Why Mutually Assured Destruction Can No Longer Keep the World from Annihilation

At the height of the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) kept the two sides from taking the conflict nuclear. The idea behind MAD is that if both sides were to fight a full-scale war with nuclear weapons, there would be no winners and both would be mutually annihilated. This understanding has so far kept the world from erupting into another all-encompassing war but is it relevant in the modern context of international relations? Would the prospect of complete destruction to all sides keep us away from war with North Korea?

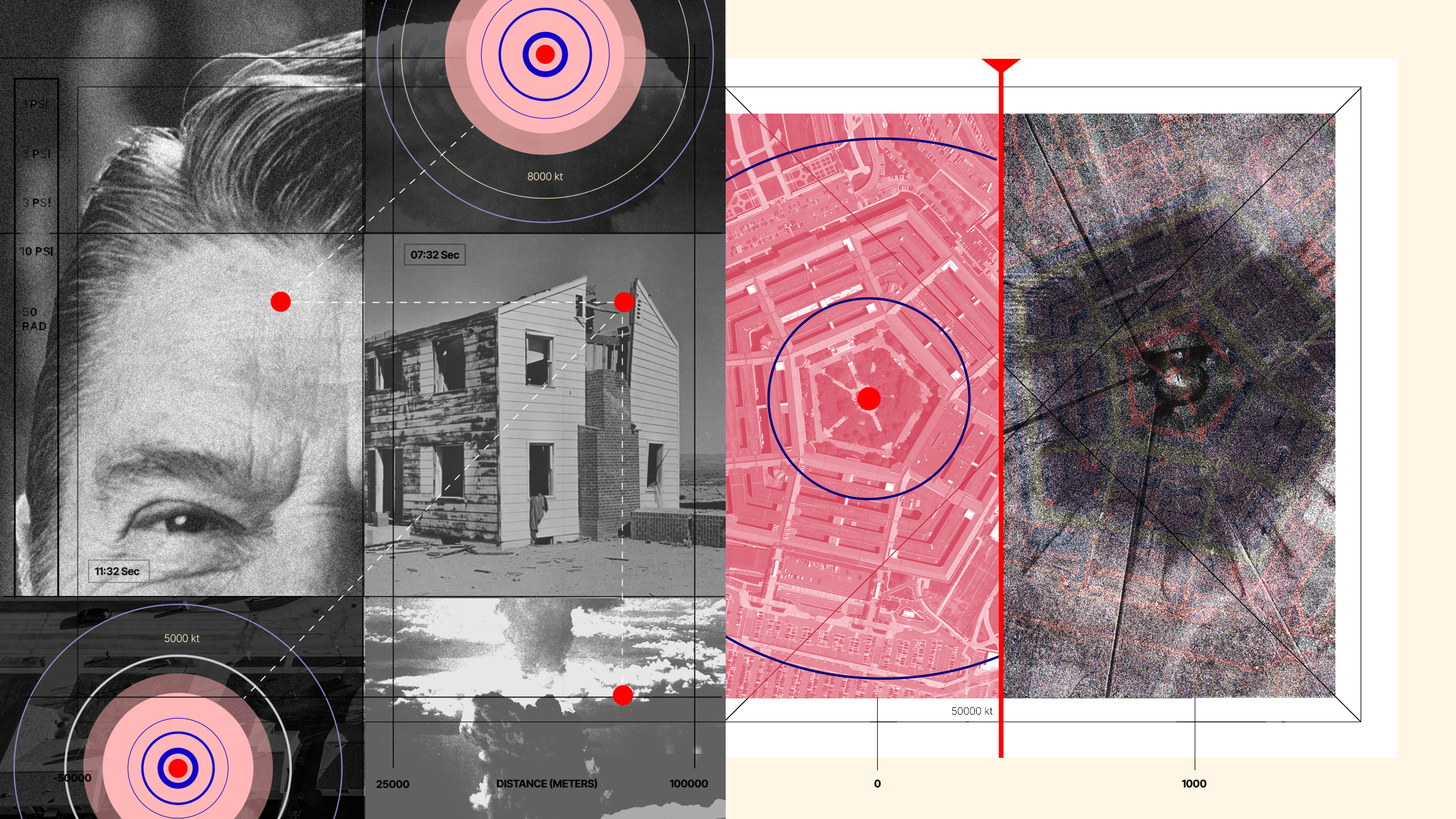

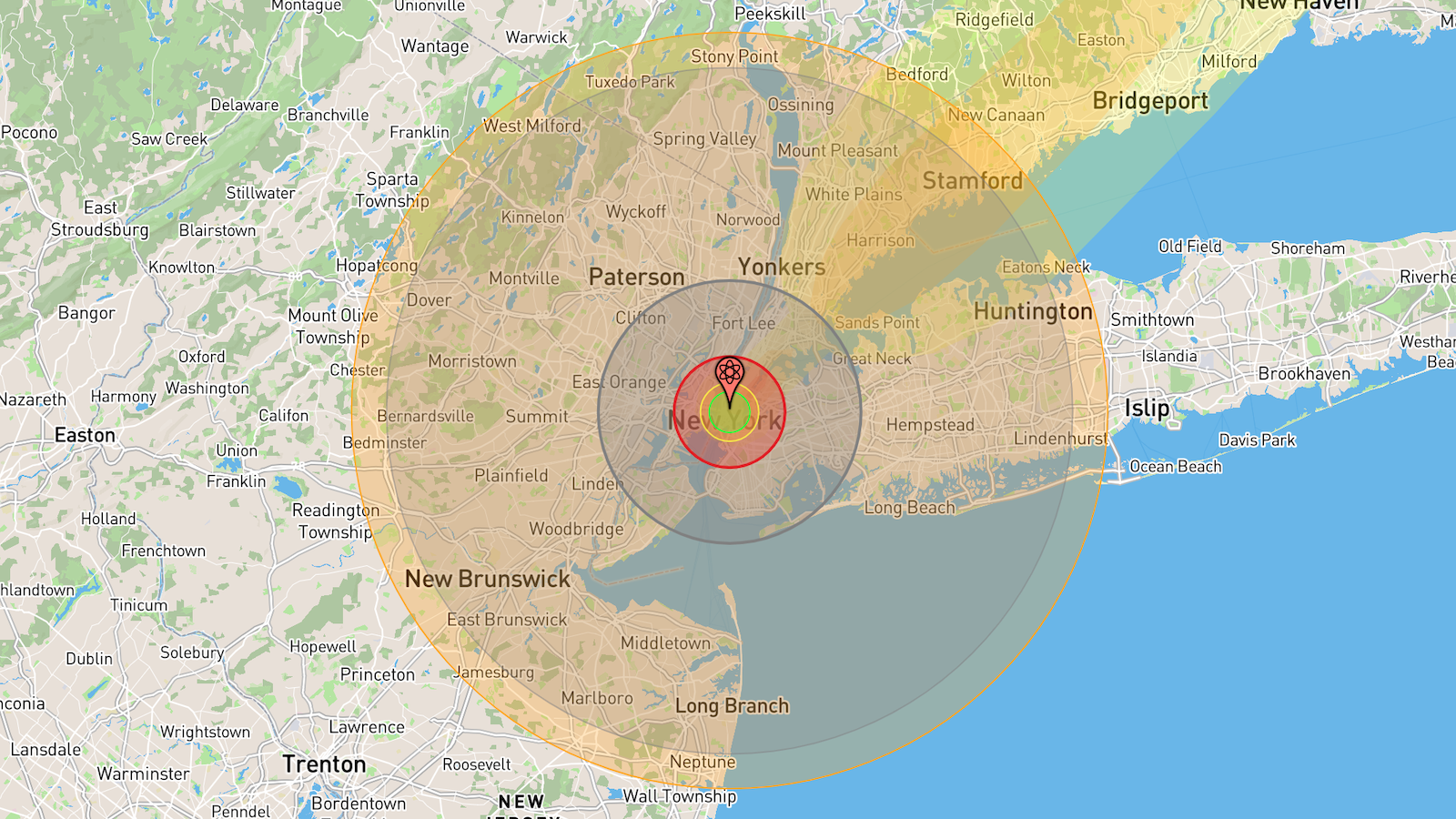

The idea behind MAD is based on the theory of deterrence, a military strategy which holds that the threat of annihilation would keep opponents at bay. If North Korea was to launch a first nuclear strike, it would surely perish in immediate retaliation strikes by the United States.

Thomas Schelling, an American foreign policy and national security expert, argued in his 1966 book “Arms and Influence” that modern military strategy must include coercion, intimidation and deterrence. The goal of attaining military victory is almost too simplistic in the current state of international affairs. You can influence another state by making it anticipate the violence your nation can inflict upon it.

