10 things Eastern thinkers discovered centuries before the West

In the West, we tend to suppose that all of the best scientific discoveries happened in Europe or North America. This is inaccurate, for while Europe was in the dark ages the Islamic Caliphates were enjoying a golden age of scientific progress, cultural achievements, and economic growth.

This golden age lasted almost 700 years and influenced every field of scientific discovery. It was promoted by lots of funding for the arts and sciences and refinements in the scientific method combined with better communications between distant scientists.

The golden age ended after the destruction of Bagdad by the Mongols and a general turning of interest away from science between the 13th and 14th centuries. Right as the Islamic Golden Age ended, the Renaissance began in Europe. With the help of Greek and Roman texts the Islamic world preserved, Europe would ultimately reach the heights of Arabian science and later surpass it.

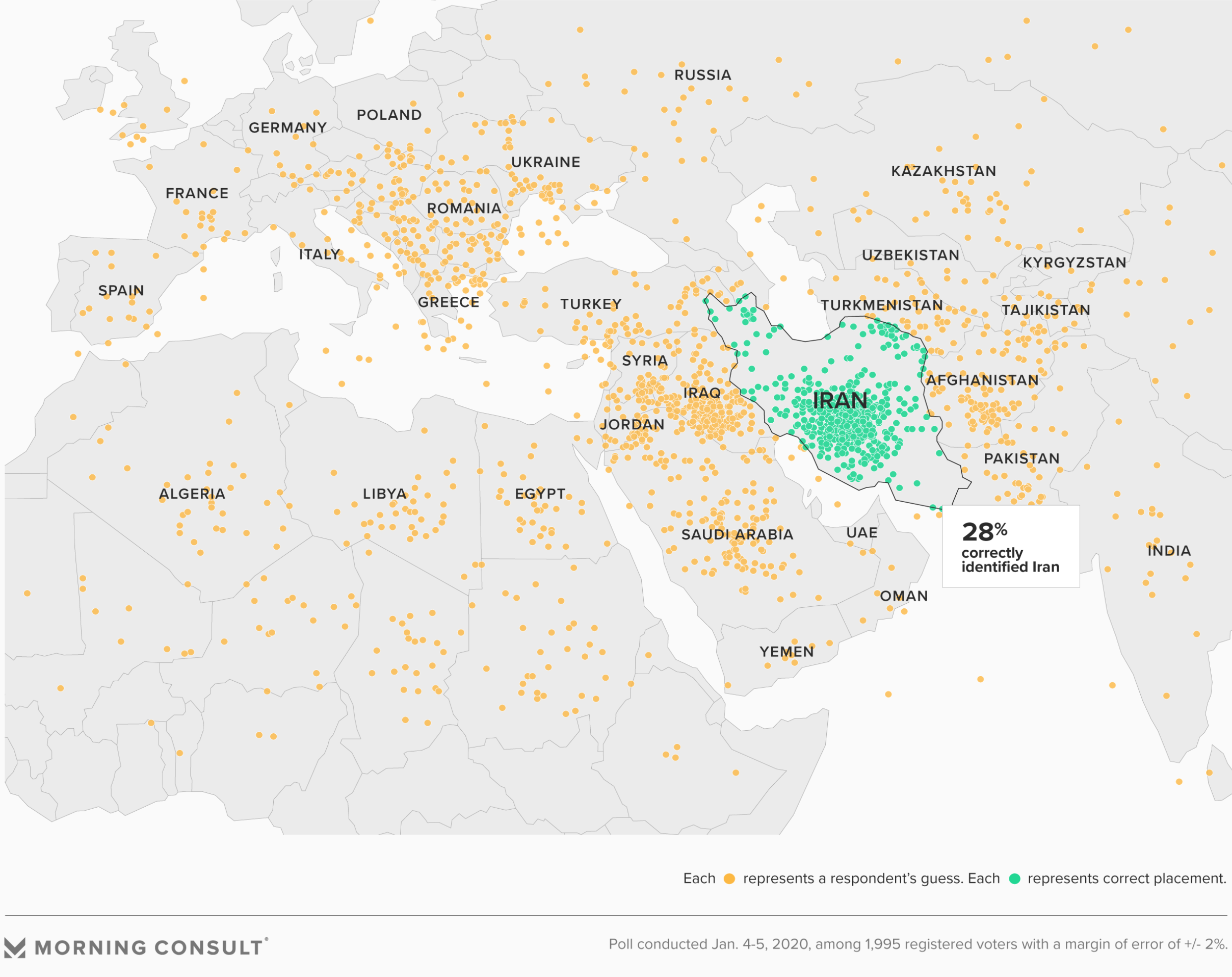

It didn’t happen overnight though, here are ten things the Islamic world discovered first and how long it took the West to figure it out afterward. Many dates and details are taken from this infographic at informationisbeautiful.net.

The Heliocentric Model

Attempts to explain solar eclipses prompted the first heliocentric models. (Getty Images)

While the Ancient Greeks knew the Earth went around the sun, the idea that the Earth was the center of the universe come to prominence during the Roman Empire. This worldview was dominant until the 17th century.

However, during the golden age, several Arabic astronomers began to suggest that the sun was the center of the solar system. In the early 11th century the Iranian Al-Sijzi argued that the Earth rotated on its axis and his contemporary Alhazen wrote a book criticizing parts of the Ptolemaic view of the universe.

