Researchers Discover Monkeys Have a Speech-Ready Vocal Tract

No one has ever heard a non-human primate speak, at least not a human language. No one has been able to teach one to do so, either. Back in 1969, a team of researchers from Yale, using technology available to them at the time, concluded that most primates, rhesus monkeys specifically, “lack the output mechanism necessary for the production of human speech.” A study just released in Science Advances comes to a very different conclusion: ““A monkey’s vocal tract would be perfectly adequate to produce hundreds, thousands of words,” says cognitive scientist W. Tecumseh Fitch, one of the study’s co-authors, speaking with the New York Times in their article on the study. Or as the new study’s title succinctly puts it, “Monkey Vocal Tracts Are Speech-Ready.”

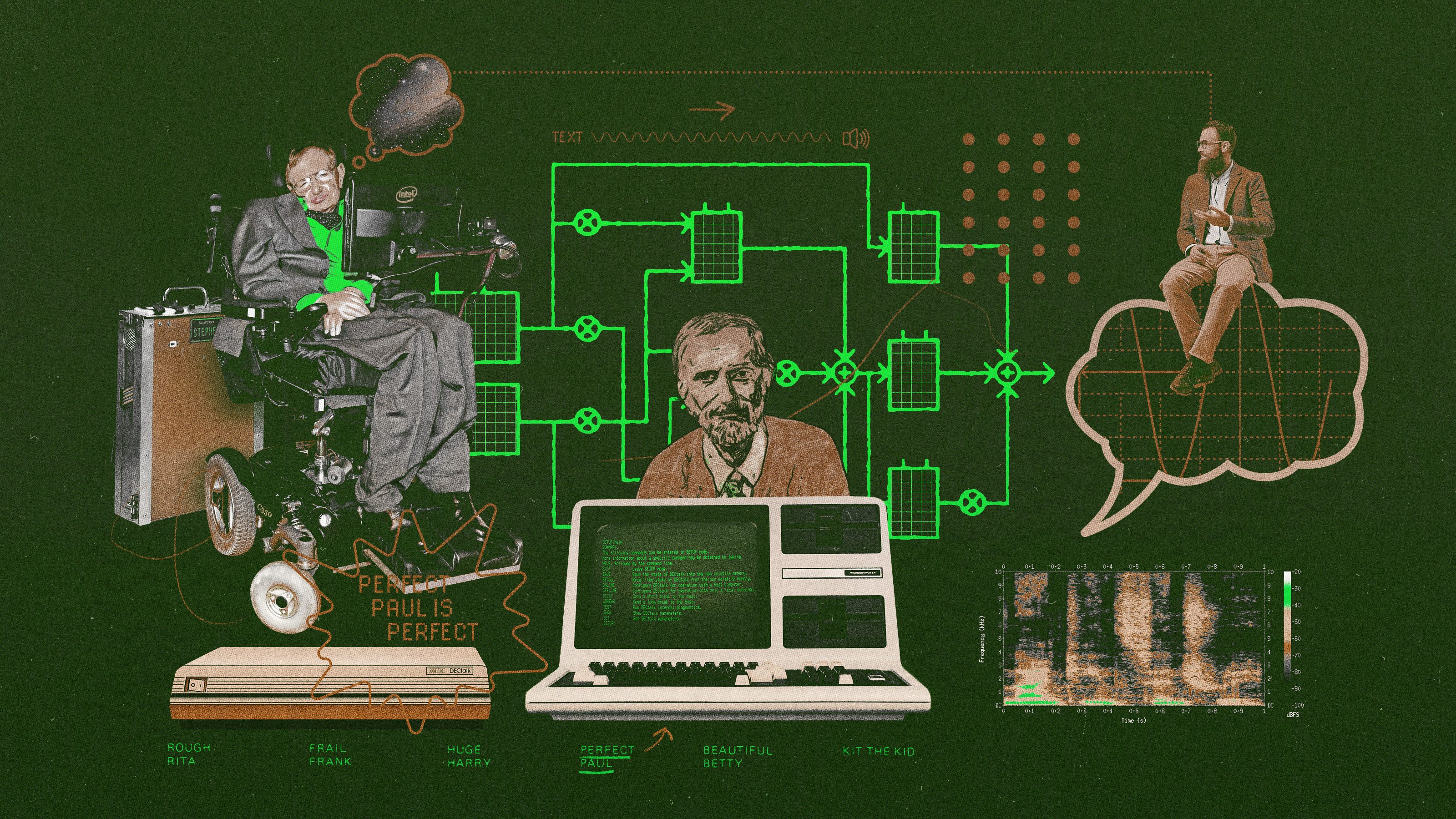

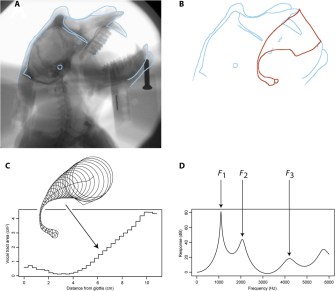

Research techniques have come a long way from the late 60s, when the Yale team created a plaster mold of a dead monkey’s vocal tract and applied various acoustic formulas to try and discern the sounds it was capable of making. The new study utilized x-ray videos to observe the mechanics Emiliano, a rhesus macaque monkey, used to produce vocal sounds. (Those are rhesus macaque monkeys sharing secrets above.) After giving him a barium-based contrast agent, they were able to image the coos and grunts he made when offered fruit. They also captured Emiliano swallowing his yummies to measure the maximum width his throat could attain. 99 stills were extracted from the videos, and the researchers plotted the shape of the vocal tract in each picture to generate a three-dimensional computer model. By pushing virtual air through the model, they were able to discern the sounds each shape could produce.