US marines watch the mushroom cloud from an atomic explosion rise above the Yucca flats, Nevada during a 1945 US nuclear weapons test. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Judging by the lack of direct armed conflict between nuclear nations since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, it can be said that the idea of nuclear deterrence based on MAD has worked relatively well. But is this type of uneasy peace going to last?

One way nuclear nations confront each other without resorting to all-out mutual annihilation is through proxy wars and indirect confrontation, maintains the international relations theory of the stability-instability paradox. We are talking about wars in Korea, Vietnam, the Middle East, Nicaragua, Afghanistan and other hot spots around the world where the Soviet Union and the United States were able to push against each other’s ambitions by supporting already fighting sides rather than battling each other head on.

In the modern arena, Syria, Ukraine and North Korea present such a setup, with larger players jockeying for position and influence. As recent events have shown, these types of regional fights have a way of creating tensions where larger parties may rattle their sabers but generally prefer to disengage.

President Trump’s order to attack a Syrian airbase after an alleged chemical attack did not lead to further escalation with Russia, a staunch ally of the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. Neither did Russian President Putin’s use of so-called “little green men”– mercenaries or unofficial Russian military fighting in Ukraine for Russia’s interests, with Russia being able to maintain deniability of its involvement.

Russian paramilitary surround a Ukrainian military base on March 19, 2014 in Perevalnoe, Ukraine. (Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Cyberwarfare is another form of off-the-books conflict that has gained effectiveness and state support in new military doctrines. Russia’s attempts to influence the U.S. election in 2016 is a prime example of such an approach. Damage can be caused to institutions and morale of an opponent without firing a single shot.

While the competing nation states find other ways to wound their geopolitical opponents, deterrence theory may also not work if one of the players is not rational or will pursue goals that benefit from widespread destruction – for example, ISIS may use any nuclear weapon it gets a hold of to cause maximum damage and havoc.

In a 2010 film “Nuclear Tipping Point,” the legendary former secretary of state Henry Kissinger pointed out the limitations of deterrence in a world of suicide bombers:

“The classical notion of deterrence was that there was some consequences before which aggressors and evildoers would recoil. In a world of suicide bombers, that calculation doesn’t operate in any comparable way,” said Kissinger.

People watch a news report on North Korea’s first hydrogen bomb test at a railroad station in Seoul on January 6, 2016. (Photo credit: JUNG YEON-JE/AFP/Getty Images)

There have also been questions raised about the mental stability of both Kim Jong-un, the North Korean dictator and President Donald Trump. If people pushing the buttons are not acting rationally, deterrence may also not work.

Notably, the U.S. National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster has publicly doubted whether classical deterrence would have influence with Kim Jong Un because of the perceived irrationality of the regime.

“The classical deterrence theory, how does that apply to a regime like the regime in North Korea?” said McMaster in an appearance on “This Week” on ABC News. “A regime that engages in unspeakable brutality against its own people? A regime that poses a continuous threat to the its neighbors in the region and now may pose a threat, direct threat, to the United States with weapons of mass destruction? A regime that imprisons and murders anyone who seems to oppose that regime, including members of his own family, using sarin nerve gase (sic) — gas in a public airport?”

Author and President of a conservative think tankClifford May, writing in the Washington Post, sees leaders of both Iran and North Korea as being relatively immune to the doctrine of MAD.

“During the Cold War we relied on mutually assured destruction (MAD) to keep American and Soviet nukes in their silos, wrote May. Is that doctrine adequate to constrain Kim Jong-un, a dictator whose grasp on rationality is difficult to gauge? What happens if Iran’s next supreme leader believes that to bring about the return of the 12th Imam, the Shia messiah, requires an apocalypse? Bernard Lewis, the esteemed scholar of Islam, famously said that for those who hold such beliefs — former Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was among them — ‘MAD is not a deterrent, but an inducement.'”

He sees extreme sanctions and non-nuclear military options as being necessary to influence the behavior of such recalcitrant adversaries.