It wasn’t until 1453 that Copernicus made the same suggestion in Europe, using a model of planetary motion that was similar to one that the Islamic world had already developed.

Zero

In 813 a Persian mathematician named Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī was the first Islamic scholar to use Hindu numerals in his work, including zero. He also explained that a person should put a zero in places with no value, such as the tens place in the number 101, to “keep the rows.” Given how cumbersome previous methods of expressing zero were in Arabic, this was a huge step forward for mathematics.

It was another 150 years before Europe used what we now call Arabic numerals. They first appeared in Codex Vigilanus, a collection of Church documents. However, the zero was not included. Getting a number to represent nothing, a major conceptual issue for many mathematicians of the day, would take a few centuries more.

Evolution

(Getty Images)

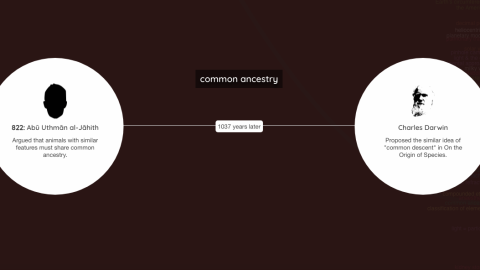

While some ancient Greek thinkers supposed that one species could descend from another, Aristotelian thought rejected this notion and western thinkers mostly gave up on the idea of evolution and natural selection for two thousand years.

In the Middle East, Al-Jahiz broke from Aristotle when he suggested that animals adapted to their environments in 822 C.E. His argument hints at an understanding of natural selection that the West would not rediscover for 980 years; when Jean-Baptiste Lamarck would suggest similar ideas in France.

Programmable Machines

It wasn’t quite a laptop, but incredible none the less.

In The Book of Ingenious Devices, written by three brothers known collectively as Banū Mūsā in 850, described one hundred fantastic machines.One of the many wonders in the book is a robotic flute player that utilizes steam to produce notes. If the device was adjusted properly, specific songs could be played. This is the first known description of a programmable machine.

The west took 954 years to catch up, in the form of a programmable loom that used punch cards to determine which weaving patterns would be automatically carried out.

Attempts at Flight

The joys of flight brought to you in part by Caliphate thinkers in Spain.

While humanity has always longed to fly, attempts for the first several thousand years of our existence were either foolhardy or deadly. This didn’t deter Abbas ibn Firnas, who in 852 created two large wings for himself and leaped from a tower in Islamic Spain. He forgot a tail, however, and hurt his back upon landing.

A similar attempt would be made in the Christian part of Europe in the 11th century when a monk named Eilmer of Malmesbury did precisely the same thing, including leaving out a tail and enduring a hard landing.

Clinical Trials

Homeopathy, debunkable since the 10th century.

While it seems evident to us now that control groups are needed in science, this concept took centuries to establish. Like everything else on this list, the East did it first.

Persian physician Al-Razi, who has many discoveries to his name, also has the honor of inventing the clinical trial in medicine. His test was simple but bold. When treating a meningitis outbreak, he had the good sense to record the progress of those treated with bloodletting and those without and compared the results later to improve future treatments.

In the West, it would be 850 years until similar concepts found their way into medicine when James Lind devised an experiment to find a diet that would prevent scurvy.

The Laws of Refraction

Experiments with lenses six hundred years late to the party. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

While the law of refraction, Snell’s Law, is named after Willebrord Snellius, it was first accurately described by the Persian scientist Ibn Sahl in 984 and Alhazen very nearly formalized it in 1021, but he stopped just short of this.

Snell would not devise his law until 1621 and didn’t publish it during his lifetime. Rene’ Descartes would also discover it himself in 1631.

Anesthesia

A group of doctors in Boston poses for a photo demonstrating their first use of anesthesia. They are a little behind Middle Eastern surgeons. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

While human beings have sought out painkillers for as long as we have been around, the use of drugs for general anesthesia during surgery was pioneered by Al-Zahrawi in the 10th century. He describes in his book, Method of Medicine, of successfully using a sponge filled with narcotics placed under the noise of the patient to prevent pain during operations.

In Europe, Ramon Lull would discover ether in the 13th century. However, nobody got the bright idea to use it during surgery until 1842, almost 900 long, painful, years after Al-Zahrawi wrote his book.

The Moon Illusion

A “supermoon” rises over London. (Photo by Chris J Ratcliffe/Getty Images)

Have you ever noticed that the moon looks much larger when it is on the horizon than it does when it is in the center of the sky? Have you ever wondered why that is? While many proposals have been put forward, it is the suggestion of Alhazen that has gained the most traction.

Alhazen explained in his Book of Optics that when the moon is on the horizon, our brains use objects on the ground to try and establish how far away the moon is and thus how large it must be. When it is directly overhead, however, there is nothing to establish distance nearby and our brains assume it is smaller than it is.

Europe would stumble upon the same idea 265 years later when Roger Bacon expanded on Alhazen’s work.

The Milky Way

Persian astronomer Al-Biruni was the first to determine that the Milky Way is a collection of individual stars and not some single nebulous object as suggested by Aristotle. This idea caught on in Arabian astronomy and was also held by several other prominent astronomers.

In Europe, Galileo would reach the same conclusion 500 years later using his telescope. It is worth noting that while the Arabian astronomers realized that the Milky Way was made up of stars, Galileo was the one who proved it.