Justice Thomas’s Silence (Redux): Response to a Reader

On Monday, I suggested that Justice Thomas might build on his first moment of non-silence in seven years. “If he wants to demonstrate that he takes his judicial role seriously with landmark decisions looming,” I wrote, “Justice Thomas should consider asking a question now and then” during Supreme Court oral arguments.

In response, a reader had this to say:

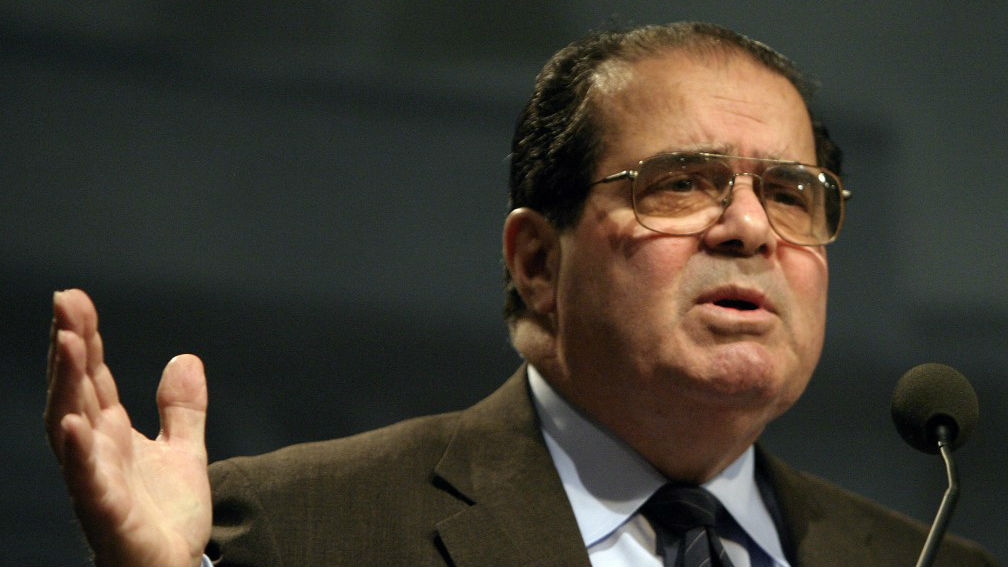

Hypatia501 offers an interesting take on a possible reason for Justice Thomas’s silence and makes an excellent point about the relative judicial talents of Justices Scalia and Thomas. Though his positions are just as far to the right (and maybe farther), Thomas has never said anything as offensively stupid as Scalia’s recent comparison between homosexuality and murder. And although Thomas is often regarded as a meek follower of the boisterous Scalia, the reality is very different. As Linda Greenhouse observed, looking at the landscape of the justices’ rulings in 2011, “in decisions that have split the court in any direction, Justices Scalia and Thomas have voted on opposite sides more often than they voted together.”

Yet I disagree with the reader that oral argument is just an opportunity for “bullying and grandstanding.” The sessions can be exciting, live, raw encounters where the ideas in the briefs are probed and prodded, not just rehearsed. Since the Court started publishing transcripts of the arguments on its website a few years ago, the media have begun quoting and sharing the exchanges with readers and viewers more regularly (how often do you hear the Brief of Respondent quoted on the nightly news?) and the intellectual exchange at the Court has entered the consciousness of many more Americans. These documents now serve as an important part of public justification and deliberation in our democracy. To have one of nine justices silent in those pages is problematic, both substantively and symbolically — especially since 2004, when the Court began to identify the justices by name in the transcripts.

And while his originalism is, as Hypatia501 suggests, surely less crass than Justice Scalia’s, Justice Thomas’s forays into legal history are spotty. Nowhere is his selective originalism more evident than in his absolutist position against benign racial preferences and in favor of a strictly colorblind interpretation of the Equal Protection Clause. These contentions have nothing to do with how the 14th Amendment was understood by its framers. Here is how I explain the history in a recent article in the Law Journal for Social Justice:

As Andrew Kull demonstrates in The Color-Blind Constitution (1992), there is no evidence that the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended to “require color blindness on the part of government.” In fact, there is ample evidence to the contrary. In 1865, members of Congress considered several proposed amendments that would have prohibited racial classifications altogether. One proposal, from Thaddeus Stevens, read as follows: “All national and State laws shall be equally applicable to every citizen, and no discrimination shall be made on account of race and color.” This proposal and similar ones were eventually rejected in favor of a looser, less specific, and less demanding standard authored by Congressman John Bingham of Ohio: “no state shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” This formulation became the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. Explicitly bypassing an amendment that would have banned racial distinctions outright, the 39th Congress decided against a principle of colorblindness in the Reconstruction Amendments.

If Justice Thomas were to re-read the history of the 14th Amendment, he might think differently about the issue at the heart of this spring’s important affirmative action case involving the race-conscious admissions policy at the University of Texas. He might not change his mind in the end, but there’s certainly enough complexity here to justify a question or two during oral argument.

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie