Why John Stuart Mill was a capitalist

Many of us support certain ideas as a matter of habit. We know that we like democracy, freedom, and capitalism, but don’t know why. Today, in a world where meaningful debate between opposing sides is increasingly hard to come by, it is vital that we try to understand why people who disagree with us think the way they do.

Today, we would like to show you why one of the leading minds of Victorian England supported capitalism and how his reasoning still resonates today.

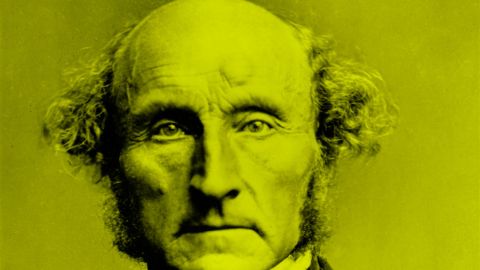

Who was John Stuart Mill?

John Stuart Mill was a 19th century English philosopher who is best known for his work in utilitarianism and classical liberalism. A masterful political philosopher, he was one of the few members of his field also to be elected to office.

While his ideas on economics shifted over the course of his life, he is still frequently cited by those who wish to support deregulation and free markets.

Why was Mill a capitalist?

In his book On Liberty, Mill argues that an atmosphere of freedom is not only the best for humanity as a whole, but also for the development of individuals as autonomous, fully developed people. It is only by letting people be free and make choices that they can grow as people, he argued.

To promote that end, he argues that we must allow such things as the freedom of speech, press, thought, and lifestyle to everyone. This will allow people to explore new ideas and find the activities and ways of living that would enable them to flourish.

That ability to flourish was his principal criteria for judging a society, as “what more or better can be said of any condition of human affairs, than that it brings human beings themselves nearer to the best thing they can be?”

He did think we need laws though and invited the “harm principle” to help us examine which regulations on our behavior were justified. The principle says that only activities which should be regulated are those which negatively affect others.

This principle opens up most actions that we make in public to potential regulation, but he argues that we should only prohibit activities that cause significant harm to other people; such as assault or theft.

How does this philosophy relate to business?

Mill also argues across his works that letting people figure out the best way to do business is akin to making them figure out what the best way of life for themselves is and similarly fosters their development as autonomous individuals.

If a business were overly regulated, then the people working in it would no longer be mentally stimulated by problems to solve. Instead, they would just be following orders like dull machines and could not use their work to grow as people. To prevent this, he encourages us to leave people free to carry out their own business as much as possible.

Similarly, while business is a public activity, and therefore something the state could regulate if the need arose, the leading economic theories of the day said that free markets gave the best financial results. Mill, ever the consequentialist, explains that this is reason enough to leave business alone.

What if the state could do it better than the market in some cases?

Even in instances where the state could do a better job than the market in providing a non-essential service, Mill suggests that we let the market handle it anyway for the benefits it offers to individuals explained above.

He also feels that giving the state power it doesn’t need poses a danger. He notes that in a world where the state handles all economic aspects, even if it did well, “nothing to which the bureaucracy is really adverse can be done at all.” He says this would be dangerous for liberty, even if lip service was given to the other freedoms we enjoy.

In cases of essential goods and services, like education, Mill is open to the state providing such services though he favors the state working in competition with the market. He justifies this support for interventionism by showing how the need for some goods is great enough to warrant state action, especially in cases when they are needed to help foster personal development.

So, how moderate can we say he was or wasn’t?

Mill was moderate in his political stances overall. While he opposed most intervention in the economy, he was not so ideologically bound as to oppose it when utility demanded it.

For example, he was open to the idea of taxing vices, requiring record keeping for sales of dangerous substances, and even having the government step in to supply services, such as education, when the market would fail.

However, given his desire to maximize the liberty each person enjoyed he encouraged these interventions to be kept to a minimum and for each issue to be considered on a case by case basis.

Did he have anything good to say about other economic systems?

Like many thinkers who lived through the Victorian era, he became increasingly interested in social welfare later in his life after witnessing the inability of charity to solve major social problems. In later editions of his textbooks on political economy, he also remarked that no laws of economics forbade socially owned enterprises from being profitable as part of his leftward drift.

He was also entirely in favor of worker cooperatives, in which the workers own the means of production and manage the workplace democratically. However, he felt that this was a system for better, more cooperative people as yet unborn.

J.S Mill remains one of the most influential philosophers of the 19th century. While he changed his mind on many things over the course of his life, his arguments for why free markets would promote human development are still worth considering in a world where civil discussion of such issues is rarer and rarer.