How to disagree well: 7 of the best and worst ways to argue

Many find themselves arguing with someone on the Internet, especially in these days fraught with political tensions. A great tool, the web also seems to drive dispute. It is also a reflection of the larger reality, where divisiveness has spread throughout our society. A classic essay from one of the Internet’s pioneers suggests that there is a way to harness such negative energy of the online world and disagree with people without invoking anger—a lesson that extends far beyond the web.

Paul Graham is an English-born computer programmer with a Ph.D. from Harvard, an accomplished entrepreneur, a VC capitalist as well as a writer. He created the first online store application which he sold to Yahoo and was one of the founders of the famous Y Combinator—a startup incubator that funded over 1,500 startups like Dropbox, Airbnb, Reddit, and Coinbase. Being a true Renaissance man, Graham also studied painting at the Academia di Belle Arti in Florence and the Rhode Island Institute of Design as well as philosophy at Cornell University.

Dubbed “the hacker philosopher” by the tech journalist Steven Levy, Graham has written on a number of subjects on his popular blog at paulgraham.com, which got 34 million pages views in 2015. One of his most lasting contributions has been the now-classic essay ‘How to disagree‘ where he proposed the hierarchy of disagreement which is as relevant today as it was in 2008 when it was first published.

Mark Bui (L) and Donna Saady (R) argue in front of the White House while MoveOn PAC members and supporters marched in protest of the Bush Administration’s handling of the Hurricane Katrina disaster relief September 8, 2005,

in Washington, DC. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)In his essay, Graham proposed that the “web is turning writing into a conversation,” recognizing that the internet has become an unprecedented medium of communication. In particular, it allows people to respond to others in comment threads, on forums and the like. And when we respond on the web, we tend to disagree, concluded Graham.

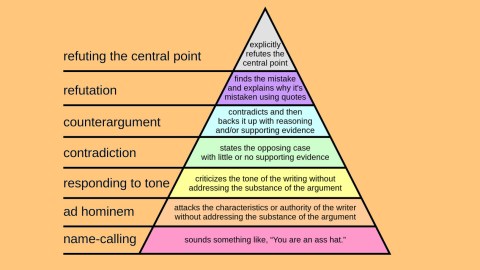

He says this tendency towards disagreement is structurally built into the online experience because in disagreeing, people tend to have much more to say than if they just expressed that they agreed. Interestingly, Graham points out that, even though it might feel like it if you spend much time in comment sections, the world is not necessarily getting angrier. But it could if we don’t observe a certain restraint in how we disagree. To disagree better, which will lead to better conversations and happier outcomes, Graham came up with these seven levels of a disagreement hierarchy (DH):

DH0. Name-calling

To Graham, this is the lowest level of argument. This is when you call people names. That can be done crudely by saying repulsive things like “u r a fag!!!!!!!!!!” or even more pretentiously (but still to the same effect) like, “The author is a self-important dilettante,” wrote the computer scientist.

DH1. Ad hominem

An argument of this kind attacks the person rather than the point they are making—the literal Latin translation of this phrase is: ‘to the person.’ It involves somehow devaluing a person’s opinion by devaluing the one who is expressing it, without directly addressing what they are saying. “The question is whether the author is correct or not,” pointed out Graham.

John Pope (L) expresses his disagreement with supporters of President Donald Trump near the Mar-a-Lago resort home of President Trump on March 4, 2017, in West Palm Beach, Florida. President Trump spent part of the weekend at the house. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

DH2. Responding to tone.

This is a slightly more evolved form of disagreement when the debate moves away from personal attacks to addressing the content of the argument. The lowest form of responding to writing is disagreeing with the author’s tone, according to Graham. For example, one could point out the “cavalier” or “flippant” attitude with which a writer formulated their opinion. But why does that really matter, especially when judging tone can be quite subjective? Stick to the material, Graham advises: “It matters much more whether the author is wrong or right than what [their] tone is.”

DH3. Contradiction

This is a higher form of addressing the actual meat of the argument. In this form of disagreement, you offer an opposing case but very little evidence. You simply state what you think is true, in contrast to the position of the person you are arguing with. Graham gives this example:

“I can’t believe the author dismisses intelligent design in such a cavalier fashion. Intelligent design is a legitimate scientific theory.”

DH4. Counterargument

This next level sets us up on the path to having more productive disputes. A counterargument is a contradiction with evidence and reasoning. When it’s “aimed squarely at the original argument, it can be convincing,” wrote Graham. But, alas, more often than not, passionate arguments end up having both participants actually arguing about different things. They just don’t see it.

Paul Graham. Credit: Flickr/pragdave

DH5. Refutation

This is the most convincing form of disagreement, argues Graham. But it requires work so people don’t do this as often as they should. In general, the higher you go on the pyramid of disagreement, “the fewer instances you find.”

A good way to refute someone is to quote them back to themselves and pick a hole in that quote to expose a flaw. It’s important to find an actual quote to disagree with—“the smoking gun”—and address that.

DH6. Refuting the central point

This tactic is the “most powerful form of disagreement,” contended Graham. It depends on what you are talking about but largely entails refuting someone’s central point. This is in contrast to refuting only minor points of an argument—a form of “deliberate dishonesty” in a debate. An example of that would be correcting someone’s grammar (which slides you back to DH1 level) or pointing out factual errors in names or numbers. Unless those are crucial details, attacking them only serves to discredit the opponent, not their main idea.

The best way to refute someone is to figure out their central point, or one of them if there are several issues involved.

This is how Graham described “a truly effective refutation”:

The author’s main point seems to be x. As he says:

But this is wrong for the following reasons…

Having these tools in evaluating how we argue with each other can go a long way towards regaining some civility in our discourse by avoiding the unproductive lower forms of disagreement. Whether its trolls of other nations or our own home-grown trolls and confused spirits, the conversation over the Internet leaves a lot to be desired for many Americans. It’s hard not to see it as a social malady.

Graham also viewed his hierarchy as a way to weed out dishonest arguments or “fake news” in modern parlance. Forceful words are just a “defining quality of a demagogue,” he pointed out. By understanding the different forms of their disagreement, “we give critical readers a pin for popping such balloons,” wrote Graham.

Read the full essay here: How to Disagree.