An explosion rocks Syrian city of Kobani during a reported suicide car bomb attack by the militants of Islamic State (ISIS) group on a People’s Protection Unit (YPG) position in the city center of Kobani, as seen from the outskirts of Suruc, on the Turkey-Syria border, October 20, 2014 in Sanliurfa province, Turkey. (Photo by Gokhan Sahin/Getty Images)

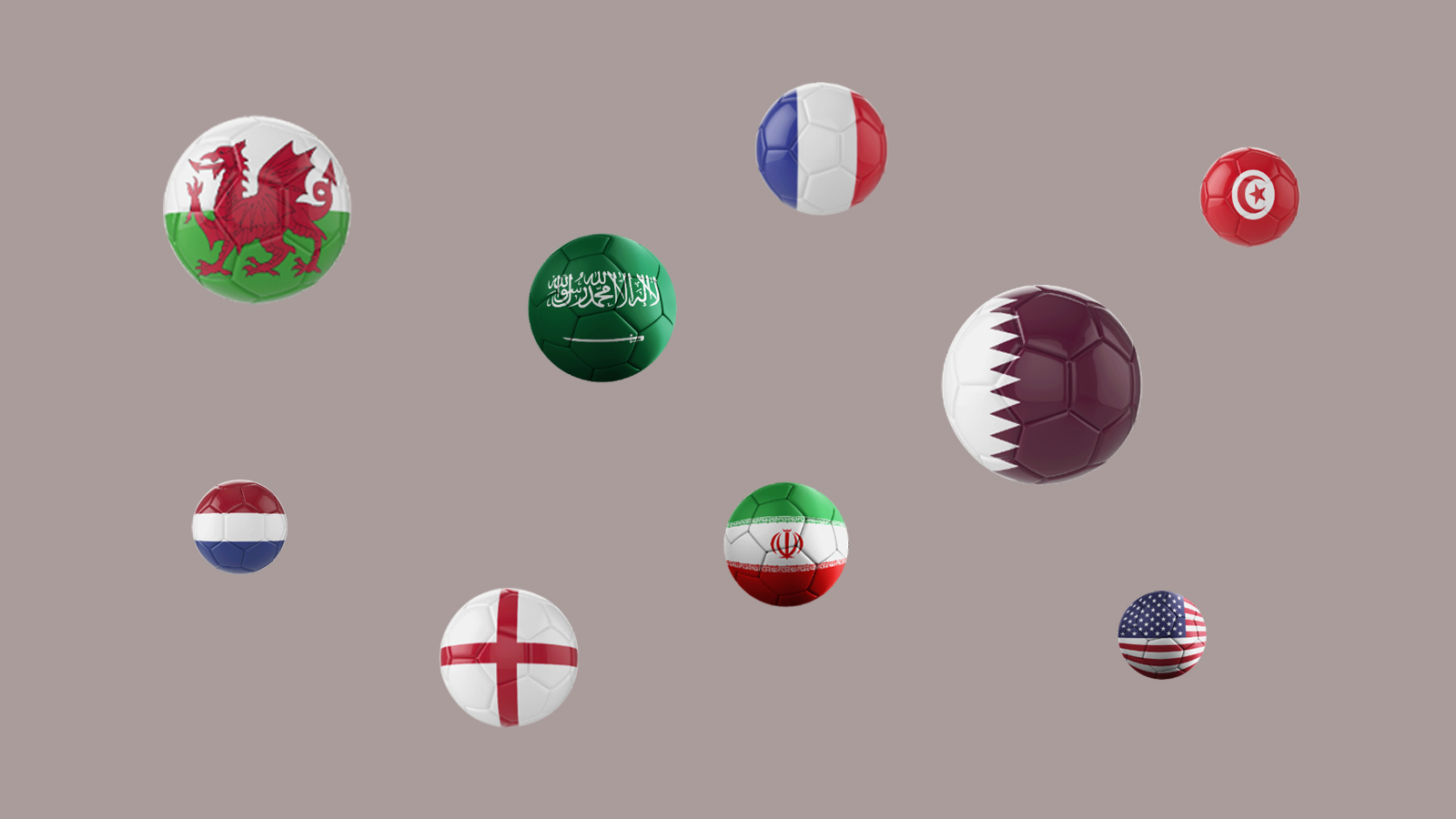

Another big risk to the effectiveness of Mutually Assured Destruction – proliferation of nuclear sides. If North Korea is willing to use its nukes, should South Korea get them? And if Iran gets them, wouldn’t Saudi Arabia follow suit? With a greater number of players, the risks of miscalculations and conflicts of interests grow substantially.

The only way forward, to create a world that cannot be immediately annihilated based on the insecurities and whims of its leaders, is to push for compete nuclear disarmament. Such is the position of the Doomsday clock scientists, who meet every year to determine how close the world is to total annihilation. This year, they set the clock closest to midnight since 1953. The group includes 15 Nobel Prize laureates who are clearly not bullish on the future.