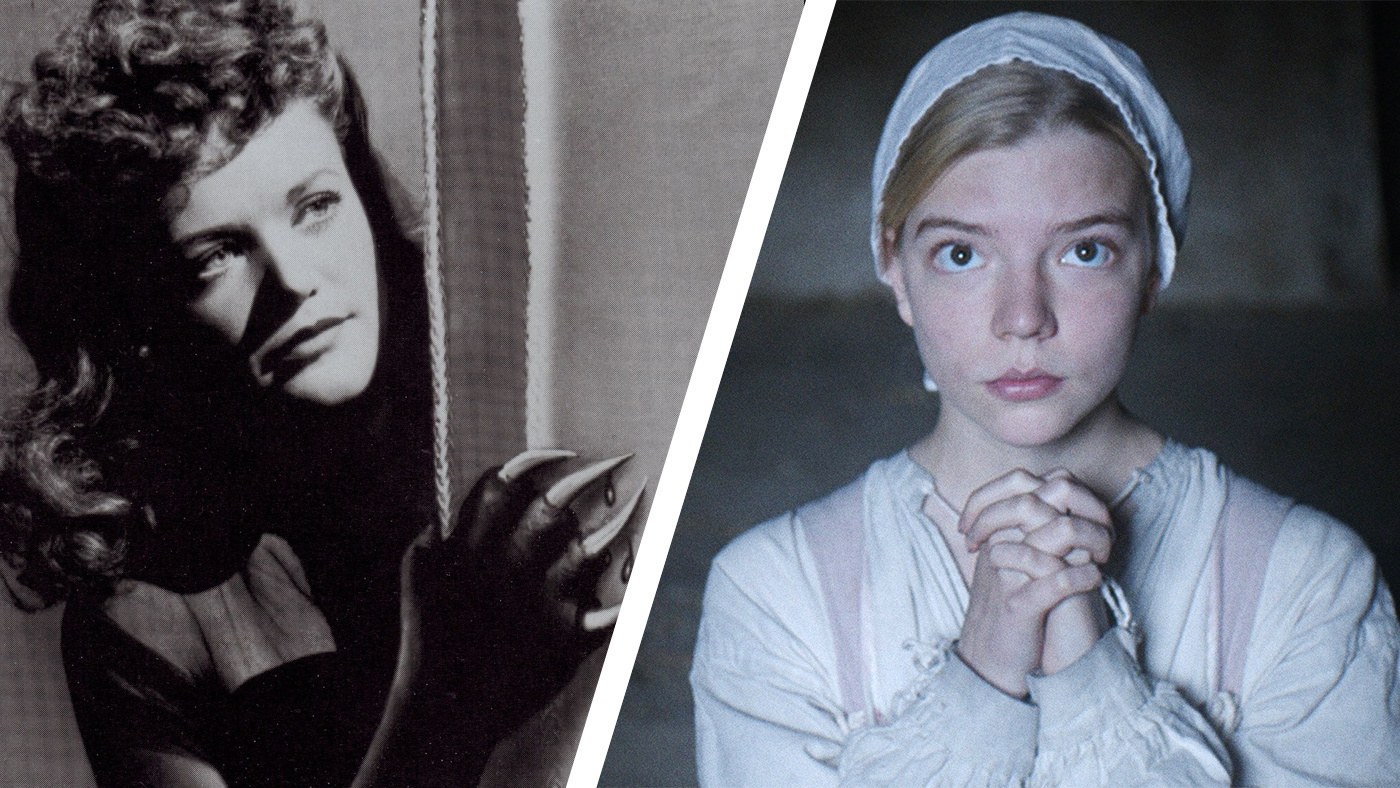

Aside from investing in technology, cinemas are doubling down on marketing. In September of last year, AMC launched its first-ever ad campaign. (Directed by the Oscar nominated cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and starring actress Nicole Kidman, the campaign was produced for $25 million.) In previous decades, cinema chains were able to rely on studios, who — having their eggs in the same basket — did most of the marketing for them. Now that studios are prioritizing streaming, though, theaters have to start looking out for themselves.

Smaller theaters can’t afford to pre-order the latest technology. What they can do is use social media to target niche audiences and build communities around their venues. There are now cinemas organizing knitting clubs, meditation sessions, and date nights with margaritas (moving beyond reclining seats, some venues sport “loveseats” for couples).

These initiatives may not be as fancy as what people would have seen inside the picture palaces of old, but they capitalize on the same social and experiential qualities of the moviegoing experience — qualities that have defined movie theaters since their inception.