And there were a lot of possible sounds, including the five key vowel sounds contained in the words “bit,” “bet,” “bat,” “but,” and “bought,” according to Fitch. People for whom these sounds were played were mostly able to recognize them, and audio software even allowed the researchers to assemble the Emiliano’s utterances into a marriage proposal.

Still, Philip H. Lieberman, one of the Yale study’s authors, pointed out to the Times that one of he most important human vowel sounds— the long “e” — is notably absent from the test subjects’ repertoire. But speech scientist Anna Barney told the Times she’s impressed, and that the sounds the monkeys produced are a good starting point for speech, with one big caveat: the study doesn’t demonstrate a capacity for consonants. “What they’ve shown is that monkeys are vowel-ready, not speech-ready.”

So, why don’t non-human primates talk to us? We know they’re smart. Chimpanzees may be better than we are at game theory, and capuchin monkeys understand human money, something that can’t even be said of most human teenagers.

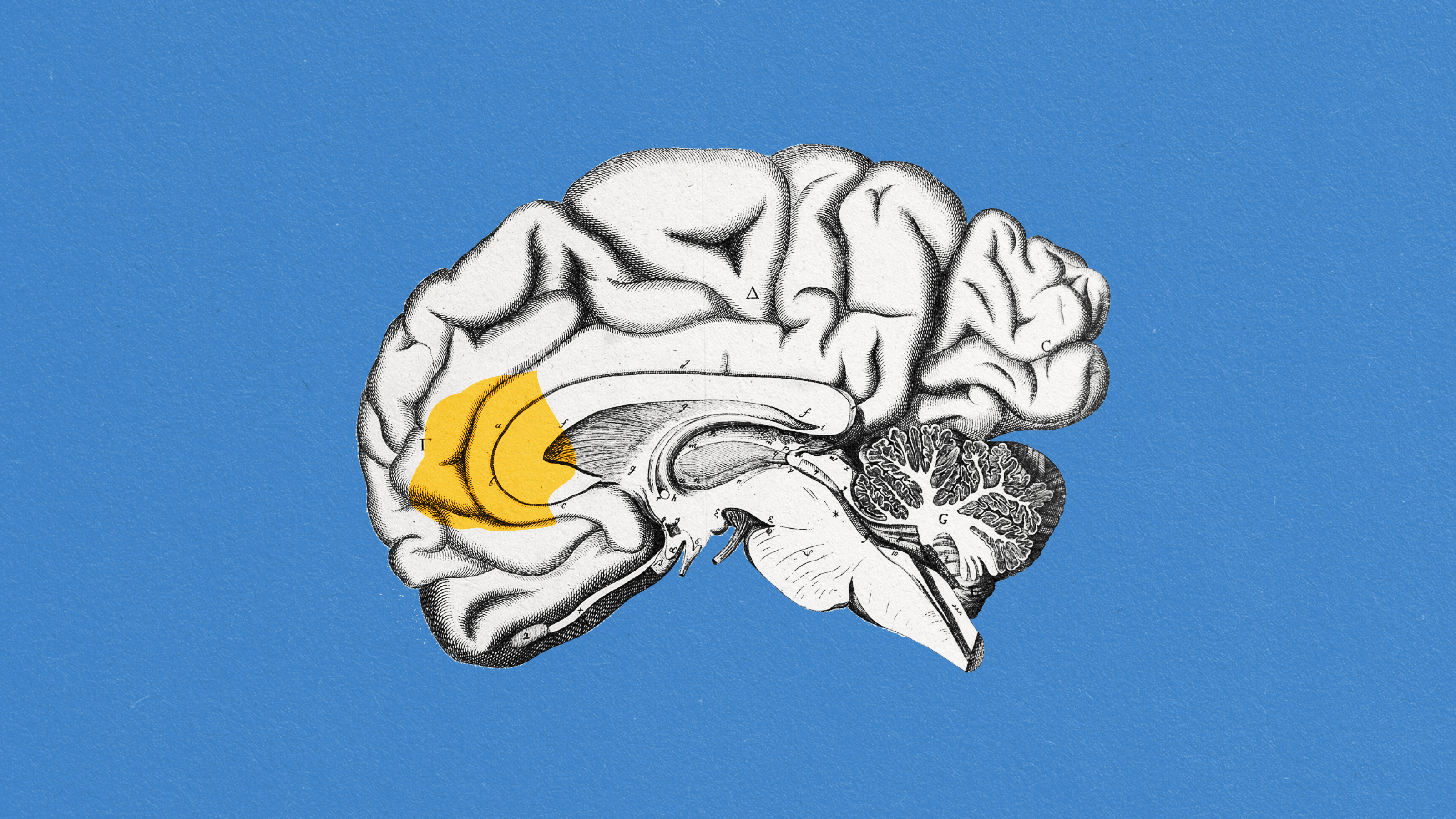

Though the new study didn’t examine the reason monkeys don’t talk, another one of its authors, neuroscientist Asif A. Ghazanfar suspects, “If they had the brain, they could produce intelligible speech.” Speech is, after all, a complicated process involving perfectly synchronized muscle movements and airflow. Human brains may have unique wiring that allows us to learn words when we’re young, and we have a special set of nerves that give us highly developed motor control of our vocal tracts.

Tantalizingly, not everyone agrees other primates can’t learn to speak. Adriano Lameira, recently taught an orangutan named Rocky to imitate human speech.

Lamiera tells New Scientist, ““There’s a growing body of evidence from all great ape species that there are few neural limitations. Our closest relatives can vocally learn new vowel-like and consonant-like calls, both in the wild and in captivity.”